Notes on the Algorithmic Soccer Referee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steven Gerrard Autobiografia

STEVEN GERRARD AUTOBIOGRAFIA Tłumaczenie LFC.pl Drodzy Paostwo! Jeśli macie przed sobą tą książkę z nadzieją, by dowiedzied się tylko o karierze Stevena Gerrarda to prawdopodobnie się zawiedziecie. Jeżeli jednak pragniecie przeczytad o życiu i sukcesach Naszego kapitana to nie mogliście lepiej trafid. Steven Gerrard to bohater dla wielu milionów, nie tylko kapitan Liverpool Football Club, ale także ważny element reprezentacji Anglii. ‘Gerro’ po raz pierwszy opowiedział historię swojego życia, które od najmłodszych lat było przepełnione futbolem. Ze pełną szczerością wprowadził czytelnika w swoje prywatne życie przywołując dramatyczne chwile swojego dzieciostwa, a także początki w Liverpoolu i sukcesy jak niewiarygodny finał w Stambule w maju 2005 roku. Steven ukazuje wszystkim, jak ważne miejsce w jego sercu zajmuje rodzina a także zdradza wiele sekretów z szatni. Oddajemy do Paostwa dyspozycji całośd biografii Gerrarda z nadzieją, iż się nie zawiedziecie i ochoczo przystąpicie do lektury, która niejednokrotnie może doprowadzid do wzruszenia. Jeśli Steven nie jest jeszcze Waszym bohaterem, po przeczytaniu tego z pewnością będzie ... Adrian Kijewski redaktor naczelny LFC.pl Oryginał: Autor: Steven Gerrard Rok wydania: 2006 Wydawca: Bantam Press W tłumaczeniu książki uczestniczyli: Katarzyna Buczyoska (12 rozdziałów) Damian Szymandera (8 rozdziałów) Angelika Czupryoska (1 rozdział) Grzegorz Klimek (1 rozdział) Krzysztof Pisarski (1 rozdział) Redakcja serwisu LFC.pl odpowiedzialna jest tylko i wyłącznie za tłumaczenie oryginału na język Polski, nie przypisujemy sobie tym samym praw do tekstu wydanego przez Bentam Press. Polska wersja, przetłumaczona przez LFC.pl, nie może byd sprzedawana. Steven Gerrard – Autobiografia (tłumaczenie LFC.pl) Strona 2 Wstęp iedy tylko przyjeżdżam na Anfield zwalniam przy Shankly Gates. Jednocześnie kieruje wzrok na Hillsborough Memorial. -

Trivial Laws of the Game 2012-2013

Trivial Laws of the Game 2012-2013 Temporada 2012-2013 EASY LEVEL: 320 QUESTIONS 1.- How far is the penalty mark from the goal line? a) 10m (11yds) b) 11m (12yds) c) 9m (10yds) d) 12m (13yds) Respuesta: b 2.- What is the minimum width of a standard field of play? a) 45m (50yds) b) 50m (55yds) c) 40m (45yds) d) 55m (60yds) Respuesta: a 3.- Goal nets... a) must be attached. b) can be used but it depends on the rules of the competition. c) may be attached to the goals and ground behind the goal. d) are required. Respuesta: c 4.- Indicate which of the following statements about the ball is not correct: a) It should be spherical. b) It should have a circumference of not more than 70 cm and not less than 68 cm. c) Should weigh not more than 450g and not less than 420g at the beginning of the match. d) It should be leather or another suitable material. Respuesta: c 5.- Halfway line flagposts... a) must be placed at a distance of 1m (1yd) from each end of the halfway line. b) are positioned on the touch line at each end of the halfway line. c) may be placed at a distance of 1m (1yd) from each end of the halfway line. d) must be placed at a distance of at least 1.5m (1.5yd) from each end of the halfway line. Respuesta: c 6.- Who should the referee inform of any irregularities in the field of play? a) The organisers of the match. -

