Private Nuisance Law: a Window on Substantive Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anomalies in Intentional Tort Law

Tennessee Journal of Law and Policy Volume 1 Issue 2 Winter 2005 Article 3 January 2005 Anomalies in Intentional Tort Law Alan Calnan Southwestern University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/tjlp Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Calnan, Alan (2005) "Anomalies in Intentional Tort Law," Tennessee Journal of Law and Policy: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/tjlp/vol1/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Tennessee Journal of Law and Policy by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/tjlp. Anomalies in Intentional Tort Law Cover Page Footnote Paul E. Treusch Professor of Law, Southwestern University School of Law. I would like to thank Southwestern University School of Law for supporting this project with a sabbatical leave and a summer research grant. This article is available in Tennessee Journal of Law and Policy: https://trace.tennessee.edu/tjlp/vol1/iss2/3 ANOMALIES IN INTENTIONAL TORT LAW Anomalies in Intentional Tort Law Alan Calnan* Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................. 187 H. The Theoretical Paradigm of Tort Law ............................ 191 A. The Form and Function of the FaultMatrix B. Seeing Beyond the Matrix III. Unintentional and Unrecognized Intentional Torts .................. 207 A. UnintentionalIntentional Torts 1. Transferred Intent 2. Mistake B. UnrecognizedIntentional Torts 1. The Scienter Conundrum 2. The Restatement (Third)"Solution" IV. -

Tort Law Notes

https://www.uninote.co.uk/vendor/kings-llb-student/ All rights reserved to the author. Tort Law Notes Part 1 out of 2 [127 pages] Contents: Intentional Interferences with the Person + Defences Occupiers’ Liability Nuisance + The Tort in Rylands v Fletcher Remedies Vicarious Liability 1 https://www.uninote.co.uk/vendor/kings-llb-student/ All rights reserved to the author. Intentional Interferences with the Person Who can sue whom, in what tort, for what damage and are there any defences? Causes of Action Trespass to the person is an intentional tort = the conduct must be deliberate. It is the act and not the injury that has to be intentional, D does not need to intend to commit a tort or cause harm. Trespass is actionable without proof of damage. Letang v Cooper [1965] QB 232 Patch of land/grass used as car park for a hotel. Claimant sunbathing on that patch, car ran over her. Suffered severe injuries to her legs, she sued. It mattered whether she was bringing her claim in the tort of battery and in the tort of negligence because of the limitation period. This no longer applies because of new statute (private law 6 years, personal injury 3 years). Lord Denning: “We divide the causes of action now according as the defendant did the injury intentionally or unintentionally.” Intentionally = trespass to the person Unintentionally = negligence ASSAULT An assault is an act which causes another person to apprehend the infliction of immediate, unlawful, force on his person. Assault protects the right not to be put in fear of unlawful invasion of our integrity. -

Toxic Trespass: Lead Us Not Into Litigation

toxic trespass: lead us not into litigation 44 by Steven N. Geise and Hollis R. Peterson Since the chemical revolution began to unfold in the 1950s, people have ingested hundreds of toxic substances—knowingly or not. Our bodies carry chemicals found in the products and processes we use or to which we are exposed. Many toxins take up residence in body fat, where they may remain for decades; others are absorbed into the body and quickly metabolized and excreted. Winds and water currents can carry persistent chemicals thousands of miles until they find a home in our blood- streams. Just by living in an industrialized society, we all carry a sampling of the chem- ical cocktail created by our surroundings. As modern science advances, biomonitor- ing data is able to detect the presence of specific toxins. But science cannot always inform us about how the chemi- cals were introduced, how long they have been there, or whether they pose a legiti- mate health risk. If not for recent develop- ments in detection, we might never know that our bodies harbor such chemicals. 55 Nevertheless, creative litigants are forcing courts to deal with (“CELDF”) has proposed a strict-liability model ordinance to a new wave of toxic tort claims seeking to make chemicals local legislators that recognizes “that it is an inviolate, funda- in a person’s bloodstream an actionable offense. This cause mental, and inalienable right of each person … to be free from of action is known as “toxic trespass.” Courts must decide involuntary invasions of their bodies by corporate chemicals.” whether the mere presence of chemicals in an individual Corporate Chemical Trespass Ordinance, http://www.celdf.org/ gives rise to civil liability when the individual has no diag- Ordinances/CorporateChemicalTrespassOrdinance/tabid/257/ nosed injury and the causal link between the exposure and Default.aspx (web sites last visited February 6, 2009). -

