WEB Du Bois and the Dismal Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONCEPTUALIZING RACIAL DISPARITIES in HEALTH Advancement of a Socio-Psychobiological Approach

CONCEPTUALIZING RACIAL DISPARITIES IN HEALTH Advancement of a Socio-Psychobiological Approach David H. Chae Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University Amani M. Nuru-Jeter School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley Karen D. Lincoln School of Social Work, University of Southern California Darlene D. Francis School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley Abstract Although racial disparities in health have been documented both historically and in more contemporary contexts, the frameworks used to explain these patterns have varied, ranging from earlier theories regarding innate racial differences in biological vulnerability, to more recent theories focusing on the impact of social inequalities. However, despite increasing evidence for the lack of a genetic definition of race, biological explanations for the association between race and health continue in public health and medical discourse. Indeed, there is considerable debate between those adopting a “social determinants” perspective of race and health and those focusing on more individual-level psychological, behavioral, and biologic risk factors. While there are a number of scientifically plausible and evolving reasons for the association between race and health, ranging from broader social forces to factors at the cellular level, in this essay we argue for the need for more transdisciplinary approaches that specify determinants at multiple ecological levels of analysis. We posit that contrasting ways of examining race and health are not necessarily incompatible, and that more productive discussions should explicitly differentiate between determinants of individual health from those of population health; and between inquiries addressing racial patterns in health from those seeking to explain racial disparities in health. Specifically, we advance a socio-psychobiological framework, which is both historically grounded and evidence-based. -

Download Original 3.01 MB

Smw apgro^. CONTENTS FOR JANUARY, 1893. Transition in the Industrial Status of Woman . Katharine Coman 171 The Novel of the Future Alice W. Kellogg 178 A Night in the Cathedral Mary E. Dillingham 182 At Sunset Edith E. Tuxbury 184 Themes 184 Norse Fiction Martha G. McCaulley 188 The Dark Florence Converse. 193 Sketches Involving Prorlems.—A Settlement Study Caroline L. Williamson 193 Editorial 199 Free Press 204 Book Reviews 209 Exchanges 212 College Notes 217 Society Notes 217 College Bulletin 218 Alumnae Notes 219 Mabkiagks, Bibths, Deaths 220 Entered in the Post-oiiice at Wellesley, Mass., as second-class matter. tuno rftiNTina comfaky, «03icm. L. P. Hollander & Co., kadies' Jackets, Goats, Ulsters mi JSafitles. The Largest Assortment of Fine Goods in the Country. Our Selections for Fall and Winter comprise every variety of garments. Our chief aim has been to secure exclusive shapes and materials, and as few duplicates as possible. Our prices we guarantee to be as low as any in the city for similar qualities. ll&Aids ^ fpinpnjed MISh The Latest Parisian Shapes and Novelties in Trimmings. Also ENGLISH ROUND HATS, From Henry Heath of London. 202 Boylston Street, and Park Square, Boston, Also 290 Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK. GENUINE ZRTXSIHITOISPS Light Cedar Boats and Canoes. EASY ROWING. SROES r ^?T~ -~r^ of evepg description. The latest in style, best in quality, at moderate prices. Gymnasium shoes of all kinds at low prices. Special discount to Wcllesley Students and Teachers. Tennis Goods, Racquets, etc. Skates, Dumb Bells, Indian Clubs. Fine French Opera Glasses. Leather Dogskin Walking and Exercising Jackets, for both ladies and gentlemen, soft as kid, used in riding, skating, etc.; impervious to cold. -

Right-Wing Congressman Mo Brooks Quotes Socialist Lesbian Poet to Justify His Opposition to Immigration Reform

June 13, 2014 Right-wing Congressman Mo Brooks Quotes Socialist Lesbian Poet to Justify His Opposition to Immigration Reform Posted: 07/14/2013 5:00 pm On Wednesday, Republican Congressman Mo Brooks of Alabama used the words of a lesbian socialist poet to oppose immigration reform. House Speaker John Boehner organized the meeting of the Republican caucus in the basement of the Capital building to discuss how his party would respond to the Senate's proposal to overhaul the nation's immigration laws. During the emotional two-and-a-half hour gathering, Republican members lined up 10 deep at two microphones to weigh in on the unfolding controversy, according to the New York Times. When it was his turn to grab the microphone, Brooks read a line from "America the Beautiful" to make his point that respect for the rule of law must be inviolable: "Confirm thy soul in self control, thy liberty in law," Brooks said. Brooks explained that he used these lines to remind his GOP colleagues that he will strongly oppose any proposal "that rewards or ratifies illegal conduct. Anyone who's come to our country whose first step on American soil is to thumb their nose at American law and violate our law, we should not reward them with our highest honor, which is citizenship," the Washington Post reported. Brooks' official biography on his Congressional website does not indicate that he's a lover of poetry or a student of American social history. So perhaps we wasn't aware that "America the Beautiful" was written by Katherine Lee Bates, who was a Christian socialist, a lesbian, and an ardent foe of American imperialism. -

