INTERSECTIONALITY UNDONE Saving Intersectionality from Feminist Intersectionality Studies 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONCEPTUALIZING RACIAL DISPARITIES in HEALTH Advancement of a Socio-Psychobiological Approach

CONCEPTUALIZING RACIAL DISPARITIES IN HEALTH Advancement of a Socio-Psychobiological Approach David H. Chae Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University Amani M. Nuru-Jeter School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley Karen D. Lincoln School of Social Work, University of Southern California Darlene D. Francis School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley Abstract Although racial disparities in health have been documented both historically and in more contemporary contexts, the frameworks used to explain these patterns have varied, ranging from earlier theories regarding innate racial differences in biological vulnerability, to more recent theories focusing on the impact of social inequalities. However, despite increasing evidence for the lack of a genetic definition of race, biological explanations for the association between race and health continue in public health and medical discourse. Indeed, there is considerable debate between those adopting a “social determinants” perspective of race and health and those focusing on more individual-level psychological, behavioral, and biologic risk factors. While there are a number of scientifically plausible and evolving reasons for the association between race and health, ranging from broader social forces to factors at the cellular level, in this essay we argue for the need for more transdisciplinary approaches that specify determinants at multiple ecological levels of analysis. We posit that contrasting ways of examining race and health are not necessarily incompatible, and that more productive discussions should explicitly differentiate between determinants of individual health from those of population health; and between inquiries addressing racial patterns in health from those seeking to explain racial disparities in health. Specifically, we advance a socio-psychobiological framework, which is both historically grounded and evidence-based. -

W. E. B. Du Bois at the Center: from Science, Civil Rights Movement, to Black Lives Matter

The British Journal of Sociology 2017 Volume 68 Issue 1 W. E. B. Du Bois at the center: from science, civil rights movement, to Black Lives Matter Aldon Morris Abstract I am honoured to present the 2016 British Journal of Sociology Annual Lecture at the London School of Economics. My lecture is based on ideas derived from my new book, The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology. In this essay I make three arguments. First, W.E.B. Du Bois and his Atlanta School of Sociology pioneered scientific sociology in the United States. Second, Du Bois pioneered a public sociology that creatively combined sociology and activism. Finally, Du Bois pioneered a politically engaged social science relevant for contemporary political struggles including the contemporary Black Lives Mat- ter movement. Keywords: W. E. B. Du Bois; Atlanta School; scientific sociology; sociological theory; sociological discrimination and marginalization Innovative science of society There is an intriguing, well-kept secret, regarding the founding of scientific soci- ology in America. The first school of American scientific sociology was founded by a black professor located in a small, economically poor, racially segregated black university. At the dawn of the twentieth century – from 1898 to 1910 – the black sociologist, and activist, W.E.B. Du Bois, developed the first scientific school of sociology at a historic black school, Atlanta University. It is a monumental claim to argue Du Bois developed the first scientific school of sociology in America. Indeed, my purpose in writing The Scholar Denied was to shift our understanding of the founding, over a hundred years ago, of one of the social sciences in America. -

Self Study Report

Department of Latina and Latino Studies College of Ethnic Studies Seventh Cycle Program Review – Self Study Report June 2017 Revised August 2017 The enclosed self-study report was submitted for external review on August 25, 2017 and sent to reviewers on October 4th, 2017. Latina/Latino Studies San Francisco State University 7th Cycle Program Review 2017 Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................1 2.0 Overview of the Program ...........................................................................................4 2.1 Latina/Latino Studies (LTNS) Mission Statement ....................................................4 2.2 Educational Value of the Curriculum ........................................................................5 3.0 Program Indicators ......................................................................................................6 3.1 Program Planning: Revisiting Previous Departmental Review .................................6 3.2 Student Learning and Achievement .........................................................................10 3.2a Retention, Completion and Time to Degree ..................................................15 3.2b Results from LTNS Student Surveys .............................................................16 3.3 The Curriculum ....................................................................................................... 37 3.3a Culminating Experience Requirement ......................................................... -

What Is Racial Domination?

