JNS 2 2020 Gustafssonreinius.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kevin Corstorphine

www.gothicnaturejournal.com Gothic Nature Gothic Nature 1 How to Cite: Corstorphine, K. (2019) ‘Don’t be a Zombie’: Deep Ecology and Zombie Misanthropy. Gothic Nature. 1, 54-77. Available from: https://gothicnaturejournal.com/. Published: 14 September 2019 Peer Review: All articles that appear in the Gothic Nature journal have been peer reviewed through a double-blind process. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Gothic Nature is a peer-reviewed open access journal. www.gothicnaturejournal.com ‘Don’t be a Zombie’: Deep Ecology and Zombie Misanthropy Kevin Corstorphine ABSTRACT This article examines the ways in which the Gothic imagination has been used to convey the message of environmentalism, looking specifically at attempts to curb population growth, such as the video ‘Zombie Overpopulation’, produced by Population Matters, and the history of such thought, from Thomas Malthus onwards. Through an analysis of horror fiction, including the writing of the notoriously misanthropic H. P. Lovecraft, it questions if it is possible to develop an aesthetics and attitude of environmental conservation that does not have to resort to a Gothic vision of fear and loathing of humankind. It draws on the ideas of Timothy Morton, particularly Dark Ecology (2016), to contend with the very real possibility of falling into nihilism and hopelessness in the face of the destruction of the natural world, and the liability of the human race, despite individual efforts towards co-existence. -

Philosophical Fables for Ecological Thinking: Resisting Environmental Catastrophe Within the Anthropocene

Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy, Kingston School of Art, Kingston University Philosophical Fables for Ecological Thinking: Resisting Environmental Catastrophe within the Anthropocene Alice GIBSON Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy February 2020 2 Abstract This central premise of this thesis is that philosophical fables can be used to address the challenges that have not been adequately accounted for in post-Kantian philosophy that have contributed to environmental precarity, which we only have a narrow window of opportunity to learn to appreciate and respond to. Demonstrating that fables may bring to philosophy the means to cultivate the wisdom that Immanuel Kant described as crucial for the development of judgement in the Critique of Pure Reason (1781), I argue that the philosophical fable marks an underutilised resource at our disposal, which requires both acknowledgment and defining. Philosophical fables, I argue, can act as ‘go-carts of judgement’, preventing us from entrenching damaging patterns that helped degree paved the way for us to find ourselves in a state of wholescale environmental crisis, through failing adequately to consider the multifarious effects of anthropogenic change. This work uses the theme of ‘catastrophe’, applied to ecological thinking and environmental crises, to examine and compare two thinker poets, Giacomo Leopardi and Donna Haraway, both of whom use fables to undertake philosophical critique. It will address a gap in scholarship, which has failed to adequately consider how fables might inform philosophy, as reflected in the lack of definition of the ‘philosophical fable’. This is compounded by the difficulty theorists have found in agreeing on a definition of the fable in the more general sense. -

Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Warming and Acidification of the Oceans from Capitalocene, Chthulucene,” in Donna J

We are all lichens. – Scott Gilbert, “We Are All Lichens Now”1 Think we must. We must think. – Stengers and Despret, Women Who Make 01/17 a Fuss2 What happens when human exceptionalism and bounded individualism, those old saws of Western philosophy and political economics, become unthinkable in the best sciences, whether natural or social? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with. Biological sciences Donna Haraway have been especially potent in fermenting notions about all the mortal inhabitants of the Earth since the imperializing eighteenth century. Tentacular Homo sapiens – the Human as species, the Anthropos as the human species,Modern Man – Thinking: was a chief product of these knowledge practices. What happens when the best biologies Anthropocene, of the twenty-first century cannot do their job with bounded individuals plus contexts, when organisms plus environments, or genes plus Capitalocene, whatever they need, no longer sustain the overflowing richness of biological knowledges, if Chthulucene they ever did? What happens when organisms plus environments can hardly be remembered for the same reasons that even Western-indebted people can no longer figure themselves as individuals and societies of individuals in e n human-only histories? Surely such a e c transformative time on Earth must not be named u l u the Anthropocene! h y t a h ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊWith all the unfaithful offspring of the sky C w , a r e gods, with my littermates who find a rich wallow a n e H c in multispecies muddles, I want to make a a o n l a n critical and joyful fuss about these matters. -

