THE MANAGEMENT of INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS at UC BERKELEY: Turning Points and Consequences*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

BANCROFTIANA Number 145 • University of California, Berkeley • Fall 2014

Newsletter of The Friends of The Bancroft Library BANCROFTIANA Number 145 • University of California, Berkeley • Fall 2014 CALIFORNIA Captured On Canvas alifornia Captured on Canvas represents a first for The John superseded John Singer Sargent as the most important CBancroft Library Gallery. The exhibit focuses exclu- and fashionable portrait painter in England. As famous for sively on the Pictorial Collection’s more than 300 paintings. his bohemian life as he was for his bravura portraits, John With the exception of the 120 framed works in the Robert is said to have been the model for Alec Guinness’s character B. Honeyman, Jr. Collection of Early Californian and West- Gulley Jimson in the film The Horse’s Mouth. (Interestingly, ern American Pictorial Material—acquired by the Friends of John painted both T. E. Lawrence’s and King Faisal’s por- The Bancroft Library and the UC Regents in 1963—most of traits. Alec Guinness portrayed Faisal in David Lean’s epic the impressive array of framed works in the Pictorial Collec- film, Lawrence of Arabia.) tion are the result of individual donations or transfers from The inclusion of John Sackas’s colorful paintings collections acquired by gift or purchase. These works range documenting the Golden Gate Produce Market in the late not only in subject matter and geography—portraits from 1950s, before it was torn down in 1962 to make way for the Mexico, landscapes of Utah and the American Southwest— Embarcadero Center, and a study for a mural by Carleton but they also vary in medium from delicate pencil sketches, Lehman, painted on the verso of his portrait of Inez Ghi- watercolors, gouaches, ink and wash drawings, engravings, rardelli, expands the scope of this exhibition beyond the hand-colored lithographs, and photographs to oils on Continued on page 4 canvas, board, and paper. -

2005-06 GOLDEN BEAR FACTS/ROSTER BEAR FACTS TABLE of CONTENTS Location: Berkeley, CA 94720 Founded: 1868 a Look at the Golden Bears

2005-06 GOLDEN BEAR FACTS/ROSTER BEAR FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location: Berkeley, CA 94720 Founded: 1868 A Look at the Golden Bears ....................................................... 2-3 Enrollment: 33,000 Scouting Report .............................................................................. 4 Colors: Blue (282) & Gold (116) Golden Bear Notes ...................................................................... 5-8 Nickname: Golden Bears 2006 NCAA Tournament Bracket ................................................ 9 Chancellor: Dr. Robert Birgeneau Cal vs. NCAA Tournament Field ................................................ 10 Athletic Director: Sandy Barbour Arena: Walter A. Haas Jr. Pavilion (11,877) Cal in Postseason Play ............................................................ 11-13 Conference: Pacific-10 NCAA Tournament Records .................................................. 14-15 NCAA Tournament Appearances: 14 Head Coach Ben Braun ........................................................... 16-17 1946, ’57, ’58, ’59, ’60, ’90, ’93, ’94, ’96, ’97, 2001, ’02, ’03, ’06 Assistant Coaches ........................................................................ 18 NCAA Final Four Appearances: 3 2005-06 Player Profiles .......................................................... 19-32 1946 (4th), 1959 (1st), 1960 (2nd) Pacific-10 Standings & Honors .................................................... 33 2005-06 Record: 20-10 2005-06 Pac-10 Record/Finish: 12-6/3rd 2005-06 Cumulative Stats ........................................................... -

Download This Issue As A

MICHAEL GERRARD ‘72 COLLEGE HONORS FIVE IS THE GURU OF DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI CLIMATE CHANGE LAW WITH JOHN JAY AWARDS Page 26 Page 18 Columbia College May/June 2011 TODAY Nobel Prize-winner Martin Chalfie works with College students in his laboratory. APassion for Science Members of the College’s science community discuss their groundbreaking research ’ll meet you for a I drink at the club...” Meet. Dine. Play. Take a seat at the newly renovated bar grill or fine dining room. See how membership in the Columbia Club could fit into your life. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 26 20 30 18 73 16 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 2 20 A PA SSION FOR SCIENCE 38 B OOKSHELF LETTERS TO THE Members of the College’s scientific community share Featured: N.C. Christopher EDITOR Couch ’76 takes a serious look their groundbreaking work; also, a look at “Frontiers at The Joker and his creator in 3 WITHIN THE FA MILY of Science,” the Core’s newest component. Jerry Robinson: Ambassador of By Ethan Rouen ’04J, ’11 Business Comics. 4 AROUND THE QU A DS 4 Reunion, Dean’s FEATURES 40 O BITU A RIES Day 2011 6 Class Day, 43 C L A SS NOTES JOHN JA Y AW A RDS DINNER FETES FIVE Commencement 2011 18 The College honored five alumni for their distinguished A LUMNI PROFILES 8 Senate Votes on ROTC professional achievements at a gala dinner in March. -

