Of Place-Names in Sussex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admission Arrangements for Rye College 2020 – 2021

Admission Arrangements for Rye College 2020 – 2021 Rye College is a mixed ability secondary academy in the heart of the Rye community providing places for boys and girls between the ages of 11 and 16. Rye College has high expectations and is ambitious for its students. The rigorous focus on the child as a unique individual ensures that the lessons they receive are personalised and allow them to be actively engaged in their learning. The students at Rye College understand that hard work, self-motivation, inquisition, ambition and resilience are essential in order for them to achieve the best qualifications possible, equipping them for a rapidly changing, highly competitive and exciting world. Rye College is an academy within the Aquinas Church of England Education Trust (the Trust), which is the admission authority for Rye College. These admission arrangements are determined by the admission authority in accordance with the Supplemental Funding Agreement and the School Admissions Code and the School Admissions Appeals Code. General Principles The Trust is its own admissions authority and determines a Published Admissions Number (PAN) for each of its schools. PAN is the number of school places in the relevant age group (or the year group associated with the normal point of entry to a school) i.e. Year 7 for Rye College. The Trust adheres to the School Admissions Code when consulting and determining its admission arrangements giving priority to a child looked after or previously looked after, and does not discriminate against applicants with special needs or disabilities. The Trust will consult on any proposed changes to the PAN following the consultation procedures prescribed by East Sussex County Council (ESCC). -

Habitats Regulations Assessment June 2021

Horsham Local Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment Horsham District Council July 2021 Horsham Local Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment Quality information Prepared by Checked by Verified by Approved by Damiano Weitowitz James Riley Max Wade James Riley Consultant Ecologist Technical Director Technical Director Technical Director Isla Hoffmann Heap Senior Ecologist Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 0 13/10/20 Emerging draft JR James Riley Technical to inform plan Director development 1 18/12/20 Updated to JR James Riley Technical assess Director Regulation 19 LP. 2 15/01/2021 Update JR James Riley Technical following client Director comments 3 30/06/21 Further update JR James Riley Technical Director Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name Prepared for: Horsham District Council AECOM Horsham Local Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment Prepared for: Horsham District Council Prepared by: AECOM Limited Midpoint, Alencon Link Basingstoke Hampshire RG21 7PP United Kingdom T: +44(0)1256 310200 aecom.com © 2021 AECOM Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. Prepared for: Horsham District Council AECOM Horsham Local Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................ -

Local Defibrillators Fulking

Local Defibrillators If you are planning a cardiac event then it makes sense (i) to have it in a location that has a defibrillator available, (ii) to have with you a companion who knows exactly where the defibrillator is, and (iii) for that companion to have some idea how to use it. The text, maps, and photos on this webpage are intended to facilitate the first two goals. With regard to the third goal, modern public access defibrillators are designed to be usable without prior instruction (they talk you through the process) but your companion will feel much more confident about saving your life if they have attended one of the many defibrillator and resuscitation courses on offer locally. Contact HART to discover times and locations. Finally, you can encourage your companion to do some relevant reading. Fulking The Fulking defibrillator is in the centre of the village. The red door to the right is the entrance to the green corrugated iron shack that has served as the village hall for the last ninety years. The porch to the left is the entrance to a tiny brick chapel now used as the church bookstore. The defibrillator is in this porch and is accessible 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Edburton The Edburton defibrillator is located at Coles Automotive which is at the end of Browns Meadow, a track that begins roughly opposite to Springs Smoked Salmon. It is kept in their reception area and is thus only accessible during garage opening hours. Poynings: The Forge Garage Poynings has two defibrillators. -