Mundiales.Pdf

Dr. Máximo Percovich LOS CAMPEONATOS MUNDIALES DE FÚTBOL. UNA FORMA DIFERENTE DE CONTAR LA HISTORIA. - 1 - Esta obra ha sido registrada en la oficina de REGISTRO DE DERECHOS DE AUTOR con sede en la Biblioteca Nacional Dámaso Antonio Larrañaga, encontrándose inscripta en el libro 33 con el Nº 1601 Diseño y edición: Máximo Percovich Diseño y fotografía de tapa: Máximo Percovich. Contacto con el autor: [email protected] - 2 - A Martina Percovich Bello, que según muchos es mi “clon”. A Juan Manuel Nieto Percovich, mi sobrino y amigo. A Margarita, Pedro y mi sobrina Lucía. A mis padres Marilú y Lito, que hace años que no están. A mi tía Olga Percovich Aguilar y a Irma Lacuesta Méndez, que tampoco están. A María Calfani, otra madre. A Eduardo Barbat Parffit, mi maestro de segundo año. A todos quienes considero mis amigos. A mis viejos maestros, profesores y compañeros de la escuela y el liceo. A la Generación 1983 de la Facultad de Veterinaria. A Uruguay Nieto Liszardy, un sabio. A los ex compañeros de transmisiones deportivas de Delta FM en José P. Varela. A la memoria de Alberto Urrusty Olivera, el “Vasco”, quien un día me escuchó comentar un partido por la radio y nunca más pude olvidar su elogio. A la memoria del Padre Antonio Clavé, catalán y culé recalcitrante, A Homero Mieres Medina, otro sabio. A Jorge Pasculli. - 3 - - 4 - Máximo Jorge Percovich Esmaiel, nacido en la ciudad de Minas –Lavalleja, Uruguay– el 14 de mayo de 1964, es un Médico Veterinario graduado en la Universidad de la República Oriental del Uruguay, actividad esta que alterna con la docencia. -

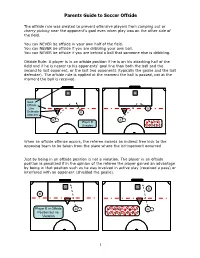

Parents Guide to Soccer Offside

Parents Guide to Soccer Offside The offside rule was created to prevent offensive players from camping out or cherry picking near the opponent’s goal even when play was on the other side of the field. You can NEVER be offside in your own half of the field. You can NEVER be offside if you are dribbling your own ball. You can NEVER be offside if you are behind a ball that someone else is dribbling. Offside Rule: A player is in an offside position if he is on his attacking half of the field and if he is nearer to his opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second to last opponent, or the last two opponents (typically the goalie and the last defender). The offside rule is applied at the moment the ball is passed, not at the moment the ball is received. G G Goal Offside Line B Defender B Attacker A A Player B Player B Onsides OFFSIDES When an offside offence occurs, the referee awards an indirect free kick to the opposing team to be taken from the place where the infringement occurred Just by being in an offside position is not a violation. The player in an offside position is penalized if in the opinion of the referee the player gained an advantage by being in that position such as he was involved in active play (received a pass) or interfered with an opponent (shielded the goalie). G G B B Player B in Offside A OFFSIDES – Player B A Position but no Is involved in the play Violation 1 Parents Guide to Soccer Offside NO OFFENSE: There is no offside offense if a player receives the ball directly from: • a goal kick • a throw-in • a corner kick A G G B B No Offside on Corner Kicks A No Offside on Throw-Ins Figures 1 & 2 - The offside rule is applied at the moment the ball is passed, not at the moment the ball is received. -

The Causes of the Civil War

THE CAUSES OF THE CIVIL WAR: A NEWSPAPER ANALYSIS by DIANNE M. BRAGG WM. DAVID SLOAN, COMMITTEE CHAIR GEORGE RABLE MEG LAMME KARLA K. GOWER CHRIS ROBERTS A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Communication and Information Sciences in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2013 Copyright Dianne Marie Bragg 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation examines antebellum newspaper content in an attempt to add to the historical understanding of the causes of the Civil War. Numerous historians have studied the Civil War and its causes, but this study will use only newspapers to examine what they can show about the causes that eventually led the country to war. Newspapers have long chronicled events in American history, and they offer valuable information about the issues and concerns of their communities. This study begins with an overview of the newspaper coverage of the tariff and territorial issues that began to divide the country in the early decades of the 1800s. The study then moves from the Wilmot Proviso in 1846 to Lincoln’s election in 1860, a period in which sectionalism and disunion increasingly appeared on newspaper pages and the lines of disagreement between the North and the South hardened. The primary sources used in this study were a diverse sampling of articles from newspapers around the country and includes representation from both southern and northern newspapers. Studying these antebellum newspapers offers insight into the political, social, and economic concerns of the day, which can give an indication of how the sectional differences in these areas became so divisive. -

