Sussex EUS – Seaford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission in the Deanery 2011

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !Lewes and Seaford Deanery Synod! MISSION IN THE DEANERY 2011 - 2014 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mission Activity reported to Deanery Synod ! during the Period 2011 - 2014! ! As part of the Pastoral Strategy, Deanery Synod is committed always to include an item relevant to our mission of growing the church. The following items have been included in !synods as part of this commitment during the triennium which closes in May 2014.! ! Church Schools in the Deanery, Diocese and Nation. (Rodmell, September 2011) 3! Aspects of Prayer in the Deanery (South Malling: November, 2011) !! ! 5! Developing a Mission Action Plan (East Blatchington: February 2012)!! 6! Mission in a large Rural benefice ((Arlington, Wilmington, Berwick, ! and Selmeston with Alciston : 8 May, 2012)!!!!!! 6! Mission in Peacehaven, Telscombe Cliff and Piddinghoe (Peacehaven Sept. 2012) 7! Mission in the Benefice of Sutton with Seaford!(Seaford, November 2012)!! 8! The Street Pastor Scheme in Seaford!!!!!!! 8! Mission in the parish of Barcombe! !!!!!! 8! Chaplaincy in the Deanery - A flavour!!!!!!! 9! Mission Developments in three Lewes Parishes!!!!! 9! Cursillo (Arlington etc!!!!!!!! 10! Training Readers!!!!!!!!!! 10! Mission to Young People!!!!!!!!! 11! !The Parish Giving Scheme!!!!!!!!! 12! ! ! !Other items. Separate Booklets are:! Healing Ministry in the Churches of the Lewes and Seaford Deanery (November 2012)! !Lewes and Seaford Pastoral Strategy Revised November 2014 ! ! Also: ! Lewes and Seaford Deanery Synod: 2011 The Four Hundredth Anniversary of the King James Bible: Celebrations that have taken place in the Lewes and Seaford Deanery !(February 2012)! Lewes and Seaford Churches Celebrations in 2012: Jubilee, Olympics and Book of !Common Prayer (May 2012)! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "2 of "12 !Church Schools in the Deanery, and Diocese. -

SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL (INCLUDING STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT) Submission Version

SEAFORD NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2017-2030 Seaford Town Council SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL (INCLUDING STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT) Submission Version May 2019 Seaford Neighbourhood Plan Sustainability Appraisal February 2019 Contents NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 1 1.INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 11 WHAT IS A SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL (INCLUDING STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT)? ................................................................................................................................................ 13 WHAT IS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT? .................................................................................... 14 HOW TO COMMENT ON THE SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL ............................................................. 15 STRUCTURE OF THE SA ............................................................................................................. 15 COMPLIANCE WITH ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF PLANS AND PROGRAMMES REGULATIONS . 16 HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT...................................................................................... 16 2. SEAFORD NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN .................................................................................... 18 NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING AREA ........................................................................................... 18 NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN VISION -

Seaford Neighbourhood Plan 2017 – 2030 Pre-Submission Version for Regulation 14 Consultation

Seaford Neighbourhood Plan Version for Regulation 14 Consultation Seaford Neighbourhood Plan 2017 – 2030 Pre-Submission Version for Regulation 14 Consultation Published by Seaford Town Council for Pre-Submission Consultation under the Neighbourhood Planning (General) Regulations 2012 and in accordance with EU Directive 2001/42 0 Seaford Neighbourhood Plan Version for Regulation 14 Consultation Contents Note this report is colour coded for ease of reference: Blue is introductory and contextual material; Green is the vision, objectives and planning policies of the Neighbourhood Plan; and Orange is the other aspirations and delivery proposals and the appendices Non-Technical Summary p3 1.0 How to Read and Use the Seaford Neighbourhood Plan p10 2.0 Neighbourhood Planning: Legislative and Planning Policy Context p12 - National Planning Policy Framework p12 - The National Park Purposes p13 - Local Planning Context p13 - The Link Between Development and Infrastructure p14 - Sustainability Appraisal and Strategic Environmental Assessment p14 - The Plan Preparation Process p15 - The Examination Process p15 - The Approval Process p16 3.0 Community Consultation p17 4.0 The Parish of Seaford p19 5.0 Vision & Objectives p21 6.0 Policies & Proposals p22 - Introduction p22 - Environment and Countryside p23 Landscape, Seascape and Townscape p23 Design p24 Heritage Assets p26 Seaford Seafront p30 Recreation p31 Local Green Spaces p32 Allotments p33 -Economy and Facilities p34 Infrastructure p34 Health p34 Town Centre p34 Business Space p35 Visitor Accommodation -

