At the Wordface: J.R.R. Tolkien's Work on the Oxford English Dictionary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donald Ross – the Early Years in America

Donald Ross – The Early Years in America This is the second in a series of Newsletter articles about the life and career of Donald J. Ross, the man who designed the golf course for Monroe Golf Club in 1923. Ross is generally acknowledged as the first person to ever earn a living as a golf architect and is credited with the design of almost 400 golf courses in the United States and Canada. In April of 1899, at the age of 27, Donald Ross arrived in Boston from Dornoch, Scotland. This was not only his first trip to the United States; it was likely his first trip outside of Scotland. He arrived in the States with less than $2.00 in his pocket and with only the promise of a job as keeper of the green at Oakley Golf Club. Oakley was the new name for a course founded by a group of wealthy Bostonians who decided to remake an existing 11-hole course. Ross had been the greenkeeper at Dornoch Golf Club in Scotland and was hired to be the new superintendent, golf pro and to lay out a new course for Oakley. Situated on a hilltop overlooking Boston, Oakley Golf Club enjoys much the same type land as Monroe; a gently rising glacier moraine, very sandy soil and excellent drainage. Ross put all his experiences to work. With the help of a civil engineer and a surveyor, Ross proceeded to design a virtually new course. It was short, less than 6,000 yards, typical for courses of that era. -

The “Dirty Dozen” Tax Scams Plus 1

The “Dirty Dozen” Tax Scams Plus 1 Betty M. Thorne and Judson P. Stryker Stetson University DeLand, Florida, USA betty.thorne @stetson.edu [email protected] Executive Summary Tax scams, data breaches, and identity fraud impact consumers, financial institutions, large and small businesses, government agencies, and nearly everyone in the twenty-first century. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) annually issues its top 12 list of tax scams, known as the “dirty dozen tax scams.” The number one tax scam on the IRS 2014 list is the serious crime of identity theft. The 2014 list also includes telephone scams, phishing, false promises of “free money,” return preparer fraud, hiding income offshore, impersonation of charitable organizations, false income, expenses, or exemptions, frivolous arguments, false wage claims, abusive tax structures, misuse of trusts and identity theft. This paper discusses each of these scams and how taxpayers may be able to protect themselves from becoming a victim of tax fraud and other forms of identity fraud. An actual identity theft nightmare is included in this paper along with suggestions on how to recover from identity theft. Key Words: identity theft, identity fraud, tax fraud, scams, refund fraud, phishing Introduction Top Ten Lists and Dirty Dozen Lists have circulated for many years on various topics of local, national and international interest or concern. Some lists are for entertainment, such as David Letterman’s humorous “top 10 lists” on a variety of jovial subjects. They have given us an opportunity to smile and at times even made us laugh. Other “top ten lists” and “dirty dozen” lists address issues such as health and tax scams. -

1X Basic Properties of Number Words

NUMERICALS :COUNTING , MEASURING AND CLASSIFYING SUSAN ROTHSTEIN Bar-Ilan University 1x Basic properties of number words In this paper, I discuss three different semantic uses of numerical expressions. In their first use, numerical expressions are numerals, or names for numbers. They occur in direct counting situations (one, two, three… ) and in mathematical statements such as (1a). Numericals have a second predicative interpretation as numerical or cardinal adjectives, as in (1b). Some numericals have a third use as numerical classifiers as in (1c): (1) a. Six is bigger than two. b. Three girls, four boys, six cats. c. Hundreds of people gathered in the square. In part one, I review the two basic uses of numericals, as numerals and adjectives. Part two summarizes results from Rothstein 2009, which show that numericals are also used as numerals in measure constructions such as two kilos of flour. Part three discusses numerical classifiers. In parts two and three, we bring data from Modern Hebrew which support the syntactic structures and compositional analyses proposed. Finally we distinguish three varieties of pseudopartitive constructions, each with different interpretations of the numerical: In measure pseudopartitives such as three kilos of books , three is a numeral, in individuating pseudopartitives such as three boxes of books , three is a numerical adjective, and in numerical pseudopartitives such as hundreds of books, hundreds is a numerical classifier . 1.1 x Basic meanings for number word 1.1.1 x Number words are names for numbers Numericals occur bare as numerals in direct counting contexts in which we count objects (one, two, three ) and answer questions such as how many N are there? and in statements such as (1a) 527 528 Rothstein and (2). -

