The Use of Weather Images by Canadian Ethnic Short Story Writers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interview with Dennis Bock

Read with us. February 15 – March 1, 2018 About the author Author Biography About the book An Interview with Dennis Bock Read on An Excerpt from Olympia The Communist’s Daughter by Dennis Bock An Excerpt from The Ash Garden Recommended Reading Web Detective Join the discussion at togetherweread.com The Communist’s Daughter by Dennis Bock February 15 – March 1, 2018 Author Biography Raised in Oakville, Ontario, Dennis Bock is one of five children born to German parents. His mother and father are both craftspeople: she, a weaver; he, a carpenter. The family lived near Lake Ontario, and Bock remembers his father building a sailboat in their basement, an experience that later influenced his short story collection,Olympia . There were few English-language books in his childhood home, so becoming a writer wasn’t Bock’s original career choice. As a boy, he dreamed of being a marine biologist. During high school, however, he got caught up in the magic of Gulliver’s Travels. “It was the first book I read with the understanding that someone’s mind had put all those words together— that someone’s imagination had constructed something that didn’t exist before.” After studying English and philosophy for three years at the University of Western Ontario, Bock set off for Spain. Wanderlust, he says, took him there. “Spain was the setting of some of my favourite stories and novels. I had a preconceived, literary notion of what it would look like. Of course, it was totally different.” He also wanted to experience dislocation and immigration, “to break down my elements.” While living in Madrid, Bock taught English as a foreign language and wrote short fiction. -

The Watermen Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE WATERMEN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patrick Easter | 416 pages | 21 Jun 2016 | Quercus Publishing | 9780857380562 | English | London, United Kingdom The Watermen PDF Book Read more Edit Did You Know? Pascoe, described as having blond hair worn in a ponytail, does have a certain Aubrey-ish aspect to him - and I like to think that some of the choices of phrasing in the novel may have been little references to O'Brian's canon by someone writing about the same era. Error rating book. Erich Maria Remarque. A clan of watermen capture a crew of sport fishermen who must then fight for their lives. The Red Daughter. William T. Captain J Ashley Myers This book is so engrossing that I've read it in the space of about four hours this evening. More filters. External Sites. Gripping stuff written by local boy Patrick Easter. Release Dates. Read it Forward Read it first. Dreamers of the Day. And I am suspicious of some of the obscenities. This thriller starts in medias res, as a girl is being hunter at night in the swamp by a couple of hulking goons in fishermen's attire. Lists with This Book. Essentially the plot trundles along as the characters figure out what's happening while you as the reader have been aware of everything for several chapters. An interesting look at London during the Napoleonic wars. Want to Read saving…. Brilliant book with a brilliant plot. Sign In. Luckily, the organiser of the Group, Diane, lent me her copy of his novel to re I was lucky enough to meet the Author, Patrick Easter at the Hailsham WI Book Club a month or so ago, and I have to say that the impression I had gained from him at the time was that he seemed to have certainly researched his subject well, and also had personal experience in policing albeit of the modern day variety. -

How to Submit to Literary Magazines

DON'T LET YOUR STORIES LANGUISH! HOW TO SUBMIT TO LITERARY MAGAZINES A LECTURE BY DORETTA LAU © DORETTA LAU, 2014 Congratulations on completing a short story! Now it's time to send it out for publication. © DORETTA LAU, 2014 AGENDA FOR TODAY'S TALK • Why you should submit to literary magazines • How to submit, broken down into simple steps © DORETTA LAU, 2014 MY EDITORIAL EXPERIENCE • As an undergraduate, I edited a literary magazine at The University of British Columbia called Uprooted. We published short fiction and poetry. • I was a first reader for PRISM International at UBC. • After graduate school I was an editorial assistant for a journal called NOON, which is edited by the American writer Diane Williams and showcases short fiction, essays, and art. • I worked as a production editor for the children's book publisher Scholastic Inc. • I currently work as a freelance copyeditor and proofreader. © DORETTA LAU, 2014 FROM A WRITER'S PERSPECTIVE MY STORY COLLECTION CONSISTS OF 12 STORIES, 8 OF WHICH WERE PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED IN LITERARY JOURNALS IN CANADA AND THE US. © DORETTA LAU, 2014 THE EIGHT PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED STORIES FROM MY COLLECTION • 2008: "Left and Leaving", Zen Monster • 2009: "O, Woe is Me", Grain Magazine • 2010: "Two-Part Invention", Grain Magazine • 2012: "How Does a Single Blade of Grass Thank the Sun?", Event • 2013: "Rerun", Grain Magazine • 2013: "Sad Ghosts", A Fictional Residency • 2013: "Days of Being Wild", Ricepaper • 2014: "Robot by the River", Day One © DORETTA LAU, 2014 WHY YOU SHOULD SUBMIT YOUR STORIES TO LITERARY MAGAZINES • Your story deserves an audience beyond your family, friends, and classmates. -