Albourne Parish Neighbourhood Plan

ALBOURNE PARISH COUNCIL Albourne Parish Council Neighbourhood Plan 2014 – 2031 Plan Status - Made – September 2016 Note: This document is available as follows: On the Parish Council website: www.albourneparishcouncil.co.uk Paper copies for inspection at Albourne Village Hall, by prior appointment only, through 01273 833978 or 01273 835382 Paper copies for purchase (£4.00) on request through 01273 833978 or 01273 835382 Page 1 ALBOURNE PARISH COUNCIL NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN – Made Version ALBOURNE PARISH COUNCIL Contents: Page: 1. Introduction and Neighbourhood Plan Area Map 3 2. Background and general policies 5 3. Countryside, landscape and conservation 7 4. Housing 11 5. Economy and Employment 15 6. Transport 17 7. Amenities 19 8. Schedule of evidence 21 9. Maps 22 List of Policies: ALC1: Countryside - Conserving and Enhancing Character ALC2: Countryside - South Downs National Park ALC3: Countryside - Local Gaps and Preventing Coalescence ALH1: Housing - Housing Development ALH2: Housing - Proposed Housing Sites ALE1: Employment ALE2: Tourism Page 2 ALBOURNE PARISH COUNCIL NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN – Made Version ALBOURNE PARISH COUNCIL 1. Introduction and Neighbourhood Plan Area Map: Albourne Parish Council’s Neighbourhood Plan covers the whole Parish area for the period up to 2031. It sets out the development principles and allocation of areas for future building and land use. This SUBMISSION Plan has been produced under the authority of the Localism Act 2011 which empowers parish councils and similar community groups to produce their own development plans. The plans, having been subject to rigorous tests to ensure that they comply with the relevant planning law and guidelines, and subject to the support from a local public referendum, then become the local planning guidance for the parish area. -

Open Space Strategy

Lewes District Open Space Strategy Document Title Open Space Strategy Prepared for Lewes District Council Prepared by TEP - Warrington Document Ref 7449.007 Author Sam Marshall/ Valerie Jennings Date November 2020 Checked Alice Kennedy Approved Francis Hesketh Amendment History Check / Modified Approved Version Date Reason(s) issue Status by by 1.0 05/08/20 VJ AK Full draft Draft Lewes District Open Space Strategy CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 8 3.0 Policy Context ............................................................................................................... 13 4.0 Method .......................................................................................................................... 21 5.0 Identifying Local Needs ................................................................................................. 29 6.0 Auditing Local Provision ................................................................................................ 34 7.0 Setting Standards ......................................................................................................... 50 8.0 Applying Standards ....................................................................................................... 68 9.0 Recommendations and Strategy .................................................................................. -

Election Declaration 2020

LAND DRAINAGE ACT 1991 ROMNEY MARSHES AREA INTERNAL DRAINAGE DISTRICT DECLARATION BY RETURNING OFFICER WHEN NO POLL I, the undersigned, being the Returning Officer for the election of Members of the Drainage Board for the five electoral districts of the above-named Drainage District do hereby declare that as the number of candidates does not exceed the number of persons to be elected the following Candidates are elected as Members of the Drainage Board for the five electoral districts of the Drainage District. Electoral Names of Place of Abode Description Qualification District Candidates Romney Boulden. Rushfield Farmer Retiring Member Marsh Paul Martin Aldington re-elected -do- Clifton-Holt Haguelands Farm Farmer -do- Alan Gordon Burmarsh -do- Cole Sunset Cottage Farmer -do- Dennis James St Mary in the Marsh -do- Furnival Honeychild Manor Farmer -do- Douglas Stephen St Mary in the Marsh -do- Langrish Pickney Bush Farm Farmer -do- Helen Violet Newchurch -do- Langrish Pickney Bush Farm Farmer -do- James Owen Newchurch Walland Apps Boxted Lodge Farmer -do- Marsh Clive Brookland -do- Body Bentley Bungalow Farmer Nominated by Stephen Snargate Owner/Occupier -do- Cooke Broomhill Farm Farmer Retiring Member Frank Arthur Camber re-elected -do- Furnival Dean Court Farmer -do- Charles Brookland -do- Wellsted Millside Farm Farmer -do- Andrew Colin Brenzett -do- Wright Lamb Farm Farmer -do- Simon East Guldeford Denge & Thompson Rosehall Farmer -do- Southbrooks David Snargate -do- Wrout Westbrooke Farmhouse Farmer -do- Michael Edward Lydd Rother -

Planning Statement Stable Field, Wisborough Green February 2021

Planning Statement Stable Field, Wisborough Green February 2021 Project Name: Stable Field, Wisborough Green Location Stable Field, Wisborough Green Client: Norfolk Square Ltd File Reference: P1764 Issue Date Author Checked Notes PL1 13.10.2020 M Warren S Sykes Initial Draft PL2 17.12.2020 S Sykes C Barker Second Draft PL3 07.01.2021 S Sykes C Barker Planning Draft PL4 05.02.2021 S Sykes C Barker Planning Issue Planning Statement – Stable Fields, Wisborough Green 2 Contents Figures ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2. The Site ................................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Planning History .................................................................................................................................... 10 Adjacent Applications .................................................................................................................. 11 4. The Proposal ......................................................................................................................................... 13 5. Policy Overview .................................................................................................................................... -

