Ambient Landscapes from Brian Eno to Tetsu Inoue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dave Matthews Band Away from the World Deluxe Rar

Dave Matthews Band Away From The World Deluxe Rar 1 / 4 Dave Matthews Band Away From The World Deluxe Rar 2 / 4 3 / 4 18 May 2018 ... Dave Matthews Band's violinist Boyd Tinsley has been sued for sexual assault, harassment, and “long-term ... But right now being away is better for him. ... Dave Matthews on His New Album, His Fans' Desires, and His Own Self-doubt ... Where Is My Sweatshirt of Ariana Grande Fingering the Earth?. (Rock) Dave Matthews Band - Come Tomorrow (2 CD) - 2018, MP3, 320 kbps 270.4 MB ... Dave Matthews Band - Away from the World (2012) Deluxe Edition .... Dave Matthews Band recorded Away From The World with Steve Lillywhite, who produced its first three studio records Under The Table And Dreaming, Crash .... Rhett Miller Announces New Solo Album + Old 97's Announce Holiday Album · Jim James Announces New Solo Album Uniform Clarity Out 10/5/18 .... Find Dave Matthews Band discography, albums and singles on AllMusic.. 21 Jul 2012 - 4 min - Uploaded by Jean LucDownload the Dave Matthews Band Away from the World Album here!! http:// www.mediafire .... The Best of What's Around Vol. 1, also known as TBOWA Vol. 1, is a greatest hits compilation album by the Dave Matthews Band that was ... Saturday, April 20, 1991 – the date of the band's first ever show, performed at the Earth Day ... Stand Up · Big Whiskey & the GrooGrux King · Away from the World · Come Tomorrow.. 4 Feb 2018 ... This special, uncirculated Dave Matthews solo acoustic ... College Dell, just before the release of the band's sophomore album Crash. -

Dream Askew Play

Dream Askew By Avery Alder The Overview Endlessly supported by Alea Milo Dream Askew gives us ruined buildings and wet tarps, nervous faces in the campire glow, strange new psychic powers, fierce queer love, and turbulent skies A game of belonging outside belonging above a fledgling community, asking “What do you do next?” Sigil by Ezra Rose Released 2018 Imagine that the collapse of civilization didn’t happen everywhere at the same time. Instead, it’s happening in waves. Every day, more people fall out of the Dream Askew was written on the unceded, ancestral territory of the Squamish, society intact. We queers were always living in the margins of that society, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh nations. finding solidarity, love, and meaning in the strangest of places. Apocalypse didn’t come for us first, but it did come for us. Gangs roam the apocalyptic wasteland, and scarcity is becoming the norm. The world is getting scarier, and just beyond our everyday perception, howling and hungry, there exists a psychic maelstrom. We banded together to form a queer enclave — a place to live, sleep, and hopefully heal. More than ever before, each of us is responsible for the survival and fate of our community. What lies in the rubble? For this close-knit group of queers, could it be utopia? Queer strife amid the collapse. Collaboratively generate an apocalyptic setting. Content warnings: violence, gangs, oppression, bigotry, queer sexuality. For 3-6 players across 3-4 hours. Dream Askew Welcome to The Enclave Circle 3-5 visuals an abandoned complex, -

The Effects of Background Music on Video Game Play Performance, Behavior and Experience in Extraverts and Introverts

THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Laura Levy In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Psychology in the School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology December 2015 Copyright © Laura Levy 2015 THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR, AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS Approved by: Dr. Richard Catrambone Advisor School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bruce Walker School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Maribeth Coleman Institute for People and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: 17 July 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the researchers and students that made Food for Thought possible as the wonderful research tool it is today. Special thanks to Rob Solomon, whose efforts to make the game function specifically for this project made it a success. Additionally, many thanks to Rob Skipworth, whose audio engineering expertise made the soundtrack of this study sound beautifully. I express appreciation to the Interactive Media Technology Center (IMTC) for the support of this research, and to my committee for their guidance in making it possible. Finally, I wish to express gratitude to my family for their constant support and quiet bemusement for my seemingly never-ending tenure in graduate school. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF -

