A Chronicle of the Professional Life of Philip B. Perlman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAACP Strategy in the Covenant Cases Clement E

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 6 | Issue 2 1955 NAACP Strategy in the Covenant Cases Clement E. Vose Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clement E. Vose, NAACP Strategy in the Covenant Cases, 6 W. Res. L. Rev. 101 (1955) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol6/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 1955) NAACP Strategy in the Covenant Cases Clement E. Vose ON MAY 3, 1948, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that neither federal nor state courts may issue injunctions to enforce racial re- strictive covenants.1 This decision reversed thirty years of history during which privately-drawn housing restrictions against Negroes had been en- forced by the courts of nineteen states and the District of Columbia. Be- cause precedent and the Restatement of Property,2 issued by the American Law Institute in 1944, favored judicial sanction of racial covenants, the Supreme Coures decision gave a surprising turn to legal development. On the other hand, when the Negroes' political power THE AuTHOR (AD., 1947, University of and legal skill is taken into Maine; M.A., 1949, PhD., 1952, University of account their victory in the Wisconsin) is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Western Reserve University. -

Alan S. Rosenthal, Esquire

ALAN S. ROSENTHAL, ESQUIRE Oral History Project The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit Oral History Project United States Courts The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit District of Columbia Circuit ALAN S. ROSENTHAL, ESQUIRE Interviews conducted by: Judith S. Feigin, Esquire In 2011: March 3, March 21, April 20, May 9, May 23, June 6, June 20 July 18 and July 25 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .. i Oral History Agreements Alan S. Rosenthal, Esquire. iii Judith S. Feigin, Esquire. v Oral History Transcript of Interviews: Interview No. 1, March 3, 2011. 1 Interview No. 2, March 21, 2011. 29 Interview No. 3, April 20, 2011.. 63 Interview No. 4, May 9, 2011. 93 Interview No. 5, May 23, 2011. 122 Interview No. 6, June 6, 2011. 151 Interview No. 7, June 20, 2011. 177 Interview No. 8, July 18, 2011.. 206 Interview No. 9, July 25, 2011.. 236 Epitaph by Mr. Rosenthal, May 2012. A-1 Index. B-1 Table of Cases. C-1 Biographical Sketches Alan S. Rosenthal, Esquire. D-1 Judith S. Feigin, Esquire. D-3 NOTE The following pages record interviews conducted on the dates indicated. The interviews were recorded digitally or on cassette tape, and the interviewee and the interviewer have been afforded an opportunity to review and edit the transcript. The contents hereof and all literary rights pertaining hereto are governed by, and are subject to, the Oral History Agreements included herewith. © 2012 Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit. All rights reserved. PREFACE The goal of the Oral History Project of the Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit is to preserve the recollections of the judges of the Courts of the District of Columbia Circuit and lawyers, court staff, and others who played important roles in the history of the Circuit. -

Green V. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore's

Green v. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium 1953 Renovation and upper deck construction of Memorial Stadium1 Jordan Vardon J.D. Candidate, May 2011 University of Maryland School of Law Legal History Seminar: Building Baltimore 1 Kneische. Stadium Baltimore. 1953. Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore. Courtesy of Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Library Resource Center, Baltimore, Maryland. Table of Contents I. Introduction........................................................................................................3 II. Historical Background: A Brief History of the Location of Memorial Stadium..............................................................................................................6 A. Ednor Gardens.............................................................................................8 B. Venable Park..............................................................................................10 C. Mount Royal Reservoir..............................................................................12 III. Venable Stadium..............................................................................................16 A. Financial History of Venable Stadium.......................................................19 IV. Baseball in Baltimore.......................................................................................24 V. The Case – Not a Temporary Arrangement.....................................................26 -