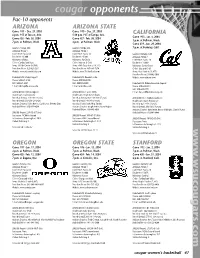

100709 WBB MG Text.Id2

cougar opponents Pac-10 opponents ARIZONA ARIZONA STATE Game #11 – Dec. 29, 2003 Game #10 – Dec. 27, 2003 6 p.m. PST at Tucson, Ariz. 5:30 p.m. PST at Tempe, Ariz. CALIFORNIA Game #13 - Jan. 4, 2004 Game #26 - Feb. 26, 2004 Game #27 - Feb. 28, 2004 1 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. 7 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. 2 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. Game #19 – Jan. 29, 2004 Location: Tucson, Ariz. Location: Tempe, Ariz. 7 p.m. at Berkeley, Calif. Affiliation: NCAA 1 Affiliation: NCAA 1 Conference: Pacific-10 Conference: Pacific-10 Location: Berkeley, Calif. Enrollment: 35,000 Enrollment: 45,693 Affiliation: NCAA 1 Nickname: Wildcats Nickname: Sun Devils Conference: Pacific-10 Colors: Cardinal and Navy Colors: Maroon & Gold Enrollment: 33,000 Arena: McKale Center (14,545) Arena: Wells Fargo Arena (14,141) Nickname: Golden Bears Press Row Phone: 520-621-5291 Press Row Phone: 480-965-7274 Colors: Blue and Gold Website: www.arizonaathletics.com Website: www.TheSunDevils.com Arena: Haas Pavilion (11,877) Press Row Phone: 510-642-3098 Basketball SID: Mindy Claggett Basketball SID: Rhonda Lundin Website: www.calbears.com Phone: 520-621-4163 Phone: 480-965-9780 FAX: 520-621-2681 FAX: 480-965-5408 Basketball SID: Debbie Rosenfeld-Caparaz E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 510-642-3611 FAX: 510-643-7778 Athletic Director: Jim Livengood Athletic Director: Gene Smith E-mail: [email protected] Head Coach: Joan Bonvicini Head Coach: Charli Turner Thorne Record at Arizona: 214-139 (12 years) Record at Arizona State: 106-100 (7 years) Athletic -

Centralia Couple Charged After Years of Alleged Neglect and Abuse; Child, 16, Weighed 54 Pounds COURT DOCUMENTS: Medical Staff a Centralia Couple Made Their First S

Can You Hear $1 Me Now? Weekend Edition Cell Service Saturday, Debated Dec. 31, 2016 at Rainier Serving our communities since 1889 — www.chronline.com / Life 1 Swearing an Oath Interstate 5 Cold Case Fund, Jackson Sworn in After Victories in State Patrol Still Seeking Leads in Road Rage County Commission Campaigns / Main 10 Shooting That Occurred One Year Ago / Main 5 Centralia Couple Charged After Years of Alleged Neglect and Abuse; Child, 16, Weighed 54 Pounds COURT DOCUMENTS: Medical Staff A Centralia couple made their first S. Foxworth Sr, 44, made their first ap- a child in their care by “withholding any court appearance Friday on charges al- pearances out of custody in Lewis Coun- of the basic necessities of life,” according Disturbed by State of Teen Who leging that they severely neglected a child ty Superior Court Friday on suspicion of to charging documents. Had Not Eaten in Weeks or in their care for a period of approximate- first-degree criminal mistreatment, do- Both were granted $10,000 unsecured Seen a Doctor in Nine Years ly nine years, leading to serious medical mestic violence. bail, allowing them to remain out of po- issues and delayed physical and mental It is alleged that between January lice custody. They were appointed attor- neys Friday. By Natalie Johnson development. 2007 and January 2016, the Foxworths [email protected] Mary G. Foxworth, 42, and Anthony recklessly caused “great bodily harm” to please see NEGLECT, page Main 12 Judge County 911 Dispatchers Advised to Wear Dismisses Masks After Water Leaks, Mold Growth Rape Case After Deputy’s Conduct During Trial MISTRIAL: Lewis County Deputy Accused of Trying to Influence Testimony of Victim By Natalie Johnson [email protected] A jury will not have the opportunity to deliver a ver- dict in a rape case after a judge ruled this month that a deputy from the Lewis Coun- ty Sheriff’s Office engaged in “governmental misconduct” during a trial. -

Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Bob Steiner Bob Steiner: Oral Histories on the Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960 - 2014 Interviews conducted by John C. Cummins in 2013 Copyright © 2017 by The Regents of the University of California ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Bob Steiner dated January 27, 2016. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Annual Report 2009–2010 Columbia University Columbia 2009–2010 Report Annual Nstitute

WEATHERHEAD ANNUAL REPORT 2009 – 2 010 E AST A SIAN I NSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT 2009–2010 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Weatherhead East Asian Institute Columbia University International Affairs Building, 9th floor MC 3333 420 West 118th Street New York, NY 10027 Tel: 212-854-2592 Fax: 212-749-1497 www.columbia.edu/weai TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR 1 2 THE WEATHERHEAD EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE AT COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2 3 THE RESEARCH COMMUNITY 3 4 PUBLICATIONS 26 5 RESEARCH CENTERS AT THE WEATHERHEAD EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE AND AFFILIATED COLUMBIA PROGRAMS 30 6 PUBLIC PROGRAMMING 34 7 GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES 39 8 STUDENTS 43 9 ASIA FOR EDUCATORS PROGRAM 47 10 AdMINISTRATIVE STAFF OF THE WEATHERHEAD EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE 50 11 FUNDING SOURCES 51 12 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY MAP: MORNINGSIDE CAMPUS & ENVIRONS 52 1 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Over the past year, the Weatherhead East Asian Institute’s leading position in regional studies was amply reaffirmed. A fitting finale to our 60th anniversary celebrations was the June 13, 2010, symposium in Taipei, “Taiwan in the Twenty-first Century: Politics, Economy and Society.” This symposium continued WEAI’s outreach programs in East Asia to local Columbia alumni and to all prior visiting scholars, professional fellows, or participants at WEAI. The first three symposia were held in Beijing, Tokyo, and Seoul during May and June of 2009, and planning is now under way for a May 2011 sym- posium to take place in Hong Kong. As with the earlier events, the Taipei symposium involved close cooperation with the Columbia Alumni Association. The local signifi- cance of the symposium was underscored by the keynote speaker, Vincent Siew, vice president of the Republic of China (Taiwan), and by the meeting on the following day of symposium panelists and speakers with ROC President Ma Ying-jeou. -

History of the Clark Kerr Award

HISTORY OF THE CLARK KERR AWARD In 1968, the Berkeley Division of the Academic Senate created the Clark Kerr Award as a tribute to the leadership and legacy of President Emeritus Kerr. The Clark Kerr Award recognizes an individual who has made an extraordinary and distinguished contribution to the advancement of higher education. Past recipients have come from inside and outside the Berkeley community, including former California Governor and Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, and past Chancellors Ira Michael Heyman and Chang-Lin Tien. 1968 CLARK KERR 1996 Sanford H. Kadish 1969 J. E. Wallace Sterling Philip Selznick 1970 Sir Eric Ashby 1997 Chang-Lin Tien 1971 Roger W. Heyns 1998 Yuan T. Lee 1972 Earl Warren 2000 Herbert F. York 1973 Theodore M. Hesburgh 2002 John Hope Franklin 1974 John W. Gardner 2004 Lee C. Bollinger 1976 Elinor Raas Heller 2005 Jack W. Peltason 1977 James B. Conant 2006 Nannerl O. Keohane 1979 Choh-Ming Li 2007 Karl S. Pister 1980 Joel H. Hildebrand 2008 Harold T. Shapiro 1981 Richard W. Lyman 2009 Charles E. Young 1982 Lynn White Jr. 2010 William G. Bowen 1983 David Riesman 2012 Robert M. Berdahl 1984 Sanford S. Elberg Marian C. Diamond 1985 Lord Noel Gilroy Annan 2013 Ricardo Romo 1986 Glenn T. Seaborg 2014 Marye Anne Fox 1987 Robert E. Marshak 2015 Hanna Holborn Gray 1988 Morrough P. O’Brien 2016 George W. Breslauer Lincoln Constance 2017 Mary Sue Coleman Ewald T. Grether 2018 Richard C. Atkinson Harry R. Wellman C. Judson King III 1989 J. William Fulbright 2019 Freeman A. -