Hailsham Town Council

HAILSHAM TOWN COUNCIL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN OF a meeting of the HAILSHAM TOWN COUNCIL to be held in the JAMES WEST COMMUNITY CENTRE, BRUNEL DRIVE, HAILSHAM, on Wednesday, 30th January 2019 at 7.30 p.m. 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE: To receive apologies for absence of council members 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST: To receive declarations of disclosable pecuniary interests and any personal and prejudicial interest in respect of items on this agenda. 3. PUBLIC FORUM: A period of not more than 15 minutes will be assigned for the purpose of permitting members of the Public to address the Council or ask questions on matters relevant to responsibilities of the Council, at the discretion of the Chairman. 4. CHAIRMAN’S UPDATE To receive a verbal update from the Chairman of Hailsham Town Council 5. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES To resolve that the Minutes of the Hailsham Town Council Meeting held on 21st November 2018 and the Extraordinary Meeting held on 9th January 2018 may be confirmed as a correct record and signed by the Chairman. 6. COMMITTEE RECOMMENDATIONS TO COUNCIL To consider the following recommendations made by committees, which are outside of their terms of reference or otherwise were resolved as recommendations to full council: 6.1 Strategic Projects Committee 12/12/2018 – Hailsham Cemetery 7. NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN COMMITTEE 7.1 To note the minutes of the Neighbourhood Plan Committee Meeting 13/12/2018 7.2 To approve the Neighbourhood Plan Committee’s delegated authority up to the next Town Council meeting 8. FOOTBALL PROVISION IN HAILSHAM To receive a verbal update regarding a recent meeting held with local football clubs to discuss football provision in Hailsham. -

A27 East of Lewes Improvements PCF Stage 3 – Environmental Assessment Report

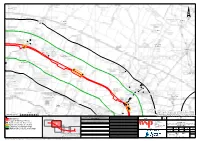

¦ Lower Barn "N Bushy Meadow Lodge Railway View Farm Farm Cottages Lower Mays 4690 Lower Mays Bungalow Mays Farm Middle Farm Pookhill Barn Petland Barn 12378 Sherrington Ludlay Farm Manor Compton Wood Firle Tower Selmeston Green House Beanstalk Charleston Stonery Farm Farm Tilton House 12377 Peaklet Cottage Keepers Sierra Vista Stonery Metres © Crown copyright and databaseFarm rights 2019 Ordnance Survey 100030649. 0 400 You are permitted to use thisCottages data solely to enable you to respond to, or interact with, DO NOT SCALE the organisation that provided you with the data. You are not permitted to copy, Tilton Wood sub-licence, distribute or sell any of this data to third parties in any form. KEY: SAFETY, HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL Drawing Status Suitability Project Title A27 INFORMATON FINAL S0 DESIGN FIX 3 EAST OF LEWES In addition to the hazards/risks normally associated with the types of work Drawing Title FLOOD MITIGATION AREAS detailed on this drawing, note the following significant residual risks WSP House (Reference shall also be made to the design hazard log). 70 Chancery Lane NOISE SENSITIVE RECEPTOR Construction FIGURE 11-1: 2 London NOISE IMPORTANT AREA (NIA) WC2A 1AF NOISE AND VIBRATION CONSTRAINTS PLAN Tel: +44 (0)20 7314 5000 PAGE 2 OF 5 www.wspgroup.co.uk CONSTRUCTION STUDY AREA Maintenance / Cleaning www.pbworld.com Scale Drawn Checked Aproved Authorised OPERATIONAL CALCULATION AREA Copyright © WSP Group (2019) 1:11,000 NF CR GK MS Client Original Size Date Date Date Date Use A3 15/03/19 15/03/19 15/03/19 15/03/19 Drawing Number Project Ref. -

The Winter Games Overall Leaderboard Primary Schools (19/02/2021)