L@B@C@F@K 3 QUAND LE FOOTBALL

Bleu Rouge 1 Noir Jaune 61e ANNÉE - No 19 141 1,80 / France métropolitaine Samedi 25 novembre 2006 www.lequipe.fr * ; SPÉCIAL NEIGE AVEC E DÉNÉRIAZ 1,80 ET LE GUIDE F: DES STATIONS - 1125 M 00103 AUJOURD’HUI LE MAGAZINE LE QUOTIDIEN DU SPORT ET DE L’AUTOMOBILE :HIKKLA=XUV]UZ:?l@b@c@f@k 3 QUAND LE FOOTBALL La mort d’un supporter du Paris-SG, TOLÉRANCE ZÉRO tué par un policier E foot n’est pas guéri », titrait L’Équipe «L le 8 novembre, alors que l’Europe tout jeudi soir aux abords entière subissait une nouvelle vague de violence. Depuis le drame de la porte de du Parc des Princes Saint-Cloud, jeudi soir, à l’issue de la après la défaite rencontre Paris-SG - Hapoël Tel-Aviv, nous Noir Bleu savons qu’il est même très gravement face aux Israéliens malade, bien plus que ses propres dirigeants Noir Bleu le croient ou tentent de le faire croire. La de l’Hapoël Tel-Aviv (2-4), question n’est pas tant celle du remède – il en existe de très efficaces, on le sait – que Rouge Jaune TUE celle de la responsabilité des praticiens. rappelle tragiquement Rouge Un homme est mort. Un autre est grièvement Jaune que le football français blessé. Un troisième a été agressé parce qu’il était noir et policier. Un quatrième a failli n’a pas su éradiquer être molesté parce qu’il était supporter d’un club israélien. Comment en est-on arrivé là ? la violence et le racisme Quelles sont les erreurs, les manquements, les complicités – y compris passives –, présents dans les tribunes les lâchetés qui ont provoqué ce désastre ? Quelles sont les mauvaises raisons qu’on de quelques clubs. -

Law 8 - Start & Restart of Play

Law 8 - Start & Restart of Play U.S. Soccer Federation Referee Program Entry Level Referee Course Competitive Youth Training Small Sided and Recreational Youth Training 2016-17 Coin Toss The game starts with a kick- off and that’s decided by the coin toss. The coin toss usually takes place with the designated team captains. The visiting captain usually gets to select heads or tails before the coin is tossed by the referee. Coin Toss The winner of the coin toss selects which goal they will attack in the first half (or period). The other team must then take the kick-off to start the game. In the second half (or period) of the game, the teams change ends and attack the opposite goals. The team that won the coin toss takes the kick-off to start the second half (or period). Kick-off The kick-off is used to start the game and to start any other period of play as dictated by the local rules of competition. First half . Second half . Any add’l periods of play A kick-off is also used to restart the game after a goal has been scored. Kick-off Mechanics . The referee crew enters the field together prior to the opening kick-off. They move to the center mark, the referee carries the ball. Following final instructions and a handshake, the ARs go to their respective goals lines, do a final check of the goals/nets and then move to their positions on the touch lines. Kick-off Mechanics . Before kick-off, the referee looks over the field & players and makes eye contact with both ARs. -

