Cattails, Spring 2021 (March, April, May)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Places of Psychology: Consciousness in Virginia Woolf's Major Novels

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects English Spring 2010 The Dark Places of Psychology: Consciousness in Virginia Woolf's Major Novels Linda Martin Illinois Wesleyan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/eng_honproj Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Linda, "The Dark Places of Psychology: Consciousness in Virginia Woolf's Major Novels" (2010). Honors Projects. 25. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/eng_honproj/25 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Martin 1 Linda Martin Dr. Wes Chapman English 485 5 April 2010 The Dark Places of Psychology: Consciousness in Virginia Woolf’s Major Novels When Virginia Woolf published her 1919 essay “Modern Fiction,” she threw down a gauntlet. Defining herself and her peers against the previous generation of established authors (particularly the “Edwardian” writers H.G. Wells, Arnold Bennett, and John Galsworthy), in “Modern Fiction” Woolf challenges her contemporaries to disregard Edwardian tradition and forge a new era of English literature. -

Acquisition Reform and the New V-22 OSPREY Program

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1998-03 A case study: acquisition reform and the new V-22 OSPREY program Riegert, Paul M. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/8053 OUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE- S M0NTI5BEY CA 9 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS A CASE STUDY: ACQUISITION REFORM AND THE NEW V-22 OSPREY PROGRAM by Paul M. Riegert March 1998 Thesis Advisor: Michael M. Boudreau Second Reader: Dr. Sandra W. Desbrow Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED March 1998 Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS A CASE STUDY: ACQUISTION REFORM AND THE NEW V-22 OSPREY PROGRAM 6. AUTHOR(S) Paul M. Riegert 8. PERFORMING 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) ORGANIZATION REPORT Naval Postgraduate School NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. -

Effects of Red Diamondback Rattlesnake Venom on Keloid Dermal Fibroblasts in Vitro a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Effects of Red Diamondback Rattlesnake Venom on Keloid Dermal Fibroblasts In Vitro A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science By: Mackenzie Shelby Newman B.S., Miami University 2011 WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL 10 January 2014 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Mackenzie Newman ENTITLED Effects of Red Diamondback Rattlesnake Venom on Keloid Dermal Fibroblasts In Vitro BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science. _____________________________ Richard Simman, M.D., Thesis Director _____________________________ Norma C. Adragna, Ph.D. Interim Chair, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Richard Simman, M.D. _____________________________ David Cool, Ph.D. _____________________________ Sharath Krishna, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. Interim Chair, Graduate School ABSTRACT Newman, Mackenzie. M.S., Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology, Wright State University, 2013. Effects of Red Diamondback Rattlesnake Venom on Keloid Dermal Fibroblasts In Vitro Keloid scarring is an inflammatory healing response to physical injury such as incision or piercing in the dermis. It is characterized by aberrant extracellular matrix production, the overaccumulation of mature collagen, and excessive fibroblast proliferation and migration beyond the borders of the original wound site. This results in swelling, depigmentation, itchiness, and pain akin to a benign tumor. Although there are myriad treatments for the condition, most are invasive and exhibit a high recurrence rate. Previous studies have shown that rattlesnake venom stimulates apoptosis in the skin via multiple specific mechanisms, largely composed of extracellular matrix and its receptors’ interactions. -

Fiction Catàleg

Spring 2021 Fiction Rights Guide Creative Management 19 West 21st St. Suite 501, New York, NY 10010 / Telephone: (212) 765-6900 / E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS THE REDSHIRT THE ALMOST QUEEN RAFT OF STARS WHITE ON WHITE THE ROCK EATERS BEND YOU TO REMAIN IMPOSTER SYNDROME NEXT SHIP HOME SURVIVE THE NIGHT WALK THE VANISHED EARTH THREE WORDS FOR GOODBYE THE MAN WHO SOLD AIR IN THE HOLY LAND NOBODY, SOMEBODY, ANYBODY WILD CAT THE BACHELOR CHEVY IN THE HOLE THE LAST MONA LISA THE COMMUNITY BOARD IMMEDIATE FAMILY FOR THE LOVE OF THE BARD THE BODY SCOUT THE WILD ONE O, BEAUTIFUL NONE OF THIS WOULD HAVE HAPPENED... THE UNKNOWN WOMAN OF THE SEINE MORE OF EVERYTHING ALL HER LITTLE SECRETS FLIGHT THE LIGHT PIRATE ISLANDERS GO HOME, RICKY! EXOSKELETONS CAIRO CIRCLES THE MYTHMAKERS THE REDSHIRT A Novel By Corey Sobel NA October 2020 / University Press of Kentucky Final PDF Available Shortlisted for 2020 Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize Corey Sobel challenges tenacious stereotypes in this compelling debut novel, shedding new light on the hypermasculine world of American football. The Redshirtintroduces Miles Furling, a young man who is convinced he was placed on earth to play football. Deep in the closet, he sees the sport as a means of gaining a permanent foothold in a culture that would otherwise reject him. Still, Miles’s body lags behind his ambitions, and recruiters tell him he is not big enough to com- pete at the top level. His dreams come true when a letter arrives from King College. -