Notice of Election

NOTICE OF ELECTION ELECTION OF TOWN AND PARISH COUNCILLORS FOR ALL TOWN AND PARISH COUNCILS WITHIN THE DISTRICT OF LEWES 1 Elections are to be held of Town and Parish Councillors for each of the Town and Parish Councils within the District of Lewes. The number of Councillors to be elected in each Town or Parish is as follows: BARCOMBE ELEVEN - Peacehaven North Ward FIVE CHAILEY ELEVEN - Peacehaven West Ward SIX DITCHLING ELEVEN PIDDINGHOE FIVE EAST CHILTINGTON SEVEN PLUMPTON NINE FALMER FIVE RINGMER THIRTEEN FIRLE FIVE RODMELL SEVEN GLYNDE AND BEDDINGHAM SEAFORD - Parish of Beddingham FOUR - Seaford Bay Ward ONE - Parish of Glynde THREE - Seaford Bishopstone Ward TWO HAMSEY SEVEN - Seaford Central Ward TWO KINGSTON SEVEN - Seaford East Blatchington Ward ONE LEWES - Seaford East Ward FOUR - Lewes Bridge Ward FIVE - Seaford Esplanade Ward TWO - Lewes Castle Ward FOUR - Seaford North Ward FOUR - Lewes Central Ward ONE - Seaford South Ward THREE - Lewes Priory Ward EIGHT - Seaford Sutton Ward ONE NEWHAVEN SOUTH HEIGHTON SEVEN - Newhaven Central Ward TWO TELSCOMBE - Newhaven Denton Ward FIVE - East Saltdean Ward FIVE - Newhaven North Ward THREE - Telscombe Cliffs Ward EIGHT - Newhaven South Ward EIGHT WESTMESTON SEVEN NEWICK ELEVEN WIVELSFIELD NINE PEACEHAVEN - Peacehaven Central Ward ONE - Peacehaven East Ward FIVE 2 Nomination papers must be delivered to the Returning Officer at the Electoral Services office of Lewes District Council, Southover House, Southover Road, Lewes, East Sussex BN7 1AB between the hours of 9am to 4pm Monday to Friday after the date of this notice and not later than 4pm on Wednesday, 3 April 2019. 3 Forms of nomination paper may be obtained at the place and within the time set out in 2 above. -

Cross Keys Junel 2020 for Magazine

Life under Lockdown The Rector’s reflections I have said Mass inside the empty church just I know have stopped saying the Mass three times since lockdown began and all altogether feeling that they should fast with three times broke my heart. I have said Mass a their congregation and I too have wrestled with number of times in my study which has been what is the right thing to do. However, the equally, though differently, uncomfortable. sacramental theology that I have grown up Both situations have given me a fresh insight with and still hold fast to means that the into the sacrament, the Christian community, breaking of bread is never only for the people and the presence of Christ but the physical who are gathered, but for the whole world, for absence of the people (all of you) is an ache those who are absent but in need of prayer, for that is practically unbearable. Some priests the souls of the dead, and for the life of the church. The Magazine of the Parish of St Peter, East Blatchington June/July 2020 2 . Even more so, at each and every Mass earth these churches is as yet unknown and quite participates in heaven because Jesus Christ daunting. We are so aware that your physical being present in the world through the safety needs to run alongside your spiritual Eucharist, is of cosmic as much as human health and finding the right balance between importance. His presence in the broken bread these is going to be tough. and wine, assumes his presence in your heart and your presence with him as members of Lastly, I’d like to say something about grief and the mystical Body of Christ. -

Of Place-Names in Sussex

PREPARATORY TO A DICTIONARY OF SUSSEX PLACE-NAMES Richard Coates University of the West of England, Bristol © 2017 First tranche: place-names in A, E, I, O and U 1 Foreword It is now almost 90 years since the publication of Allen Mawer and Frank Stenton’s standard county survey The place-names of Sussex (English Place-Name Society [EPNS] vols 6-7, Cambridge University Press, 1929-30). While I was living and working in Sussex, before 2006, it had long been my intention to produce an updated but scaled- down of this major work to serve as one of the EPNS’s “Popular” series of county dictionaries. Many things have intervened to delay the fulfilment of this aspiration, but it struck me that I could advance the project a little, put a few new ideas into the public domain, and possibly apply a spur to myself, by publishing from time to time an online “fascicle” consisting of analyses of selected major or important names beginning with a particular letter. Here are the first five, dealing with the letters A, E, I, O and U. Readers are invited to send any comments, including suggestions for inclusion or improvement, to me at [email protected]. With that end in mind, the present work consists of an index in electronic form of the names covered by Mawer and Stenton, kindly supplied many years ago, before I was acquainted with the joys of scanning, by Dr Paul Cavill. For some of these names, those which Percy Reaney called “names of primary historical or etymological interest” (interpreted subjectively), I have constructed a dictionary entry consisting of evidence and commentary in the usual way, plus a National Grid reference and a reference to the relevant page-number in Mawer and Stenton (e.g. -

