Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

2005-06 GOLDEN BEAR FACTS/ROSTER BEAR FACTS TABLE of CONTENTS Location: Berkeley, CA 94720 Founded: 1868 a Look at the Golden Bears

2005-06 GOLDEN BEAR FACTS/ROSTER BEAR FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location: Berkeley, CA 94720 Founded: 1868 A Look at the Golden Bears ....................................................... 2-3 Enrollment: 33,000 Scouting Report .............................................................................. 4 Colors: Blue (282) & Gold (116) Golden Bear Notes ...................................................................... 5-8 Nickname: Golden Bears 2006 NCAA Tournament Bracket ................................................ 9 Chancellor: Dr. Robert Birgeneau Cal vs. NCAA Tournament Field ................................................ 10 Athletic Director: Sandy Barbour Arena: Walter A. Haas Jr. Pavilion (11,877) Cal in Postseason Play ............................................................ 11-13 Conference: Pacific-10 NCAA Tournament Records .................................................. 14-15 NCAA Tournament Appearances: 14 Head Coach Ben Braun ........................................................... 16-17 1946, ’57, ’58, ’59, ’60, ’90, ’93, ’94, ’96, ’97, 2001, ’02, ’03, ’06 Assistant Coaches ........................................................................ 18 NCAA Final Four Appearances: 3 2005-06 Player Profiles .......................................................... 19-32 1946 (4th), 1959 (1st), 1960 (2nd) Pacific-10 Standings & Honors .................................................... 33 2005-06 Record: 20-10 2005-06 Pac-10 Record/Finish: 12-6/3rd 2005-06 Cumulative Stats ........................................................... -

North Carolina Basketball Former Head Coach Dean Smith

2001-2002 NORTH CAROLINA BASKETBALL FORMER HEAD COACH DEAN SMITH When ESPN’s award-winning Sports Century program in at least one of the two major polls four times (1982, selected the greatest coaches of the 20th Century, it came 1984, 1993 and 1994). to no surprise that Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith • Smith’s teams were also the dominant force in the was among the top seven of alltime. Smith joined other Atlantic Coast Conference. The Tar Heels under Smith had legends Red Auerbach, Bear Bryant, George Halas, Vince a record of 364-136 in ACC regular-season play, a winning Lombardi, John McGraw and John Wooden as the preem- percentage of .728. inent coaches in sports history. • The Tar Heels finished at least third in the ACC regu- Smith’s tenure as Carolina basketball coach from 1960- lar-season standings for 33 successive seasons. In that 97 is a record of remarkable consistency. In 36 seasons at span, Carolina finished first 17 times, second 11 times and UNC, Smith’s teams had a record of 879-254. His teams third five times. won more games than those of any other college coach in • In 36 years of ACC competition, Smith’s teams fin- history. ished in the conference’s upper division all but one time. However, that’s only the beginning of what his UNC That was in 1964, when UNC was fifth and had its only teams achieved. losing record in ACC regular-season play under Smith at • Under Smith, the Tar Heels won at least 20 games for 6-8. -

Vanderbilt Commodores (0-2, 0-1) #4/5 LSU (3-0, 0-0)

Vanderbilt Commodores Sept. 21, 2019 • 11 a.m. CT 0-2 overall • 0-1 SEC East Vanderbilt Stadium • Nashville, Tenn. • 40,350 Date Opponent Time • Result SEC Network 8.31 #3/3 Georgia*...................................................L, 6-30 Vanderbilt Commodores (0-2, 0-1) Tom Hart (play-by-play), Jordan Rodgers (analyst), 9.7 at Purdue .......................................................L, 24-42 #4/5 LSU (3-0, 0-0) Cole Cobelic (sideline) 9.21 #4/5 LSU* [SEC Network] ...............................11 a.m. 9.28 Northern Illinois .................................................. TBA VUCommodores.com WLAC 1510 AM / WNRQ FM 98.3 10.5 at Ole Miss* ......................................................... TBA • @VandyFootball Twitter Joe Fisher (play-by-play), Norman Jordan (analyst), 10.12 UNLV .................................................................... TBA @VandyFootball Instagram • Mitch Light (sideline) 10.19 Missouri* (Homecoming) .................................... TBA Facebook • VanderbiltAthletics 11.2 at South Carolina* ............................................... TBA In-Game Notes • @VandyNotes Primary Football Contact • Larry Leathers 11.9 at Florida* ............................................................ TBA [email protected] • 615.480.8226 11.16 Kentucky* ............................................................ TBA 11.23 East Tennessee State .......................................... TBA Secondary Football Contact • Andrew Pate 11.30 at Tennessee* ..................................................... -