Organizing Knowledge: Comparative Structures of Intersubjectivity in Nineteenth-Century Historical Dictionaries

Organizing Knowledge: Comparative Structures of Intersubjectivity in Nineteenth-Century Historical Dictionaries Kelly M. Kistner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Gary G. Hamilton, Chair Steven Pfaff Katherine Stovel Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Sociology ©Copyright 2014 Kelly M. Kistner University of Washington Abstract Organizing Knowledge: Comparative Structures of Intersubjectivity in Nineteenth-Century Historical Dictionaries Kelly Kistner Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Gary G. Hamilton Sociology Between 1838 and 1857 language scholars throughout Europe were inspired to create a new kind of dictionary. Deemed historical dictionaries, their projects took an unprecedented leap in style and scale from earlier forms of lexicography. These lexicographers each sought to compile historical inventories of their national languages and were inspired by the new scientific approach of comparative philology. For them, this science promised a means to illuminate general processes of social change and variation, as well as the linguistic foundations for cultural and national unity. This study examines two such projects: The German Dictionary, Deutsches Worterbuch, of the Grimm Brothers, and what became the Oxford English Dictionary. Both works utilized collaborative models of large-scale, long-term production, yet the content of the dictionaries would differ in remarkable ways. The German dictionary would be characterized by its lack of definitions of meaning, its eclectic treatment of entries, rich analytical prose, and self- referential discourse; whereas the English dictionary would feature succinct, standardized, and impersonal entries. Using primary source materials, this research investigates why the dictionaries came to differ. -

Words of the World: a Global History of the Oxford English Dictionary

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540316 Words of the World Most people think of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as a distinctly British product. Begun in England 150 years ago, it took more than 60 years to complete, and when it was finally finished in 1928, the British prime minister heralded it as a ‘national treasure’. It maintained this image throughout the twentieth century, and in 2006 the English public voted it an ‘Icon of England’, alongside Marmite, Buckingham Palace, and the bowler hat. But this book shows that the dictionary is not as ‘British’ as we all thought. The linguist and lexicographer, Sarah Ogilvie, combines her insider knowledge and experience with impeccable research to show that the OED is in fact an international product in both its content and its making. She examines the policies and practices of the various editors, applies qualitative and quantitative analysis, and finds new OED archival materials in the form of letters, reports, and proofs. She demonstrates that the OED,in its use of readers from all over the world and its coverage of World English, is in fact a global text. sarah ogilvie is Director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre, Reader in Linguistics at the Australian National University, and Chief Editor of Oxford Dictionaries, Australia. -

The Early Years

HISTORY OF THE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIETY: THE EARLY YEARS BY FIONA MARSHALL University of Sheffield 1. THE ORIGINAL PHILOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON1 Formed in response to the new comparative philology practised by a handful of scholars on the Continent in the 1820s, the original Philological Society held the first in a series of informal meetings at London University in the early 1830s. Word of the new continental philology, established primarily by Rasmus Kristian Rask (1787- 1832), Franz Bopp (1791-1867), and Jacob (Ludwig Karl) Grimm (1785-1863), filtered through to London principally, though not exclusively, via Friedrich August Rosen (1805-1837), the first and only incumbent of a chair in Oriental Literature at London University (1828-31). Partly due to the heightened interest in comparative philology and partly in pursuit of the 'Philological Illustration of the Classical Writers of Greece and Rome' (PPS V, 1854: 61), Cambridge classicists Thomas Hewitt Key (1799-1875) and George Long (1800-1879), together with German-born Rosen, established the Society for Philological Inquiries (subsequently renamed the Philological Society) in 1830. With the addition of fellow Cambridge scholar Henry Malden (1800-1876) in 1831, the founding principles behind the original and succeeding Philological Society were established. The primary aims of the Society epitomised the growing and groundbreaking desire in early nineteenth-century British scholarship, not customary elsewhere, to combine the old (classical) philology with the new. Since few records remain in the archives, extant details about the original Society are vague. The whereabouts of the Society's manuscript minutes book, laid on the table by Key at a meeting of the present Society in 1851, are unknown (PPS V, 1854: 61). -