STATE OF THE ART WHAT IS RACIAL DOMINATION? Matthew Desmond Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Mustafa Emirbayer Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Abstract When students of race and racism seek direction, they can find no single comprehensive source that provides them with basic analytical guidance or that offers insights into the elementary forms of racial classification and domination. We believe the field would benefit greatly from such a source, and we attempt to offer one here. Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination so that students of the subjects—especially those seeking a general (if economical) introduction to the vast field of race studies—can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective (and fallacious) ways to think about racial domination. Focusing primarily on the American context, we begin by defining race and unpacking our definition. We then describe how our conception of race must be informed by those of ethnicity and nationhood. Next, we identify five fallacies to avoid when thinking about racism. Finally, we discuss the resilience of racial domination, concentrating on how all actors in a society gripped by racism reproduce the conditions of racial domination, as well as on the benefits and drawbacks of approaches that emphasize intersectionality. Keywords: Race, Race Theory, Racial Domination, Inequality, Intersectionality INTRODUCTION Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination, providing in a single essay a source through which thinkers—especially those seeking a general ~if economical! introduction to the vast field of race studies— can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective ways to think about racial domination. -

Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race INSTRUCTIONS for AUTHORS

Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race INSTRUCTIONS FOR AUTHORS EDITOR Aims and Scope Lawrence D. Bobo Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race (DBR) is an innovative periodical that presents and analyzes Harvard University the best cutting-edge research on race from the social sciences. It provides a forum for discussion and increased understanding of race and society from a range of disciplines, including but not limited to economics, political science, sociology, anthropology, law, communications, public policy, psychology, and history. Each issue of SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR DBR opens with remarks from the editors concerning the three subsequent and substantive sections: STATE Tommie Shelby OF THE D ISCIPLINE, where broad-gauge essays and provocative think-pieces appear; STATE OF THE A RT, dedicated Harvard University to observations and analyses of empirical research; and STATE OF THE DISCOURSE, featuring expansive book reviews, special feature essays, and occasionally, debates. For more information about the Du Bois Review ADVISORY BOARD please visit our website at http://hutchinscenter.fas.harvard.edu/du-bois-review or fi nd us on Facebook and Twitter. William Julius Wilson, Chair Manuscript Submission Harvard University DBR is a blind peer-reviewed journal. To be considered for publication in either STATE OF THE A RT or STATE Mahzarin Banaji Evelyn Nakano Glenn Lauren McLaren OF THE DISCIPLINE, an electronic copy of a manuscript (hard copies are not required) should be sent to: Harvard University University of California, Berkeley University of Nottingham Managing Editor, Du Bois Review, Hutchins Center, Harvard University, 104 Mount Auburn Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. -

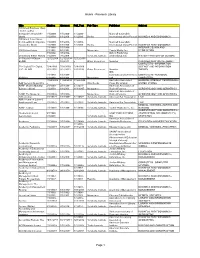

Research Library Page 1

Alumni - Research Library Title Citation Abstract Full_Text Pub Type Publisher Subject 100 Great Business Ideas : from Leading Companies Around the 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 100 Great Sales Ideas : from Leading Companies 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish Around the World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- INTERIOR DESIGN AND 1001 Home Ideas 6/1/1991 6/1/1991 Magazines Family Media, Inc. DECORATION 3/1/2002- 3/1/2002- Oxford Publishing 20 Century British History 7/1/2009 7/1/2009 Scholarly Journals Limited(England) HISTORY--HISTORY OF EUROPE 33 Charts [33 Charts - 12/12/2009 12/12/2009- 12/12/2009 BLOG] + 6/3/2011 + Other Resources Newstex CHILDREN AND YOUTH--ABOUT COMPUTERS--INFORMATION 50+ Digital [50+ Digital, 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- SCIENCE AND INFORMATION LLC - BLOG] 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 Other Resources Newstex THEORY IDG 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- Communications/Peterboro COMPUTERS--PERSONAL 80 Micro 6/1/1988 6/1/1988 Magazines ugh COMPUTERS 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 Australian Associated GENERAL INTEREST PERIODICALS-- AAP General News Wire + + + Wire Feeds Press Pty Limited UNITED STATES AARP Modern Maturity; 2/1/1988- 2/1/1988- 2/1/1991- American Association of [Library edition] 1/1/2003 1/1/2003 11/1/1997 Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS American Association of AARP The Magazine 3/1/2003+ 3/1/2003+ Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS ABA Journal 8/1/1972+ 1/1/1988+ 1/1/1992+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW ABA Journal of Labor & Employment Law 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW MEDICAL SCIENCES--NURSES AND ABNF Journal 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ Scholarly Journals Tucker Publications, Inc. -

