Elements of Late Style in Johannes Brahms's Sonata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2019 A master of music recital in clarinet Lucas Randall University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2019 Lucas Randall Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Randall, Lucas, "A master of music recital in clarinet" (2019). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 1005. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/1005 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MASTER OF MUSIC RECITAL IN CLARINET An Abstract of a Recital Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Lucas Randall University of Northern Iowa December, 2019 This Recital Abstract by: Lucas Randall Entitled: A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet has been approved as meeting the recital abstract requirement for the Degree of Master of Music. ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Amanda McCandless, Chair, Recital Committee ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Stephen Galyen, Recital Committee Member ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Ann Bradfield, Recital Committee Member ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Jennifer Waldron, Dean, Graduate College This Recital Performance by: Lucas Randall Entitled: A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet Date of Recital: November 22, 2019 has been approved as meeting the recital requirement for the Degree of Master of Music. -

Vorwort Der Ihm Eigenen Selbstironie – Das Ma Folgenden Johannes Brahms

Vorwort der ihm eigenen Selbstironie – das Ma Folgenden Johannes Brahms. Briefwech- nuskript des ganzen Werks als „Probe“ sel, Bd. XII, hrsg. von Max Kalbeck, Ber bezeichnete und es komplett an Mandy lin 1919, Reprint Tutzing 1974, S. 47 ff.). czewski schickte. Dieser begann mit der Nach der Berliner Uraufführung über Zwar hatte Johannes Brahms (1833 – 97) Partiturabschrift des Quintetts, vermut sandte er ihm am 24. Dezember 1891 im Dezember 1890 seinem Verleger Fritz lich weil Brahms’ damaliger Hauptko zunächst die Partiturabschrift des Quin Simrock angekündigt, mit dem Kompo pist William Kupfer zu dieser Zeit noch tetts als Vorlage für ein geplantes Ar nieren aufhören zu wollen, aber schon mit der Abschrift des Klarinettentrios rangement für Klavier zu vier Händen. bald sollte er nochmals tätig werden. Ein befasst war. Nach Abschluss von Satz I Kurz nach der zweiten Aufführung des wichtiger Impuls dafür ging von dem durch Mandyczewski setzte Kupfer die Klarinettenquintetts in Wien gingen am Klarinettisten der Meininger Hofkapelle Abschrift fort und kopierte die Stim 23. Januar dann auch die abschriftlichen Richard Mühlfeld aus, den Brahms im men, vermutlich schrieb er auch die al Stimmen an Simrock zur Vorbereitung Frühjahr 1891 näher kennen und sehr ternative Solopartie für Viola aus. Wann des Stichs. Vermutlich im Februar 1892 schätzen lernte. Begeistert schwärmte die abschriftlichen Materialien fertigge las der Komponist Druckfahnen von er am 17. März in einem Brief an Clara stellt waren, kann nicht genau festge Partitur und Stimmen Korrektur, denn Schumann, man könne „nicht schöner stellt werden. Spätestens zu den ersten am 25. Februar beklagte er sich brief Klarinette blasen, als es der hiesige Herr Proben der beiden neuen Stücke mit Ri lich darüber, dass die Stimmen bereits Mühlfeld tut“. -

A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’S Clarinet Sonata

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata Kenneth T. Aoki Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Composition Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation Aoki, Kenneth T., "A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1077. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1077 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SONATA WITH AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF A BRAHMS' AND HINDEMITH'S CLARINET SONATA A Covering Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Education by Kenneth T. Aoki August, 1968 :N01!83 i iuJ :JV133dS q g re. 'H/ £"Ille; arr THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CENTRAL WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGE presents in KENNETH T. AOKI, Clarinet MRS. PATRICIA SMITH, Accompanist PROGRAM Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in B flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2. J. Brahms Allegro amabile Allegro appassionato Andante con moto II Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano .............................................. 8. Heiden Con moto Andante Vivace, ma non troppo Caprice for B flat Clarinet ................................................... -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Brahms Clarinet Quintet & Trio 6 Songs

