Judicial Review of Icc Security Authorizations: the Relevance of Unapproved Control*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Vegan Climate

US Vegan Climate ETF Schedule of Investments April 30, 2021 (Unaudited) Shares Security Description Value COMMON STOCKS - 99.4% Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services - 13.4% 1,675 Accenture plc - Class A $ 485,700 233 Allegion plc 31,311 107 Booking Holdings, Inc. (a) 263,870 293 Broadridge Financial Solutions, Inc. 46,479 317 Equifax, Inc. 72,666 352 Expedia Group, Inc. 62,033 70 Fair Isaac Corporation (a) 36,499 729 Fidelity National Financial, Inc. 33,257 214 FleetCor Technologies, Inc. (a) 61,572 782 Global Payments, Inc. 167,841 961 IHS Markit, Ltd. 103,384 5,607 Mastercard, Inc. - Class A 2,142,210 425 Moody's Corporation 138,852 212 MSCI, Inc. 102,983 3,091 PayPal Holdings, Inc. (a) 810,738 491 TransUnion 51,354 8,745 Visa, Inc. - Class A 2,042,482 6,653,231 Construction - 0.9% 890 DR Horton, Inc. 87,478 1,956 Johnson Controls International plc 121,937 705 Lennar Corporation - Class A 73,038 19 NVR, Inc. (a) 95,344 682 PulteGroup, Inc. 40,320 396 Sunrun, Inc. (a) 19,404 437,521 Finance and Insurance - 14.1% 1,735 Aflac, Inc. 93,222 40 Alleghany Corporation (a) 27,159 797 Allstate Corporation 101,060 969 Ally Financial, Inc. 49,855 1,588 American Express Company 243,520 2,276 American International Group, Inc. 110,272 314 Ameriprise Financial, Inc. 81,138 657 Anthem, Inc. 249,259 596 Aon plc - Class A 149,858 1,025 Arch Capital Group, Ltd. (a) 40,703 496 Arthur J. -

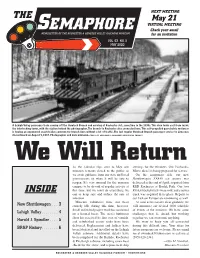

Inside the Interlocking Tower, with the Station Behind the Photographer

NEXT MEETING: May 21 VIRTUAL MEETING Check your email for an invitation VOL. 63 NO. 5 MAY 2020 A Lehigh Valley passenger train coming off the Hemlock Branch and arriving at Rochester Jct., sometime in the 1930s. This view looks east from inside the interlocking tower, with the station behind the photographer. The branch to Rochester also connected here. This self-propelled gas-electric motorcar is towing an unpowered coach trailer, common for branch lines without a lot of traffic. The last regular Hemlock Branch passenger service to Lima was discontinued on August 9, 1937. Photographer and date unknown. COURTESY ANTHRACITE RAILROADS HISTORICAL SOCIETY We Will Return As the calendar flips over to May, our awnings for the windows. Our Fairbanks- museum remains closed to the public as Morse diesel is being prepared for service. we await guidance from our state and local On the equipment side, our new governments on when it will be safe to Shuttlewagon SX430 car mover was reopen. It’s very unusual for the museum delivered at the end of April, acquired from campus to be devoid of regular activity at RED Rochester at Kodak Park. Our two INSIDE this time, but we must do everything we RG&E bucket trucks were sold, and a newer can to keep safe and reduce the rate of truck was acquired in its place. Repairs to infection. our Jackson Tamper are continuing as well. New Shuttlewagon ...3 Museum volunteers have not been As soon as we receive clear guidance, we entirely idle during this time, however. will announce our revised 2020 schedule Lehigh Valley ........4 Small individual project work has continued of events at the museum. -

Loss of Rail Competition As an Issue in the Proposed Sale of Conrail to Norfolk Southern: Valid Concern Or Political Bogeyman