Coman's “Some Unsettled Problems of Irrigation”

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INSTITUTIONAL PATH DEPENDENCE IN CLIMATE ADAPTATION: COMAN'S “SOME UNSETTLED PROBLEMS OF IRRIGATION” Gary D. Libecap Working Paper 16324 http://www.nber.org/papers/w16324 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2010 Helpful comments and suggestions were provided by Zack Donohew, Eric Edwards, P.J. Hill, Charles W. Howe, Mark Kanazawa, Clay Landry, Dean Lueck, Robert Moffitt, Trevor O’Grady, and Henry Smith. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by Gary D. Libecap. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Institutional Path Dependence in Climate Adaptation: Coman’s “Some Unsettled Problems of Irrigation” Gary D. Libecap NBER Working Paper No. 16324 September 2010 JEL No. N51,N52,Q15,Q25,Q54 ABSTRACT Katharine Coman’s “Some Unsettled Problems of Irrigation,” published in March 1911 in the first issue of the American Economic Review addressed issues of water supply, rights, and organization. These same issues have relevance today 100 years later in face of growing concern about the availability of fresh water worldwide as demand grows and as supplies become more uncertain due to the potential effects of climate change. -

W. E. B. Du Bois at the Center: from Science, Civil Rights Movement, to Black Lives Matter

The British Journal of Sociology 2017 Volume 68 Issue 1 W. E. B. Du Bois at the center: from science, civil rights movement, to Black Lives Matter Aldon Morris Abstract I am honoured to present the 2016 British Journal of Sociology Annual Lecture at the London School of Economics. My lecture is based on ideas derived from my new book, The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology. In this essay I make three arguments. First, W.E.B. Du Bois and his Atlanta School of Sociology pioneered scientific sociology in the United States. Second, Du Bois pioneered a public sociology that creatively combined sociology and activism. Finally, Du Bois pioneered a politically engaged social science relevant for contemporary political struggles including the contemporary Black Lives Mat- ter movement. Keywords: W. E. B. Du Bois; Atlanta School; scientific sociology; sociological theory; sociological discrimination and marginalization Innovative science of society There is an intriguing, well-kept secret, regarding the founding of scientific soci- ology in America. The first school of American scientific sociology was founded by a black professor located in a small, economically poor, racially segregated black university. At the dawn of the twentieth century – from 1898 to 1910 – the black sociologist, and activist, W.E.B. Du Bois, developed the first scientific school of sociology at a historic black school, Atlanta University. It is a monumental claim to argue Du Bois developed the first scientific school of sociology in America. Indeed, my purpose in writing The Scholar Denied was to shift our understanding of the founding, over a hundred years ago, of one of the social sciences in America. -

Self Study Report

Department of Latina and Latino Studies College of Ethnic Studies Seventh Cycle Program Review – Self Study Report June 2017 Revised August 2017 The enclosed self-study report was submitted for external review on August 25, 2017 and sent to reviewers on October 4th, 2017. Latina/Latino Studies San Francisco State University 7th Cycle Program Review 2017 Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................1 2.0 Overview of the Program ...........................................................................................4 2.1 Latina/Latino Studies (LTNS) Mission Statement ....................................................4 2.2 Educational Value of the Curriculum ........................................................................5 3.0 Program Indicators ......................................................................................................6 3.1 Program Planning: Revisiting Previous Departmental Review .................................6 3.2 Student Learning and Achievement .........................................................................10 3.2a Retention, Completion and Time to Degree ..................................................15 3.2b Results from LTNS Student Surveys .............................................................16 3.3 The Curriculum ....................................................................................................... 37 3.3a Culminating Experience Requirement ......................................................... -