Theory and Racialized Modernity: Du Bois in Ascendance

EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION Theory and Racialized Modernity Du Bois in Ascendance Lawrence D. Bobo Department of African and African American Studies and Department of Sociology , Harvard University The United States is neither done with race nor with the problem of racism. In this dilemma the U.S. is not alone. In Brazil and much of the rest of Latin America active pigmentocracies still relegate those of African descent and darker skinned indigenous peoples to the lower rungs of society (Gates 2011 ; Gudmunson and Wolfe, 2010 ; Hooker 2009 ; Joseph 2015 ; Telles 2014 ). Despite a great multiracial democratic revo- lution and the rise of numerous Black Africans into its economic elite, South Africa is far from done with the deep wounds and legacies of ongoing, vast Black poverty and economic marginalization attendant to its apartheid past (Gibson 2015 ; Nattrass and Seekings, 2001 ; Seekings 2008 ). Where it was once erected, although subject to much complexity and change in the modern era, the color line endures almost anywhere one looks around the globe. The notion of modernity we typically associate with two intersecting streams of ideas. One of these streams involves ideals of economic growth and development, free markets, and technological innovation. The other stream involves ideals of freedom, egalitarianism, and democracy. With the march forward of these intersecting streams much social thought foretold the withering of old ascriptive inequalities and barriers tied to racial and ethnic distinctions. But as ethnic studies scholar Elisa Joy White ( 2012 ) has put it, such “contemporary renderings of modernity are intrinsically flawed because of the structural antecedent of race-based social inequality” (p. -

Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race Instructions for Authors

Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race Instructions for Authors Aims and Scope Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race (DBR) is an innovative periodical that presents and analyzes the best cutting-edge research on race from the social sciences. It provides a forum for discussion and increased understanding of race and society from a range of disciplines, including but not limited to economics, political science, sociology, anthropology, law, communications, public policy, psychology, and history. Each issue of DBR opens with remarks from the editors concerning the three subsequent and substantive sections: STATE OF THE DISCIPLINE, where broad-gauge essays and provocative think-pieces appear; STATE OF THE ART, dedicated to observations and analyses of empirical research; and STATE OF THE DISCOURSE, featuring expansive book reviews, special feature essays, and occasionally, debates. Manuscript Submission DBR is a double blind peer-reviewed journal. To be considered for publication in either STATE OF THE ART or STATE OF THE DISCIPLINE, please send an electronic copy of your manuscript (with self-references removed except for those on a separable title page) to [email protected]. In STATE OF THE DISCOURSE, the Du Bois Review publishes substantive (5-10,000 word) review essays of multiple (three or four) thematically related books. Proposals for review essays should be directed to the Managing Editor at [email protected]. Manuscript Originality The Du Bois Review publishes only original, previously unpublished (whether hard copy or electronic) work. Submitted manuscripts may not be under review for publication elsewhere while under consideration at DBR. Papers with multiple authors are reviewed under the assumption that all authors have approved the submitted manuscript and concur with its submission to the DBR. -

WEB Du Bois and Interdisciplinarity

JCS0010.1177/1468795X20938624Journal of Classical SociologyBesek et al. 938624research-article2020 Article Journal of Classical Sociology 1 –21 W.E.B. Du Bois and © The Author(s) 2020 Article reuse guidelines: interdisciplinarity: A sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X20938624DOI: 10.1177/1468795X20938624 comprehensive picture journals.sagepub.com/home/jcs of the scholar’s approach to natural science Jordan Fox Besek State University of New York at Buffalo, USA Patrick Trent Greiner Vanderbilt University, USA Brett Clark The University of Utah, USA Abstract Throughout his life, W.E.B. Du Bois actively engaged the scientific racism infecting natural sciences and popular thought. Nevertheless, he also demonstrated a sophisticated and critical engagement with natural science. He recognized that the sciences were socially situated, but also that they addressed real questions and issues. Debate remains, however, regarding exactly how and why Du Bois incorporated such natural scientific knowledge into his own thinking. In this article, we draw on archival research and Du Bois’ own scholarship to investigate his general approach to interdisciplinarity. We address how and why he fused natural scientific knowledge and the influence of physical environs into his social science, intertwining each with his broader intellectual and political aims. This investigation will offer a fuller understanding of the scope and aims of his empirical scholarship. At the same time, it will illuminate a sociological approach to natural science that can still inform scholarship today. Keywords Dilthey, Du Bois, environmental sociology, interdisciplinarity, scientific racism Corresponding author: Jordan Fox Besek, Department of Sociology, State University of New York at Buffalo, 430 Park Hall, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA. -