Feminist Speculative Futures

FEMINIST SPECULATIVE FUTURES Imagination, and the Search for Alternatives in the Anthropocene Mavi Irmak Karademirler Media, Art, and Performance Studies Student Number: 6489249 Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Ingrid Hoofd Second Reader: Dr. Dan Hassler-Forest 1 Thesis Statement The ongoing social and ecological crises have brought many people together around an urgent quest to search for other kinds of possibilities for the future, imagination and fiction seem to play a key role in these searches. The thesis engages the concept of imagination by considering it in relation to feminist SF, which stands for science fact, science fiction, speculative fabulation, string figures, so far. (Haraway, 2013) The thesis will engage the ideas of feminist SF with a focus on the works of Donna Haraway and Ursula Le Guin, and their approaches to the capacity of imagination in the context of SF practices. It considers the role of imagination and feminist speculative fiction in challenging and converting prevalent ideas of human-exceptionalism entangled with dominant forms of Man-made narratives and storylines. This conversion through feminist SF leans towards ecological, nondualist modes of thinking that question possibilities for a collective flourishing while aiming to go beyond the anthropocentric and cynical discourse of the Anthropocene. Cultural experiences address the audience's imagination, and evoke different modes of thinking and sensing the world. The thesis will outline imagination as a sociocultural, relational capacity, and it will work together with the theoretical perspectives of feminist SF to elaborate upon how cultural experiences can extend the audience’s imagination to enable envisioning other worlds, and relate to other forms of subjectivities. -

Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene

CHAPTER 2 Tentacular Thinking Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene We are all lichens. —Scott Gilbert, “We Are All Lichens Now” Think we must. We must think. —Stengers and Despret, Women Who Make a Fuss What happens when human exceptionalism and bounded individualism, those old saws of Western philosophy and political economics, become unthinkable in the best sciences, whether natural or social? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with. Biological sciences have been especially potent in fermenting notions about all the mortal inhabi- tants of the earth since the imperializing eighteenth century. Homo sapiens—the Human as species, the Anthropos as the human species, Modern Man—was a chief product of these knowledge practices. What happens when the best biologies of the twenty-first century cannot do their job with bounded individuals plus contexts, when organisms plus environments, or genes plus whatever they need, no longer sustain the overflowing richness of biological knowledges, if they ever did? What happens when organisms plus environments can hardly be remembered for the same reasons that even Western-indebted people can no longer Copyright © 2016. Duke University Press. All rights reserved. Press. All rights © 2016. Duke University Copyright figure themselves as individuals and societies of individuals in human- Haraway, Donna J.. <i>Staying with the Trouble : Making Kin in the Chthulucene</i>, Duke University Press, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=4649739. Created from unimelb on 2019-07-18 19:20:00. only histories? Surely such a transformative time on earth must not be named the Anthropocene! In this chapter, with all the unfaithful offspring of the sky gods, with my littermates who find a rich wallow in multispecies muddles, I want to make a critical and joyful fuss about these matters. -