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Article 6 1986 Loss of Rail Competition as an Issue in the Proposed Sale of Conrail to Norfolk Southern: Valid Concern or Political Bogeyman Mark D. Perreault Nancy S. Fleischman Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, and the Transportation Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Mark D. Perreault & Nancy S. Fleischman, Loss of Rail Competition as an Issue in the Proposed Sale of Conrail to Norfolk Southern: Valid Concern or Political Bogeyman, 34 Clev. St. L. Rev. 413 (1985-1986) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOSS OF RAIL COMPETITION AS AN ISSUE IN THE PROPOSED SALE OF CONRAIL TO NORFOLK SOUTHERN: VALID CONCERN OR POLITICAL BOGEYMAN? MARK D. PERREAULT* NANCY S. FLEISCHMAN** 1. INTRODUCTION ......... ..................................... 414 II. PRESERVATION OF RAIL-RAIL COMPETITION AS A CONSIDERATION IN RAIL CONSOLIDATIONS ............................... 414 A . Prior to 1920 ................................. 414 B . 1920 - 1940 .................................. 418 C. 1940 - 1980 .................................. 421 D . 1980 - Present ................................ 425 Ill. PRESERVATION OF RAIL-RAIL COMPETITION AS A CONSIDERATION IN THE FORMATION OF CONRAIL AND SUBSEQUENT DETERMINATION TO SELL CONRAIL ........ ........................................ 428 A. 1970's Congressional Response to the Penn Central and Other Railroad Bankruptcies ..................... 428 B. Foundation of Initial CongressionalPolicy ........... 429 C. Implementing the Policy ......................... 432 D. -

Washington, Saturday, August 14, 1937

FEDERAL REGISTER \ VOLUME 2 1934 NUMBER 157 C ^A/ITEO ^ Washington, Saturday, August 14, 1937 TREASURY DEPARTMENT. plemental oral presentation of views shall be submitted to the Committee for Reciprocity Information not later than twelve Bureau of Customs. o ’clock noon, May 3, 1937. They should be addressed to “Acting rrhairma.n, Committee for Reciprocity Information, Old Land Office [T. D. 49109] Building, 8th and E Streets, Northwest, Washington, D. C.” Sup F oreign-T rade Agreements plemental oral statements will be heard at a public hearing be ginning at ten o’clock a. m., on May 17, 1937, before the Commit PUBLIC NOTICE OP INTENTION TO NEGOTIATE A FOREIGN-TRADE tee for Reciprocity Information, in the hearing room of the Tariff AGREEMENT WITH THE GOVERNMENT OP ECUADOR Commission in the Old Land Office Building. August 2, 1937. Form and Manner of Presentation To Whom It May Concern: The Committee for Reciprocity Information has prescribed the Pursuant to section 4 of the act of Congress approved June following regulations governing the submission of written and 12, 1934, and extended on March 1, 1937, entitled “An Act oral statements: Written statements must be either typewritten or printed. to Amend the Tariff Act of 1930” and Executive Order No. They must be submitted in sextuplícate and at least one copy 6750 of June 27, 1934, the Secretary of State on April 5, must be sworn to. Such statements will be treated as confiden 1937, gave formal notice of intention to negotiate a foreign- tial, for the use only of the Interdepartmental trade agreements trade agreement with the Government of Ecuador. -

SEC News Digest, 07-16-1970

ECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION J!~~ IDU@rn~1r • • brief summary of financial proposals filed with and actions by the S.E.C. COJ\1Miss(t Washington, D.C. 20549 ( In ord.ring full ,.,,' of Releaaes from SEC Publications Unit cite number) (Ias. Ro. 70-137) FOR RELEASE _---:;;J.;:;u""'ly<......:l.=..6.....-=l:..:;.9.:..;70~_ COMMISSION ANNOlJNCEKENT NYSE REPORT ON !fEW RAT! SCHEDULE. The SEC announced today that it will make available for public ex.. lnation the report submitted to it by the New York Stock Exchange containing a commisaion rate proposal and analysis for the determination of proposed rate levels. The submiasion consista of a "Report on the New ec..i.aion bte Schedule" prepared by the Committee on Member Firm Costs and Revenues of the New York ~tock Exchange and a two volume report prepared by National Economic Research Aaaociation, Inc. entitled Stock"Brokerage C~i .. ions: The Development and Application of Standards of Reaaonableneas for Public aet.s. Copies of the reports will be made available for examination at the Commission'a officea. Requests for obtaining copies of the reports should be directed to the Secretary of the New York Stock Exchange et 11 Wall Street, New York, N. Y. 10005. As indicated in Exchange Act Releaae No. 8924, the Commis.ion invites interested persons, including the other exchsnges, to submit their views on the proposed new minbDum commission rates of the New York Stock Exchange and requests any persons who may wiah to preseut teatimony to file appropriate summaries of their presentations with the Secretary of the Commisaion 500 North Capitol Street, Washington, D. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 4847 the Chief Clerk Read the Nomination of John Bright Hill Mr