Fall, 2006 What Football Coach Said, “Winning Tenn

Memorial Completed - See page 2 ILITARY M A IA C B A M D U E L M O Y C • A • QUI SE VINC IT N L IT V I NC U O I BUGLE M QUARTERLY N AT I ASSOCI Volume 6, Number 3 Fall, 2006 What Football Coach Said, “Winning Tenn. Tech Ad. Building “100 Years of Tradition” Isn’t Everything, It’s the Only Thing!” Dedicated to CMA Grad VHS/DVD Still Available The Tennessee Technology Center Almumni If you said Vince Lombardi you U.C.L.A.,” relates Hall. “My years at CMA at Oneida/Huntsville, TN, dedicated its would be wrong. Vince said something were probably the most important of new administration building to long time similar but it was another football my youth as my time helped mold the state Senator George Alvin Terry, Class great, Coach Henry R. “Red” Sanders character I carried through life.” He re- of ‘44. The December dedication was at- (1905-1958), who coached the CMA members that CMA got a lot of publicity tended by a number of CMA graduates. Bulldogs from 1930 to 1934 who first during Sanders stay, which included a George and his brother both attended CMA in the ‘40s. He has several grown Photos supplied by Tony Woolwine, Class of ‘56 uttered those words according to Scoop lot of national attention among private Hudgins, Vanderbilt’s sports information schools. daughters and resides in Goodlettsville, director from 1946 to 1948 and Fred TN with his wife Sarah. Russell, retired sports editor of the Clemson before moving to Columbia. -

Media Guide Cover.Indd

University of Iowa Football 2007 Media Fact Book TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents _____________________________________ 1 Iowa Bowl Records/Results ___________________________ 114 Football Facts and Information __________________________ 2 Iowa In The National Rankings _____________________115-117 Sally Mason/Gary Barta ________________________________ 3 National Awards _________________________________118-119 Head Coach - Kirk Ferentz _____________________________4-5 Consensus All-Americans __________________________120-121 Offensive Coordinator - Ken O’Keefe ______________________ 6 Retired Numbers/Hall of Fame/Varsity Club Hall of Fame ____ 122 Defensive Coordinator - Norm Parker _____________________ 7 All-Time Team ______________________________________ 123 Receivers & Special Teams Coach - Lester Erb ______________ 8 First Team All-Americans _____________________________ 124 Running Backs Coach - Carl Jackson ______________________ 9 Second Team All-Americans ___________________________ 125 Tight Ends Coach & Recruiting Coordinator - Eric Johnson ___ 10 Academic All-Americans and Academic All-Big Ten ________ 126 Defensive Line Coach - Rick Kaczenski ___________________ 11 All-Big Ten/MVPs/Lineman of the Year _________________ 127 Offensive Line Coach - Reese Morgan ____________________ 12 Iowa MVPs _________________________________________ 128 Defensive Backs Coach - Phil Parker _____________________ 13 Iowa Captains ______________________________________ 129 Outside Linebackers & Special Teams Coach - Darrell Wilson ___ 14 NFL -