Staying with the Trouble of Our Ongoing Epoch

CHAPTER 2 Tentacular Thinking Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene We are all lichens. —Scott Gilbert, “We Are All Lichens Now” Think we must. We must think. —Stengers and Despret, Women Who Make a Fuss What happens when human exceptionalism and bounded individualism, those old saws of Western philosophy and political economics, become unthinkable in the best sciences, whether natural or social? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with. Biological sciences have been especially potent in fermenting notions about all the mortal inhabi- tants of the earth since the imperializing eighteenth century. Homo sapiens—the Human as species, the Anthropos as the human species, Modern Man—was a chief product of these knowledge practices. What happens when the best biologies of the twenty-frst century cannot do their job with bounded individuals plus contexts, when organisms plus environments, or genes plus whatever they need, no longer sustain the overfowing richness of biological knowledges, if they ever did? What happens when organisms plus environments can hardly be remembered for the same reasons that even Western-indebted people can no longer fgure themselves as individuals and societies of individuals in human- only histories? Surely such a transformative time on earth must not be named the Anthropocene! In this chapter, with all the unfaithful ofspring of the sky gods, with my littermates who fnd a rich wallow in multispecies muddles, I want to make a critical and joyful fuss about these matters. I want to stay with the trouble, and the only way I know to do that is in generative joy, terror, and collective thinking. -

A Generous and Troubled Chthulucene: Contemplating Indigenous and Tranimal Relations in (Un)Settled Worldings Sebastian De Line

A Generous and Troubled Chthulucene: Contemplating Indigenous and Tranimal Relations in (Un)settled Worldings Sebastian De Line ABSTRACT: This article is an analysis of key topics in Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble: Making Kinship in the Chthulucene. By following the game rules of the two string figures, cat’s cradle (non-Indigenous) and na’atl’o’ (Din’eh), the article weighs from Indigenous perspectives the political and ontological implica- tions of such multispecies storytelling. Through its diffractive close reading, this paper puts in conversation Indigenous and non-Indigenous concepts and authors: Deleuzian rhizomatic deterritorialization and Indigenous self-determinacy, para- digmatic All My/Our Relations of Winona LaDuke, Leroy Little Bear, and Gregory Cajete, and the spider pimoa cthulhu. The aim is to recognize the multiplicity of forms of kinships or dependencies and to consider what kind of implications they have on marginalized assemblages. While Haraway suggests to call our contemporary planetary condition the Chthu- lucene, an epoch that requires from us to rethink relationality and co-existence, this paper looks at how the animacy of the world and the relationality of nonhu- man and human animals in it create circumstances for “tranimals to emerge.” By giving ethical consideration to our material animacy, tranimacy will serve us as a tool to analyse the entanglement of nonhuman and human animals, trans materi- ality, and questions relating to agency. KEYWORDS: Chthulucene, Indigeneity, Trans, tranimality, diffraction, animacy, re- lationality, assemblage. AUTHOR NOTE: Sebastian De Line is a trans artist and scholar of Haudenosaunee- European-Asian descent. He holds an M.A. (Art Praxis) from the Dutch Art Institute Graduate Journal of Social Science Sept. -

Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulhucene Donna Haraway in Conversation with Martha Kenney

Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulhucene Donna Haraway in conversation with Martha Kenney Since long before the recent interest in the Anthropocene, Donna Haraway has been concerned with the question of how to live well “on a vulnerable planet that is not yet murdered.”1 One of our most vital thinkers on the poli- tics of nature and culture (which she believes cannot and should not be sep- arated), Haraway’s writing bristles with generosity, outrage, wit, and fierce intelligence. She has inspired generations of readers to think critically and creatively about how to live and work inside the difficult legacies of settler colonialism, industrial capitalism, and militarized technoscience. This work of inheriting violent pasts and presents in the process of building more liveable worlds, Haraway argues, must be understood as a collective project composed of connections that are only partial, fraught with contra- dictions, disagreements, and refusals—and made up of mundane practices that are nevertheless consequential. She models this approach in her own writing, where she thinks with and through the work of fellow feminists, artists, activists, science fiction writers, biologists, and critters of all kinds. As this interview demonstrates, Haraway’s citation practice is interdisciplinary, multi-generational, and exuberant. She cites her own PhD advisor, ecolo- gist G. Evelyn Hutchinson, as well as her former students Astrid Schrader, Eva Hayward, and Natalie Loveless. For Haraway, thinking, writing, and world-making are always the work of sym-poiesis, of making together. These days, Haraway is committed to “staying with the trouble” in multispe- cies worlds where suffering and flourishing are unevenly distributed and always at stake. -