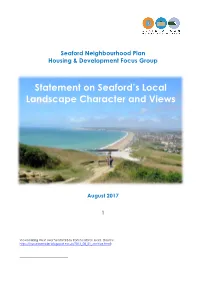

Landscape Character Views

Seaford Neighbourhood Plan Housing & Development Focus Group Statement on Seaford’s Local Landscape Character and Views August 2017 1 View looking West over Seaford Bay from Seaford Head. (Source: https://sussexrambler.blogspot.co.uk/2013_08_01_archive.html) Contents Page 1. Introduction 1.1 Purpose of this Report 4 1.2 Definition of Landscape Character 4 1.3 Methodology for Development of Local Landscape Character 5 2. Existing Landscape Character Assessments 2.1 Historic Landscape Character 5 2.2 Landscape Types 6 2.2.1 Open Downland 7 2.2.2 Shoreline 9 2.3 Townscape Character 15 3. Key Views 3.1 Existing Policy Framework 16 3.2 Landscape Character and Key Views Policy 17 3.3 South Downs National Park View Characterisation Analysis Report 17 3.3.1 Representative Views 18 3.3.2 Landmarks 25 3.3.3 Special Qualities, Threats and Management Guidance 26 3.4 Significant Public Views - Views Identified in Conservation Area Appraisals 28 3.4.1 Seaford Town Centre 29 3.4.2 Bishopstone 32 3.4.3 East Blatchington 35 3.4.4 Chyngton Lane 37 3.5 Significant Public Views – Views Selected by Residents 39 3.5.1 Criteria for Selecting Views 39 Map 40 3.5.2 Significant Public Views towards, from and within the National Park 42 3.5.3 Seascape Views 52 3.5.4 Distinctive Local Views 53 4. Issues, Threats and Mitigation 55 5. References 57 Map showing the Parish boundary and the boundary of the South Downs National Park, which tightly follows the built up area. 61.4% of the Parish is in the SDNP. -

Lewes District Council

Lewes District Council Lewes House High Street Lewes East Sussex BN7 2LX Chairman's Secretary : Lewes (01273) 484112 CHAIR Fax : Lewes (01273) 484146 COUNCILLOR CARLA BUTLER [email protected] CHAIR OF THE COUNCIL’S ENGAGEMENTS 14 May 2008 – 23 July Thursday 15 May 6.50 pm Chair to attend the annual meeting of Lewes Town Council and the ceremony of Mayor Making at the Town Hall, Lewes. Saturday 17 May 11.00 am Chair to attend the launch of the Heritage Lottery Funded Leighside Pond project in Lewes the culmination of hard work by the Railway Land Junior Management Board. Wednesday 21 May 11.45 am Chair to attend the official opening of the Newhaven Enterprise Centre, Denton Island, Newhaven. Friday 6 June 1.20 pm Chair to take part in the visit of HRH the Duchess of Gloucester GCVO to Chailey School to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the opening of the school and a Citizenship ceremony. 6.00 pm Chair to attend a reception to celebrate the achievements of the Friends of East Sussex Record Office over the past 25 years at Herstmonceux Castle. 7.00 pm Vice Chair to represent the Chair at a Mayoral Reception hosted by the Mayor of Peacehaven at the Community House, Meridian Centre, Peacehaven. Sunday 8 June 3.30 pm Chair to attend a Civic service at St Peter's Church, East Blatchington, Seaford organised by Churches in Seaford. Page 1 of 4 Tuesday 10 June 10.00 am Chair to accompany an officer of the Council on a visit to various businesses in Peacehaven to make them aware of the small business rates relief available to small businesses. -

East Sussex Record Office Report of the County Archivist April 2012 to March 2014

eastsussex.gov.uk East Sussex Record Office Report of the County Archivist April 2012 to March 2014 2014/15: 458 Introduction The period covered by this annual report – the financial years 2012-2014 – has probably been the most momentous in ESRO’s history as it saw the completion of the project to build and open The Keep. It marked the culmination of seven years’ work by the project partners, East Sussex County Council, Brighton & Hove City Council and The University of Sussex to re-house their archives and other historical resources in a state-of-the-art building, both to ensure their permanent preservation and to increase and broaden access to this unique and irreplaceable material. Practical completion was achieved on 17 June 2013 when the building was handed over by the contractors, Kier. We immediately began to move ESRO material into The Keep, which was not as easy as it sounds – the work required to prepare the archives for transfer and then to move them is described elsewhere in this report. Staff worked long, hard hours preparing and supervising the ESRO removals. It was a remarkable feat and as a result all ESRO’s archives have been listed to at least collection level, packaged and shelved appropriately in a single building and can be tracked around it via the inventory management (barcoding) system. The service we now offer is not merely ESRO in a new building, but has been transformed into a fully integrated partnership, working not just to better but rather transcend what we previously provided. Behind the scenes each partner continues to maintain their individual collections in their separate databases but from the user’s point of view the service is seamless: the online catalogue and ordering system combine information from the three databases and presents them as a single resource on The Keep’s new website, www.thekeep. -