2017-18 Big Ten Records Book

2017-18 BIG TEN RECORDS BOOK Big Life. Big Stage. Big Ten. BIG TEN CONFERENCE RECORDS BOOK 2017-18 70th Edition FALL SPORTS Men’s Cross Country Women’s Cross Country Field Hockey Football* Men’s Soccer Women’s Soccer Volleyball WINTER SPORTS SPRING SPORTS Men's Basketball* Baseball Women's Basketball* Men’s Golf Men’s Gymnastics Women’s Golf Women’s Gymnastics Men's Lacrosse Men's Ice Hockey* Women's Lacrosse Men’s Swimming and Diving Rowing Women’s Swimming and Diving Softball Men’s Indoor Track and Field Men’s Tennis Women’s Indoor Track and Field Women’s Tennis Wrestling Men’s Outdoor Track and Field Women’s Outdoor Track and Field * Records appear in separate publication 4 CONFERENCE PERSONNEL HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS Faculty Representatives Basketball Coaches - Men’s 1997-2004 Ron Turner 1896-1989 Henry H. Everett 1906 Elwood Brown 2005-2011 Ron Zook 1898-1899 Jacob K. Shell 1907 F.L. Pinckney 2012-2016 Tim Beckman 1899-1906 Herbert J. Barton 1908 Fletcher Lane 2017- Lovie Smith 1906-1929 George A. Goodenough 1909-1910 H.V. Juul 1929-1936 Alfred C. Callen 1911-1912 T.E. Thompson Golf Coaches - Men’s 1936-1949 Frank E. Richart 1913-1920 Ralph R. Jones 1922-1923 George Davis 1950-1959 Robert B. Browne 1921-1922 Frank J. Winters 1924 Ernest E. Bearg 1959-1968 Leslie A. Bryan 1923-1936 J. Craig Ruby 1925-1928 D.L. Swank 1968-1976 Henry S. Stilwell 1937-1947 Douglas R. Mills 1929-1932 J.H. Utley 1976-1981 William A. -

ALL-TIME Yearly RECORDS

ALL-TIME YEARLY RECORDS Year W L T Head Coach Year W L T Head Coach 1890 1 0 - Elliott H. Jones 1953 3 7 - Art Guepe MCGUGIN 1891 3 1 - Elliott H. Jones 1954 2 7 - Art Guepe A native of Iowa and 1892 4 4 - Elliott H. Jones 1955 8 3 - Art Guepe Michigan graduate, 1893 6 1 - W.J. Keller 1956 5 5 - Art Guepe Dan McGugin 1894 7 1 - Henry Thornton 1957 5 3 2 Art Guepe coached Vanderbilt 1895 5 3 1 C.L. Upton 1958 5 2 3 Art Guepe for three decades, 1896 3 2 2 R.G. Acton 1959 5 3 2 Art Guepe compiling a 1897 6 0 1 R.G. Acton 1960 3 7 - Art Guepe 1898 1 5 - R.G. Acton 1961 2 8 - Art Guepe 197-55-19 overall 1899 7 2 - J.L. Crane 1962 1 9 - Art Guepe record. He is a 1900 4 4 1 J.L. Crane 1963 1 7 2 Jack Green member of the 1901 6 1 1 W.H. Watkins 1964 3 6 1 Jack Green College Football 1902 8 1 - W.H. Watkins 1965 2 7 1 Jack Green Hall of Fame. 1903 6 1 1 J.H. Henry 1966 1 9 - Jack Green 1904 9 0 - Dan McGugin 1967 2 7 1 Bill Pace 1905 7 1 - Dan McGugin 1968 5 4 1 Bill Pace ALL-TIME COACHING RECORDS 1906 8 1 - Dan McGugin 1969 4 6 - Bill Pace 1907 5 1 1 Dan McGugin 1970 4 7 - Bill Pace Head Coach Years W L T 1908 7 2 1 Dan McGugin 1971 4 6 1 Bill Pace Elliott H. -