FTCA Handbook Is a Revision of the Material Originally Published in July 1979 and Updated Periodically Since

JACS-Z 1 November 1999 MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMS JUDGE ADVOCATES/CLAIMS ATTORNEYS SUBJECT: Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) Handbook 1. This edition of the FTCA Handbook is a revision of the material originally published in July 1979 and updated periodically since. The previous edition was last updated in September 1998. This edition contains significant cases through September 1999 pertaining to the filing and processing of administrative claims under the FTCA (Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2671-2680) and related claims statutes. 2. This Handbook provides case citations covering a myriad of issues. The citations are organized in a topical manner, paralleling the steps an attorney should take in analyzing a claim. Older citations have not been removed. Shepardizing is essential. 3. If any errors are noted, including the omission of relevant cases, please use the error sheet at the end of the Handbook to bring this to our attention. Users needing further information or clarification of this material should contact their Area Action Officer or Mr. Joseph H. Rouse, Deputy Chief, Tort Claims Division, DSN: 923-7009, extension 212; or commercial: (301) 677-7009, extension 212. JOHN H. NOLAN III Colonel, JA Commanding TABLE OF CONTENTS I. REQUIREMENTS FOR ADMINISTRATIVE FILING A. Why is There a Requirement? 1. Effective Date of Requirement............................ 1 2. Administrative Filing Requirement Jurisdictional......... 1 3. Waiver of Administrative Filing Requirement.............. 1 4. Purposes of Requirement.................................. 2 5. Administrative Filing Location........................... 2 6. Not Necessary for Compulsory Counterclaim................ 2 7. Not Necessary for Third Party Practice................... 2 B. What Must be Filed? 1. Written Demand for Sum Certain.......................... -

Sniadach, the Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B

Boston College Law Review Volume 14 Article 2 Issue 3 Number 3 2-1-1973 Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B. McDonnell Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Julian B. McDonnell, Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism?, 14 B.C.L. Rev. 437 (1973), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol14/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SNIADACH, THE REPLEVIN CASES AND SELF-HELP REPOSSESSION-DUE PROCESS TOKENISM? JULIAN B. MCDONNELL* Last term, a divided United States Supreme Court invalidated the replevin statutes of Pennsylvania and Florida. In Fuentes v. Shevinl and Parham v. Cortese' (the Replevin Cases), the Court held these statutes unconstitutional insofar as they authorized repossession of collateral through state officials before the debtor was notified of the attempted repossession and accorded an opportunity to be heard on the merits of the creditor's claim. The Replevin Cases involved typical consumer purchases of household pods,' and accordingly raised new questions about the basic relationship between secured creditors and consumer debtors—a relationship upon which our consumer credit economy is based. Creditors have traditionally regarded the right to immediate repossession of collateral after determining the debtor to be in default as the essence of personal property security arrange- ments,' and their standard-form security agreements typically spell out this right. -

Imposed in Intentional Torts Suits Defendant Are at Fault

Using Comparative Fault to Replace the All-or-Nothing Lottery Imposed in Intentional Torts Suits in Which Both Plaintiff and Defendant Are at Fault Gail D. Hollister* I. INTRODUCTION .......................................... 122 II. REASONS FOR USING COMPARATIVE FAULT IN INTENTIONAL TORT CASES ............................................ 127 III. JUSTIFICATIONS OFFERED TO SUPPORT THE BLANKET PROHI- BITION ON THE USE OF COMPARATIVE FAULT IN INTEN- TIONAL TORT CASES ..................................... 132 A. Plaintiff's Fault Must Be Ignored to Circumvent the Harsh Results Imposed by Contributory Negli- gence ......................................... 132 B. Comparative Negligence Statutes Prohibit the Use of Comparative Fault in Intentional Tort Cases.. 134 C. Intent and Negligence Are Different in Kind and Thus Cannot Be Compared ..................... 135 1. Do Negligence and Intent Differ in Kind? .. 136 2. Do Differences in Kind Mandate Different R esults? .... 141 D. Plaintiff Is Entitled to Full Compensation....... 143 E. Plaintiff Has No Duty to Act Reasonably to Avoid H arm ......................................... 143 F. Plaintiff's Fault Cannot Be a Proximate Cause of H er Injury .................................... 144 G. The Need to Punish Defendant Precludes the Use of Comparative Fault .......................... 145 * Associate Professor of Law, Fordham University. B.S., University of Wisconsin, 1967; J.D., Fordham University School of Law, 1970. The author would like to thank Professors Helen Hadjiyannakis Bender, Robert M. Byrn, and Ludwik A. Teclaff for their helpful comments on earlier drafts. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW [Vol. 46:121 H. The Need to Deter Substandard Conduct Makes Comparative Fault Undesirable................. 146 L Victim Compensation Militates Against the Use of Comparative Fault ............................ 149 IV. WHEN COMPARATIVE FAULT SHOULD BE USED IN INTEN- TIONAL TORT CASES ................................ -