Acdsee Proprint

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit N9.2419 lPE lPITClHl K.C., Mo. FREE ALL THE MUSE TI:AT FITS THE PITCH ISSUE NO. 10 JULY -AUGUST 1981 LeRoi, John CaIe, Stones, Blues, 3 Friends, Musso. Give the gift of music. OIfCharlie Parleer + PAGE 2 THE PENN:Y PITCH mJTU:li:~u-:~u"nU:lmmr;unmmmrnmmrnmmnunrnnlmnunPlIiunnunr'mlnll1urunnllmn broke. Their studio is above the Tomorrow studio. In conclusion, I l;'lish Wendy luck, because l~l~ lPIITC~1 I don't believe in legislating morals. Peace, love, dope, is from the Sex Machine a.k.a. (Dean, Dean) p.S. Put some more records in the $4.49 RELIGIOUS NAPOLEON group! 4128 BROADWAY KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64111 Dear Warren: (Dear Sex Machine: Titles are being added to (816) 561-1580 I recently came across something the $4.49 list each month. And at the Moon I thought you might "Religion light Madness Sale (July 17), these records is excellent stuff keeping common will be $3.99! Also, it's good to learn that people quiet." --Napoleon Bonaparte the spirit of t_he late Chet Huntley still can Editor ..............• Charles Chance, Jr. (1769-1821). Keep up the good work. cup of coffee, even one vibrated Assistant Editors ...•. Rev. Frizzell Howard Drake Jay '"lctHUO':V_L,LJLe Canyon, Texas LOVE FINDS LeROI Contributing Writers and Illustrators: (Dear Mr. Drake: I think Warren would Dear Warren: Milton Morris, Sid Musso, DaVINK, Julia join us in saying, "Religion is like This is really a letter to Donk, Richard Van Cleave, Jim poultry-- you gotta pluck it and fry it LeRoi. -

Russell-Mills-Credits1

Russell Mills 1) Bob Marley: Dreams of Freedom (Ambient Dub translations of Bob Marley in Dub) by Bill Laswell 1997 Island Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance, image melts: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings: Russell Mills 2) The Cocteau Twins: BBC Sessions 1999 Bella Union Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance and image melts: Michael Webster (storm) 3) Gavin Bryars: The Sinking Of The Titanic / Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet 1998 Virgin Records Art and design: Russell Mills Design assistance and image melts: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings and assemblages: Russell Mills 4) Gigi: Illuminated Audio 2003 Palm Pictures Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Photography: Jean Baptiste Mondino 5) Pharoah Sanders and Graham Haynes: With a Heartbeat - full digipak 2003 Gravity Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings and assemblages: Russell Mills 6) Hector Zazou: Songs From The Cold Seas 1995 Sony/Columbia Art and design: Russell Mills and Dave Coppenhall (mc2) Design assistance: Maggi Smith and Michael Webster 7) Hugo Largo: Mettle 1989 Land Records Art and design: Russell Mills Design assistance: Dave Coppenhall Photography: Adam Peacock 8) Lori Carson: The Finest Thing - digipak front and back 2004 Meta Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Photography: Lori Carson 9) Toru Takemitsu: Riverrun 1991 Virgin Classics Art & design: Russell Mills Cover -

Sonification As a Means to Generative Music Ian Baxter

Sonification as a means to generative music By: Ian Baxter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts & Humanities Department of Music January 2020 Abstract This thesis examines the use of sonification (the transformation of non-musical data into sound) as a means of creating generative music (algorithmic music which is evolving in real time and is of potentially infinite length). It consists of a portfolio of ten works where the possibilities of sonification as a strategy for creating generative works is examined. As well as exploring the viability of sonification as a compositional strategy toward infinite work, each work in the portfolio aims to explore the notion of how artistic coherency between data and resulting sound is achieved – rejecting the notion that sonification for artistic means leads to the arbitrary linking of data and sound. In the accompanying written commentary the definitions of sonification and generative music are considered, as both are somewhat contested terms requiring operationalisation to correctly contextualise my own work. Having arrived at these definitions each work in the portfolio is documented. For each work, the genesis of the work is considered, the technical composition and operation of the piece (a series of tutorial videos showing each work in operation supplements this section) and finally its position in the portfolio as a whole and relation to the research question is evaluated. The body of work is considered as a whole in relation to the notion of artistic coherency. This is separated into two main themes: the relationship between the underlying nature of the data and the compositional scheme and the coherency between the data and the soundworld generated by each piece. -