The Meaning of Everything: the History of the Oxford English Dictionary Transcript

The Meaning of Everything: The history of the Oxford English Dictionary Transcript Date: Monday, 9 March 2009 - 12:00AM A HISTORY OF THE DICTIONARY THE MEANING OF EVERYTHING: A HISTORY OF THE OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY Professor Charlotte Brewer I'm here today to talk to you about the Oxford English Dictionary, perhaps the most famous dictionary in the English-speaking world. Work on this great dictionary first began in the 1860s, and many people associate the OED in their minds with the days of Victorian Empire, when there was red all over the map of the world and England and the English language seemed at the centre of the world. So I shall start off my history of the OED with a brief sketch explaining this great dictionary in the context of its time: [slide 2] What was it? Why was it great? How was it made? By whom? But the OED is very much alive and kicking today: it is a living dictionary, and it is particularly alive at the moment, since it is part- way through a project of root-and branch revision which started in 2000 and is set to continue for quite a few decades yet - and this will be what I will come onto next. Then finally I want to think about that phrase in my title: the meaning of everything. In what sense is or was that true? What do we mean by everything? How does that fit in with the history of the OED? But let's begin by being clear what we mean when we refer to the Oxford English Dictionary. -

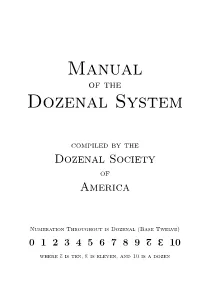

Manual Dozenal System

Manual of the Dozenal System compiled by the Dozenal Society of America Numeration Throughout is Dozenal (Base Twelve) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 XE 10 where X is ten, E is eleven, and 10 is a dozen Dozenal numeration is a system of thinking of numbers in twelves, rather than tens. Twelve is a much more versatile number, having four even divisors—2, 3, 4, and 6—as opposed to only two for ten. This means that such hatefulness as “0.333. ” for 1/3 and “0.1666. ” for 1/6 are things of the past, replaced by easy “0;4” (four twelfths) and “0;2” (two twelfths). In dozenal, counting goes “one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, elv, dozen; dozen one, dozen two, dozen three, dozen four, dozen five, dozen six, dozen seven, dozen eight, dozen nine, dozen ten, dozen elv, two dozen, two dozen one. ” It’s written as such: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X, E, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 1X, 1E, 20, 21. Dozenal counting is at once much more efficient and much easier than decimal counting, and takes only a little bit of time to get used to. Further information can be had from the dozenal societies, as well as in many other places on the Internet. The Dozenal Society of America http://www.dozenal.org The Dozenal Society of Great Britain http://www.dozenalsociety.org.uk © 1200 Donald P. Goodman III. All rights reserved. This document may be copied and distributed freely, subject to the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 United States License, available at http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/ 3.0/us/. -