1933 .CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 4847 The Chief Clerk read the nomination of John Bright Hill Mr. GREEN, Mr. Speaker, it is my purpose at a later to be collector, customs collection district no. 15, Wilming .. date to speak on the subject of the canal across Florida, but ton, N.C. this morning I ask unanimous consent to extend my re The VICE PRESIDENT. Without objection, the nomina .. marks and present therein a memorial from my legislature tion is confirmed. to the Congress. The Chief Clerk read the nomination of James J. Connors The SPEAKER. Is there objection to the request of the to be collector, customs collection district no. 31, Juneau, gentleman from Florida? Alaska. There was no objection. The VICE PRESIDENT. Without objection, the nomina.. Mr. GREEN. Mr. Speaker and my colleagues, the canal tion 1s confirmed. aero~ north Florida is the most important waterway which DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR has been suggested since the construction of the Panama The Chief Clerk read the nomination of William Zimmer Canal. It, we believe, will handle as much or probably more tonnage than is handled by the Panama Canal and will re .. man, Jr., of Illinois, to be Assistant Commissioner of Indian dound greater benefits to the American people. Affairs. The VICE PRESIDENT. Without objection, the nomina The proposed canal acl'oss north Florida is by no means a local project, but is decidedly a national project and will tion is confirmed. benefit every one of the States of the Union and all citizens That completes the calendar. therein. RECESS This project has been a dream of several generations, but Mr. -

ALLEGHANY CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 51-0283071 (State Or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K ¥ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2007 OR n TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 1-9371 ALLEGHANY CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 51-0283071 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 7 Times Square Tower, 10036 New York, New York (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 212/752-1356 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, $1.00 par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Not applicable Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¥ No n Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes n No ¥ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Loss of Rail Competition As an Issue in the Proposed Sale of Conrail to Norfolk Southern: Valid Concern Or Political Bogeyman Mark D

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Cleveland State Law Review Law Journals 1986 Loss of Rail Competition as an Issue in the Proposed Sale of Conrail to Norfolk Southern: Valid Concern or Political Bogeyman Mark D. Perreault Nancy S. Fleischman Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, and the Transportation Law Commons How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Recommended Citation Mark D. Perreault & Nancy S. Fleischman, Loss of Rail Competition as an Issue in the Proposed Sale of Conrail to Norfolk Southern: Valid Concern or Political Bogeyman, 34 Clev. St. L. Rev. 413 (1985-1986) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOSS OF RAIL COMPETITION AS AN ISSUE IN THE PROPOSED SALE OF CONRAIL TO NORFOLK SOUTHERN: VALID CONCERN OR POLITICAL BOGEYMAN? MARK D. PERREAULT* NANCY S. FLEISCHMAN** 1. INTRODUCTION ......... ..................................... 414 II. PRESERVATION OF RAIL-RAIL COMPETITION AS A CONSIDERATION IN RAIL CONSOLIDATIONS ............................... 414 A . Prior to 1920 ................................. 414 B . 1920 - 1940 .................................. 418 C. 1940 - 1980 .................................. 421 D . 1980 - Present ................................ 425 Ill. PRESERVATION OF RAIL-RAIL COMPETITION AS A CONSIDERATION IN THE FORMATION OF CONRAIL AND SUBSEQUENT DETERMINATION TO SELL CONRAIL ........ ........................................ 428 A. 1970's Congressional Response to the Penn Central and Other Railroad Bankruptcies ..................... 428 B. Foundation of Initial CongressionalPolicy ........... 429 C. Implementing the Policy ........................ -

ALLEGHANY CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K þ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2015 or ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 1-9371 ALLEGHANY CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 51-0283071 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 7 Times Square Tower, New York, New York 10036 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 212-752-1356 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange Title of Each Class on Which Registered Common Stock, $1.00 par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Not applicable Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes þ No ¨ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No þ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Corporate Records Subseries 1—Akron & Barberton Belt Railroad

