University of California, Los Angeles Have

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUNNING HEAD: Aging in the Context of Immigration and Care Labour

RUNNING HEAD: Aging in the context of immigration and care labour Aging in the context of immigration and care labour: The experiences of older Filipinos in Canada A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of a Ph.D. in Social Work Ilyan Ferrer School of Social Work McGill University, Montreal JUNE 2018 © Ilyan Ferrer, 2018 Abstract This doctoral dissertation examines how the intersections of immigration, labour, and care impact the late life experiences of older Filipinos in Canada. A critical ethnography was adopted to understand the interplay of lived experiences, identities, and policies (specifically related to retirement, aging, and immigration). Extended observations and in-depth semi-structured interviews with 18 older people, 6 adult children, and 13 community stakeholders identified the structural barriers that impinged on everyday experiences of aging within the Filipino Canadian diaspora living in Montreal. Several themes emerged including (1) the disjuncture between discourses on immigration and migration and the ways in which older racialized newcomers are welcomed into Canadian society, (2) the intersections between immigration and retirement policies and their impact on older Filipina women engaged in domestic work, and (3) the ways in which Filipino older adults provide and receive care in intergenerational and transnational settings in response to the paucity and scarcity of formal resources. The findings of this study offer new knowledge about the impact of immigration and labour policies on the lived experiences of aging and care practices among older members of racialized and immigrant communities in the Global North generally, and within Filipino communities in Canada specifically. -

White Rabbit Creamy Candy and Bairong Grape Biscuits from China Safe for Consumption

Agri-Food & Veterinary Authority of Singapore 5 Maxwell Road #04-00 Tower Block MND Complex Singapore 069110 Fax: (65) 62235383 WHITE RABBIT CREAMY CANDY AND BAIRONG GRAPE BISCUITS FROM CHINA SAFE FOR CONSUMPTION The Agri-Food & Veterinary Authority (AVA) has conducted tests on the White Rabbit Creamy Candy and Bairong Grape Biscuits from China and found them to be safe for consumption. 2 The tests were conducted following reports that four products - White Rabbit Creamy Candy, Milk Candy, Balron Grape Biscuits and Yong Kang Foods Grape Biscuits – were withdrawn by the Philippines’ Food and Drug Agency for possible formaldehyde contamination. Of these products, only the White Rabbit Creamy Candy is imported into Singapore. However, Singapore also imports Bairong Grape Biscuits, which has a similar name to Balron Grape Biscuits. Samples of both Bairong Grape Biscuits and White Rabbit Creamy Candy were taken for testing. 3 Formaldehyde is a chemical that is not permitted for use as a food additive. However, formaldehyde occurs naturally at low levels in a wide range of foods. The World Health Organization (WHO) has established a Tolerable Daily Intake (TDI) of 0.15 mg/kg body weight for formaldehyde. 4 Our tests indicate that there were minute amounts of formaldehyde in the samples of White Rabbit Creamy Candy and Bairong Grape Biscuits tested. However, based on the TDI established by WHO, normal consumption of these products would not pose a health risk. The presence of the minute amounts of formaldehyde could be due to its natural occurrence in the ingredients used for making the products. There is no evidence to suggest that formaldehyde was added into the products as a preservative. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Auntie's Wok & Steam Menu

LUNCH TRAY SETS Monday - Friday 12:00pm - 2:30pm One main, one side and *Andaz Iced Tea $26 One main, one side, one dessert and *Andaz Iced Tea $29 MAINS SIDES Auntie’s Laksa, tiger prawns, sh cake, vermicelli rice noodles Crispy Organic Cucumber Beef Brisket Noodle Soup, chilli oil, spring onion Double Boiled Soup of the Day Hong Kong Style Vegetables Char Kway Teow, Chinese sausage, tiger prawns, squid, sh cake Wok-fried French Beans Kung Pao Chicken, cashew nuts, mixed peppers, organic jasmine rice Seafood Organic Fried Rice, tiger prawns, squid, crab meat, egg *OUR SPECIALTY Steamed Atlantic Cod, Hong Kong style, organic jasmine rice Andaz Iced Tea Sweet and Sour Pork Belly, mixed peppers, celery, organic jasmine rice A refreshing cup of TWG Singapore Breakfast tea blended with a homemade Wok-fried Angus Beef, homemade black pepper sauce, organic jasmine rice pandan syrup for local twist. DESSERTS WINES & BEERS $8 NETT Almond Silken Tofu & Lychee Jelly Chardonnay, Somerton, Australia Chilled Mango Sago & Pomelo Sauvignon Blanc, Los Vascos, Chile Steamed Yam Paste with Coconut Cream & Gingko Nut Prosecco, Veneto, Italy, N.V Seasonal Sliced Fruit Platter Shiraz, Somerton, Australia Cabernet Sauvignon, Los Vascos, Chile Andaz Pils, Pilsner, Singapore COFFEE & TEA $6 Rainforest Alliance Coffee Heineken 0.0, Lager, Netherlands Americano, Cappuccino Tiger, Lager, Singapore Double Espresso, Espresso, Latte TWG Teas Earl Grey, English Breakfast, Sencha Singapore Breakfast, Moroccan Mint Tag @AndazSingapore to share your best dining experience -