Pac-10 Conference Pac-12 Conference

PAC-10 CONFERENCE PAC-12 CONFERENCE 1350 Treat Blvd., Suite 500, Walnut Creek, CA 94597 // PAC-12.COM // 925.932.4411 For Immediate Release: August 27, 2012 Contacts: Dave Hirsch ([email protected]), Alex Kaufman ([email protected]) 2012 PAC-12 FOOTBALL STANDINGS PAC-12 OVERALL NORTH W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. PF PA Home Road Neut. vs. Div Streak California 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Oregon 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Oregon State 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Stanford 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Washington 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Washington State 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 SOUTH W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. PF PA Home Road Neut. vs. Div Streak Arizona 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Arizona State 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Colorado 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 UCLA 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 USC 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Utah 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 This Week’s Schedule Thurs., Aug. -

2018 Cal Football Record Book.Pdf

CALIFORNIA GOLDEN BEARS FOOTBALL TABLE OF CONTENTS Media Info .................................................................1 2018 Year In Review ..............................................12 Records ..................................................................42 History .....................................................................70 This Is Cal ............................................................ 120 2018 PRESEASON CALIFORNIA FOOTBALL NOTES WILCOX BEGINS SECOND SEASON IN 2018 CAL IN SEASON OPENERS • Justin Wilcox is in his second season as the head football coach at • Cal opens the 2018 season in Berkeley when the Bears host North Cal in 2018. After leading some of the top defenses in the nation as Carolina in the second-ever meeting ever between the teams. Cal won an FBS defensive coordinator for 11 seasons prior to his arrival at the first meeting, 35-30, in the 2017 season-opener in Chapel Hill, Cal in January of 2017, Wilcox posted a 5-7 overall mark in his first N.C. The Bears have won their last season openers. campaign at the helm of the Golden Bears. • The highlights of his first season as the head coach in Berkeley in NATIONAL HONORS CANDIDATE PATRICK LAIRD 2017 included a 3-0 start that featured wins over North Carolina and • Running back Patrick Laird is a national honors candidate and on Ole Miss, as well as a 37-3 victory over then No. 8/9 Washington State the preseason watch list for the Maxwell Award given annually to in an ESPN nationally-televised Friday night home game. The victory America's College Football Player of the Year in 2018 after a breakout against the Cougars snapped Cal's 17-game losing streak to top-10 2017 junior season when he earned honorable mention All-Pac-12 teams, was the Bears' first victory against a top-10 team since 2003 honors and was one of 10 national semifinalists for the Burlsworth and only its second top-10 win since 1977. -

The Student Uprising That Ushered in the Radical Sixties: the Berkeley Free Speech Movement

The Student Uprising That Ushered In the Radical Sixties: The Berkeley Free Speech Movement Book Review: Hal Draper, Berkeley, The New Student Revolt. Haymarket, 2020. Thomas Harrison The current mass upheaval has reached a scale not seen in this country since the 1960s. So it is timely that Haymarket Books has republished an account of one of the key revolts in that fabled decade – the 1964 Free Speech Movement (FSM) at the University of California at Berkeley. Originally issued by Grove Press in 1965 and published in a second edition in 2010 by the Center for Socialist History, Hal Draper’s book remains the most vivid narrative and incisive analysis of the FSM that I know. A Marxist scholar of immense learning and a veteran of the revolutionary socialist movement, he was also a deeply involved participant in the FSM itself. Indeed, Draper’s influence led UC President Clark Kerr to call him, hyperbolically, “the chief guru of the FSM.” Berkeley, The New Student Revolt recommends itself to all those interested in the history of protest and the left in this country, but especially, I think, to the young radicals and socialists who are today immersed in the great multiracial movement against racism and police violence and for fundamental social change. Draper became a Trotskyist in the 30s. He was part of the tendency led by Max Shachtman that split from the Trotskyists in 1940 in a dispute over the nature of the Soviet Union and formed the Workers Party. The group, which changed its name to the Independent Socialist League (ISL) in 1949, stood for what it called the Third Camp, in opposition to both capitalism and the “bureaucratic collectivism” of the Soviet Bloc and Communist China.