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1. Introduction 2. The Basis of Tort Law 3. Intentional Torts 4. Negligence 5. Cyber Torts: Defamation Online 6. Strict Liability 7. Product Liability 8. Defenses to Product Liability 9. Tort Law and the Paralegal Chapter Objectives After completing this chapter, you will know: • What a tort is, the purpose of tort law, and the three basic categories of torts. • The four elements of negligence. • What is meant by strict liability and under what circumstances strict liability is applied. • The meaning of strict product liability and the underlying policy for imposing strict product liability. • What defenses can be raised in product liability actions. Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline I. INTRODUCTION A. Torts are wrongful actions. B. The word tort is French for “wrong.” II. THE BASIS OF TORT LAW A. Two notions serve as the basis of all torts. i. Wrongs ii. Compensation B. In a tort action, one person or group brings a personal-injury suit against another person or group to obtain compensation or other relief for the harm suffered. C. Tort suits involve “private” wrongs, distinguishable from criminal actions that involve “public” wrongs. D. The purpose of tort law is to provide remedies for the invasion of various interests. E. There are three broad classifications of torts. i. Intentional Torts ii. Negligence iii. Strict Liability F. The classification of a particular tort depends largely on how the tort occurs (intentionally or unintentionally) and the surrounding circumstances. Intentional Intentions An intentional tort requires only that the tortfeasor, the actor/wrongdoer, intended, or knew with substantial certainty, that certain consequences would result from the action. -

Torts Mnemonics

TORTS MNEMONICS 1) Torts are done IN SIN: I – INTENTIONAL harm to a person (e.g., assault, battery, false imprisonment, or the intentional infliction of emotional harm) N – NEGLIGENT conduct causing personal injury, wrongful death, or prop damage S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL harm to property (e.g., trespass, conversion, or tortious interference with a contract) N – NUISANCE 2) Tortious conduct makes you want to SING: S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL conduct N – NEGLIGENT conduct G – GROSS negligence a/k/a reckless conduct 3) A D’s FIT conduct is unreasonable/negligent when P was within the foreseeable zone of danger: F – FAILURE to take reasonable precautions in light of foreseeable risks I – INADVERTENCE T – THOUGHTLESSNESS 4) To establish a negligence claim, P must mix the right DIP: D – DUTY to exercise reasonable care was owed by the D to the injured P and the D breached this duty (for a negligence claim the duty is always to conform to the legal standard of reasonable conduct in light of the apparent risks) I – Physical INJURY to the P or his property (damages) P – P’s injuries were PROXIMATELY caused by the D’s breach of duty 5) A parent is liable only for the torts of a SICK child: S – in an employment relationship where a child commits a tort, while acting as a SERVANT or agent of the parent I – where the parent entrusts or knowingly leaves in the child’s possession an INSTRUMENTALITY that, in light of the child’s age, intelligence, disposition and prior experience, creates an unreasonable risk of harm to -

Contra Costa Superior Court Martinez, California Department: 21 Hearing Date: 01/30/19

CONTRA COSTA SUPERIOR COURT MARTINEZ, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT: 21 HEARING DATE: 01/30/19 1. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON TRIAL RE-SETTING * TENTATIVE RULING: * Parties to appear. CourtCall is acceptable if there is no argument on line 2. 2. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON DEMURRER TO COMPLAINT FILED BY BAILEY T. LEE, M.D. * TENTATIVE RULING: * The demurrer of defendant Bailey Lee, M.D., to plaintiffs’ complaint is overruled. Defendant shall file and serve his Answer on or before February 13, 2019. Plaintiffs filed this medical malpractice case on September 6, 2016 against defendant Contra Costa County, several physicians, and Does 1-100. Plaintiffs contend they discovered possible liability on the part of Dr. Lee several years after they suit, based upon conversations with an expert consultant. Shortly thereafter, they filed a Doe amendment on September 25, 2018, naming Dr. Lee as Doe 1. Dr. Lee now demurs to the complaint. He argues that the complaint contains no charging allegations against him and that it is uncertain. (CCP § 403.10 (e), (f).) A party who is ignorant of the name of a defendant or the basis for a defendant’s liability may name that defendant by a fictitious name and amend to state the defendant’s true name when the facts are discovered. (CCP § 474; see Breceda v. Gamsby (1968) 267 Cal.App.2d 167, 174.) If section 474 is properly used, no amendment of the complaint is necessary other than the Doe amendment itself. -