Happy Dining in the Valley Tennis Clinic TERM 2 There’S Much More Than Ding Dings and Horse Racing to Hong Kong’S 3 January to 1 April 2017 Cheeriest Vale

food WINTER CAMPS & CLINICS ENROLLING NOW AT www.esf.org.hk INSPIRING FUTURES Open to ESF Sports ESF & Non ESF Winter Camps & Clinics Students ENROL ONLINE WINTER CAMPS & CLINICS 13 - 30 December 2016 ESF Sports will host a number of sports camps Multi Sports Camp - starts at age 2! and clinics across Hong Kong. With access to Basketball Clinic Catch a tram to some of Hong Kong’s top gourmet stops. top quality facilities and our expert team of Football Clinic coaches, your child will have fun while developing Netball Clinic sporting abilities! Gymnastics Clinic Happy dining in the valley Tennis Clinic TERM 2 There’s much more than ding dings and horse racing to Hong Kong’s 3 January to 1 April 2017 cheeriest vale. Kate Farr & Rachel Read sniff out Happy Valley’s tastiest The role and power of sport in the development of young eateries. children cannot be overestimated. ESF Sports deliver a whole range of fun, challenging and structured sports programmes Dim sum delights like spring rolls, har gau and char siu bao Spice it up designed to foster a love of sport that will last a lifetime. If you prefer siu mai to scones with your come perfectly executed without a hint of Can you take the heat? The Michelin-starred afternoon tea, then Dim Sum, The Art of MSG, making them suitable for the whole Golden Valley sits on the first floor of The • Basketball • Multi Sports Chinese Tidbits is for you. It has been based family. The restaurant is open weekdays from Emperor Hotel and with its traditional decor • Football • Gymnastics in the same spot for nearly 25 years and 11am-11pm, or 10.30am-11pm at weekends and relaxed ambience, makes a pleasant • Netball • Kung Fu everything about this yum cha joint - from its (closed daily between 4.30 and 6pm), but we change of pace compare to the usual rowdy art deco-inspired interior to the long queues recommend swerving the scrum by dining Chinese banquet restaurants. -

TWR Wedding Kit-2018-8-30

The first step to your Happily Ever After A genre-defining restaurant and bar housed in a beautifully-restored 1940s chapel, spread over 40,000 square feet of grounds. The White Rabbit serves a fresh take on both classic European comfort food and cocktails, aiming to deliver an impeccable dining experience without the stuffiness of a typical fine dining establishment. It is a place where time stands still and one feels naturally at ease; be it for a casual meal or a celebration of epic proportions. Whether it is to celebrate the arrival of a little one, the union of a couple or a means of thanking your key clients and colleagues, The White Rabbit makes for a one-of-a-kind venue, fully customizable to your individual needs. NON EXCLUSIVE RECEPTION Directional signage Complimentary parking 1x table with white table cloth Usage of birdcage for red packets 1x guestbook *Add-on canapes available SOLEMNIZATION 1 hour exclusive usage of The Rabbit Hole 1x table with white table cloth & fresh floral centrepiece 5x chairs with fresh floral mini bouquet Usage of ring holder Usage of Balmain black in pen for signing 20-30 guests chairs Usage of 2 wireless handheld microphones Usage of in-house speakers for march-in music DINING Non-exclusive usage of The White Rabbit 4 course set menu 3 hours free flow of soft drinks and juices Table numbers Individual guests name place cards Individual guests menu Add-on alcohol beverages available *Minimum 20 people, maximum 60 people EXCLUSIVE RECEPTION Directional signage Names on roadside signage Complimentary -

