The 2014 JINSA Generals and Admirals Program in Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strateg Ic a Ssessmen T

Strategic Assessment Assessment Strategic Volume 19 | No. 4 | January 2017 Volume 19 Volume The Prime Minister and “Smart Power”: The Role of the Israeli Prime Minister in the 21st Century Yair Lapid The Israeli-Palestinian Political Process: Back to the Process Approach | No. 4 No. Udi Dekel and Emma Petrack Who’s Afraid of BDS? Economic and Academic Boycotts and the Threat to Israel | January 2017 Amit Efrati Israel’s Warming Ties with Regional Powers: Is Turkey Next? Ari Heistein Hezbollah as an Army Yiftah S. Shapir The Modi Government’s Policy on Israel: The Rhetoric and Reality of De-hyphenation Vinay Kaura India-Israel Relations: Perceptions and Prospects Manoj Kumar The Trump Effect in Eastern Europe: Heightened Risks of NATO-Russia Miscalculations Sarah Fainberg Negotiating Global Nuclear Disarmament: Between “Fairness” and Strategic Realities Emily B. Landau and Ephraim Asculai Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 19 | No. 4 | January 2017 Abstracts | 3 The Prime Minister and “Smart Power”: The Role of the Israeli Prime Minister in the 21st Century | 9 Yair Lapid The Israeli-Palestinian Political Process: Back to the Process Approach | 29 Udi Dekel and Emma Petrack Who’s Afraid of BDS? Economic and Academic Boycotts and the Threat to Israel | 43 Amit Efrati Israel’s Warming Ties with Regional Powers: Is Turkey Next? | 57 Ari Heistein Hezbollah as an Army | 67 Yiftah S. Shapir The Modi Government’s Policy on Israel: The Rhetoric and Reality of De-hyphenation | 79 Vinay Kaura India-Israel Relations: Perceptions and Prospects | 93 Manoj Kumar The Trump Effect in Eastern Europe: Heightened Risks of NATO-Russia Miscalculations | 103 Sarah Fainberg Negotiating Global Nuclear Disarmament: Between “Fairness” and Strategic Realities | 117 Emily B. -

Politics in Troubled Times: Israel-Turkey Relations

Politics in Troubled Times: Israel-Turkey Relations FOREIGN POLICY PROGRAMME Mensur Akgün, Sabiha Senyücel Gündoğar & Aybars Görgülü INTRODUCTION: relations between the two countries. If the adversarial relations between Israel and Turkey Israel-Turkey relations, which strained once again are mended and bilateral dialogue is improved, recently due to frequent crises, continue to be a this could in turn strengthen Turkey’s capacity to major issue on Turkey’s foreign policy agenda. tackle regional problems. Over the past five years, the positive relations between Turkey and Israel in political, economic, Setting out with the premise that the current military and social spheres have deteriorated situation of Israel-Turkey relations is detrimental to all parties in the region, which is considerably. Given the military operation of already lacking in stability, as TESEV Foreign Israel into the Gaza Strip in July 2014, which Policy Program, we have conducted a series of resulted in more than 2000 Palestinian studies in order to dwell upon alternative areas casualties, the normalization of relations and the of cooperation and discuss the current state of restoration of the previous partnership between relations. To this end, we organized two the two countries seem unlikely in the near roundtable meetings: the first one was held on 2 future. However, since both countries continue to October 2013 in Istanbul and the second was play significant roles in the region, there is a organized in Jerusalem on 22 December 2013. visible need to establish a platform for further These meetings brought together politicians, Turkish-Israeli cooperation and dialogue. journalists, academics, civil society After the foundation of Israel as an independent representatives and experts from Turkey and state, Israel-Turkey relations have generally Israel. -