Planning Feasibility Study

Prepared in accordance with the Royal Town Planning Institute Code of Conduct PLANNING FEASIBILITY STUDY Blatchington House, Firle Road, Seaford, East Sussex, BN25 2HH Alex Bateman BA (Hons) MSc MRTPI August 2014 Blatchington House, Firle Road, Seaford, East Sussex, BN25 2HH Planning Feasibility Study Contents Page 1.0 Introduction 2 2.0 Site Description 3 3.0 Planning Policy 8 4.0 Pre-Application Discussions 16 5.0 Material Planning Considerations 19 6.0 Summary and Recommendations 21 Appendix Location Plan A Lewes District Council NPPF Compliant Report B Pre-Application Documentation C Pre-Application Response from Council D Page 1 Blatchington House, Firle Road, Seaford, East Sussex, BN25 2HH Planning Feasibility Study Introduction 1.1 This planning feasibility study is for the building and land at Blatchington House, Firle Road, Seaford, East Sussex, BN25 2HH (see Appendix A). 1.2 Stiles Harold Williams Planning Consultancy Department has been instructed to assess the likelihood of obtaining alternative planning permissions in relation to the land and buildings. 1.3 The site is located within the Lewes District Council whom will be the determining authority for any future planning applications. 1.4 To fulfil the Planning Consultancy Department’s brief, SHW have undertaken an appraisal of extant and emerging local and national planning policy, submission of the pre-application documents and attending meeting with Lewes District Council to determine the likelihood of obtaining planning permission for alternative uses. Page 2 Blatchington House, Firle Road, Seaford, East Sussex, BN25 2HH Planning Feasibility Study 2.0 Site Description 2.1 The site is currently occupied by a large single dwelling used as a nursing care home (Use Class C2) and its grounds. -

Seaward Sussex - the South Downs from End to End

Seaward Sussex - The South Downs from End to End Edric Holmes The Project Gutenberg EBook of Seaward Sussex, by Edric Holmes This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Seaward Sussex The South Downs from End to End Author: Edric Holmes Release Date: June 11, 2004 [EBook #12585] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SEAWARD SUSSEX *** Produced by Dave Morgan, Beth Trapaga and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. [Illustration: HURSTMONCEUX.] SEAWARD SUSSEX THE SOUTH DOWNS FROM END TO END BY EDRIC HOLMES ONE HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARY M. VIGERS MAPS AND PLANS BY THE AUTHOR Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. LONDON: ROBERT SCOTT ROXBURGHE HOUSE PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. MCMXX "How shall I tell you of the freedom of the Downs-- You who love the dusty life and durance of great towns, And think the only flowers that please embroider ladies' gowns-- How shall I tell you ..." EDWARD WYNDHAM TEMPEST. Every writer on Sussex must be indebted more or less to the researches and to the archaeological knowledge of the first serious historian of the county, M.A. Lower. I tender to his memory and also to his successors, who have been at one time or another the good companions of the way, my grateful thanks for what they have taught me of things beautiful and precious in Seaward Sussex. -

Seaford Historic Character Assessment Report Pages 1 to 12

Seaford Historic Character Assessment Report March 2005 Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS) Roland B Harris Seaford Historic Character Assessment Report March 2005 Roland B Harris Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS) in association with Lewes District Council Sussex EUS – Seaford The Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (Sussex EUS) is a study of 41 towns undertaken between 2004 and 2007 by an independent consultant (Dr Roland B Harris, BA DPhil MIFA) for East Sussex County Council (ESCC), West Sussex County Council (WSCC), and Brighton and Hove City Council; and was funded by English Heritage. Guidance and web-sites derived from the historic town studies will be, or have been, developed by the local authorities. All photographs and illustrations are by the author. First edition: March 2005. Copyright © East Sussex County Council, West Sussex County Council, and Brighton and Hove City Council 2005 Contact: For West Sussex towns: 01243 642119 (West Sussex County Council) For East Sussex towns and Brighton & Hove: 01273 481608 (East Sussex County Council) The Ordnance Survey map data included within this report is provided by East Sussex County Council under licence from the Ordnance Survey. Licence LA 076600 2004. The geological map data included within this report is reproduced from the British Geological Map data at the original scale of 1:50,000. Licence 2003/070 British Geological Survey. NERC. All rights reserved. The views in this technical report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of English Heritage, East Sussex County Council, West Sussex County Council, Brighton & Hove City Council, or the authorities participating in the Character of West Sussex Partnership Programme.