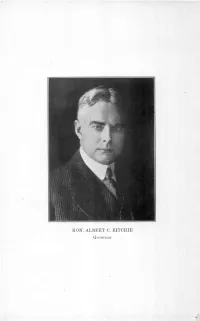

HON. ALBERT C. RITCHIE Governor -3-^3-/6" '' C ^ O 1 N J U

HON. ALBERT C. RITCHIE Governor -3-^3-/6" '' c ^ o 1 n J U MARYLAND MANUAL l 925 A Compendium of Legal, Historical and Statistical Information Relating to the STATE OF MARYLAND Compiled by E. BROOKE LEE, Secretary of State. 20TH CENTURY PRINTING CO. BALTIMORE. MD. State Government, 1925 EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT State House, Annapolis. Baltimore Office 603 Union Trust Building. (iovernor: Albert C. Ritchie Baltimore City Secretary of State: E. Brooke Lee Silver Spring Executive Secretary: Kenneth M. Burns. .Baltimore Stenographers: Miss Virginia Dinwiddie Ellinger ; Baltimore Mrs. Bettie Smith ...Baltimore Clerks: Murray G. Hooper Annapolis Raymond M. Lauer. — Annapolis Chas. Burton Woolley .Annapolis The Governor is elected by the people for a term of four years from the second Wednesday in January ensuing his election (Constitu- tion, Art. 2, Sec. 2) ;* The Secretary of State is appointed by the Gov- ernor, with the consent of the Senate, to hold office during the term of the Governor; all other officers are appointed by the Governor to hold office during his pleasure Under the State Reorganization Law, which became operative Janu- ary 1, 1923, the Executive Department was reorganized and enlarged to include, besides the Secretary of State, the following: Parole Commis- sioner, The Commissioner of the Land Office, The Superintendent of Pub- lic Buildings, The Department of Legislative Reference, The Commis- sioners for Uniform State Laws, The State Librarian. The Secretary of State, in addition to his statutory duties, is the General Secretary -

The Viability of Multi-Party Litigation As a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades After the Restrictive Covenant Cases

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2011 The iV ability of Multi-Party Litigation as a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades after the Restrictive Covenant Cases José F. Anderson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation The iV ability of Multi-Party Litigation as a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades after the Restrictive Covenant Cases, 42 McGeorge L. Rev. 765 (2011) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Viability of Multi-Party Litigation as a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades After the Restrictive Covenant Cases Jose Felipe Anderson ISSUE 4 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1945914 The Viability of Multi-Party Litigation as a Tool for Social Engineering Six Decades After the Restrictive Covenant Cases Jos6 Felip6 Anderson* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................... ..... 766 H. THE McGHEE V. SIPES BRIEF ................................... 774 A. McGhee Argument Against Judicial Enforcement of Restrictive Covenants .............................................. 776 B. History of Restrictive Covenants ............................. 777 C. Policy Arguments ......................................... 782 D. Deference to the UN Charter .......................................786 III. THE SHELLEY V. KRAEMER DECISION .............................. 787 IV. ANALYSIS .................................................. 789 V. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

1970 Annual Report of the FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION

HD2775 1970 C.2 Annual Report of the FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION 1970 Annual Report of the FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1970 --------------------------------------------------------- For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 40 cents (paper cover) Federal Trade Commission CASPAR W. WEINBERGER, Chairman PAUL RAND DIXON, Commissioner PHILIP ELMAN, Commissioner EVERETTE, MACINTYRE, Commissioner MARY GARDINER JONES, Commissioner BASIL J. MEZINES, Executive Assistant to Chairman JOSEPH W. SHEA, Secretary JOHN A. DELANEY, Acting Executive Director JOHN V. BUFFINGTON, General Counsel EDWARD CREEL, Director of Hearing Examiners FRANK C. HALE, Director, Bureau of Deceptive Practices ROY A. PREWITT, Acting Director, Bureau of Economics CHARLES R. MOORE, Acting Director, Bureau of Field Operations CECIL G. MILES, Director, Bureau of Restraint of Trade HUGH B. HELM, Acting Director, Bureau of Industry Guidance HENRY D. STRINGER, Director, Bureau of Textiles and Furs WILLIAM D. YANCEY, Acting Comptroller JOHN A. DELANEY, Director, Office of Administration DAVID H. BUSWELL, Director, Office of Public Information ii EXECUTIVE OFFICES OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION Pennsylvania Avenue at Sixth St., NW. Washington, D.C. 20580 Field Offices Atlanta, Ga. Los Angeles, Calif. Room 720 Room 13209 730 Peachtree St. N.W. 11000 Wilshire Blvd. Zip code: 30308 Zip code: 90024 Boston, Mass. New Orleans, La. JFK Federal Building 1000 Masonic Temple Bldg. Government Center 333 St. Charles St. Zip code: 02203 Zip code: 70130 Chicago, Ill. New York, N.Y. Room 486 22nd Floor U.S. Courthouse and Federal Building Federal Office Building 26 Federal Plaza 219 S. -