The NCAA News

The NCAA April 10,198s. Volume 22 Number IS Offkial Publication oft ational Collegiate Athletic Association Survev reflects CEOs’ concern about integrity J Chief executive officers of NCAA sults of a study conducted for the overall response rate was 60 percent. provided by the research organization cerned about the degree of institu- member institutions are deeply con- NCAA Presidents’ Commission by “The high rate surely reflects intense appears in a special pull-out section tional control being exercised over cerned about the current state of the American Institutes for Research concern on the part of CEOs with the (pages 5 through U) in this issue of college athletics programs (99 percent integrity in mtercollegiate athletics, (AIR). issues that prompted the survey,” said The NCAA News. in Division I-A). according to what appears to be the Results of the survey and the Presi- Steven M. Jung, AIR’s principal re- Specific integrity problems identi- most comprehensive and definitive dents’ Commission’s decisions regard- search scientist who served as project Integrity issues fied as serious by at least 60 percent of national survey of presidential views ing legislation it will sponsor at the director m Palo Alto, California. Of all respondents, 99 percent are the respondents were inducements to regarding athletics ever taken. special NCAA Convention in June Included in the response rate were very much or moderately concerned prospective student -athletes (75 per- ‘The CEOs’ concerns regarding the (see story on this page) were an- 75 percent of all Division I-A CEOs, by the current state of intrgrity in cent), the academic performance of integrity of college athletics, its effect nounced April 5 at a press conference 74 percent in I-AA, 64 percent in I- athletics and the possible damage enrolled student-athletes (62 percent) on the Image of higher education and in Washington, D.C. -

2016-17 Game Notes

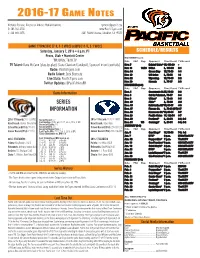

2016-17 GAME NOTES Nicholas Petrone, Director of Athletic Media Relations [email protected] O: 209-946-2730 www.PacificTigers.com C: 660-888-3275 3601 Pacific Avenue, Stockton, CA 95211 GAME 17/PACIFIC (7-9, 1-2 WCC) at BYU (11-5, 2-1 WCC) Saturday, January 7, 2016 • 6 p.m. PT SCHEDULE/RESULTS Provo, Utah • Marriott Center NOVEMBER (2-3) TV: BYUtv, TheW.TV Date PAC Opp. Opponent Time/Result TV/Record TV Talent: Dave McCann (play-by-play), Steve Cleveland (analyst), Spencer Linton (courtside) Nov. 7 Bristol Univ.^ W, 106-39 - Radio: PacificTigers.com Nov. 11 16/20 UCLA L, 119-80 0-1 Nov. 14 Green Bay W, 76-58 1-1 Radio Talent: Zack Bayrouty Nov. 19 UC Irvine L, 72-65 1-2 Live Stats: PacificTigers.com Nov. 22 Wyoming W, 73-65 2-2 Twitter Updates: @PacificMensBB Nov. 29 Nevada L, 77-67 2-3 DECEMBER (4-6) Date PAC Opp. Opponent Time/Result TV/Record Game Information Dec. 1 Sacramento St. W, 74-58 3-3 Dec. 3 Cal St. Fullerton L, 78-77 3-4 Dec. 8 UMass” L, 72-48 3-5 SERIES Dec. 10 Rider” L, 73-66 3-6 Dec. 15 North Carolina A&T” W, 66-57 4-6 INFORMATION Dec. 17 Fresno St. L, 70-68 (OT) 4-7 Dec. 20 Kennesaw St.” W, 69-56 5-7 Dec. 23 Pacific Union W, 102-54 6-7 2016-17 Record: 7-9, 1-2 WCC Series Record: 5-7 2016-17 Record: 11-5, 2-1 WCC Dec. -