2014 Gaza War Assessment: the New Face of Conflict

2014 Gaza War Assessment: The New Face of Conflict A report by the JINSA-commissioned Gaza Conflict Task Force March 2015 — Task Force Members, Advisors, and JINSA Staff — Task Force Members* General Charles Wald, USAF (ret.), Task Force Chair Former Deputy Commander of United States European Command Lieutenant General William B. Caldwell IV, USA (ret.) Former Commander, U.S. Army North Lieutenant General Richard Natonski, USMC (ret.) Former Commander of U.S. Marine Corps Forces Command Major General Rick Devereaux, USAF (ret.) Former Director of Operational Planning, Policy, and Strategy - Headquarters Air Force Major General Mike Jones, USA (ret.) Former Chief of Staff, U.S. Central Command * Previous organizational affiliation shown for identification purposes only; no endorsement by the organization implied. Advisors Professor Eliot Cohen Professor of Strategic Studies, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Corn, USA (ret.) Presidential Research Professor of Law, South Texas College of Law, Houston JINSA Staff Dr. Michael Makovsky Chief Executive Officer Dr. Benjamin Runkle Director of Programs Jonathan Ruhe Associate Director, Gemunder Center for Defense and Strategy Maayan Roitfarb Programs Associate Ashton Kunkle Gemunder Center Research Assistant . — Table of Contents — 2014 GAZA WAR ASSESSMENT: Executive Summary I. Introduction 7 II. Overview of 2014 Gaza War 8 A. Background B. Causes of Conflict C. Strategies and Concepts of Operations D. Summary of Events -

Just Below the Surface: Israel, the Arab Gulf States and the Limits of Cooperation

Middle East Centre JUST BELOW THE SURFACE ISRAEL, THE ARAB GULF STATES AND THE LIMITS OF COOPERATION IAN BLACK LSE Middle East Centre Report | March 2019 About the Middle East Centre The Middle East Centre builds on LSE’s long engagement with the Middle East and provides a central hub for the wide range of research on the region carried out at LSE. The Middle East Centre aims to enhance understanding and develop rigorous research on the societies, economies, polities and international relations of the region. The Centre promotes both special- ised knowledge and public understanding of this crucial area, and has outstanding strengths in interdisciplinary research and in regional expertise. As one of the world’s leading social science institutions, LSE comprises departments covering all branches of the social sciences. The Middle East Centre harnesses this expertise to promote innova- tive research and training on the region. Middle East Centre Just Below the Surface: Israel, the Arab Gulf States and the Limits of Cooperation Ian Black LSE Middle East Centre Report March 2019 About the Author Ian Black is a former Middle East editor, diplomatic editor and European editor for the Guardian newspaper. He is currently Visiting Senior Fellow at the LSE Middle East Centre. His latest book is entitled Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917–2017. Abstract For over a decade Israel has been strengthening links with Arab Gulf states with which it has no diplomatic relations. Evidence of a convergence of Israel’s stra- tegic views with those of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain has accumulated as all displayed hostility to Iran’s regional ambitions and to United States President Barack Obama’s policies during the Arab Spring. -

Iran's Evolving Maritime Presence

PolicyWatch 2224 Iran's Evolving Maritime Presence Michael Eisenstadt and Alon Paz اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ Also available in March 13, 2014 The growing capabilities of Iran's navy will enhance the country's soft power and its peacetime reach, while providing an alternative means of supplying the "axis of resistance" if traditional means of civilian transport become untenable. On March 6, Israeli naval forces in the Red Sea seized a Panamanian-flagged vessel, the Klos C , carrying arms -- including long-range Syrian-made M-302 rockets -- destined for Palestinian militants in Gaza. The month before, a two-ship Iranian naval flotilla set out on a much advertised cruise that would, it is claimed, for the first time take Iranian ships around Africa and into the Atlantic Ocean. These two events illustrate the role maritime activities play in Iran's growing ability to project influence far from its shores, and how the Iranian navy has emerged, in the words of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, as a "strategic force" on the high seas. The Growing Importance of the Maritime Arena Iran's naval forces -- like the rest of its armed forces -- are divided into two organizations: the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGCN) and the Islamic Republic of Iran Navy (IRIN). The IRGCN's combat fleet consists of hundreds of small boats, several dozen torpedo boats and fast-attack craft armed with antiship missiles, and a number of midget submarines. These forces are trained and organized for naval unconventional warfare and access-denial missions in the Persian Gulf. The IRIN's combat fleet consists of a half dozen obsolete frigates, a dozen missile-equipped patrol boats, a number of midget submarines, and three large diesel submarines that operate outside the Gulf in support of Iran's maritime access-denial strategy. -