Statutory Interpretation--In the Classroom and in the Courtroom

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1983 Statutory Interpretation--in the Classroom and in the Courtroom Richard A. Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Posner, "Statutory Interpretation--in the Classroom and in the Courtroom," 50 University of Chicago Law Review 800 (1983). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Statutory Interpretation-in the Classroom and in the Courtroom Richard A. Posnerf This paper continues a discussion begun in an earlier paper in this journal.1 That paper dealt primarily with the implications for statutory interpretation of the interest-group theory of legislation, recently revivified by economists; it also dealt with constitutional interpretation. This paper focuses on two topics omitted in the earlier one: the need for better instruction in legislation in the law schools and the vacuity of the standard guideposts to reading stat- utes-the "canons of construction." The topics turn out to be re- lated. The last part of the paper contains a positive proposal on how to interpret statutes. I. THE ACADEMIC STUDY OF LEGISLATION It has been almost fifty years since James Landis complained that academic lawyers did not study legislation in a scientific (i.e., rigorous, systematic) spirit,' and the situation is unchanged. There are countless studies, many of high distinction, of particular stat- utes, but they are not guided by any overall theory of legislation, and most academic lawyers, like most judges and practicing law- yers, would consider it otiose, impractical, and pretentious to try to develop one. -

Judge Posner Through Dissenting Eyes

Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 6 2000 Judge Posner through Dissenting Eyes Richard D. Cudahy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp Recommended Citation Richard D. Cudahy, Judge Posner through Dissenting Eyes, 17 J. Contemp. Health L. & Pol'y xxxi (2001). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp/vol17/iss1/6 This Dedication is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUDGE POSNER THROUGH DISSENTING EYES The Honorable Richard D. Cudahy* What follows may be an unusual attempt at a dedicatory essay. But these are memories that come quickly to mind in connection with a colleague whom I esteem and respect in every way and to whom this issue of THE JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY HEALTH LAW AND POLICY is dedicated. On December 4, 1981, Richard Posner was named to the Seventh Circuit - one of the first of seven appointments by President Ronald Reagan to our court. As the first, last, and only appointee of President Carter to the same court, I awaited this event with bated breath - and some trepidation. At that point in history, there had been enough oratory about out-of-control federal judges taking the affairs of the country into their own hands to make one wonder what was in store with the new administration. And the arrival of Dick Posner did not disappoint. -