09FB Guide P163-202 Color.Indd

CCALAL HHISTORYISTORY JJACKIEACKIE JJENSENENSEN CCalal HHallall ooff FFame,ame, CClasslass ooff 11986986 CALIFORNIA GOLDEN BEARS FootballFtbllIf Information tiGid Guide 163163 HISTORY OF CAL FOOTBALL, YEAR-BY-YEAR YEAR –––––OVERALL––––– W L T PF PA COACH COACHING SUMMARY 1886 6 2 1 88 35 O.S. Howard COACH (YEARS) W L T PCT 1887 4 0 0 66 12 None O.S. Howard (1886) 6 2 1 .722 1888 6 1 0 104 10 Thomas McClung (1892) 2 1 1 .625 1890 4 0 0 45 4 W.W. Heffelfi nger (1893) 5 1 1 .786 1891 0 1 0 0 36 Charles Gill (1894) 0 1 2 .333 1892 Sp 4 2 0 82 24 Frank Butterworth (1895-96) 9 3 3 .700 1892 Fa 2 1 1 44 34 Thomas McClung Charles Nott (1897) 0 3 2 .200 1893 5 1 1 110 60 W.W. Heffelfi nger Garrett Cochran (1898-99) 15 1 3 .868 1894 0 1 2 12 18 Charles Gill Addison Kelly (1900) 4 2 1 .643 Nibs Price 1895 3 1 1 46 10 Frank Butterworth Frank Simpson (1901) 9 0 1 .950 1896 6 2 2 150 56 James Whipple (1902-03) 14 1 2 .882 1897 0 3 2 8 58 Charles P. Nott James Hooper (1904) 6 1 1 .813 1898 8 0 2 221 5 Garrett Cochran J.W. Knibbs (1905) 4 1 2 .714 1899 7 1 1 142 2 Oscar Taylor (1906-08) 13 10 1 .563 1900 4 2 1 53 7 Addison Kelly James Schaeffer (1909-15) 73 16 8 .794 1901 9 0 1 106 15 Frank Simpson Andy Smith (1916-25) 74 16 7 .799 1902 8 0 0 168 12 James Whipple Nibs Price (1926-30) 27 17 3 .606 1903 6 1 2 128 12 Bill Ingram (1931-34) 27 14 4 .644 1904 6 1 1 75 24 James Hopper Stub Allison (1935-44) 58 42 2 .578 1905 4 1 2 75 12 J.W. -

NCAA Men's Final Four Records (The Final Four)

The Final Four Championship Results ............................... 8 Final Four Game Records.......................... 9 Championship Game Records ............... 12 Semifinal Game Records ........................... 14 Final Four Two-Game Records ............... 17 Final Four Cumulative Records .............. 18 8 CHAMPIONSHIP RESULts Championship Results Year Champion Score Runner-Up Third Place Fourth Place 1939 Oregon 46-33 Ohio St. † Oklahoma † Villanova 1940 Indiana 60-42 Kansas † Duquesne † Southern California 1941 Wisconsin 39-34 Washington St. † Pittsburgh † Arkansas 1942 Stanford 53-38 Dartmouth † Colorado † Kentucky 1943 Wyoming 46-34 Georgetown † Texas † DePaul 1944 Utah 42-40 + Dartmouth † Iowa St. † Ohio St. 1945 Oklahoma St. 49-45 New York U. † Arkansas † Ohio St. 1946 Oklahoma St. 43-40 North Carolina Ohio St. California 1947 Holy Cross 58-47 Oklahoma Texas CCNY 1948 Kentucky 58-42 Baylor Holy Cross Kansas St. 1949 Kentucky 46-36 Oklahoma St. Illinois Oregon St. 1950 CCNY 71-68 Bradley North Carolina St. Baylor 1951 Kentucky 68-58 Kansas St. Illinois Oklahoma St. 1952 Kansas 80-63 St. John’s (NY) Illinois Santa Clara 1953 Indiana 69-68 Kansas Washington LSU 1954 La Salle 92-76 Bradley Penn St. Southern California 1955 San Francisco 77-63 La Salle Colorado Iowa 1956 San Francisco 83-71 Iowa Temple SMU 1957 North Carolina 54-53 ‡ Kansas San Francisco Michigan St. hotos 1958 Kentucky 84-72 Seattle Temple Kansas St. P AA 1959 California 71-70 West Virginia Cincinnati Louisville C N 1960 Ohio St. 75-55 California Cincinnati New York U. 1961 Cincinnati 70-65 + Ohio St. * St. Joseph’s Utah cKee/ 1962 Cincinnati 71-59 Ohio St. Wake Forest UCLA M 1963 Loyola (IL) 60-58 + Cincinnati Duke Oregon St.