The Art of Writing Proposals by Adam Przeworski and Frank Salomon

1988, 1995 The Art of Writing Proposals By Adam Przeworski and Frank Salomon Writing proposals for research funding is a peculiar facet of North American academic culture, and as with all things cultural, its attributes rise only partly into public consciousness. A proposal's overt function is to persuade a committee of scholars that the project shines with the three kinds of merit all disciplines value, namely, conceptual innovation, methodological rigor, and rich, substantive content. But to make these points stick, a proposal writer needs a feel for the unspoken customs, norms, and needs that govern the selection process itself. These are not really as arcane or ritualistic as one might suspect. For the most part, these customs arise from the committee's efforts to deal in good faith with its own problems: incomprehension among disciplines, work overload, and the problem of equitably judging proposals that reflect unlike social and academic circumstances. Writing for committee competition is an art quite different from research work itself. After long deliberation, a committee usually has to choose among proposals that all possess the three virtues mentioned above. Other things being equal, the proposal that is awarded funding is the one that gets its merits across more forcefully because it addresses these unspoken needs and norms as well as the overt rules. The purpose of these pages is to give competitors for Council fellowships and funding a more even start by making explicit some of those normally unspoken customs and needs. Capture -

To Live from a New Root': the Uneasy Consolation of <I>All

Volume 16 Number 1 Article 4 Fall 10-15-1989 To Live From a New Root’: The Uneasy Consolation of All Hallows’ Eve Marlene Marie McKinley Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation McKinley, Marlene Marie (1989) "To Live From a New Root’: The Uneasy Consolation of All Hallows’ Eve," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 16 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol16/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Analyzes Williams’s view of love in All Hallows’ Eve, noting the challenging and disquieting notion of giving up earthly attachments and definitions of the phrase to “live from a new root.” Additional Keywords Death in All Hallows’ Eve; Life after death in All Hallows’ Eve; Love and death in All Hallows’ Eve; Williams, Charles. -

Utah Wolf Management Plan

UTAH WOLF MANAGEMENT PLAN Utah Division of Wildlife Resources Publication #: 05-17 Prepared by: The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources & The Utah Wolf Working Group UTAH WOLF MANAGEMENT PLAN Table of Contents List of Tables ........................................................................................... i List of Figures ......................................................................................... ii Executive Summary ................................................................................ iii Dedication ............................................................................................... iv Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 Part I. Gray Wolf Ecology and Natural History .................................... 4 Description ............................................................................................... 4 Distribution ............................................................................................... 4 Sign .......................................................................................................... 5 Taxonomy ................................................................................................ 5 Reproduction ............................................................................................ 6 Mortality .................................................................................................... 6 Social Ecology ......................................................................................... -

Identification, Properties, and Synthesis of an Unknown Ionic Compound

Identification, Properties, and Synthesis of an Unknown Ionic Compound Chemistry 101 Laboratory, Section 004 Instructor: Linna Yinling February 17, 2015 Our signatures indicate that this document represents the work completed by our group this semester. Goals The goals of this experiment are to identify our given unknown compound and to identify as many chemical and physical properties of the compound as possible. Our final goal will be to devise two syntheses of our compound, which we will evaluate for cost effectiveness and the yield of compound they could potentially give us. Experimental Design We first performed the positive test with the unknown compound to determine what the unknown contains. Once the unknown was discovered, we did the five chemical reactions with the known compound (NaCl) to make sure it matched the unknown compound NaCl. The first chemical reaction was done with AgNO3 to test for the presence of Chloride. We added a small amount of sodium chloride and small amount of water to the test tube. We then added the compound AgNO3. If the reaction was positive then there would be precipitation and the mixture would turn a cloudy white and solid would form on the bottom. If the reaction was negative there would be no reaction and the mixture would stay clear. The second reaction was done with BaCl2 to test for the presence of sulfate. We added a small amount of sodium chloride and a small amount of water to the test tube. We then added the compound BaCl2. If the reaction was positive then there would be precipitation and we would know our compound contained sulfate. -

Primates' Food Preferences Predict Their Food Choices Even Under Uncertain Conditions