Transparency Ratings for Spanishâ•Fienglish Cognate Words

Cognate Nouns Transparency Ratings for Spanish–English Cognate Words by José A. Montelongo, PhD California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California [email protected] (805)756-7492 Anita C. Hernández, PhD California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California [email protected] (805)756-5537 Roberta J, Herter, PhD California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California [email protected] (805)756-1568 Submitted to Cal Poly Digital Repository March 2, 2009 Running Head: Spanish-English Cognate Ratings 1 Cognate Nouns Transparency Ratings for Spanish–English Cognate Words Abstract Cognates are words that are orthographically, semantically, and syntactically similar in two languages. There are over 20,000 Spanish-English cognates in the Spanish and English languages. Empirical research has shown that cognates facilitate vocabulary acquisition and reading comprehension for language learners when compared to noncognate words. In this study, transparency ratings for over two thousand nouns and adjectives drawn from the Juilland and Chang-Rodríguez’ Spanish Word Frequency Dictionary were collected. The purpose for collecting the ratings was to provide researchers with calibrated materials to study the effects of cognate words on learning. 2 Cognate Nouns Transparency Ratings for Spanish–English Cognate Words An individual’s vocabulary is one of the best predictors of reading comprehension. In general, the larger an individual’s vocabulary, the better the comprehension. Fortunately for English Language Learners (ELLs) whose native language is Spanish, English and Spanish have in common more than 20,000 words that are orthographically, syntactically, and semantically equivalent. The usefulness of Spanish-English cognates is punctuated by the fact that these words are among the most frequently used in the English language (Johnston, 1941; Montelongo, 2002). -

Folio 2015 a Dozen Moons

A Dozen Moons by Richard Mack A Quiet Light Publishing Folio 2015 A Dozen Moons In our lifetimes we see 13 moons on average per year or 1,043 moons in 80 years. Yet how many do we really see? Whether because of weather just not looking up I am guessing it is a quarter of that number. Everyone comments when the moon is full and visible and beautiful. Noticed by you and your friends or family. But how many go unnoticed? I set out to shoot as many as I could over the years. Sadly not as many as I would have liked. But here are 12 moons which have caught my attention over the years. It takes planning to get a nice shot of the full moon. Do you want to be there the night before the full moon to get more daylight on the landscape? What do you want to feature in the foreground? Which perspective, distant with mostly landscape and a moon or a large moon dominating the image. It always amazes me that man has travelled to this place. Whenever I look at the moon I remember where I was the first time man stepped on that distant place. I was with 50,000 other folks at the Boy Scout National Jamboree watching it on jumbo screens with the backup astronauts for that mission telling us what was going on. Since then I have seen many moons pass overhead. Each one in a place I remember with fondness. From places where I was working on a book to places I happen to be. -

Principles for a Practical Moon Base T Brent Sherwood

Acta Astronautica 160 (2019) 116–124 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Acta Astronautica journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/actaastro Principles for a practical Moon base T Brent Sherwood Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, USA ABSTRACT NASA planning for the human space flight frontier is coming into alignment with the goals of other planetary-capable national space agencies and independent commercial actors. US Space Policy Directive 1 made this shift explicit: “the United States will lead the return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization”. The stage is now set for public and private American investment in a wide range of lunar activities. Assumptions about Moon base architectures and operations are likely to drive the invention of requirements that will in turn govern development of systems, commercial-services purchase agreements, and priorities for technology investment. Yet some fundamental architecture-shaping lessons already captured in the literature are not clearly being used as drivers, and remain absent from typical treatments of lunar base concepts. A prime example is general failure to recognize that most of the time (i.e., before and between intermittent human occupancy), a Moon base must be robotic: most of the activity, most of the time, must be implemented by robot agents rather than astronauts. This paper reviews key findings of a seminal robotic-base design-operations analysis commissioned by NASA in 1989. It discusses implications of these lessons for today's Moon Village and SPD-1 paradigms: exploration by multiple actors; public-private partnership development and operations; cislunar infrastructure; pro- duction-quantity exploitation of volatile resources near the poles to bootstrap further space activities; autonomy capability that was frontier in 1989 but now routine within terrestrial industry. -

The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration

The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration Edited by Joel S. Levine The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration Edited by Joel S. Levine This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Joel S. Levine and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6308-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6308-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................... x Joel S. Levine Remembrance. Brian J. O’Brien: From the Earth to the Moon ................ xvi Rick Chappell, Jim Burch, Patricia Reiff, and Jackie Reasoner Section One: The Apollo Experience and Preparing for the Artemis Missions Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 Measurements of Surface Moondust and Its Movement on the Apollo Missions: A Personal Journey Brian J. O’Brien Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 41 Lunar Dust and Its Impact on Human Exploration: Identifying the Problems