martin fröst brahms clarinet quintet & trio 6 songs janine jansen boris brovtsyn maxim rysanov torleif thedéen boris brovtsyn | martin fröst | janine jansen | maxim rysanov | torleif thedéen roland pöntinen BIS-2063 BIS-2063_f-b.indd 1 2014-02-24 14.39 BRAHMS, Johannes (1833–97) Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115 37'46 1 I. Allegro 12'37 2 II. Adagio – Più lento 11'08 3 III. Andantino – Presto non assai, ma con sentimento 4'34 4 IV. Con moto 9'05 Janine Jansen & Boris Brovtsyn violins Maxim Rysanov viola · Torleif Thedéen cello Six Songs, transcribed by Martin Fröst for clarinet and piano 5 Die Mainacht, Op. 43 No. 2 3'32 6 Mädchenlied, Op. 107 No. 5 1'31 7 Immer leiser wird mein Schlummer, Op. 105 No. 2 3'12 8 Wie Melodien zieht es mir, Op. 105 No. 1 2'09 9 Vergebliches Ständchen, Op. 84 No. 4 1'31 10 Feldeinsamkeit, Op. 86 No. 2 3'22 Roland Pöntinen piano 2 Trio in A minor for Clarinet, Piano and Cello 24'33 Op. 114 11 I. Allegro 7'48 12 II. Adagio 7'39 13 III. Andantino grazioso 4'24 14 IV. Allegro 4'25 Roland Pöntinen piano · Torleif Thedéen cello TT: 78'55 Martin Fröst clarinet 3 n the same way that the world owes Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto, Trio and Quintet to the virtuosity of Anton Stadler, and Weber’s clarinet works to IHeinrich Baermann, so the creation of Brahms’s last four chamber works was sparked by the artistry of Richard Mühlfeld (1856–1907), the principal clarinettist of the Meiningen Orchestra. -

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices Valid Until Friday 25 October 2019 Unless Stated Otherwise

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices valid until Friday 25 October 2019 unless stated otherwise ‘The lover with the rose in his hand’ from Le Roman de la 0115 982 7500 Rose (French School, c.1480), used as the cover for The Orlando Consort’s new recording of music by Machaut, entitled ‘The single rose’ (Hyperion CDA 68277). [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, As summer gives way to autumn (for those of us in the northern hemisphere at least), the record labels start rolling out their big guns in the run-up to the festive season. This year is no exception, with some notable high-profile issues: the complete Tchaikovsky Project from the Czech Philharmonic under Semyon Bychkov, and Richard Strauss tone poems from Chailly in Lucerne (both on Decca); the Beethoven Piano Concertos from Jan Lisiecki, and Mozart Piano Trios from Barenboim (both on DG). The independent labels, too, have some particularly strong releases this month, with Chandos discs including Bartók's Bluebeard’s Castle from Edward Gardner in Bergen, and the keenly awaited second volume of British tone poems under Rumon Gamba. Meanwhile Hyperion bring out another volume (no.79!) of their Romantic Piano Concerto series, more Machaut from the wonderful Orlando Consort (see our cover picture), and Brahms songs from soprano Harriet Burns. Another Hyperion Brahms release features as our 'Disc of the Month': the Violin Sonatas in a superb new recording from star team Alina Ibragimova and Cédric Tiberghien (see below). -

May 2018 List

May 2018 Catalogue Issue 25 Prices valid until Wednesday 27 June 2018 unless stated otherwise 0115 982 7500 [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, Glorious sunshine and summer temperatures prevail as this foreword is being written, but we suspect it will all be over by the time you are reading it! On the plus side, at least that means we might be able to tempt you into investing in a little more listening material before the outside weather arrives for real… We were pleasantly surprised by the number of new releases appearing late April and into May, as you may be able to tell by the slightly-longer-than-usual new release portion of this catalogue. Warner & Erato certainly have plenty to offer us, taking up a page and half of the ‘priorities’ with new recordings from Nigel Kennedy, Philippe Jaroussky, Emmanuel Pahud, David Aaron Carpenter and others, alongside some superbly compiled boxsets including a Massenet Opera Collection, performances from Joseph Keilberth (in the ICON series), and two interesting looking Debussy collections: ‘Centenary Discoveries’ and ‘His First Performers’. Rachel Podger revisits Vivaldi’s Four Seasons for Channel Classics (already garnering strong reviews), Hyperion offer us five new titles including Schubert from Marc-Andre Hamelin and Berlioz from Lawrence Power and Andrew Manze (see ‘Disc of the Month’ below), plus we have strong releases from Sandrine Piau (Alpha), the Belcea Quartet joined by Piotr Anderszewski (also Alpha), Magdalena Kozena (Supraphon), Osmo Vanska (BIS), Boris Giltberg (Naxos) and Paul McCreesh (Signum). -

Prominent Schools of Clarinet Sound (National Styles)