ABC 2021, 8(1):69-96 Animal Behavior and Cognition DOI: https://doi.org/10.26451/abc.08.01.06.2021 ©Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) Primates’ Food Preferences Predict Their Food Choices Even Under Uncertain Conditions Sarah M. Huskisson1, Crystal L. Egelkamp1, Sarah L. Jacobson1,2, Stephen R. Ross1, & Lydia M. Hopper1* 1 Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes, Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, IL, USA 2 The Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA *Corresponding author (Email: [email protected]) Citation – Huskisson, S. M., Egelkamp, C. L., Jacobson, S. L., Ross, S. R., & Hopper, L. M. (2021). Primates’ food preferences predict their food choices even under uncertain conditions. Animal Behavior and Cognition, 8(1), 69-96. https://doi.org/10.26451/abc.08.01.06.2021 Abstract – Primates’ food preferences are typically assessed under conditions of certainty. To increase ecological validity, and to explore primates’ decision making from a comparative perspective, we tested three primate species (Pan troglodytes, Gorilla gorilla gorilla, Macaca fuscata) (N = 18) in two food-preference tests that created different conditions of uncertainty. In the first, we showed subjects pairs of photographs of six foods in a randomized manner within each session, so subjects could not predict the next pairing and had to respond in accordance with their preferences. We found individual differences in subjects’ preference and differences in six subjects’ preferences when comparing their selections in this test to selections made when trials were blocked by food pairing (tested previously: Huskisson et al., 2020). -

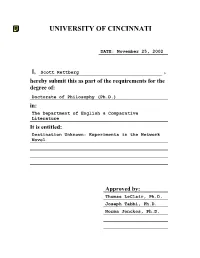

Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: November 25, 2002 I, Scott Rettberg , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in: The Department of English & Comparative Literature It is entitled: Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel Approved by: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. Joseph Tabbi, Ph.D. Norma Jenckes, Ph.D. Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2003 by Scott Rettberg B.A. Coe College, 1992 M.A. Illinois State University, 1995 Committee Chair: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. Abstract The dissertation contains two components: a critical component that examines recent experiments in writing literature specifically for the electronic media, and a creative component that includes selections from The Unknown, the hypertext novel I coauthored with William Gillespie and Dirk Stratton. In the critical component of the dissertation, I argue that the network must be understood as a writing and reading environment distinct from both print and from discrete computer applications. In the introduction, I situate recent network literature within the context of electronic literature produced prior to the launch of the World Wide Web, establish the current range of experiments in electronic literature, and explore some of the advantages and disadvantages of writing and publishing literature for the network. In the second chapter, I examine the development of the book as a technology, analyze “electronic book” distribution models, and establish the difference between the “electronic book” and “electronic literature.” In the third chapter, I interrogate the ideas of linking, nonlinearity, and referentiality. -

Graphic Novels and Critical Literacy Theory: Understanding the Immigrant Experience in American Public Schools

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Education Doctoral Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. School of Education 5-2016 Graphic Novels and Critical Literacy Theory: Understanding the Immigrant Experience in American Public Schools Michael Maloy St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd Part of the Education Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Maloy, Michael, "Graphic Novels and Critical Literacy Theory: Understanding the Immigrant Experience in American Public Schools" (2016). Education Doctoral. Paper 250. Please note that the Recommended Citation provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd/250 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Graphic Novels and Critical Literacy Theory: Understanding the Immigrant Experience in American Public Schools Abstract The purpose of the study was to bring light to a persistent and growing problem in American public schools. There is a fundamental lack of understanding on the part of school personnel and native-born American students about the unique needs and challenges faced by English language learners (ELLs) and immigrant students in American schools. The study investigated if having students read graphic novels, while using critical literacy theory as an analytical lens, helped non-ELL students foster deeper understanding about the unique challenges facing ELL and immigrant children. -

Inverse Design of Two-Dimensional Centrifugal Pump Impeller Blades

Inverse Design of Two-Dimensional Centrifugal Pump Impeller Blades using Inviscid Analysis and OpenFOAM A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Dynamic Systems of the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences by Omkar Champhekar Bachelor of Technology, Mechanical Engineering University of Pune, India, August 2007 July 2012 Advisor: Dr. Urmila Ghia/Dr. Kirti Ghia Abstract Inverse design of centrifugal pump impeller blades is a widely used technique for designing pump blades. In a typical Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) analysis, the geometry (flow domain) is prescribed, and the governing equations are solved over the flow domain, subject to appropriate boundary conditions. In the inverse design technique, the geometry is unknown, while the desired flow field characteristics on the geometry (blades of pump impeller) are prescribed. Starting with an initial guess for the blade shape, the final shape of the blades is obtained iteratively. The present work uses OpenFOAM, an open source CFD software, which solves the governing equations using a finite-volume method (FVM) for the inverse design of two-dimensional centrifugal pump impeller blades. A CFD analysis using FVM requires mesh to be of good quality. Since the pump blade has high curvature, careful consideration has to be given while generating the mesh. The present work explains the geometry generation and meshing of the geometry, to obtain a good quality mesh in the Gambit software. The inverse design technique in the present study is based on assumption of a potential flow field.