1Jonathas De Andrade, •2Isabelle Andriessen

Przewodnik | Exhibition Guide WIEK PÓŁCIENIA Sztuka w czasach planetarnej zmiany WIOSNA 2020 THE PENUMBRAL AGE. Art in the Time of Planetary Change SPRING 2020 •1Jonathas de Andrade, •2Isabelle Andriessen, •3Rasheed Araeen, •4Robert Barry, •5Kasper Bosmans, •6 Boyle Family, •7Agnieszka 9 788364 177651 Brzeżańska, •8Dora Budor, •9Vija Celmins, •10Center for Land Use Interpretation, •11Alice Creischer, •12Czekalska + Golec, •13 Betsy Damon, •14 Tacita Dean, •15 Thierry De Cordier, •16Agnes Denes, •17Ines Doujak, •18Jimmie Durham, •19Jerzy Fedorowicz, •20Hamish Fulton, •21Futurefarmers, •22 Cyprien Gaillard, •23Simryn Gill, •24 Wanda Gołkowska, •25Guerrilla Girls, •26Małgorzata Gurowska, •27Anna & Lawrence Halprin, •28Mitsutoshi Hanaga, •29 Suzanne Husky, •30Ice Stupa Project, •31INTERPRT, •32Anja Kanngieser, •33 Karrabing Film Collective, •34Beom Kim, •35Frans Krajcberg, •36 Susanne Kriemann, •37Stefan Krygier, •38Katalin Ladik, •39Nicolás Lamas, •40John Latham, •41Richard Long, •42Antje Majewski, •43Nicholas Mangan, •44Krzysztof Maniak, •45Qavavau Manumie, •46Robert Morris, •47Shana Moulton & Nick Hallett, •48 Teresa Murak, •49Peter Nadin & Natsuko Uchino & Aimée Toledano, •50Bruce Nauman, •51Nishiko,•52Isamu Noguchi, •53OHO, •54Dennis Oppenheim, •55Prabhakar Pachpute & Rupali Patil, •56Maria Pinińska-Bereś, •57Agnieszka Polska, •58Joanna Rajkowska, •59Jerzy Rosołowicz, •60Oscar Santillán, •61Gerry Schum, •62Bonnie Ora Sherk, •63Anna Siekierska, •64Rudolf Sikora, •65Magdalena Starska, •66Irv Teibel, •67Akira Tsuboi, •68Maria Waśko, Ryszard Waśko, •69Lawrence Weiner, •70Magdalena Więcek, •71Andrea Zittel wiekpolcienia.artmuseum.pl THE PENUMBRAL AGE. Art in the Time of Planetary Change THE PENUMBRAL AGE. Art in the Time of Planetary Change Aby In order to żyć w świecie, który nie have lived in a month where ociepla się z miesiąca na mie- the world was not warming month siąc, trzeba było urodzić się w roku by month, you need to have been born 1985 lub wcześniej. -

Arctic Traces

The Journal of Northern Studies is a peer-reviewed academic publication issued twice a year. The journal has a specific focus on human activities in northern spaces, and articles concentrate on people as cultural beings, people in society and the interaction between people and the northern environment. In many cases, the contributions represent exciting interdisciplinary and multidis- ciplinary approaches. Apart from scholarly artic- les, the journal contains a review section, and a section with reports and information on issues relevant for Northern Studies. The journal is published by Umeå University and Sweden’s northernmost Royal Academy, the Royal Skyttean Society. ISSN 1654–5915 Vol. 14 • No. 2 • 2020 Published by Umeå University & The Royal Skyttean Society Umeå 2021 The Journal of Northern Studies is published with support from The Royal Skyttean Society and Umeå University at www.jns.org.umu.se For instructions to authors, see www.jns.org.umu.se © The authors and Journal of Northern Studies ISSN 1654-5915 Cover picture Scandinavia Satellite and sensor: NOAA, AVHRR Level above earth: 840 km Image supplied by METRIA, a division of Lantmäteriet, Sweden. www.metria.se NOAAR. cESA/Eurimage 2001. cMetria Satellus 2001 Design and layout Leena Hortéll, Ord & Co i Umeå AB Fonts: Berling Nova and Futura Contents Editors & Editorial board ..........................................................................................................................................6 Lotten Gustafsson Reinius, Special Issue. Tracing the Arctic; Arctic Traces ...............................................7 Articles Kirsten Hastrup, Living (with) Ice. Geo-sociality in the High Arctic .......................................................25 Martin Jakobsson, The Long Timeline of the Ice. A Geological Perspective on the Arctic Ocean ...............................................................................................................................................................42 Kyrre Kverndokk, The Age of Climate Change. -