The Maryland Board of Public Works

The Maryland Board of Public Works The Maryland Board of Public Works A History Alan M. Wilner Hall of Records Commission, Department of General Services, Annapolis, MD 21404 Contents FOREWORD Vll PREFACE ix CHAPTER 1. An Overview of Early Policies: To 1825 CHAPTER 2. The First Board of Public Works and the Mania 1 for Internal Improvements, 1825-1850 CHAPTER 3. The Constitutional Convention of 1850-1851 11 CHAPTER 4. The Reign of the Commissioners: 1851-1864 25 CHAPTER 5. The Constitutional Convention of 1864 35 CHAPTER 6. The New Board: 1864-1920 51 CHAPTER 7. The Modern Board: 1920-1960 59 CHAPTER 8. The Overburdened Board: 1960-1983 79 CHAPTER 9. Epilogue 99 APPENDIX A. Commissioners of Public Works and Members of 123 the Board of Public Works, 1851-1983 125 APPENDIX B. Guide to the Records of the Board of Public Works, 1851-1983 127 BIBLIOGRAPHY 185 INDEX 189 The Maryland Board of Public Works, A History, is available from the Maryland Hall of Records, P.O. Box 828, Annapolis, MD 21404. Copyright © 1984 by Alan M. Wilner. Foreword Alan M. Wilner's authorship of the history of the Board of Public Works continues a fine Maryland tradition of jurist-historians that includes Judge Carroll Bond's His- tory of the Court of Appeals and Judge Edward Delaplaine's biography of Governor Thomas Johnson. When I first read Judge Wilner's manuscript in the summer of 1981, it was im- mediately clear that it would provide an excellent introduction to the significant col- lection of archival materials at the Hall of Records relating to the history and work of the Board. -

Conflict Among the Brethren: Felix Frankfurter, William O. Douglas And

CONFLICT AMONG THE BRETHREN: FELIX FRANKFURTER, WILLIAM 0. DOUGLAS AND THE CLASH OF PERSONALITIES AND PHILOSOPHIES ON THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT MELVIN I. UROFSKY* Following the constitutional crisis of 1937, the personnel of the United States Supreme Court changed rapidly as Franklin Roosevelt named new Justices whom he believed committed to the modem views of the New Deal. Roosevelt appointees constituted a majority of the Court by 1942, but instead of harmony, the Court entered one of the most divi- sive periods in its history. The economic issues which had dominated the Court's calendar for nearly a half-century gave way to new questions of civil liberties and the reach of the Bill of Rights, and these cast the juris- prudential debate between judicial restraint and judicial activism in a new light. The struggle within the Court in the early 1940s can be ex- amined not only in terms of competing judicial philosophies, but by look- ing at personalities as well. Felix Frankfurter and William 0. Douglas, both former academics, both intimates of Franklin Roosevelt and par- tisans of the New Deal, both strong-willed egotists, and both once friends, personified in their deteriorating relationship the philosophical debate on the Court and how personality conflicts poisoned the once placid waters of the temple pool. I. THE PRE-COURT YEARS On January 4, 1939, shortly after Franklin D. Roosevelt had sent to the Senate the nomination of Felix Frankfurter as Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, a group of top New Dealers gathered to celebrate in the office of Secretary of the Interior Harold L. -

Civil Rights and the Role of the Solicitor General

Twins at Birth: Civil Rights and the Role of the Solicitor General SETH P. WAXMAN* It is painful even today to contemplate the awful devastation wreaked upon this nation by the War Between the States. But like most cataclysms, the Civil War also gave birth to some important positive developments. I would like to talk with you today abouttwo such offspring ofthat war, and the extentto which, like many sibling pairs, they have influenced each other's development. The first child-the most well-known progeny of the Civil War-was this country's commitment to civil rights. The war, of course, ended slavery. But it did not-and could not--change the way Americans thought about and treated each other. Civil rights and their polestar, the principle of equal protection of the laws, encompass far more than the absence of state-sanctioned servitude. The Congresses and Presidents that served in the wake of the Civil War aimed at this more fundamental and difficult goal. They brought about ratification of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. And they enacted a variety of laws designed to enforce the guarantees of those Amendments. But as history shows so agonizingly, it takes much more than well-meaning laws--or even constitutional amendments-to reweave the social fabric of a nation. In the first place, a law that is merely on the books is quite different from one that is actually enforced. And what is more, a law that is enacted will not necessarily even remain on the books. Under the principle ofjudicial review established in Marbury v.