Why Israel Is Quietly Cosying up to Gulf Monarchies | World News | the Guardian

9/26/2019 Why Israel is quietly cosying up to Gulf monarchies | World news | The Guardian Why Israel is quietly cosying up to Gulf monarchies After decades of hostility, a shared hatred of Iran and a mutual fondness for Trump is bringing Israel’s secret links with Gulf kingdoms out into the open. By Ian Black Main image: Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu with the Sultan of Oman, Qaboos bin Said Al Said, in Muscat in October 2018. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images Tue 19 Mar 2019 06.00 GMT n mid-February 2019, Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, flew to Warsaw for a highly unusual conference. Under the auspices of the US vice-president, Mike Pence, he met the foreign ministers of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and two other Gulf states that have no diplomatic relations with Israel. The main item on the agenda was containing Iran. No Palestinians were present. Most of the existing links between Israel and the Gulf have been kept secret – but these talks were not. In fact, Netanyahu’s office leaked a video of a closed session, Iembarrassing the Arab participants. The meeting publicly showcased the remarkable fact that Israel, as Netanyahu was so keen to advertise, is winning acceptance of a sort from the wealthiest countries in the Arab world – even as the prospects for resolving the longstanding Palestinian issue are at an all-time low. This unprecedented rapprochement has been driven mainly by a shared animosity towards Iran, and by the disruptive new policies of Donald Trump. Hostility to Israel has been a defining feature of the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East since Israel’s creation in 1948 and the expulsion or flight of more than 700,000 Palestinians – which Arabs call the Nakba, or catastrophe – that accompanied it. -

Israel's Air and Missile Defense During the 2014 Gaza

Israel’s Air and Missile Defense During the 2014 Gaza War Rubin Uzi Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 111 www.besacenter.org THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 111 Israel’s Air and Missile Defense During the 2014 Gaza War Uzi Rubin Israel’s Air and Missile Defense During the 2014 Gaza War Uzi Rubin © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel Tel. 972-3-5318959 Fax. 972-3-5359195 [email protected] http://www.besacenter.org ISSN 1565-9895 February 2015 Cover picture: Flickr/Israel Defense Forces The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies advances a realist, conservative, and Zionist agenda in the search for security and peace for Israel. It was named in memory of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, whose efforts in pursuing peace lay the cornerstone for conflict resolution in the Middle East. The center conducts policy-relevant research on strategic subjects, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel and Middle East regional affairs. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author’s views or conclusions. Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center for the academic, military, official and general publics. -

Filling in the Blanks

Filling in the Blanks Documenting Missing Dimensions in UN and NGO Investigations of the Gaza Conflict A publication of NGO Monitor and UN Watch Edited by Gerald M. Steinberg and Anne Herzberg Filling in the Blanks Documenting Missing Dimensions in UN and NGO Investigations of the Gaza Conflict Filling in the Blanks Documenting Missing Dimensions in UN and NGO Investigations of the Gaza Conflict A publication of NGO Monitor and UN Watch Edited by Gerald M. Steinberg and Anne Herzberg Contributors Gerald Steinberg Hillel Neuer Jonathan Schanzer Abraham Bell Dr. Uzi Rubin Trevor Norwitz Anne Herzberg Col. Richard Kemp Table of Contents Preface i. Executive Summary 1 Chapter 1: Production and Import of Rockets and Missiles Launched from Gaza at Targets in Israel 6 Chapter 2: The Sources of Hamas Financing, and the Implications Related to Providing Assistance to a Recognized Terror Organization 27 Chapter 3: Evidence Regarding the Abuse of Humanitarian Aid to Gaza for Military and Terror Purposes, and Questions of Supervision and Accountability 41 Chapter 4: The Credibility of Reports and Allegations from Non- Governmental Organizations (NGOs) Regarding the 2014 Conflict 73 Appendix 1: Submission to the United Nations Independent Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict by Colonel Richard Kemp CBE 131 Appendix 2: Letter to Mary McGowan Davis, Chair of United Nations Independent Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict by Trevor S. Norwitz 144 Appendix 3: Why the Schabas Report Will Be Every Bit as Biased as the Goldstone Report by Hillel Neuer (originally published in The Tower, March 2015, reprinted with permission) 149 Appendix 4: Letter to Ban Ki-Moon, Secretary General of the United Nations by Prof Gerald Steinberg 161 Contributors and Acknowledgements 163 Endnotes: 168 Filling in the Blanks i Preface his report provides an independent, fully-sourced, systematic, and detailed documentation on some of the key issues related to the renewal of intense conflict between Hamas and Israel during July and August 2014. -