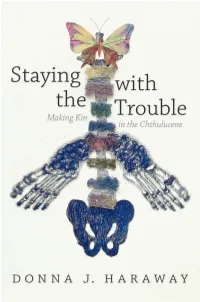

Donna J. Haraway

Staying with the Trouble Making Kin in the Chthulucene Donna J. Haraway duke university press durham and london 2016 CHAPTER 2 Tentacular Thinking Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene We are all lichens. —Scott Gilbert, “We Are All Lichens Now” Think we must. We must think. —Stengers and Despret, Women Who Make a Fuss What happens when human exceptionalism and bounded individualism, those old saws of Western philosophy and political economics, become unthinkable in the best sciences, whether natural or social? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with. Biological sciences have been especially potent in fermenting notions about all the mortal inhabi- tants of the earth since the imperializing eighteenth century. Homo sapiens—the Human as species, the Anthropos as the human species, Modern Man—was a chief product of these knowledge practices. What happens when the best biologies of the twenty-frst century cannot do their job with bounded individuals plus contexts, when organisms plus environments, or genes plus whatever they need, no longer sustain the overfowing richness of biological knowledges, if they ever did? What happens when organisms plus environments can hardly be remembered for the same reasons that even Western-indebted people can no longer fgure themselves as individuals and societies of individuals in human- only histories? Surely such a transformative time on earth must not be named the Anthropocene! In this chapter, with all the unfaithful ofspring of the sky gods, with my littermates who fnd a rich wallow in multispecies muddles, I want to make a critical and joyful fuss about these matters. I want to stay with the trouble, and the only way I know to do that is in generative joy, terror, and collective thinking. -

DOKTORA TEZİ (3.336Mb)

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature English Language and Literature REPRESENTATIONS OF THE ANTHROPOCENE FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY: RICHARD JEFFERIES’S AFTER LONDON, OR WILD ENGLAND, DORIS LESSING’S MARA AND DANN: AN ADVENTURE AND ADAM NEVILL’S LOST GIRL Kübra BAYSAL Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2019 REPRESENTATIONS OF THE ANTHROPOCENE FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY: RICHARD JEFFERIES’S AFTER LONDON, OR WILD ENGLAND, DORIS LESSING’S MARA AND DANN: AN ADVENTURE AND ADAM NEVILL’S LOST GIRL Kübra BAYSAL Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature English Language and Literature Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2019 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has been born of a hard, ardent but equally fruitful Ph.D. journey during which I had countless mind-opening courses from most respected professors of the Department of English Language and Literature at Hacettepe University that shaped the academic path of my life since the first day I started my university adventure. Getting to test my intellectual as well as bodily limits and learning that there is no end to acquiring knowledge, I have opened my eyes and mind to the realities of the world that readily find a place in the fictional worlds of literary works, namely novels, which explains how the inspiration for this dissertation came to me. Within this context, I want to express my first heartfelt gratitude to my thesis supervisor, Prof. Dr. Aytül ÖZÜM, whose strong academic profile has put me in the right track in my doctoral endeavour, for harnessing this inspiration and leading the way in a most professional way all throughout the writing phase of this dissertation with her sincere, warm, direct and constantly positive attitude along with her valuable scholarly advice.