Legea, Nasce Agli Inizi Degli Anni Novanta, a Pompei Dai Coniugi Acanfora

STORIA DEL MARCHIO Il marchio Legea, nasce agli inizi degli anni novanta, a Pompei dai coniugi Acanfora. Produce prevalentemente abbigliamento e accessori per il calcio. Successivamente, si specializza nella produzione di materiale tecnico per altre discipline sportive. L’evoluzione e la crescita dell’azienda sono dovute: • La sponsorizzazione nel 2003 del Napoli calcio • La collaborazione con le squadre del Montenegro e di Gibilterra e di altre squadre italiane in serie C. • Nel 2019/2020 l’accordo con la FIGC per la fornitura dell’abbigliamento sportivo dell’Associazione Italiana Arbitri PUNTI DI FORZA DELL’AZIENDA • Ottimo rapporto qualità prezzo • start-up control: l’affiliato è seguito nelle varie fasi fino all’apertura dello store • Costi di affiliazione pari allo zero • Rapidità di evasione degli ordini MADE IN ITALY? • Fornitori : sconosciuti. Inizialmente si parlava di made in Italy. • Legea è stata al centro di una vicenda giudiziaria: infatti l’azienda aveva fatto produrre i suoi prodotti in Cina e li aveva poi importati in Italia, apponendovi poi il marchio dell’azienda. • La Cassazione però ha rigettato il ricorso del Procuratore di Napoli, rilevando che la qualità dei prodotti dipende dall’identità del produttore e non dall’ambiente geografico di fabbricazione. • Il comportamento della Legea non ha quindi integrato il reato. CLIENTI Legea ha una clientela in cinquanta paesi, nei più importanti continenti. In Italia sono presenti 180 store mono-marchio i c.d. «Legea Point» Ha intrapreso diverse relazioni di sponsorship in varie società sportive calcistiche. CONCORRENTI DEL SETTORE CONCORRENTI La concorrenza nell’abbigliamento sportivo è forte. I principali concorrenti sono Nike con l’15,61% e Adidas con l’11,81% del mercato, con prodotti ad alto costo e alta qualità. -

David Luiz Cele- and the Players We’Ve Got

TUESDAY, JULY 8, 2014 A look back at five memorable WCup semi-final classics RIO DE JANEIRO: With two potentially epic semi-finals struck again with Gerd Mueller putting them 2-1 Amoros hit the crossbar in stoppage time. Another iconic moment followed as German cap- in prospect this week between Brazil and Germany ahead to start a frantic burst of five goals in 17 min- Justice appeared to be done when Marius Tresor tain Lothar Matthaeus consoled a distraught Waddle and Argentina and the Netherlands, Reuters takes a utes. Tarcisio Burgnich made it 2-2 before Gigi Riva put and Alain Giresse struck to put France 3-1 ahead after after the game. look back at five classic World Cup semi-finals. the Italians back in front later with a shot on the turn. 98, but with injured captain Karl-Heinz Rummenigge The other semi-final between hosts Italy and That lead only last six minutes before Mueller scored coming off the bench to lead the fightback, the Argentina also ended in a 1-1 draw and a 4-3 penalty Stockholm June 24 1958 BRAZIL 5 FRANCE 2 to make it 3-3. The Italians went straight up the other Germans pulled level with goals from Rummenigge shootout victory for the Argentines who lost 1-0 to the Pele, who was 17-years-old, had scored his first end with Gianni Rivera striking in the 111th minute to and Klaus Fischer before they won in the World Cup’s Germans in the final. World Cup goal in Brazil’s 1-0 win over Wales in the make it 4-3. -

The British Press and Zionism in Herzl's Time (1895-1904)* BENJAMIN JAFFE, MA., M.Jur

The British Press and Zionism in Herzl's Time (1895-1904)* BENJAMIN JAFFE, MA., M.Jur. A but has been extremely influential; on the other hand, it is not easy, and may even be It is a to to the Historical privilege speak Jewish to evaluate in most cases a impossible, public Society on subject which is very much interest in a subject according to items or related to its founder and past President, articles in a published newspapers many years the late Lucien Wolf. Wolf has prominent ago. It is clear that Zionism was at the period place in my research, owing to his early in question a marginal topic from the point of contacts with Herzl and his opposition to view of the public, and the Near East issue Zionism in later an which years, opposition was not in the forefront of such interest. him to his latest The accompanied day. story We have also to take into account that the of the Herzl-Wolf relationship is an interesting number of British Jews was then much smaller chapter in the history of early British Zionism than today, and the Jewish public as newspaper and Wolf's life.i readers was limited, having It was not an venture to naturally quite easy prepare were regard also to the fact that many of them comprehensive research on the attitude of the newly arrived immigrants who could not yet British press at the time of Herzl. Early read English. Zionism in in attracted England general only I have concentrated here on Zionism as few scholars, unless one mentions Josef Fraenkel reflected in the British press in HerzPs time, and the late Oskar K. -