IMS EXECUTIVE PROGRAM @ Israel

IMS EXECUTIVE PROGRAM @ Israel < THE START-UP NATION> INTRODUCTORY PACKET | MARCH 30TH - APRIL 5TH, 2019 THIS PACKET CONTAINS: the Start-Up 1. PREPARATION MATERIALS Nation 2. PROGRAM LOGISTICS 3. PROGRAM GOALS & OBJECTIVES - 4. AGENDA We are extremely excited to have you join us 5. IMS + SPEAKER BIOS for what promises to be a very unique program experience! IMS’s Program at Israel 6. ABOUT THE VISITS will be held on March 30th- April 5th, 2019. Please come prepared to learn and discuss real-world examples of how startups are rapidly influencing the way we innovate and lead in our organizations. program We’re excited for you to start your journey through the Start-up nation in just a few weeks. As a next step, we’d like you to take a moment to go through the pre-work material. This ensures that you have relevant resources to start thinking about the start-up nation. Let’s briefly review why Israel is frequently called a “Startup Nation” through the following materials: Videos Start-up nation Articles How Israel Became a Startup Nation GO TO ARTICLE GO TO VIDEO Why is Israel called a start-up nation? Secret Behind the Success of Israeli Startups GO TO VIDEO GO TO ARTICLE Israeli technology is everywhere 5 Charts That Explain Israeli Startup Success GO TO VIDEO GO TO ARTICLE Israeli Startups Raised Record Capital in 2018 GO TO ARTICLE What’s Next for Israeli Startups? GO TO ARTICLE Accommodations IMS Team: MARKETING HEAD Ignacio Zinny +1 (917) 587-0010 [email protected] MARKETING MANAGER Nicole Bebchik Hilton Tel Aviv Mamilla Jerusalem +1 (305) 332-8363 HaYarkon St 205, Tel Aviv-Yafo, 6340506 Shlomo Ha-Melekh 11 st, Jerusalem, 94182 [email protected] IMS Executive Program @ Israel Israel, a country with a population of around 8.5M, has earned the moniker of “Startup Nation” mostly because it has the largest number of start-ups per capita in the world, around 1 startup for every 1,400 people. -

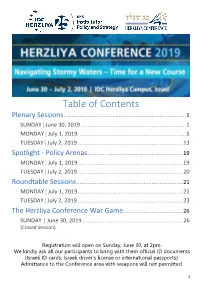

Conference Program

Table of Contents Plenary Sessions .............................................................................. 1 SUNDAY | June 30, 2019 ................................................................... 1 MONDAY | July 1, 2019 ..................................................................... 5 TUESDAY | July 2, 2019 ................................................................... 13 Spotlight - Policy Arenas ............................................................. 19 MONDAY | July 1, 2019 ................................................................... 19 TUESDAY | July 2, 2019 ................................................................... 20 Roundtable Sessions .................................................................... 21 MONDAY | July 1, 2019 ................................................................... 21 TUESDAY | July 2, 2019 ................................................................... 23 The Herzliya Conference War Game ...................................... 26 SUNDAY | June 30, 2019 ................................................................ 26 (Closed Session) Registration will open on Sunday, June 30, at 2pm. We kindly ask all our participants to bring with them official ID documents (Israeli ID cards, Israeli driver’s license or international passports). Admittance to the Conference area with weapons will not permitted. 1 Plenary Sessions SUNDAY | June 30, 2019 14:00 Welcome & Registration 15:00 Opening Ceremony Prof. Uriel Reichman, President & Founder, IDC Herzliya Prof. -