The John W. Barriger III Papers- Series 1- Corporate Records Subseries 1—Akron & Barberton Belt Railroad Company Subseries 2—Akron, Canton & Youngstown Railroad Company Subseries 3—Alabama Great Southern Railroad Subseries 4—Alabama, Tennessee & Northern Railroad Subseries 5—Alaska Railroad Subseries 6—Algoma Central & Hudson Bay Railway Company Subseries 7—Alleghany Corporation Subseries 8—Alton and Southern Railroad Subseries 9—Alton Railroad Company Subseries 10—American Railroad Company of Porto Rico Subseries 11—Amoskeag Company Subseries 12—Amtrak (National Railroad Passenger Corporation) Subseries 13—Ann Arbor Railroad Company Subseries 14—Apache Railway Company Subseries 15—Ashley, Drew & Northern Railway Company Subseries 16—Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Subseries 17—Atlanta & St. Andrew’s Bay Railway Subseries 18—Atlanta and West Point Railroad Company Subseries 19—Atlanta, Birmingham and Coast Railroad Company Subseries 20—Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad Subseries 21—Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Subseries 22—Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Subseries 23—Baltimore & Sparrows Point Railroad Subseries 24—Baltimore, Chesapeake & Atlantic Railway Subseries 25—Bangor & Aroostook Railroad Subseries 26—Bangor Punta Subseries 27—Barnegat Railroad Company Subseries 28—Beech Creek Railroad Company Subseries 29—Bellefonte Central Railroad Company Subseries 30—Belt Railway Company of Chicago Subseries 31—Bessemer and Lake Erie Railroad Company Big Four Route—see Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Ry. Subseries 32—Bingham and -

SEC News Digest, 05-05-1982

_________________ ==U.:.!.S>!.!.C-.lo!S:"'E.\oIC"-lll~R>.LITLJII.I:.E.:;S__AA.AlN.g.D • ._. __ ... _ •. _ EXCHANGE COMMISSION CMl PROCEEDINGS -------~------------------_. __ ._._-- -------- STEVEN R. GRAYSON PRELIMINARILY ENJOINED The Los Angeles Regional Office announced that on April 26 the Honorable Cynthia H. Hall, U.S. District Judge for the Central District of California, issued a prelimi- nary injunction against Steven R. Grayson which, among other things, prohibits him from committiRg further violations of the antifraud provisions of the securities laws, and transferring or dissipating assets while the Court's Order is in effect. The Court found that Grayson, a municipal securities salesman, had violated Section 17(a) (1) and (2) of the Securities Act of 1933, Section lOeb) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-S thereunder, in connection with the offer and sale of municipal bonds. Specifically, the Court found that Grayson had obtained from his employer $150,000 worth of municipal bearer bonds through a fraudulent representation that he planned to deliver them to a customer. In fact, Grayson neither delivered the bonds to the customer nor returned them to the firm. In addition, the court found that Grayson had induced his retail customers to turn over to him at least $1.6 million worth of municipal bearer bonds on the represen- tation that he would upgrade the bonds and return them to the customers. Instead, the bonds were sold through a nominee account and neither the proceeds of the sales nor any new bonds were returned to the customers. -

Alleghany Corporation

ALLEGHANY CORP /DE FORM 10-Q (Quarterly Report) Filed 05/07/07 for the Period Ending 03/31/07 Address 7 TIMES SQUARE TOWER 17TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10036 Telephone 212-752-1356 CIK 0000775368 Symbol Y SIC Code 6331 - Fire, Marine, and Casualty Insurance Industry Insurance (Prop. & Casualty) Sector Financial Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2014, EDGAR Online, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, Inc. Terms of Use. ALLEGHANY CORP /DE FORM 10-Q (Quarterly Report) Filed 5/7/2007 For Period Ending 3/31/2007 Address 375 PARK AVENUE SUITE 3201 NEW YORK, New York 10152 Telephone 212-752-1356 CIK 0000775368 Industry Conglomerates Sector Conglomerates Fiscal Year 12/31 Table of Contents SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q (MARK ONE) QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR QUARTERLY PERIOD ENDED MARCH 31, 2007 TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD ENDING COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 1-9371 ALLEGHANY CORPORATION EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER DELAWARE STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF INCORPORATION OR ORGANIZATION 51-0283071 INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NUMBER 7 TIMES SQUARE TOWER, 17TH FLOOR, NY, NY 10036 ADDRESS OF PRINCIPAL EXECUTIVE OFFICE, INCLUDING ZIP CODE 212-752-1356 REGISTRANT’S TELEPHONE NUMBER, INCLUDING AREA CODE NOT APPLICABLE FORMER NAME, FORMER ADDRESS, AND FORMER FISCAL YEAR, IF CHANGED SINCE LAST REPORT INDICATE BY CHECK MARK WHETHER THE REGISTRANT (1) HAS FILED ALL REPORTS REQUIRED TO BE FILED BY SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 DURING THE PRECEDING 12 MONTHS (OR FOR SUCH SHORTER PERIOD THAT THE REGISTRANT WAS REQUIRED TO FILE SUCH REPORTS), AND (2) HAS BEEN SUBJECT TO SUCH FILING REQUIREMENTS FOR THE PAST 90 DAYS.