Prominent Schools of Clarinet Sound (National Styles) German School (Oehler system, up to 27 keys) Description: dark, compact, well in tune but difficult to play very softly Players: Karl Leister, Sabine Meyer French School (Boehm system, 16 or 17 keys) Description: clear, bright/too bright, large dynamic range Players: Anthony Gigliotti, Phillippe Cuper Italian School (Boehm system) Description: voice-like quality Opera tradition Players: Ernesto Cavallini, Alessandro Carbonare American School (Boehm system) Description: Strong French influence but more open and wide, more air and flexibility Connections to jazz and film music Players: Larry Combs, Richard Stolzman, Charles Neidich, Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw JDG 20200815 The Most-used Types of Clarinets Band Eb Clarinet Bb Clarinet***** Eb Alto Clarinet Bb Bass Clarinet Eb Contra Alto Clarinet Bb Contra Bass Clarinet Orchestra Eb Clarinet C Clarinet Bb Clarinet A Clarinet Bb Bass Clarinet Worth Mentioning Basset Horn (in F) Basset Clarinet (in A) When an instrument plays its C and that sound/pitch is the same as the piano’s C, we say the instrument is “in C” When an instrument plays its C and that sound/pitch is the same as the piano’s Bb, we say the instrument is “in Bb” When an instrument plays its C and that sound/pitch is the same as the piano’s Eb, we say the instrument is “in Eb” And so on. JDG 20200815 Equipment Clarinets Rubber/plastic/ebonite, wood, carbon composites • Buffet • Selmer • LeBlanc • Yamaha • Bundy Mouthpieces Rubber, glass (metal) • Vandoren • Selmer • Yamaha • LeBlanc Reeds Cane or synthetic • Vandoren • Rico • Alexander • Gonzalez Ligatures and mouthpiece caps • Vandoren • Bonade (inverted) • LeBlanc • Rovner • Unnamed Tips • I purchase new instruments and used instruments. -

Solo List and Reccomended List for 02-03-04 Ver 3

Please read this before using this recommended guide! The following pages are being uploaded to the OSSAA webpage STRICTLY AS A GUIDE TO SOLO AND ENSEMBLE LITERATURE. In 1999 there was a desire to have a required list of solo and ensemble literature, similar to the PML that large groups are required to perform. Many hours were spent creating the following document to provide “graded lists” of literature for every instrument and voice part. The theory was a student who made a superior rating on a solo would be required to move up the list the next year, to a more challenging solo. After 2 years of debating the issue, the music advisory committee voted NOT to continue with the solo/ensemble required list because there was simply too much music written to confine a person to perform from such a limited list. In 2001 the music advisor committee voted NOT to proceed with the required list, but rather use it as “Recommended Literature” for each instrument or voice part. Any reference to “required lists” or “no exceptions” in this document need to be ignored, as it has not been updated since 2001. If you have any questions as to the rules and regulations governing solo and ensemble events, please refer back to the OSSAA Rules and Regulation Manual for the current year, or contact the music administrator at the OSSAA. 105 SOLO ENSEMBLE REGULATIONS 1. Pianos - It is recommended that you use digital pianos when accoustic pianos are not available or if it is most cost effective to use a digital piano. -

02 October 2020

02 October 2020 12:01 AM Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) Early one morning for voice and piano Elizabeth Watts (soprano), Paul Turner (piano) GBBBC 12:05 AM Juan Crisostomo Arriaga (1806-1826) Los Esclavos Felices - overture Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Juanjo Mena (conductor) NONRK 12:12 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Variations on "Deandl is arb auf mi'" for string trio Leopold String Trio GBBBC 12:19 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Double Concerto in C minor, BWV 1060 Hans-Peter Westermann (oboe), Mary Utiger (violin), Camerata Koln DEWDR 12:33 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Fugue (BWV.542) 'Great' (orig. for organ) Guitar Trek AUABC 12:40 AM Isaac Albeniz (1860-1909) Suite espanola , Op 47 Ilze Graubina (piano) LVLR 01:02 AM Eugen Suchon (1908-1993) The Night of the Witches, symphonic poem Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mario Kosik (conductor) SKSR 01:22 AM Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921) Clarinet Sonata in E flat, Op 167 Annelien Van Wauwe (clarinet), Simon Lepper (piano) GBBBC 01:39 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Nisi Dominus (Psalm 127) for voice and orchestra (RV.608) Matthew White (counter tenor), Arte dei Suonatori, Eduardo Lopez Banzo (conductor) PLPR 02:01 AM Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936),Anatoly Lyadov (1855-1914),Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840- 1893) Fugue in D minor; Sarabande in D minor; Polka in D; Excerpts from 'The Seasons' Maria Wloszczowska (violin), Joseph Puglia (violin), Timothy Ridout (viola), Xenia Jankovic (cello), Alasdair Beatson (piano) CHSRF 02:26 AM Igor Stravinsky (1882 - 1971) Divertimento -

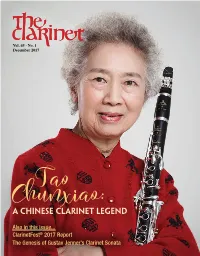

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

School of Music 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Music 2016–2017 School of Music 2016–2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Goff-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849.