Israel and the Middle East News Update

Israel and the Middle East News Update Tuesday, January 19 Headlines: Ambassador Shapiro: Settlements Threaten Two-State Solution Israeli Chief of Staff Eizenkot: Iran Deal Is an Opportunity Pregnant Israeli Woman Stabbed in West Bank Attack Reacting to Otniel Killing, Abbas Says He Opposes Violence Bennett: Israel’s Defense Thinking Is Deadlocked While Enemies Improving U.S. Officials in Israel Next Week to Finalize New Military Package EU Softens Policy, But Lays Line Between Israel, Settlements Rivlin: The Islamic State Is Already Here, Within Israel Commentary: Ma’ariv: “Former Mossad Chief Pardo: There Is No Existential Threat to Israel” By Yossi Melman, Israeli Journalist Specializing in Security, Intelligence Affairs Yedioth Ahronoth: “Message from the White House” By Shimon Shiffer, Senior Commentator, Yedioth Ahronoth S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace 633 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20004 www.centerpeace.org ● Yoni Komorov, Editor ● David Abreu, Associate Editor News Excerpts January 19, 2015 Ma’ariv Ambassador Shapiro: Settlements Threaten Two-State Solution US Ambassador to Israel Daniel Shapiro warned Israel that it would jeopardize the possibility of separation from the Palestinians if it were to continue to expand the settlements. Speaking at a conference of the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) in Tel Aviv, Shapiro criticized the fact that Israeli authorities did not deal vigorously with acts of violence against Palestinians, and said that at times there seemed to be two standards of adherence to the rule of law in the West Bank: one for Israelis and another for Palestinians. See also, “Shaked to U.S. Envoy: Recant Claim Israel Applies Separate Laws to Jews, Arabs” (Jerusalem Post) Ynet News Israeli Chief of Staff Eizenkot: Iran Deal Is an Opportunity IDF Chief of Staff Gadi Eizenkot on Monday touched on a range of security issues affecting Israel, during his speech at a convention taking place at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv. -

The 2014 Gaza War: the War Israel Did Not Want and the Disaster It Averted

The Gaza War 2014: The War Israel Did Not Want and the Disaster It Averted Hirsh Goodman and Dore Gold, eds. with Lenny Ben-David, Alan Baker, David Benjamin, Jonathan D. Halevi, and Daniel Rubenstein Front Cover Photo: Hamas fires rockets from densely populated Gaza City into Israel on July 15, 2014. The power plant in the Israeli city of Ashkelon is visible in the background. (AFP/Thomas Coex) Back Cover Photo: Hamas terrorists deploy inside a tunnel under the Gaza City neighborhood of Shuja’iya on Aug. 17, 2014. (Anadolu Images/Mustafa Hassona) © 2015 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 13 Tel Hai Street, Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 972-2-561-9281 Fax. 972-2-561-9112 Email: [email protected] www.jcpa.org Graphic Design: Darren Goldstein ISBN: 978-965-218-125-1 Contents Executive Summary 4 Preface 5 Israel’s Narrative – An Overview 7 Hirsh Goodman Telling the Truth about the 2014 Gaza War 31 Ambassador Dore Gold Israel, Gaza and Humanitarian Law: Efforts to Limit Civilian Casualties 45 Lt. Col. (res.) David Benjamin The Legal War: Hamas’ Crimes against Humanity and Israel’s Right to Self-Defense 61 Ambassador Alan Baker The Limits of the Diplomatic Arena 77 Ambassador Dore Gold Hamas’ Strategy Revealed 89 Lt. Col. (ret.) Jonathan D. Halevi Hamas’ Order of Battle: Weapons, Training, and Targets 109 Lenny Ben-David Hamas’ Tunnel Network: A Massacre in the Making 119 Daniel Rubenstein Hamas’ Silent Partners 131 Lenny Ben-David Gazan Casualties: How Many and Who They Were 141 Lenny Ben-David Key Moments in a 50-Day War: A Timeline 153 Daniel Rubenstein About the Authors 167 About the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 168 3 Executive Summary The Gaza War 2014: The War Israel Did Not Want and the Disaster It Averted is a researched and documented narrative that relates the truth as it happened.