Workers in the Field of Corrections Will Find in This Consultant's Paper In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Transcriot of Proceedingg,,VFD

Official Transcriot of Proceedingg,,VFD Before the “’ 23 8 43 ijn 97 %E’~~;,-‘Qr;:1&::I ,i. I’c,,,I1 UNITED STATES POSTAL RATE COMMISSIOPtf ScCH’%~ Ln the Matter of: POSTAL RATE AND FEE CHANGES Docket N~o. R97-1 VOLUME 13 DATE: Wednesday, October 22, 1997 PLACE: Washington, D.C. PAGES: 6708 -’ 7343 ANN RILEY & ASSOCIATES, LTD. 12501 St., N.W.,Suitc300 Washington,D.C. 2000.5 (202)842-0034 6708 1 BEFORE THE 2 POSTAL RATE COMMISSION 3 ___________-__ - x 4 In the Matter of: 5 POSTAL RATE AND FEE CHANGES : Docket No. R97-1 6 --------_-_____ X 7 8 Third Floor Hearing Room 9 Postal Rate Commission 10 1333 H Street, N.W. 11 Washington, D.C. 20268 12 13 Volume 13 14 Wednesday, October 22, 1997 15 16 The above-entitled matter came on for hearing, d 7 pursuant to notice, at 9:30 a.m. 18 19 BEFORE: 20 HON. EDWARDJ. GLEIMAN, CHAIRMAN 21 HON. GEORGE W. HALEY, VICE CHAIRMAN 22 HON. W. H. "TREY" LeBLANC, III, COMMISSIONER 23 HON. GEORGE A. OMAS, COMMISSIONER 24 HON. H. EDWARDQUICK, JR., COMMISSIONER 25 ANN RILEY & ASSOCIATES, LTD. Court Reporters 1250 I Street, N.W., Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 842-0034 6709 1 APPEARANCES: 2 On behalf of the Newspaper Association of America: 3 WILLIAM B. BAKER, ESQUIRE 4 ALAN R. JENKINS, ESQUIRE 5 MICHAEL YOURSHAW, ESQUIRE 6 Wiley, Rein & Fielding 7 1776 K Street, NW 8 Washington, DC 20006 9 (202) 429-7255 10 fax (202) 429-7049 11 12 ROBERT J. -

Collection of Television Press Kits, 1958, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c87082fc No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of television press kits, 1958, ca. 1974-ca. 2004 Finding aid prepared by Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 1908 1 television press kits, 1958, ca. 1974-ca. 2004 Title: Collection of television press kits Collection number: 1908 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 9.5 linear ft.(19 boxes and 1 flat box.) Date (inclusive): 1958, ca. 1974-2004 Abstract: This collections documents a variety of television show genres broadcast on networks such as ABC, CBS, NBC, HBO, PBS, SHOWTIME, and TNT. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the caollection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Mayor Proposes Suing County for Ownership of Causeway

*.i^***** CAR-RT SORT **P.OO3 u-r. ,0001006409 THU O00OO0 WIFCL LIBRARY OUNLOP RD ' BEL. FL 33937 L Firekittens page 13 Week of May 22-28,2003 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 30, NUMBER 21, 24 PAGES 75 CENTS Ii Til MEM Mayor proposes suing county Pro football in Southwest Fla. for ownership of Causeway Firecats play at Teco By Kate Thompson Staff writer —See page 13 Mayor Steve Brown will ask the City Council June 3 to put a referen- dum before voters on whether to bring a law- suit against Lee County for ownership of the causeway. Commissioner "Unless we have reacts ownership, we can hope to have input... but with Janes responds to mayor's 6,000 votes versus proposal 440,000, it's pretty straightforward," said Brown —See page 2 Brown. "I feel very, very strongly that we have to support that (the cause- way) stays the way it is and that our island stays the way it is." His remarks drew applause from a number of the people attending Tuesday's City Council Plover and meeting, but Brown himself stopped them, noting the council's strict civility rules that prohibit any mosquitos Kate Thompson photo Motorists cross the Causeway. At Tuesday's City Council meeting, Mayor Steve Brown pro- See CAUSEWAY Profiles of two flying posed a referendum on whether or not the city should sue over control of the Causeway. page 2 critters ;—See page 23 12 Baskets takes leftover food for charities By Amy Fleming There are people who shake Some years ago, Wood was about the "12 Baskets" program. -

Title: 1000 Airplanes on the Roof in - FOB and and Other Plays / COL Author: Hwang, David Henry Glass, Philip Publisher: New American Library 1990

