S I Section 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 23: the Early Tracheophytes

Chapter 23 The Early Tracheophytes THE LYCOPHYTES Lycopodium Has a Homosporous Life Cycle Selaginella Has a Heterosporous Life Cycle Heterospory Allows for Greater Parental Investment Isoetes May Be the Only Living Member of the Lepidodendrid Group THE MONILOPHYTES Whisk Ferns Ophioglossalean Ferns Horsetails Marattialean Ferns True Ferns True Fern Sporophytes Typically Have Underground Stems Sexual Reproduction Usually Is Homosporous Fern Have a Variety of Alternative Means of Reproduction Ferns Have Ecological and Economic Importance SUMMARY PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Sporophyte Prominence and Survival on Land PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Coal, Smog, and Forest Decline THE OCCUPATION OF THE LAND PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE The First Tracheophytes Were ENVIRONMENT: Diversity Among the Ferns Rhyniophytes Tracheophytes Became Increasingly Better PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE Adapted to the Terrestrial Environment ENVIRONMENT: Fern Spores Relationships among Early Tracheophytes 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. Tracheophytes, also called vascular plants, possess lignified water-conducting tissue (xylem). Approximately 14,000 species of tracheophytes reproduce by releasing spores and do not make seeds. These are sometimes called seedless vascular plants. Tracheophytes differ from bryophytes in possessing branched sporophytes that are dominant in the life cycle. These sporophytes are more tolerant of life on dry land than those of bryophytes because water movement is controlled by strongly lignified vascular tissue, stomata, and an extensive cuticle. The gametophytes, however still require a seasonally wet habitat, and water outside the plant is essential for the movement of sperm from antheridia to archegonia. 2. The rhyniophytes were the first tracheophytes. They consisted of dichotomously branching axes, lacking roots and leaves. They are all extinct. -

Mitochondrial Genomes of the Early Land Plant Lineage

Dong et al. BMC Genomics (2019) 20:953 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-6365-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Mitochondrial genomes of the early land plant lineage liverworts (Marchantiophyta): conserved genome structure, and ongoing low frequency recombination Shanshan Dong1,2, Chaoxian Zhao1,3, Shouzhou Zhang1, Li Zhang1, Hong Wu2, Huan Liu4, Ruiliang Zhu3, Yu Jia5, Bernard Goffinet6 and Yang Liu1,4* Abstract Background: In contrast to the highly labile mitochondrial (mt) genomes of vascular plants, the architecture and composition of mt genomes within the main lineages of bryophytes appear stable and invariant. The available mt genomes of 18 liverwort accessions representing nine genera and five orders are syntenous except for Gymnomitrion concinnatum whose genome is characterized by two rearrangements. Here, we expanded the number of assembled liverwort mt genomes to 47, broadening the sampling to 31 genera and 10 orders spanning much of the phylogenetic breadth of liverworts to further test whether the evolution of the liverwort mitogenome is overall static. Results: Liverwort mt genomes range in size from 147 Kb in Jungermanniales (clade B) to 185 Kb in Marchantiopsida, mainly due to the size variation of intergenic spacers and number of introns. All newly assembled liverwort mt genomes hold a conserved set of genes, but vary considerably in their intron content. The loss of introns in liverwort mt genomes might be explained by localized retroprocessing events. Liverwort mt genomes are strictly syntenous in genome structure with no structural variant detected in our newly assembled mt genomes. However, by screening the paired-end reads, we do find rare cases of recombination, which means multiple concurrent genome structures may exist in the vegetative tissues of liverworts. -

Ecophysiology of Four Co-Occurring Lycophyte Species: an Investigation of Functional Convergence

Research Article Ecophysiology of four co-occurring lycophyte species: an investigation of functional convergence Jacqlynn Zier, Bryce Belanger, Genevieve Trahan and James E. Watkins* Department of Biology, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY 13346, USA Received: 22 June 2015; Accepted: 7 November 2015; Published: 24 November 2015 Associate Editor: Tim J. Brodribb Citation: Zier J, Belanger B, Trahan G, Watkins JE. 2015. Ecophysiology of four co-occurring lycophyte species: an investigation of functional convergence. AoB PLANTS 7: plv137; doi:10.1093/aobpla/plv137 Abstract. Lycophytes are the most early divergent extant lineage of vascular land plants. The group has a broad global distribution ranging from tundra to tropical forests and can make up an important component of temperate northeast US forests. We know very little about the in situ ecophysiology of this group and apparently no study has eval- uated if lycophytes conform to functional patterns expected by the leaf economics spectrum hypothesis. To determine factors influencing photosynthetic capacity (Amax), we analysed several physiological traits related to photosynthesis to include stomatal, nutrient, vascular traits, and patterns of biomass distribution in four coexisting temperate lycophyte species: Lycopodium clavatum, Spinulum annotinum, Diphasiastrum digitatum and Dendrolycopodium dendroi- deum. We found no difference in maximum photosynthetic rates across species, yet wide variation in other traits. We also found that Amax was not related to leaf nitrogen concentration and is more tied to stomatal conductance, suggestive of a fundamentally different sets of constraints on photosynthesis in these lycophyte taxa compared with ferns and seed plants. These findings complement the hydropassive model of stomatal control in lycophytes and may reflect canaliza- tion of function in this group. -