I. A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approac

Torts, Sharkey Fall 2006, Dave Fillingame I. INTRODUCTION A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approach B. Holmes: Two theories of common-law liability: 1. Criminalist (Negligence) 2. “A man acts at his own peril” (strict liability) 3. Judge People by an Objective not a Subjective Standard of Care C. Judge v. Jury in Torts II. INTENTIONAL TORTS A. Elements B. Physical Harms 1. Battery a. Eggshell Skull Rule (Vosburg v. Putney) b. Intent to Act v. Intent to Harm c. “Substantial Certainty” Test (Garratt v. Dailey) d. “Playing Piano” (White v. University of Idaho) e. “Transferred” Intent 2. Defenses to Battery: Consent a. Consent b. Consent: Implied License c. Consent to Illegal Acts 3. Defenses to Battery: Insanity 4. Defenses to Battery: Self-Defense and Defense of Others a. Can be used as a defense when innocent bystanders harmed b. Can be used in defense of third-parties c. Must be proportional force 5. Defenses to Battery: Necessity C. Trespass to Land 1. No Damage is Required, Unauthorized Entry on Land is Enough a. An unfounded claim of right does not make a willful entry innocent. b. Quarum Clausum Fregit 2. Use of Deadly Force in Protection of Property a. Posner: We Must Create Incentives to Protect Tulips and Peacocks. b. Use Reasonable Force: Katko v. Briney (Iowa 1971) 3. Defense of Privilege a. Privilege of Necessity b. “General Average Contribution” c. Conditional (Incomplete) Privilege Vincent v. Lake Erie (Minn. 1910) d. The privilege exists only so long as the necessity does. -

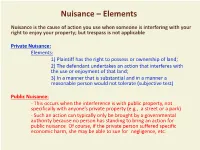

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

Contra Costa Superior Court Martinez, California Department: 33 Hearing Date: 10/11/18

CONTRA COSTA SUPERIOR COURT MARTINEZ, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT: 33 HEARING DATE: 10/11/18 1. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC12-00284 CASE NAME: CERF VS. CHEROKEE SIMEON FURTHER CASE MANAGEMENT CONFERENCE * TENTATIVE RULING: * The Case Management Conference is continued by the Court to October 25, 2018, at 9:00 a.m., in Department 33. 2. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC12-00284 CASE NAME: CERF VS. CHEROKEE SIMEON HEARING ON MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT OR SUMMARY ADJUDICATION FILED BY CHEROKEE SIMEON VENTURE I, LLC, et al. * TENTATIVE RULING: * The hearing on this motion is continued by the Court to October 25, 2018, at 9:00 a.m., in Department 33. The Court will issue a substantive tentative ruling on October 24. 3. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC15-01803 CASE NAME: SANCHEZ VS. WINCO HEARING ON MOTION TO HAVE REQUESTS FOR ADMISSIONS DEEMED ADMITTED FILED BY WINCO FOODS, LLC * TENTATIVE RULING: * Granted. No opposition. Sanctions ordered as requested in the amount of $515 to be paid by November 1, 2018. 4. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC15-01803 CASE NAME: SANCHEZ VS. WINCO HEARING ON MOTION FOR ORDER COMPELLING RESPONSES TO FORM INTERROGS. FILED BY WINCO FOODS, LLC * TENTATIVE RULING: * Granted. No opposition. Verified responses to be served without objection by November 1, 2018. Sanctions ordered as requested in the amount of $372.50 to be paid by that same date. - 1 - CONTRA COSTA SUPERIOR COURT MARTINEZ, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT: 33 HEARING DATE: 10/11/18 5. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01133 CASE NAME: DIRECT CAPITAL VS. SHORTZ HEARING ON MOTION FOR ASSIGNMENT OF RIGHTS, etc.