Title: 1000 Airplanes on the Roof in - FOB and and Other Plays / COL Author: Hwang, David Henry Glass, Philip Publisher: New American Library 1990 Description: roy music-drama - monologue all male cast; one character one male four parts A science-fiction music-drama realized by Philip Glass, David Henry Hwang, and Jerome Sirlin. A 90-minute monologue. Title: 15 Seconds Author: Archambault, Francois translated by Bobby Theodore Publisher: Talonbooks 1998 Description: roy comedy four characters three male; one female one act Brimming with a dark and brittle humour, FIFTEEN SECONDS is a play about a young female advertising copy writer, her pro-sports-fan ex-boyfriend, a Gen-X welfare-bum loser and his brother handicapped by cerebral palsy. These four characters are constantly making choices about reality and illusion; imagination and fantasy; the hale and the handicapped - about the way things are and the way they might be. They are utterly unable to imagine each other, and though they all remember that they should try to do so, they seem to have forgotten from where this moral Title: 24 Favorite One Act Plays Author: Publisher: Doubleday 1958 Description: collection - drama includes: 27 Wagons Full of Cotton - Tennessee Williams Spreading the News - Lady Gregory A Marriage Proposal - Anton Chekhov In the Shadow of the Glen - J. M. Synge Cathleen ni Houlihan - W.B. Yeats The Jest of Hahalaba - Lord Dunsany Trifles - Susan Glaspell The Happy Journey - Thornton Wilder The Ugly Duckling - A.A. Milne Title: 2B (or not 2B) in - Laugh Lines: Short Comic Plays / COL Author: Reingold, Jacquelyn Publisher: Vintage Books 2007 Description: roy comedy two characters one male; one female one act suggested for high school. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers in Bessemer

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; BLACKISH) -

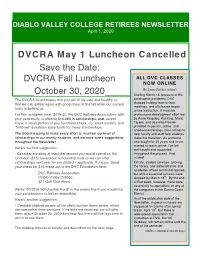

DVCRA Fall Luncheon October 30, 2020

DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE RETIREES NEWSLETTERIn this issue: April 1, 2020 DVCRA May 1 Luncheon Cancelled Save the Date: DVCRA Fall Luncheon ALL DVC CLASSES NOW ONLINE By Laury Fischer (editor) October 30, 2020 Starting March 16, because of the The DVCRA Board hopes that you will all be safe and healthy so coronavirus pandemic, DVC that we can gather again with good cheer in the fall when our current stopped holding face-to-face meetings, and all classes began crisis is behind us. online instruction. A massive For this academic year, 2019-20, the DVC Retirees Association, with professional development effort led your generosity, is offering $14,000 in scholarships, and, as you by Anne Kingsley, Kat King, Mario know, a small portion of your luncheon check, our silent auction, and Tejada, and Jeanette Peavler provided in-person, online, and “fishbowl” donations raise funds for these scholarships. one-to-one trainings (also online) to The Board is going to make every effort to maintain our level of help faculty and staff help students scholarships to our worthy students, and we have some suggestions make the transition. As someone throughout the Newsletter. who taught for 45 years and never wanted to teach online, I’ve felt Here’s our first suggestion: well-taught and supported • Consider donating at least the amount you would spend on the throughout the process. And luncheon ($15) toward our scholarship fund so we can offer scared. scholarships next year for our 2020-21 applicants. It’s easy: Send Initially, student services, tutoring, your check for $15 made out to the DVC Foundation here: the library, and administrative and academic offices remained opened, DVC Retirees Association but all but essential services were Diablo Valley College stopped by March 18th. -

3 1984-01-16 MUSIC WAS BORN in AFRICA/MOTHER AFRICA Babsy Mlangeni EMI EMI 1136 4 1984-01-16 DANCING in the DARK/BACK STREET