Informationen Als

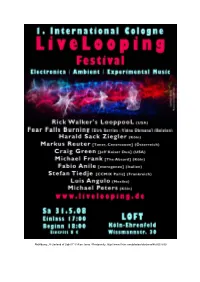

Abbildung: „A Garland of Light II“ © Alan Jaras / Reciprocity, http://www.flickr.com/photos/alanjaras/465037590 Pressemitteilung 1. Internationales Kölner LiveLooping - Festival 31. Mai 2008 im LOFT (Köln), Eintritt 8 Euro, Einlaß 17 Uhr, Beginn 18 Uhr Kontakt und Information: Michael Peters, [email protected], Tel. 02207-912144 Was ist denn „Livelooping“? Livelooping-Musiker sind meist Solo-Musiker, die digitale Loop-Geräte (im Prinzip Echogeräte mit u.U. sehr langer Laufzeit) benutzen, um sich selbst in Echtzeit zu „multiplizieren“, d.h. die live erzeugten Klänge zu wiederholen und zu komplexen Klangschichten aufzutürmen. Das können rhythmische Gebilde sein, aber auch dichte Wolken von Ambient-Klängen. Auch ganze Songstrukturen können live mit Loops aufgebaut und dann als Grundlage für Soli benutzt werden. Der erste Livelooper (damals noch mit Hilfe von Tonbandgeräten = Tape Loops) war der amerikanische Minimalist Terry Riley, der in den späten 60ern mit seinem psychedelischen Loop- Stück „A Rainbow in Curved Air“ und nächtelangen loop-basierten „All Night Flights“ weltbekannt wurde. Später brachte der Ambient-Musik-Erfinder Brian Eno, dessen erstes Ambient-Werk "Discreet Music" mit Tape Loops realisiert wurde, dem King-Crimson-Gitarristen Robert Fripp diese Technik bei. Fripp erzeugte dann in den späten 70ern mit seiner elektrischen Gitarre und seinem „Frippertronics“- Tonbandsystem ungewöhnliche Klanggebilde und machte die Möglichkeiten des Livelooping vor allem Gitarristen bewußt, die nach neuen musikalischen Wegen suchten. Seit den 80ern kann Livelooping mit Hilfe von analogen, später digitalen Loop-Delays erzeugt werden; es gibt mittlerweile eine reichhaltige Auswahl an einfachen und komplexen Loop-Geräten sowie an Software für das Livelooping aus dem Computer. Eine wachsende weltweite Community von Loop-Musikern diskutiert seit über 10 Jahren die technischen und musikalischen Aspekte des Livelooping auf der Loopers Delight-Internet-Mailingliste, und in Amerika, Europa und Japan finden regelmäßig Festivals für Loop-basierte Musik statt. -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

Roedelius Bio Engl

ROEDELIUS: JARDIN AU FOU CD and Vinyl Release date: March 27th 2009 Cat No BB23 CD 927892/LP 927891 The essentials: ► Hans-Joachim Roedelius: born 1934; first record release in 1969 with Kluster (with Dieter Moebius and Konrad Schnitzler), and active ever since as a solo artist and in various collaborations (amongst others with Moebius/Cluster, Moebius and Michael Rother/Harmonia, as well as with Brian Eno). One of the most prolific musicians of the German avant-garde and a key figure in the birth of Krautrock, synthesizer pop and ambient music. ► Jardin au Fou was first released on the French EGG label in 1979 ► produced by Peter Baumann (Tangerine Dream) ► liner notes by Asmus Tietchens ► CD features six bonus tracks: three remixes, three new tracks One of the most remarkable albums of the so-called Krautrock scene has to be Jardin au Fou by Hans-Joachim Roedelius (Cluster, Harmonia), issued in 1979. All the more noteworthy as it bore no resemblance whatsoever to what was expected of avant-garde electronica and displayed none of the typical Krautrock characteristics. Rhythm machine, sequencer and abstract sounds are conspicuous by their absence. Indeed, listeners were stunned by one of the most beautiful, charming, ethereal and peaceful albums in the history of German rock music. It was produced by Peter Baumann at his own Paragon Studios in 1978, a year after he left Tangerine Dream to concentrate on a solo career and production work. At the time, he was charged by the French label EGG with delivering three productions from the German electro/avant- garde/Krautrock cosmos. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Haruomi Hosono, Shigeru Suzuki, Tatsuro Yamashita

Haruomi Hosono Pacific mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Jazz Album: Pacific Country: Japan Released: 2013 Style: Fusion, Electro MP3 version RAR size: 1618 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1203 mb WMA version RAR size: 1396 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 218 Other Formats: AA ASF VQF APE AIFF WMA ADX Tracklist Hide Credits 最後の楽園 1 Bass, Keyboards – Haruomi HosonoDrums – Yukihiro TakahashiKeyboards – Ryuichi 4:03 SakamotoWritten-By – Haruomi Hosono コーラル・リーフ 2 3:45 Piano – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Shigeru Suzuki ノスタルジア・オブ・アイランド~パート1:バード・ウィンド/パート2:ウォーキング・オン・ザ・ビーチ 3 9:37 Keyboards – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Tatsuro Yamashita スラック・キー・ルンバ 4 Bass, Guitar, Percussion – Haruomi HosonoDrums – Yukihiro TakahashiKeyboards – Ryuichi 3:02 SakamotoWritten-By – Haruomi Hosono パッション・フラワー 5 3:35 Piano – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Shigeru Suzuki ノアノア 6 4:10 Piano – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Shigeru Suzuki キスカ 7 5:26 Written-By – Tatsuro Yamashita Cosmic Surfin' 8 Drums – Yukihiro TakahashiKeyboards – Haruomi Hosono, Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – 5:07 Haruomi Hosono Companies, etc. Record Company – Sony Music Direct (Japan) Inc. Credits Remastered By – Tetsuya Naitoh* Notes 2013 reissue. Album originally released in 1978. Track 8 is a rare early version of the Yellow Magic Orchestra track. Translated track titles: 01: The Last Paradise 02: Coral Reef 03: Nostalgia of Island (Part 1: Wind Bird, Part 2: Walking on the Beach 04: Slack Key Rumba 05: Passion Flower 06: Noanoa 07: Kiska Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4582290393407 -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period.