Functional Gene Losses Occur with Minimal Size Reduction in the Plastid Genome of the Parasitic Liverwort Aneura Mirabilis

Functional Gene Losses Occur with Minimal Size Reduction in the Plastid Genome of the Parasitic Liverwort Aneura mirabilis Norman J. Wickett,* Yan Zhang, S. Kellon Hansen,à Jessie M. Roper,à Jennifer V. Kuehl,§ Sheila A. Plock, Paul G. Wolf,k Claude W. dePamphilis, Jeffrey L. Boore,§ and Bernard Goffinetà *Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut; Department of Biology, Penn State University; àGenome Project Solutions, Hercules, California; §Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute and University of California Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Walnut Creek, California; and kDepartment of Biology, Utah State University Aneura mirabilis is a parasitic liverwort that exploits an existing mycorrhizal association between a basidiomycete and a host tree. This unusual liverwort is the only known parasitic seedless land plant with a completely nonphotosynthetic life history. The complete plastid genome of A. mirabilis was sequenced to examine the effect of its nonphotosynthetic life history on plastid genome content. Using a partial genomic fosmid library approach, the genome was sequenced and shown to be 108,007 bp with a structure typical of green plant plastids. Comparisons were made with the plastid genome of Marchantia polymorpha, the only other liverwort plastid sequence available. All ndh genes are either absent or pseudogenes. Five of 15 psb genes are pseudogenes, as are 2 of 6 psa genes and 2 of 6 pet genes. Pseudogenes of cysA, cysT, ccsA, and ycf3 were also detected. The remaining complement of genes present in M. polymorpha is present in the plastid of A. mirabilis with intact open reading frames. All pseudogenes and gene losses co-occur with losses detected in the plastid of the parasitic angiosperm Epifagus virginiana, though the latter has functional gene losses not found in A. -

Plant Press, Vol. 18, No. 3

Special Symposium Issue continues on page 12 Department of Botany & the U.S. National Herbarium The Plant Press New Series - Vol. 18 - No. 3 July-September 2015 Botany Profile Seed-Free and Loving It: Symposium Celebrates Pteridology By Gary A. Krupnick ern and lycophyte biology was tee Chair, NMNH) presented the 13th José of this plant group. the focus of the 13th Smithsonian Cuatrecasas Medal in Tropical Botany Moran also spoke about the differ- FBotanical Symposium, held 1–4 to Paulo Günter Windisch (see related ences between pteridophytes and seed June 2015 at the National Museum of story on page 12). This prestigious award plants in aspects of biogeography (ferns Natural History (NMNH) and United is presented annually to a scholar who comprise a higher percentage of the States Botanic Garden (USBG) in has contributed total vascular Washington, DC. Also marking the 12th significantly to flora on islands Symposium of the International Orga- advancing the compared to nization of Plant Biosystematists, and field of tropical continents), titled, “Next Generation Pteridology: An botany. Windisch, hybridization International Conference on Lycophyte a retired profes- and polyploidy & Fern Research,” the meeting featured sor from the Universidade Federal do Rio (ferns have higher rates), and anatomy a plenary session on 1 June, plus three Grande do Sul, was commended for his (some ferns have tree-like growth using additional days of focused scientific talks, extensive contributions to the systematics, root mantle or have internal reinforce- workshops, a poster session, a reception, biogeography, and evolution of neotro- ment by sclerenchyma instead of lateral a dinner, and a field trip. -

The Complex Origins of Strigolactone Signalling in Land Plants

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/102715; this version posted January 25, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Article - Discoveries The complex origins of strigolactone signalling in land plants Rohan Bythell-Douglas1, Carl J. Rothfels2, Dennis W.D. Stevenson3, Sean W. Graham4, Gane Ka-Shu Wong5,6,7, David C. Nelson8, Tom Bennett9* 1Section of Structural Biology, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, SW7 2Integrative Biology, 3040 Valley Life Sciences Building, Berkeley CA 94720-3140 3Molecular Systematics, The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 4Department of Botany, 6270 University Boulevard, Vancouver, British Colombia, Canada 5Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 6Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 7BGI-Shenzhen, Beishan Industrial Zone, Yantian District, Shenzhen, China. 8Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521 USA 9School of Biology, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK *corresponding author: Tom Bennett, [email protected] Running title: Evolution of strigolactone signalling 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/102715; this version posted January 25, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. ABSTRACT Strigolactones (SLs) are a class of plant hormones that control many aspects of plant growth. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