News from the Feminist Caucus, by Anne Burke Congratulations to The

News from the Feminist Caucus, by Anne Burke Congratulations to the finalists for the Pat Lowther Memorial Award and to all the poets and their publishers who entered the annual competition, as well as the 2014 judges. If you are in Toronto, please plan to join us on Friday, June 6, at 4 p.m. for the Open Reading and Business Meeting. Then on Saturday, June 7 4:15-5:15 p.m. for the panel Stories about the forgotten elders, our vulnerable elders – which prompted the panel topic, tentatively subtitled poetry and cautionary tales. This month, reviews of Nine Steps to the Door , by Maureen McCarthy, “Cold Surely Takes the Wood ”, by Tara Wohlberg; The New Blue Distance, Poems by Jeanette Lynes, Left Fields , by Jeanette Lynes; The M Word: Conversations about Motherhood , edited by Kerry Clare, Inheritance , by Kerry- Lee Powell, The L.M. Montgomery Reader , edited by Benjamin Lefebvre; Her Red Hair Rises With The Wings Of Insects, Poems , by Catherine Graham, and Once a murderer , by Zoe Landale. Unfortunately, Deirdre Dwyer's Going to the Eyestone and Eric Folsom's Icon Driven have just gone out of print. Review of Nine Steps to the Door , by Maureen McCarthy (North Vancouver: The Alfred Gustav Press, 2013) 18pp. paper Series Ten. The Alfred Gustav Press 429B Alder Street North Vancouver, BC V7L 1A9. The poet divides her strength between a branch and a twig, in order to wade into a stream. A room is depicted as old but like the heart it sleeps. A parrot ex cathedra. The nine steps occur in November. -

Spring/Summer 2021 Coach House Books

COACH HOUSE BOOKS SPRING/SUMMER 2021 COACH HOUSE BOOKS Publisher: Stan Bevington Editorial Director: Alana Wilcox Managing Editor: Crystal Sikma Sales and Marketing Coordinator: James Lindsay Digital and Distribution Coordinator: Nick Hilton Editorial Assistant: Tali Voron Digital Intern: Emily Hamilton Toronto Books Editor: John Lorinc 80 bpNichol Lane, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3J4, Canada Phone: 416 979 2217 | 1 800 367 6360 | Fax: 416 977 1158 www.chbooks.com | [email protected] Twitter: @coachhousebooks For ordering information, see back cover. For rights inquiries, please contact: [email protected] Other sales inquiries: [email protected] Permissions and desk copy requests: [email protected] Canadian media and publicity inquiries: [email protected] U.S. media and publicity inquiries, Cursor Marketing Services: [email protected] All other requests: [email protected] Coach House acknowledges the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Government of Ontario through Ontario Creates for our publishing activities. And Miles To Go Before I Sleep a novel by Jocelyne Saucier, translated by Rhonda Mullins Away From Her meets Strangers on a Train in this follow-up to cult bestseller And the Birds Rained Down. AfterAnd The Birds Rained Down, a stunning meditation on aging and freedom, Jocelyne Saucier is back with her unique outlook on self-determination in this unsettling story about a woman’s disappearance. Gladys might look old and frail, but she is determined to finish her life on her own terms. And so, one September morning, she leaves Swastika, her home of the past fifty years, and hops on the Northlander train, eager to put thousands of miles of northern Quebec between her and the improbably named village, and leaving behind her perennially tormented daughter, Lisana. -