3 1984-01-16 MUSIC WAS BORN IN AFRICA/MOTHER AFRICA Babsy Mlangeni EMI EMI 1136 4 1984-01-16 DANCING IN THE DARK/BACK STREET DRIVER Kim Wilde EMI RAK 1143 5 1984-01-16 BREAK THE CHAINS/YOU’VE GOT TO WIN Private Lives EMI EMI 1155 6 1984-01-16 REMEMBER THE NIGHTS/KILLING TIME The Motels EMI CP 1163 7 1984-01-16 PIPES OF PEACE/SO BAD Paul McCartney EMI A 1167 8 1984-01-16 NOTHING TO DO WITH LOVE/(YOU ARE) THE ONE The Honeymoon EMI EMI 1176 9 1984-01-16 NEW MOON ON MONDAY/TIGER TIGER Duran Duran EMI EMI 1186 10 1984-01-16 POLITICS OF DANCING/CRUEL WORLD Re-Flex EMI EMI 1182 11 1984-01-16 RADIO GA GA/I GO CRAZY Queen EMI EMI 1184 12 1984-01-16 ON THE MOUNTAIN/EMMA John David EMI LS 1140 13 1984-01-16 LIVING IN AN ISLAND/FUNKY MONKEY MIA Bahloo EMI MIA 1168 14 1984-01-16 CAN’T TAKE LOVE FOR GRANTED/PASSIVE RESISTANCE Graham Parker EMI LS 1165 27 1984-01-16 THE SOUND OF GOODBYE/TAKE ME HOME Crystal Gayle WEA 729452 28 1984-01-16 IF I HAD YOU BACK/THE MAGIC’S BACK The Rubinoos WEA 729507 29 1984-01-16 ADDICTED TO THE NIGHT (2 versions)/CHOIR PRACTICE Lipps Inc. POL 812 900-1 30 1984-01-16 RELAX/FERRY CROSS THE MERSEY/RELAX Frankie Goes To Hollywood FES X 13139 31 1984-01-16 THE LIFEBOAT PARTY/GINA GINA/THERE’S SOMETHING WRONG IN Kid Creole & The Coconuts FES X 13136 PARADISE 32 1984-01-16 VICTIMS/COLOUR BY NUMBERS/ROMANCE REVISITED Culture Club CBS VS 64112 33 1984-01-16 THE LOVE CATS/SPEAK MY LANGUAGE/MR. -

Calendar History 1996 January 20

Calendar History 1996 January 20 - 22: CTTD NATPE Sales Meeting - Las Vegas 23 - 25: NATPE Convention in Las Vegas February March 18 & 19: CTTD: Mad About You Advisory Board, Loews Santa Monica April 6: CTT: Married...With Children Season Wrap, Malibu Castle North Hollywood 13-17: CTTD: NAB in Las Vegas May 16: CTTD: Ricki Lake Season Wrap, New York City 20 - June 4: CTIT May Screenings in Los Angeles 28: CTIT May Screenings Party - Century Club, LA June 4-9: CTIT Sales Meeting in Santa Barbara 19-21: CTTD/CTIT: PROMAX Convention at Los Angeles Convention Center July 28 - Aug. 2: CTTD Sales Meeting in Santa Barbara August September October 7 - 11: CTIT - MIPCOM Convention in France November December TBD: CTT: Married...With Children Holiday Party, Rita Hayworth TBD: CTTD: Ricki Lake Holiday Wrap in New York City 1997 January 11-13: CTTD NATPE Sales Meeting - New Orleans 13: CTIT NATPE Sales Meeting - New Orleans 14 - 16: NATPE Convention in New Orleans February 8: CTTD Bowling Party at Sports Center Bowl in Studio City March 3-5: CTIT Executive Retreat at Rancho Valencia 6: CTIT Bowling Party at Bay Shore Bowl in Santa Monica 25: CTTD: Devil’s Own Screening at Rita Hayworth/Backstage Theatre 28: CTT: Married...With Children Season Wrap Party at Dublins, West Hollywood April 4-10: CTTD: NAB in Las Vegas 6: CTT: Mad About You Season Wrap Party at Alto Palato 9-16: CTIT - MIP-TV in Cannes 16: CTT: Vibe/KCOP Cocktail Reception in Rita Hayworth Dining Room 24: CTT: Nanny 100th Press Event on the Set May 9: CTT: Early Edition Season Wrap Party -

Bay Stopover for Governor State Takes Ermergency Camdaiqnina Action to Revise Voting Instructions on Sept

CAR-RT SORT **F003 A SAN1D£.L t_ i ERARY 776*-, DUMl CP f D SAN I BEL FL 33957 •«"'•! Court page 2 _y Week of Aug. 8-14, 2002 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 29, NUMBER 31, 20 PAGES 75 CENTS II TIE IE1S Vote! . By Erik Burriss city attorney's demand for immediate vesting ney failed to produce a compromise. Deadline to register to vote Staff Writer or change party affiliation in a pension plan. "It was a pretty short meeting," Harrity said for Sept. 10 primary — During contract negotiations in • June, of Friday's one-on-one session in a report The portability of the city attorney's pen- 5 p.m. Aug. 12. Wyckoff said he would look for another job if Tuesday to the rest of the council. sion plan was rendered moot Tuesday when he did not receive immediate vesting. In a July He then read into the record a letter from City Council voted 3-2 to sack Doug Wyckoff. 30 memo to the council, Wyckoff again Wyckoff to council members in which The move came after continued disagree- Island spirit demanded a portable plan.' Wyckoff said he had no intention of resigning. ment over the terms of Wyckoff's employ- A last-ditch meeting late last week between ment, with the council refusing to accede to the Councilman Marty Harrity and the city attor- See COUNCIL Volunteerism — a culture page 9 of serving —See page 3 Primary change Bay stopover for governor State takes ermergency CamDaiqnina action to revise voting instructions on Sept. -