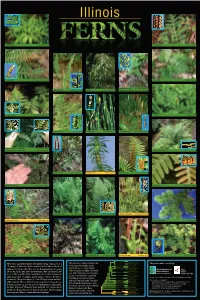

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Dinosaur-Plant Interactions Within a Middle Jurassic Ecosystem—Palynology of the Burniston Bay Dinosaur Footprint Locality, Yorkshire, UK

Palaeobio Palaeoenv (2018) 98:139–151 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-017-0309-9 ORIGINAL PAPER Dinosaur-plant interactions within a Middle Jurassic ecosystem—palynology of the Burniston Bay dinosaur footprint locality, Yorkshire, UK Sam M. Slater1,2 & Charles H. Wellman2 & Michael Romano3 & Vivi Vajda 1 Received: 3 July 2017 /Revised: 18 September 2017 /Accepted: 25 October 2017 /Published online: 20 December 2017 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Dinosaur footprints are abundant in the Middle dominated by Araucariacites australis (probably produced by Jurassic Ravenscar Group of North Yorkshire, UK. Footprints Brachyphyllum mamillare), Perinopollenites elatoides and are particularly common within the Bathonian Long Nab Classopollis spp., with additional bisaccate pollen taxa. Member of the Scalby Formation and more so within the so- Abundant Ginkgo huttonii in the macroflora suggests that much called ‘Burniston footprint bed’ at Burniston Bay. The of the monosulcate pollen was produced by ginkgoes. The di- Yorkshire Jurassic is also famous for its exceptional plant mac- verse vegetation of the Cleveland Basin presumably represent- rofossil and spore-pollen assemblages. Here we investigate the ed an attractive food source for herbivorous dinosaurs. The spore-pollen record from the dinosaur footprint-bearing succes- dinosaurs probably gathered at the flood plains for fresh-water sions in order to reconstruct the vegetation and assess possible and also used the non-vegetated plains and coastline as path- dinosaur-plant interactions. We also compare the spore-pollen ways. Although assigning specific makers to footprints is diffi- assemblages with the macroflora of the Scalby Ness Plant Bed, cult, it is clear that a range of theropod, ornithopod and sauro- which occurs within the same geological member as the pod dinosaurs inhabited the area. -

Selaginella Genome Adds Piece to Plant Evolutionary Puzzle 5 May 2011, by Brian Wallheimer

Selaginella genome adds piece to plant evolutionary puzzle 5 May 2011, by Brian Wallheimer (May 5) in the journal Science. "This plant is a survivor. It has a really long history and it hasn't really changed much over time. When you burn coal, you're burning the Carboniferous relatives of these plants." Banks said the Selaginella genome, with about 22,300 genes, is relatively small. Scientists also discovered that Selaginella is the only known plant not to have experienced a polyploidy event, in which it creates one or more extra sets of chromosomes. Jody Banks led the effort to sequence the genome of Selaginella also is missing genes known in other Selaginella, seen through a shade screen that allows it plants to control flowering, phase changes from to be grown in greenhouses here. Selaginella is the first juvenile plants to adults and other functions. plant of its kind, a lycophyte, to have its genome sequenced. Credit: Purdue Agricultural Communication "It does these in a totally unknown way," Banks photo/Tom Campbell said. Banks said Selaginella's genome would help scientists understand how its genes give the plant (PhysOrg.com) -- A Purdue University-led some of its unique characteristics. The genome sequencing of the Selaginella moellendorffii also will help them understand how Selaginella and (spikemoss) genome - the first for a non-seed other plants are evolutionarily connected. vascular plant - is expected to give scientists a better understanding of how plants of all kinds evolved over the past 500 million years and could open new doors for the identification of new pharmaceuticals. -