Harpercollins Uk Fiction Rights Guide Frankfurt 2018

TABLE OF CONTENTS • NEW TITLES……………………………………...….4 • HISTORICAL FICTION……………………...…..…26 • CRIME AND THRILLER……………………….....…36 • BOOK CLUB AND WOMEN’S FICTION….…..….53 • LITERARY…………………………………….….…64 • FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION……….……..68 • ROMANCE………………………………………...73 • EMOTIONAL ……………………………….…….85 • TOLKIEN AND FANTASTIC BEASTS……………88 • SAGA………………………………………………94 • DIGITAL FIRST PUBLISHING………………….....103 • RECENTLY PUBLISHED………………………….142 NEW TITLES SLENDER MAN Anonymous A horror movie based on the Slender Man myth was released in September 2018 Slender Man is one of the internet’s most notorious creations – a shadowy figure whose victims disappear or find themselves doing 20 Sep 2018 terrible things. This is the first official Slender Man book. £9.99 In 2016, Netflix released a documentary, “Beware the Slender Man”, 216x135 exploring the phenomenon Hardback 336pp LAUREN BAILEY HAS DISAPPEARED. About the author As her friends and the police search for answers, Matt Barker begins to These documents were collected dream of trees and black skies and something drawing closer. by sources who wish to remain Through fragments of journals, blog posts and messages, a sinister, anonymous. slender figure emerges and all divisions between fiction and delusion, between nightmare and reality, begin to fall. The urban legend of the Slender Man has inspired short fiction, viral videos, and a feature film. Gathered from online whispers, Matt’s story reveals the true power of the internet’s most terrifying creation. HarperCollins (Italian) HARPERCOLLINSPUBLISHERS 5 FRANKFURT BOOK FAIR 2018 TAKE IT BACK Kia Abdullah Take It Back is a thrilling courtroom drama that’s perfect for fans of Anatomy of a Scandal, He Said/She Said and Apple Tree Yard. Zara is a strong, intelligent, and fearless heroine who is sure to win over readers. -

University of Groningen Souvenirs Et Découvertes Den Toonder, Jeanette

University of Groningen Souvenirs et découvertes den Toonder, Jeanette Published in: Canadian Literature IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2006 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): den Toonder, J. (2006). Souvenirs et découvertes: Janine Ricouart and Roseanna L. Dufault Les secrets de la Sphinxe: Lectures de l’œuvre d’Anne-Marie Alonzo. Éditions du Remue-Ménage, Louise Desjardins and Mona Latif-Ghattas Momo et Loulou. Éditions du Remue-Ménage . Canadian Literature, (191), 125- 126. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 191CanLitWinter2006-4 1/23/07 1:04 PM Page 1 Canadian Literature/ Littératurecanadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number , Winter Published by The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Laurie Ricou Associate Editors: Laura Moss (Reviews), Glenn Deer (Reviews), Kevin McNeilly (Poetry), Réjean Beaudoin (Francophone Writing), Judy Brown (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (1959–1977), W.H. -

Program Guide a Festival for Readers and Writers

PROGRAM GUIDE A FESTIVAL FOR READERS AND WRITERS SEPTEMBER 25 – 29, 2019 HOLIDAY INN KINGSTON WATERFRONT penguinrandomca penguinrandomhouse.ca M.G. Vassanji Anakana Schofield Steven Price Dave Meslin Guy Gavriel Kay Jill Heinerth Elizabeth Hay Cary Fagan Michael Crummey KINGSTON WRITERSFEST PROUD SPONSOR OF PROUD SPONSOR OF KINGSTON WRITERSFEST Michael Crummey Cary Fagan Elizabeth Hay FULL PAGEJill Heinerth AD Guy Gavriel Kay Dave Meslin Steven Price Anakana Schofield M.G. Vassanji penguinrandomhouse.ca penguinrandomca Artistic Director's Message ow to sum up a year’s activity in a few paragraphs? One Hthing is for sure; the team has not rested on its laurels after a bang-up tenth annual festival in 2018. We’ve focussed our sights on the future, and considered how to make our festival more diverse, intriguing, relevant, inclusive and welcoming of those who don’t yet know what they’ve been missing, and those who may have felt it wasn’t a place for them. To all newcomers, welcome! We’ve programmed the most diverse festival yet. It wasn’t hard to fnd a range of stunning new writers in all genres, and seasoned writers with powerful new works. We’ve included the stories of women, the stories of Indigenous writers, Métis writers, writers of different experiences, cultural backgrounds, and orientations. Our individual and collective experience and understanding are sure to be enriched by these fresh perspectives, and new insights into the past. We haven’t forgotten our roots in good story-telling, presenting a variety of uplifting, entertaining, and thought-provoking fction and non-fction events. -