Secondary Education Certificate Level May 2017 Session

SEC11/1lce1.17m MATRICULATION AND SECONDARY EDUCATION CERTIFICATE EXAMINATIONS BOARD UNIVERSITY OF MALTA, MSIDA SECONDARY EDUCATION CERTIFICATE LEVEL MAY 2017 SESSION SUBJECT: English Language PAPER NUMBER: I – Part 1 – a) Listening Comprehension SESSION 1 DATE: 18th March 2017 EXAMINER’S PAPER INSTRUCTIONS TO EXAMINERS Preparation before the session: Familiarise yourself with the texts before reading them aloud and take note of the punctuation in order to make the texts sound as natural as possible. Check the footnotes for the pronunciation of certain words. Check with the candidates whether you can be heard clearly. Procedure during the session: (1) Tell the candidates: You are going to listen to TWO passages and answer questions on both of them on the sheet provided. You may answer the questions at any time during the session. First, you have THREE minutes to read the questions on Text A. Give the candidates three minutes to read the questions on Text A. Read Text A. (2) Tell the candidates: You have THREE minutes to continue working on the questions. Give the candidates three minutes to continue working on the questions. Read Text A for the second and last time. (3) Tell the candidates: You have THREE minutes to complete your answers. Give the candidates three minutes to complete their answers. (4) Tell the candidates: The THREE minutes are up. Kindly turn the page. You now have three minutes to read the questions on Text B. Give the candidates three minutes to read the questions on Text B. Read Text B. (5) Tell the candidates: You have THREE minutes to continue working on the questions. -

Wow) Programme Is One of CEDARS’S Flagship Programmes to Provide a Comprehensive Induction Programme for Incoming Non-Local Students

Dear Students, Weeks of Welcome (WoW) programme is one of CEDARS’s flagship programmes to provide a comprehensive induction programme for incoming non-local students. Students are free to choose from a series of activities. The activities, which are a mixture of fun, fact finding, visits and tours, aim to help the newly arrived students to settle down, induct into the local way and get to know about the new environment and people. The WoW programme will be held from 18 – 31 Aug 2020. Currently, we are looking for motivated student hosts who have strong interest in contributing to the success of WoW programme. Post A – Student Host for WoW tours/programmes (i) Responsibilities: To receive new non-local students by leading the following orientation tours and fun programmes: - Explore Hong Kong by a ride on Ferris Wheel and Star Ferry - Breakfast at Cha Chaan Teng - Afternoon tea at Cha Chaan Teng - Yum Cha –dim sum tasting - Peak Walk - Discover popular spots of student activities on campus (Campus tour) - Essential shopping at Sai Ying Pun - Visit to Victoria Park “hip” places in Causeway Bay - Street food at Sai Ying Pun - Visit to Flower Market and Fa Yuen Street - Local techno-geek shopping tour at Sham Shui Po - Visit to Choi Hung Estate - Visit to Tai Koo Shing - Visit to Stanley (ii) Requirements: HKU current students with fluent spoken English and Cantonese; good communication and interpersonal skills; active, sociable, friendly and have overseas experience and/or experience in working with people from diverse cultural background. Applicants should be familiar with the campus and HK environment and be able to lead the above tours independently. -

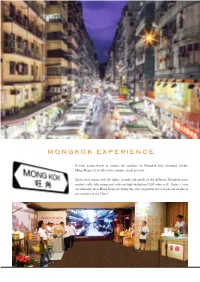

Mongkok Experience

MONGKOK EXPERIENCE If your group wants to explore the markets of Mongkok that surround Cordis, Hong Kong, let us offer you a unique sneak preview. Ignite your senses with the sights, sounds and smells of the different Mongkok street market stalls, fully integrated with our high definition LED video wall. Enjoy a taste of authentic, local Hong Kong by trying the city’s signature street food and snacks in the comfort of the Hotel. FRUIT MARKET & GOLDFISH CORNER The fruit market is packed with stalls and shops that sell exotic fruits from around the world. Smell a mixture of fruity fragrances and try our fresh fruit skewers made with seasonal tropical fruits. The goldfish market is loaded with rows of aquatic shops featuring CHA CHAAN TENG thousands of goldfish and other marine creatures. We have replicated this scene with colourful goldfish-shaped jelly treats These famous tea restaurants emerged during the 1980s when lining the walls of our Goldfish Corner. many Westerners migrated here, giving rise to a wide variety of Western versions of local food. Our Cha Chaan Teng stall serves local favorites such as egg tarts, Hong Kong-style milk tea and egg and ham toasties. EGG WAFFLE TROLLEY The Hong Kong egg waffle is a sweet egg based waffle MONGKOK EXPERIENCE with a crispy outer shell and soft chewy inside. It is one of Hong Kong’s most iconic and well loved street snacks – one not to be missed. FLOWER MARKET The flower market is an oasis full of stalls that sell all kinds of flowers and plants. -