81 Vascular Plant Diversity

f 80 CHAPTER 4 EVOLUTION AND DIVERSITY OF VASCULAR PLANTS UNIT II EVOLUTION AND DIVERSITY OF PLANTS 81 LYCOPODIOPHYTA Gleicheniales Polypodiales LYCOPODIOPSIDA Dipteridaceae (2/Il) Aspleniaceae (1—10/700+) Lycopodiaceae (5/300) Gleicheniaceae (6/125) Blechnaceae (9/200) ISOETOPSIDA Matoniaceae (2/4) Davalliaceae (4—5/65) Isoetaceae (1/200) Schizaeales Dennstaedtiaceae (11/170) Selaginellaceae (1/700) Anemiaceae (1/100+) Dryopteridaceae (40—45/1700) EUPHYLLOPHYTA Lygodiaceae (1/25) Lindsaeaceae (8/200) MONILOPHYTA Schizaeaceae (2/30) Lomariopsidaceae (4/70) EQifiSETOPSIDA Salviniales Oleandraceae (1/40) Equisetaceae (1/15) Marsileaceae (3/75) Onocleaceae (4/5) PSILOTOPSIDA Salviniaceae (2/16) Polypodiaceae (56/1200) Ophioglossaceae (4/55—80) Cyatheales Pteridaceae (50/950) Psilotaceae (2/17) Cibotiaceae (1/11) Saccolomataceae (1/12) MARATTIOPSIDA Culcitaceae (1/2) Tectariaceae (3—15/230) Marattiaceae (6/80) Cyatheaceae (4/600+) Thelypteridaceae (5—30/950) POLYPODIOPSIDA Dicksoniaceae (3/30) Woodsiaceae (15/700) Osmundales Loxomataceae (2/2) central vascular cylinder Osmundaceae (3/20) Metaxyaceae (1/2) SPERMATOPHYTA (See Chapter 5) Hymenophyllales Plagiogyriaceae (1/15) FIGURE 4.9 Anatomy of the root, an apomorphy of the vascular plants. A. Root whole mount. B. Root longitudinal-section. C. Whole Hymenophyllaceae (9/600) Thyrsopteridaceae (1/1) root cross-section. D. Close-up of central vascular cylinder, showing tissues. TABLE 4.1 Taxonomic groups of Tracheophyta, vascular plants (minus those of Spermatophyta, seed plants). Classes, orders, and family names after Smith et al. (2006). Higher groups (traditionally treated as phyla) after Cantino et al. (2007). Families in bold are described in found today in the Selaginellaceae of the lycophytes and all the pericycle or endodermis. Lateral roots penetrate the tis detail. -

Phytochrome Diversity in Green Plants and the Origin of Canonical Plant Phytochromes

ARTICLE Received 25 Feb 2015 | Accepted 19 Jun 2015 | Published 28 Jul 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8852 OPEN Phytochrome diversity in green plants and the origin of canonical plant phytochromes Fay-Wei Li1, Michael Melkonian2, Carl J. Rothfels3, Juan Carlos Villarreal4, Dennis W. Stevenson5, Sean W. Graham6, Gane Ka-Shu Wong7,8,9, Kathleen M. Pryer1 & Sarah Mathews10,w Phytochromes are red/far-red photoreceptors that play essential roles in diverse plant morphogenetic and physiological responses to light. Despite their functional significance, phytochrome diversity and evolution across photosynthetic eukaryotes remain poorly understood. Using newly available transcriptomic and genomic data we show that canonical plant phytochromes originated in a common ancestor of streptophytes (charophyte algae and land plants). Phytochromes in charophyte algae are structurally diverse, including canonical and non-canonical forms, whereas in land plants, phytochrome structure is highly conserved. Liverworts, hornworts and Selaginella apparently possess a single phytochrome, whereas independent gene duplications occurred within mosses, lycopods, ferns and seed plants, leading to diverse phytochrome families in these clades. Surprisingly, the phytochrome portions of algal and land plant neochromes, a chimera of phytochrome and phototropin, appear to share a common origin. Our results reveal novel phytochrome clades and establish the basis for understanding phytochrome functional evolution in land plants and their algal relatives. 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA. 2 Botany Department, Cologne Biocenter, University of Cologne, 50674 Cologne, Germany. 3 University Herbarium and Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, USA. 4 Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH3 5LR, UK. 5 New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York 10458, USA. -

Phenology and Function in Lycopod-Mucoromycotina Symbiosis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.316760; this version posted September 29, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Phenology and function in lycopod-Mucoromycotina symbiosis. 2 3 Grace A. Hoysted1*, Martin I. Bidartondo2,3, Jeffrey G. Duckett4, Silvia Pressel4 and 4 Katie J. Field1 5 6 1Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, S10 7 2TN, UK 8 2Comparative Plant and Fungal Biology, Royal botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, 9 TW9 3DS, UK 10 3Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, London, SW7 2AZ, UK 11 4Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, London, SW7 5BD, UK 12 13 *Corresponding author: 14 Grace A. Hoysted ([email protected]) 15 16 Words: 2338 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.316760; this version posted September 29, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 35 Abstract 36 Lycopodiella inundata is a lycophyte with a complex life cycle. The gametophytes 37 and the juvenile, mature and retreating sporophytes form associations with 38 Mucoromycotina fine root endophyte (MFRE) fungi, being mycoheterotrophic as 39 gametophytes and mutualistic as mature sporophytes. However, the function of the 40 symbiosis across juvenile and retreating sporophyte life stages remains unknown.