The Changing Meanings of the 1930S Cinema in Nottingham

FROM MODERNITY TO MEMORIAL: The Changing Meanings of the 1930s Cinema in Nottingham By Sarah Stubbings, BA, MA. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, August 2003 c1INGy G2ýPF 1sinr Uß CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgements ii Introduction 1 PART ONE: CONTEMPORARY REPORTING OF THE 1930S CINEMA 1. Contested Space, Leisure and Consumption: The 1929 36 Reconstruction of the Market Place and its Impact on Cinema and the City 2. Luxury in Suburbia: The Modern, Feminised Cinemas of 73 the 1930s 3. Selling Cinema: How Advertisements and Promotional 108 Features Helped to Formulate the 1930s Cinema Discourse 4. Concerns Over Cinema: Perceptions of the Moral and 144 Physical Danger of Going to the Pictures PART TWO: RETROSPECTIVECOVERAGE OF THE 1930S CINEMA 5. The Post-war Fate of the 1930s Cinemas: Cinema Closures - 173 The 1950s and 1960s 6. Modernity and Modernisation: Cinema's Attempted 204 Transformation in the 1950s and 1960s 7. The Continued Presence of the Past: Popular Memory of 231 Cinema-going in the 'Golden Age' 8. Preserving the Past, Changing the Present? Cinema 260 Conservation: Its Context and Meanings Conclusion 292 Bibliography 298 ABSTRACT This work examines local press reporting of the 1930s cinema from 1930 up to the present day. By focusing on one particular city, Nottingham, I formulate an analysis of the place that cinema has occupied in the city's history. Utilising the local press as the primary source enables me to situate the discourses on the cinema building and the practice of cinema-going within the broader socio-cultural contexts and history of the city. -

January 2018.Pub

@ WokingRA PRESIDENT Vince Penfold Chairman Life Vice Presidents Pat Bakhuizen David Cooper, Chris Jones, Ken Chivers , 07834 963821 Neil Collins, Peter Guest, Roy Butler Vice Chairman Secretary Anthony (Mac) McBirnie (see Editor) Colin Barnett Assistant Sec Andy Bennett Treasurer and Membership Secretary Editor : The Warbler Bryan Jackson 01483 423808 Mac McBirnie, 01483 835717 / 07770 643229 1 Woodstock Grove, Godalming, Surrey, GU7 2AX [email protected] Training Officer Supplies Officer ; Callum Peter Gareth Heighes [email protected] 07951 425179 Assistant Tom Knight (pending) R.A Delegates Committee Brian Reader 01483 480651 Barry Rowland, Tony Price , Tom Ellsmore, Tony Loveridge Martin Read, Paul Saunders, Dave Lawton Friends of Woking Referees Society Roy Lomax ; Andy Dexter; Pam Wells ; Tom Jackson ; Mick Lawrence ; Lee Peter ; Jim D’Rennes : Eamonn Smith Affiliate Member Ian Ransom INSIDE THIS MONTH’S WARBLER Page 3: Agenda Page 4 : From the Chair /Accounts /Membership Page 5: Just a Sec / Mac’s Musings Page 6 : A Christmas Quiz Page 7 : SCRA Report / This Month’s Speaker Page 8: Handball ! Its Not Black and White : Tim Vickery Page 9 : Video Ref Reversal : Via Mal Davies Page10 /11 Abuse of Power : Edward Eason ( The Guardian) Page 12 : Murphy’s Meanderings Page 13 : Refereeing is an Obsession : Neale Barry Page 14 : Diving Judges : Brian Richards Page 15 : Plum Tree / Dates for Your Diary Page 16 : English Women Referees Challenge : Dick Sawden-Smith Page 17 : Letters to the Editor : Dick Sawden—Smith Page 18 : Pitch