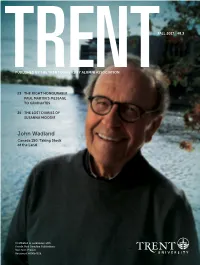

TRENT Magazine 48.3 3 EDITOR’S NOTES

FALL 2017 48.3 PUBLISHED BY THE TRENT UNIVERSITY ALUMNI ASSOCIATION 23 THE RIGHT HONOURABLE PAUL MARTIN’S MESSAGE TO GRADUATES 25 THE LOST DIARIES OF SUSANNA MOODIE John Wadland Canada 150: Taking Stock of the Land Little Feet. Big Responsibility. Looking after your family is not just about today’s new shoes, it’s about always. Our Term Life Insurance lets you live life fully and enjoy every moment, confident that you have provided for the future of those most important to you. Term Life Insurance For a personalized quotation or to apply online, please visit us at: solutionsinsurance.com/trent 1.800.266.5667 Underwritten by Industrial Alliance Insurance & Financial Services Inc. iA Financial Group is a business name and trademark of Industrial Alliance Insurance and Financial Services Inc. TRENT is published three times a year in June, November and February by the Trent University Alumni Association. Unsigned comments reflect the opinion of the editor only. Trent University Alumni Association Alumni House, Champlain College Trent University Peterborough, Ontario, K9L 0G2 705.748.1573 or 1.800.267.5774, Fax: 705.748.1785 Email: [email protected] trentu.ca/alumni EDITOR • MANAGING EDITOR Donald Fraser ’91 COPY EDITOR Megan Ward DESIGN Beeline Design & Communications CONTRIBUTORS Dakota Brant ’06, Donald Fraser ’91, 36 Jess Grover ’02, Melissa Moroney, Tom Phillips ’74, Kathryn Verhulst-Rogers, Cecily Ross ’83, John Wadland, Kate Weersink, Trevor Corkum ’94 EDITORIAL BOARD 4 | Editorial Marilyn Burns ’00, Sebastian Cosgrove ’06, 5 | University President’s Message Donald Fraser ’91, Lee Hays ’91, Melissa Moroney, Ian Proudfoot ’73 6 | What’s New at Trent PRINTING and BINDING Maracle Press, Oshawa 8 | Spotlight on Research TUAA COUNCIL HONORARY PRESIDENT 10 | Virtual Medicine T.H.B. -

Exile Editions 2020

2020 AUTUMN CATALOGUE PLUS 2019 RELEASES RE-PRESENTED RECENT HIGHLIGHTS At Exile we envision, create, assist, and present the future of literary and visual arts in Canada by publishing personal, provocative, innovative, and often experimental stories that reflect the Canadian experience. To promote our books we use a mixture of traditional reading/review copies, as well as online resources such as NetGalley, and social media posts, ads, reviews, blogs, and savvy influencers to get the word out. For all publishing related inquiries: info @exileeditions.com 519 334 3634 www.ExileEditions.com Exile Editions, 144483 Southgate Road 14-GD, Holstein, ON, N0G 2A0, Canada Sales: Distribution: Returns: Canadian Manda Group Independent Publishers Group IPG c/o Fraser Direct 664 Annette Street 814 North Franklin Street, 8300 Lawson Road Toronto, ON, M6S 2C8 Chicago, IL, 60610 USA Milton, ON, L9T 0A4 www.mandagroup.com www.ipgbook.com 905-877-4411 416-516-0911 toll free: 1-800-888-4741 The publisher would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Ontario Media Development Corporation, for our publishing activities. $16.95US$ y r t e o P TO YOUR SCATTERED BODIES GO BRIAN BRETT Writing so vivid, observations so telling, these poems are a thoroughly perceptive appreciation of the human predicament that it is all together sobering and profound. OCTOBER 15 5 x 7.5 TPB 144 pages 978-1-55096-889-7 $19.95 Born to be an outsider because of a rare genetic dis - order, Kallmann syndrome, Brian Brett lived an androgy - nous childhood of abuse and sexual harassment. -