Necrolinguistics: the Linguistically Stranded1

Necrolinguistics: The Linguistically Stranded1 John Mugane Harvard University 1. Introduction What is happening to African languages? As in all natural life, languages either evolve or die. Languages evolve because new and different forms develop in small increments, which accumulate over time to bring about significant changes. Language demise can be sudden, especially with natural disasters such as earthquakes and floods, which wipe out entire ethnolinguistic communities, but it is often gradual. The decimation of language does not always mean that its people cease to exist, but rather that people carry on with adopted languages. Languages may vanish leaving behind linguistically stranded populations, who may be described as “discordant monolinguals” and “semi- lingual folk.” Language shift is not a neat process by which populations blissfully commute from one language to another; rather, it is a process that is fraught with untold problems and difficulties. This paper discusses the linguistic estrangement of East Africans (and by extension, sub-Saharan Africans) as an epiphenomenon of language shift. 2. The linguistically stranded Linguistic strandedness is characterized by those who speak only one language, but are socialized in the culture of another. This strandedness sometimes takes two forms. The first—linguistic monoligualism—means that nowadays we can talk about a Swahili monolingual Mchagga (Chagga person), an English monolingual Mugikuyu (Kikuyu of Kenya), a French monolingual Mukoongo (Democratic Republic of the Congo), and a Portuguese monolingual Makhuwa (Mozambique). Being linguistically stranded in this manner leaves one with a double consciousness as described by the scholar W. E. B. Du Bois (in The Souls of Black Folk) such that a person belongs to a particular culture yet the language they speak is that of another. -

Radical Cosmopolitanism: W.E.B. Du Bois, Germany, and African American Pragmatist Visions for TwentyFirst Century Europe

GÜNTER H. LENZ Radical Cosmopolitanism: W.E.B. Du Bois, Germany, and African American Pragmatist Visions for TwentyFirst Century Europe Introduction At the centennial of the publication of W.E.B. Du Bois’s most famous book, The Souls of Black Folk (1903), we asked the questions: What has been its influence? What does or can it mean today at the beginning of the new century, in a time of globalization, relocalizations, and Violent conflicts among nations, religions, ethnic and racial groups, a time of postcolonialism and new manifestations of imperialism, in a time of postmodernism, a radical critique of the enlightenment tradition, and the powerful manifesta tions of minority and border discourses? It is wellknown that Germany played an important role in Du Bois’s intellectual deVelopment and that he traVelled to Germany seVeral times over more than six decades. He wrote about his Very different experiences in the country and the intellectual and cultural influences he took up, appropriated, and transformed for his own purposes. He discussed the multiple genres and kinds of discourses he used and deVeloped in order to come to terms with the Various conflicting strains and modes in German culture and society in his many books and countless articles. Yet his work has remained Virtually unknown to the Germanspeaking public outside academia. During the second half of the 1960s his Autobiography was published in a German translation, or, better, edited Version, in the German Democratic Republic, Mein Weg, meine Welt (trans. Erich Salewski, preface Jürgen Kuczynski, 1969). And, interestingly enough, The Souls of Black Folk was finally published in 2003 as Die Seelen der Schwarzen in a German translation by Jürgen MeyerWendt by Orange Press, Freiburg, with a preface by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. -

Empirical Study of the Application of Double-Consciousness Among African-American Men

Journal of African American Studies (2018) 22:205–217 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-018-9404-x ARTICLES Empirical Study of the Application of Double-Consciousness Among African-American Men Sheena Myong Walker1 Published online: 11 August 2018 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract The current study serves to add to the existing literature on African-American men and masculinity, and to provide empirical evidence of the hypothesized mental conflict that exists among African-Americans, particularly as it relates to double-consciousness. Mental conflict was measured as a function of psychological distress, surfacing in high levels of depression, anxiety, and somatization, made evident through the measurement of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18). It was hypothesized that African- American men engaged in the practice of double-consciousness made evident through the scores on the General Ethnicity Questionnaire (GEQ). More specifically, those who failed to integrate and only identified with one’s Blackness and those who made drastic changes in one’s reality by taking on characteristics of the Eurocentric worldview were expected to have higher levels of psychological distress. Results from this study found a practical use of the theory of double-consciousness and further provide implications for future research on the topic. Keywords Double-consciousness . African-American masculinity. Multiple identities . Intersection Introduction The present study addressed the psychological impact that occurs among African- American men as a result of the engagement in double-consciousness. W.E.B. Du Bois (1982) theorized that personalities of cultural minorities could not develop without creating a deep Binternal division,^ defined as a fundamental rift that is created solely by membership in a group that has been socially defined as inferior (Du Bois 1982; * Sheena Myong Walker [email protected] 1 University of the Virgin Islands, St.