USDOT Region V Regional University Transportation Center Final Report

MN WI MI OH IL IN USDOT Region V Regional University Transportation Center Final Report NEXTRANS Project No. 120OSU2.1 TRUCK ACTIVITY AND WAIT TIMES AT INTERNATIONAL BORDER CROSSINGS by Mark R. McCord, Professor The Ohio State University [email protected] Colin N. Brooks, Senior Research Scientist Michigan Tech Research Institute [email protected] David Banach, Assistant Research Scientist Michigan Tech Research Institute [email protected] Report Submission Date November 30, 2016 MN WI MI OH IL IN USDOT Region V Regional University Transportation Center Final Report TECHNICAL SUMMARY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLAIMER Funding for this research was provided by the NEXTRANS Center, Purdue University under Grant No. DTRT12‐G‐UTC05 of the U.S. Department of Transportation, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST‐R), University Transportation Centers Program. Additional funding was provided by the Ohio State University’s (OSU) College of Engineering Transportation Research Endowment Program, the OSU Department of Civil, Environmental, and Geodetic Engineering, and the Michigan Tech Research Institute. The investigators gratefully acknowledge the support of Ray Cossette (CEVA Logistics) and Kirk Pettit (formerly, CEVA Logistics), as well as the technical assistance of Prem Goel, Nicole Sell, and Jiaqi Zaetz (formerly OSU), Jake Carr (ODU), Michael Billmire, Amanda Grimm, and Karl Bosse (Michigan Tech Research Institute). The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation, University Transportation Centers Program, in the interest of information exchange. -

Angry with City Code

•.••'ay-' ""•'' Week of Oct. 10-16, 2002 SANIBEL&CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 29, NUMBER 40, 20 PAGES 75 CENTS II Til NEWS ART ECO A SIGN OF PLANETARY TIMES East Rocks Ei Planning Commission • Denial likely on requested variance. angry with • Sweet sell —See page 2 city code Q A 'Ding' day By Erik Burriss National Wildlife Staff Writer Refuge Week, Oct. 12 The Sanibel Planning Commission —See page 3 will wait for a legal opinion on existing city codes about nuisances before mak- •3 Goss on tour ing any recommendations to City Council about possible unkempt lawn Southwest Florida legislation. students get insider's Spurred by a nearby yard that went view of Washington. unmowed for half a year, several East Rocks' residents urged the city to put —See page 3 Dawn deBoer photo something in place to allow the Police Department or Code Enforcement to Renowned eco-minded artists Clyde Butcher, above, and Luc Century, below, put their art to work do something about similar situations for the environment this week. Century's Calusa Art Project was in place for the Florida Museum in the future. CITV«60UNTY of Natural History's grand opening Saturday in Gainesville. Butcher and his latest exhibit of large- The discussion started off with a 60- format, black-and-white photographs of Florida landscapes made a duo appearance Tuesday at the slide photo essay of various landscap- 0 Leeway cut South Florida Water Management District's center in Fort Myers in behalf of restoring the ing options from Commissioner Marie Everglades. (See story and photos, page 19.) Gargano. -

December 21, 2020

December 21, 2020 As members of the Writers Guild of America, East, we stand with our fellow members at The Onion, Deadspin, The A/V Club, and The Takeout as they bargain their contract which expires December 31, 2020. As union members working in the film and television industry, we have seen time and again how solidarity wins real gains for working people, and we support our fellow members at The Onion brands as they work to build on the strong provisions in their existing contract. As they show their commitment to their co-workers, their work, and to the brands that they have built and love, we stand with them in solidarity. Signed, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) Doug Abeles (SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE; BUNK; WHO WANTS TO BE A MILLIONAIRE; EXPLORER TALK SHOW) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Demi Adejuyigbe (THE GOOD PLACE; THE LATE LATE SHOW WITH JAMES CORDEN; THE AMBER RUFFIN SHOW) Carlin Adelson (CUDDLING WITH CARLIN) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Marisol Adler (FALLING WATER) Jermaine Affonso (LATE NIGHT WITH SETH MEYERS) Subhah Agarwal (THE JIM JEFFRIES SHOW) Tom Agna (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; THE CHRIS ROCK SHOW;) Zachary Akers (EMERALD) Ozzie Alfonso (3-2-1 CONTACT) Lucy Alibar (BEASTS OF THE SOUTHERN WILD) Suzanne Allain (A THOUSAND MILES TO FREEDOM) 1 Leo Allen (SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE; NATHAN FOR YOU; IT'S PERSONAL WITH AMY HOGGART) Desireena Almoradie (NJ HEALTHCARE WORKERS ALLIANCE 2019 BUDGET CAMPAIGN) Shelly Altman (ONE LIFE TO LIVE;