Fall 2013 September – December for the Most Up-To-Date Edelweiss Catalog Information, Visit Contents

BloomsBury Fall 2013 september – december For the most up-to-date Edelweiss catalog information, visit http://edelweiss.abovethetreeline.com CONTENTS BLOOMSBURY ROY G. BIV Jude Stewart 4 The Bone Season Samantha Shannon 5 Rambunctious Garden (pb) Emma Marris 7 On the Trail of Genghis Khan Tim Cope 8 Men We Reaped Jesmyn Ward 9 Just Plain Dick (pb) Kevin Mattson 11 Becoming a Londoner David Plante 12 The Wild Duck Chase (pb) Martin J. Smith 13 Others of My Kind James Sallis 14 The Shadow Scholar (pb) Dave Tomar 15 Marilyn (pb) Lois Banner 16 The Two Hotel Francforts David Leavitt 17 An Emergency in Slow Motion (pb) William Todd Schultz 19 Torment Saint William Todd Schultz 20 Writing on the Wall Tom Standage 21 Margaret Thatcher Jonathan Aitken 23 In Calamity’s Wake Natalee Caple 24 WWW The Kennedy Half-Century Larry J. Sabato 25 . Hard Twisted (pb) C. Joseph Greaves 27 B Whatever Happened to the Metric System? John Bemelmans Marciano 28 LOOMS Beasts Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson 29 Zoo Time (pb) Howard Jacobson 31 B Leonardo and the Last Supper (pb) Ross King 32 URY.COM The Simpsons and Their Mathematical Secrets Simon Singh 33 If Walls Could Talk (pb) Lucy Worsley 35 The Ukulele Handbook Tom Hodgkinson and Gavin Pretor-Pinney 36 The Teleportation Accident (pb) Ned Beauman 37 Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink John F. Mariani 38 The Art of Losing (pb) Kevin Young 39 Home Fires Elizabeth Day 40 Fire in the Belly (pb) Cynthia Carr 41 Owning the Earth Andro Linklater 42 Let Me Tell You a Story Renata Calverley 43 Glorious Misadventures Owen Matthews 44 Historic Blumenthal Heston Blumenthal 45 Respect Yourself Robert Gordon 46 Mirror Earth (pb) Michael D. -

Contents: 1. Canadian Awards 2. Canadian Regional Awards 3

Contents: 1. Canadian Awards 2. Canadian Regional Awards 3. International Awards This document focuses primarily on awards for adult literature. A comprehensive list of children’s book awards (both Canadian and international) is available from this infrequently-updated University of Calgary website compiled by David K. Brown: http://wiki.ucalgary.ca/page/ChildrensLiteratureWebGuide or from the Amazon sponsored site: http://www.canlitawards.com/cankids.html. Arthur Ellis Award http://www.crimewriterscanada.com/awards/arthur-ellis-awards/current-contest Awards for Canadian crime and mystery fiction, administered by the Crime Writers of Canada. The awards are named after the nom de travail of Canada's official hangmen. Awards are presented in six categories for works in the crime genre published for the first time in the previous year by authors living in Canada, regardless of their nationality, or by Canadian writers living outside of Canada. For past winners see: http://www.crimewriterscanada.com/awards/arthur-ellis- awards/past-winners Canada Reads http://www.cbc.ca/canadareads/ Canada Reads is a CBC Radio program about books that's designed to appeal to both avid and occasional readers. Five celebrity panelists each champion a work of Canadian fiction they'd love us all to read and, in a game of ―literary survivor,‖ whittle down that list of books to one, the book Canada Reads. Canadian Authors’ Association Awards http://www.canauthors.org/awards/winners.html These awards annually recognize Canadian literary excellence in adult literature, poetry, Canadian history, drama, and television. Canadian Science Writers' Association Awards http://www.sciencewriters.ca/awards/index.html The Canadian Science Writers' Association offers print, radio, and television awards annually to honour outstanding Canadian science journalism in short and long format catagories.