Wellesley College Bulletin

WELLESLEY COLLEGE BULLETIN ISSUE CONTAINING ANNUAL REPORTS FOR THE SESSIONS 1937-1938 WELLESLEY, MASSACHUSETTS DECEMBER, 1938 WELLESLEY COLLEGE BULLETIN ISSUE CONTAINING ANNUAL REPORTS FOR THE SESSIONS 1937-1938 Bulletins published seven times a year by Wellesley College, Wellesley, Massachusetts. April, 3; May, i; November, i; December, 2. Entered as second-class matter, February 12, 191 2, at the Post Office at Boston, Massachusetts, under the Act of July, 1894. Additional entry at Concord, N. H. Volume 28 Number 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Report of the President 5 Report of the Dean of the College 15 Report of the Dean of Freshmen 22 Report of the Committee on Graduate Instruction .... 26 Report of the Dean of Residence 31 Report of the Librarian 34 Report of the Director of the Personnel Bureau 52 Appendix to the President's Report: Legacies and Gifts 57 New Courses in 1938-39 60 Academic Biography of New Members of the Faculty and Administration, 1938-39 60 Leaves of Absence in 1938-39 63 Changes in Rank in 1938-39 63 Resignations and Expired Appointments, June 1938 ... 63 Fellowship and Graduate Scholarship Awards for 1938-39 65 Publications of the Faculty 65 Sunday Services 71 Addresses 72 Music 76 Exhibitions at the Art Museum 77 Report of the Treasurer 79 REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT To the Board oj Trustees: I have the honor to present the report of the year 1937-38, the sixty-third session of Wellesley College. The detailed state- ments from the administrative officers constitute a valuable record of the significant events and problems of the year. -

INTERSECTIONALITY UNDONE Saving Intersectionality from Feminist Intersectionality Studies 1

INTERSECTIONALITY UNDONE Saving Intersectionality from Feminist Intersectionality Studies 1 Sirma Bilge Département de sociologie, Université de Montréal Abstract This article identifies a set of power relations within contemporary feminist academic debates on intersectionality that work to “depoliticizing intersectionality,” neutralizing the critical potential of intersectionality for social justice-oriented change. At a time when intersectionality has received unprecedented international acclaim within feminist academic circles, a specifically disciplinary academic feminism in tune with the neoliberal knowledge economy engages in argumentative practices that reframe and undermine it. This article analyzes several specific trends in debate that neutralize the political potential of intersectionality, such as confining intersectionality to an academic exercise of metatheoretical contemplation, as well as “whitening intersectionality” through claims that intersectionality is “the brainchild of feminism” and requires a reformulated “broader genealogy of intersectionality.” Keywords: Intersectionality, Academic Feminism, Disciplinarity, Neoliberalism, Diver- sity, Postrace, Europe (Germany, France) INTRODUCTION This article identifies a set of power relations within contemporary feminist aca- demic debates on intersectionality that work to “depoliticizing intersectionality,” neutralizing the critical potential of intersectionality for social justice-oriented change. The overarching motivation behind the article is to explicate how intersectionality— -

What Is Racial Domination?

STATE OF THE ART WHAT IS RACIAL DOMINATION? Matthew Desmond Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Mustafa Emirbayer Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Abstract When students of race and racism seek direction, they can find no single comprehensive source that provides them with basic analytical guidance or that offers insights into the elementary forms of racial classification and domination. We believe the field would benefit greatly from such a source, and we attempt to offer one here. Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination so that students of the subjects—especially those seeking a general (if economical) introduction to the vast field of race studies—can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective (and fallacious) ways to think about racial domination. Focusing primarily on the American context, we begin by defining race and unpacking our definition. We then describe how our conception of race must be informed by those of ethnicity and nationhood. Next, we identify five fallacies to avoid when thinking about racism. Finally, we discuss the resilience of racial domination, concentrating on how all actors in a society gripped by racism reproduce the conditions of racial domination, as well as on the benefits and drawbacks of approaches that emphasize intersectionality. Keywords: Race, Race Theory, Racial Domination, Inequality, Intersectionality INTRODUCTION Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination, providing in a single essay a source through which thinkers—especially those seeking a general ~if economical! introduction to the vast field of race studies— can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective ways to think about racial domination. -

Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race INSTRUCTIONS for AUTHORS

Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race INSTRUCTIONS FOR AUTHORS EDITOR Aims and Scope Lawrence D. Bobo Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race (DBR) is an innovative periodical that presents and analyzes Harvard University the best cutting-edge research on race from the social sciences. It provides a forum for discussion and increased understanding of race and society from a range of disciplines, including but not limited to economics, political science, sociology, anthropology, law, communications, public policy, psychology, and history. Each issue of SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR DBR opens with remarks from the editors concerning the three subsequent and substantive sections: STATE Tommie Shelby OF THE D ISCIPLINE, where broad-gauge essays and provocative think-pieces appear; STATE OF THE A RT, dedicated Harvard University to observations and analyses of empirical research; and STATE OF THE DISCOURSE, featuring expansive book reviews, special feature essays, and occasionally, debates. For more information about the Du Bois Review ADVISORY BOARD please visit our website at http://hutchinscenter.fas.harvard.edu/du-bois-review or fi nd us on Facebook and Twitter. William Julius Wilson, Chair Manuscript Submission Harvard University DBR is a blind peer-reviewed journal. To be considered for publication in either STATE OF THE A RT or STATE Mahzarin Banaji Evelyn Nakano Glenn Lauren McLaren OF THE DISCIPLINE, an electronic copy of a manuscript (hard copies are not required) should be sent to: Harvard University University of California, Berkeley University of Nottingham Managing Editor, Du Bois Review, Hutchins Center, Harvard University, 104 Mount Auburn Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. -

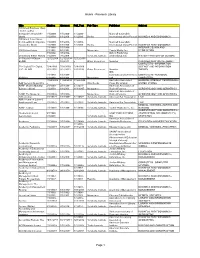

Research Library Page 1

Alumni - Research Library Title Citation Abstract Full_Text Pub Type Publisher Subject 100 Great Business Ideas : from Leading Companies Around the 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 100 Great Sales Ideas : from Leading Companies 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish Around the World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- INTERIOR DESIGN AND 1001 Home Ideas 6/1/1991 6/1/1991 Magazines Family Media, Inc. DECORATION 3/1/2002- 3/1/2002- Oxford Publishing 20 Century British History 7/1/2009 7/1/2009 Scholarly Journals Limited(England) HISTORY--HISTORY OF EUROPE 33 Charts [33 Charts - 12/12/2009 12/12/2009- 12/12/2009 BLOG] + 6/3/2011 + Other Resources Newstex CHILDREN AND YOUTH--ABOUT COMPUTERS--INFORMATION 50+ Digital [50+ Digital, 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- SCIENCE AND INFORMATION LLC - BLOG] 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 Other Resources Newstex THEORY IDG 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- Communications/Peterboro COMPUTERS--PERSONAL 80 Micro 6/1/1988 6/1/1988 Magazines ugh COMPUTERS 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 Australian Associated GENERAL INTEREST PERIODICALS-- AAP General News Wire + + + Wire Feeds Press Pty Limited UNITED STATES AARP Modern Maturity; 2/1/1988- 2/1/1988- 2/1/1991- American Association of [Library edition] 1/1/2003 1/1/2003 11/1/1997 Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS American Association of AARP The Magazine 3/1/2003+ 3/1/2003+ Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS ABA Journal 8/1/1972+ 1/1/1988+ 1/1/1992+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW ABA Journal of Labor & Employment Law 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW MEDICAL SCIENCES--NURSES AND ABNF Journal 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ Scholarly Journals Tucker Publications, Inc. -

Theory and Racialized Modernity: Du Bois in Ascendance

EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION Theory and Racialized Modernity Du Bois in Ascendance Lawrence D. Bobo Department of African and African American Studies and Department of Sociology , Harvard University The United States is neither done with race nor with the problem of racism. In this dilemma the U.S. is not alone. In Brazil and much of the rest of Latin America active pigmentocracies still relegate those of African descent and darker skinned indigenous peoples to the lower rungs of society (Gates 2011 ; Gudmunson and Wolfe, 2010 ; Hooker 2009 ; Joseph 2015 ; Telles 2014 ). Despite a great multiracial democratic revo- lution and the rise of numerous Black Africans into its economic elite, South Africa is far from done with the deep wounds and legacies of ongoing, vast Black poverty and economic marginalization attendant to its apartheid past (Gibson 2015 ; Nattrass and Seekings, 2001 ; Seekings 2008 ). Where it was once erected, although subject to much complexity and change in the modern era, the color line endures almost anywhere one looks around the globe. The notion of modernity we typically associate with two intersecting streams of ideas. One of these streams involves ideals of economic growth and development, free markets, and technological innovation. The other stream involves ideals of freedom, egalitarianism, and democracy. With the march forward of these intersecting streams much social thought foretold the withering of old ascriptive inequalities and barriers tied to racial and ethnic distinctions. But as ethnic studies scholar Elisa Joy White ( 2012 ) has put it, such “contemporary renderings of modernity are intrinsically flawed because of the structural antecedent of race-based social inequality” (p.