Seasonal Summer Ice Cream & New Tropical Matcha Afternoon Tea At

Press Release For Immediate Release Hong Kong Meets Japan Sweet Summer Reviving Ice Cream & New Tropical Matcha Afternoon Tea at COCO 18 June 2020, Hong Kong: Staying cool while staying in the city is every summer’s challenge, this particular season more than ever. To help Hong Kong foodies deal with the mid-day heat, this July and August, stylish and ever-cool lobby café-patisserie COCO brings back its seasonal summer ice cream fiesta offering rewarding bowls of 3 creative ice cream combinations inspired with iconic local flavors and Japan’s favorite must- haves. Also, starting from July 1, COCO turns into a cool retreat from sweltering urban heat serving its fashionably refreshing afternoon tea presented on a triple-tier tea stand modelled after a handbag – a nod towards hotel’s location in Hong Kong’s shopping mecca – combining exotic, tropical fruit flavors and stimulating matcha into gorgeous desserts and finger foods including a trendy fruit sando. As an alternative and reviving “pick-me-up” to the 5 o’clock tea among the 3 new ice cream offerings is the Hong Kong’s local favorite Cha Chaan Teng featuring 3 scoops of ice cream: iconic milk tea flavor, coffee and crème brulee; with creative toppings of mini pineapple bun with a tiny slab of salted butter, golden-brown French toast, red bean, evaporated milk jelly and freshly baked mini Portuguese tart. Crowning the local foodie’s favorite combo is a hand-crafted chocolate can imitation of the recognizable sweetened condensed milk to crunch on. Transporting you to the instagrammable cafes of Kyoto and offering a medley of textures is COCO’s Matcha Madness with 3 scoops of rich green tea ice cream beautifully balanced with bouncy konjac jelly, matcha chocolate crispy rice, sweet and soft adzuki bean, spongy miniature matcha cream roll cake and crunchy ice cream cone topping the green overload combo smothered with green tea chocolate sauce. -

Fragrant Cooking Midnight

Simple Cooking ISSUE NO. 85 FIVE DOLLARS Cooking Midnight Uncooked, rice is called mai; cooked, it is fan. Once cooked, W rice was traditionally taken as food at least three times each day, first for jo chan, or early meal, either as congee or, if the weather was cool, cooked and served with a spoonful of liquid lard, soy sauce, and an egg. To eat rice is to sik fan, o and there is, in addition to those morning preparations, n’fan, or “afternoon rice,” and mon fan, or “evening rice.” There is even a custom called siu yeh, which translates K literally as “cooked midnight” and means rice eaten as a late evening snack. No time of any day in China is without its rice. —Eileen Yin-Fei Lo, THE CHINESE KITCHEN Fragrant LTHOUGH THERE’S NO EXACT EQUIVALENT, the closest we T WAS MY GRANDFATHER Who introduced me to the world come in this country to the casual everyday eat- of Chinese restaurants, at least as they were in the Aing experience of the Chinese is when we attend I1950s, beguilingly ersatz palaces spun of velvet and a country fair or something like one,where inexpensive, gold. As a teenager, I spent my summers with him, work- open-air food stalls abound and masses of people stroll ing at odd jobs at his apartment house in the daytime about, sampling from them as they go. Food courts aren’t and otherwise generally hanging around with him when really the same, because you go to these to eat, you buy I wasn’t off somewhere by myself. -

20 of the Best Food Tours Around the World

News Opinion Sport Culture Lifestyle Travel UK Europe US More Top 20s 20 of the best food tours around the world Feast your eyes on these foodie walking tours, which reveal the flavours – and culture – of cities from Lisbon to Lima, Havana to Hanoi The Guardian Wed 26 Jun 2019 14.19 BST EUROPE Porto Taste Porto’s tours are rooted in fundamental beliefs about the gastronomic scene in Portugal’s second city. First, Portuenses like to keep things simple: so, no fusion experiments. Second, it’s as much about the people behind the food, as the food itself. “Food is an expression of culture,” says US-born Carly Petracco, who founded Taste Porto in 2013 with her Porto-born husband Miguel and his childhood buddy André. “We like to show who’s doing the cooking, who’s serving the food, who’s supplying the ingredients, and so on.” She’s good to her word. Walking the city with one of the six guides feels less like venue-hopping and more like dropping in for a catch-up with a series of food-loving, old friends. Everywhere you go (whether it’s the Loja dos Pastéis de Chaves cafe with its flaky pastries or the Flor de Congregados sandwich bar with its sublime slow-roasted pork special) the experience is as convivial as it is culinary. And it’s not just food either. Taste Porto runs a Vintage Tour option that includes a final stop at boutique wine store, Touriga, where the owner David will willingly pair your palate to the perfect port.