Specsavers ‘Virtual’ Sussex School Games: The Winter Games Overall Leaderboard Primary Schools (19/02/2021) Position School SGO Area Team Points 1 Southwater Junior Academy (Southwater) Central Sussex Dolphins 80 2 Blackthorns Community Primary Academy (Haywards Heath) Mid Sussex Panthers 74 3 St Robert Southwell Catholic Primary School (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 58 4 Farlington School (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 52 5 Greenway Academy (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 39 6 St John's Church of England Primary School (Crowborough) North Wealden Warriors 37 7 Orchards Junior School (Worthing) Southern Sharks 36 8 Elm Grove Primary School (Brighton) Brighton & Hove Hawks 34 9 Chidham Parochial Primary School (Chichester) West Sussex West Wolverines 32 10 Aldrington CofE Primary School (Hove) Brighton & Hove Hawks 30 10 Milton Mount Primary School (Crawley) Crawley Cougars 30 12 Holbrook Primary School (Horsham) Central Sussex Dolphins 28 13 Seymour Primary School (Crawley) Crawley Cougars 24 14 East Preston Junior School (Littlehampton) Southern Sharks 22 14 Thomas A Becket Junior School (Worthing) Southern Sharks 22 16 Catsfield Church of England Primary School (Battle) Hastings & Rother Leopards 21 Specsavers ‘Virtual’ Sussex School Games: The Winter Games Overall Leaderboard Primary Schools (19/02/2021) Position School SGO Area Team Points 16 Christ Church CofE Primary and Nursery Academy (St Leonards-on-Sea) Hastings & Rother Leopards 21 18 Elm Grove Primary School (Worthing) Southern Sharks 20 18 Ocklynge Junior School (Eastbourne) -

Bus Route 47 Cuckmere Valley Ramblerbus

47 Cuckmere Valley Ramblerbus Saturdays, Sundays & Public Holidays during British Summer Time (until 31 October 2021) An hourly circular service from Berwick station via Alfriston, Seaford, Seven Sisters Country Park, Litlington and Wilmington. Temporary Timetable during closure of Station Road, Berwick Service 47 is affected by the long term closure of Station Road, Berwick and will operate to the temporary timetable shown below. Wilmington is not served by this temporary timetable. Please check Service Updates for the latest information. 47 on Saturdays Train from Brighton & Lewes 0956 1756 Train from Eastbourne 0954 1754 ------ ------ Berwick Station 1000 1800 Berwick Crossroads 1005 1805 Berwick, Drusillas Park 1006 1806 Alfriston Market Cross 1010 1810 Alfriston, Frog Firle 1012 and 1812 High & Over Car Park 1014 then 1814 Chyngton Estate, Millberg Rd 1016 hourly 1816 Sutton Avenue, Arundel Rd 1016 until 1819 Seaford, Morrisons (near stn) 1021 1821 Seaford, Library 1022 1822 Seaford, Sutton Corner 1024 1824 Exceat, Cuckmere Inn 1027 1827 Seven Sisters Country Park Centre 1029 1829 Friston Forest, West Dean Car Pk 1031 1831 Litlington, Plough & Harrow 1035 1835 Lullington Corner 1037 1837 Drusillas Roundabout 1041 1841 Berwick Crossroads 1042 1842 Berwick Station 1047 1847 ------ ------ Train to Lewes & Brighton 1054 1854 Train to Eastbourne 1056 1856 Seaford trains: ------ ------ ... arrive from Brighton & Lewes 0948 1748 ... depart to Lewes & Brighton 1026 1826 In the rural area the bus will stop to pick up or set down wherever it is safe to do so. At Berwick Station the bus will wait for up to 5 minutes for a late running train. Train times may be different on Bank Holidays, please check before travelling. -

IDB Biodiversity Action Plan

BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN April 2018 PEVENSEY AND CUCKMERE WLMB – BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN Front cover images (L-R) Kestrel ©Heather Smithers; Barn Owl; Floating Pennywort; Fen Raft Spider ©Charlie Jackson; Water Vole; Otter PEVENSEY AND CUCKMERE WLMB – BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN FOREWORD This Biodiversity Action Plan has been prepared by the Pevensey and Cuckmere Water Level Management Board in accordance with the commitment in the Implementation Plan of the DEFRA Internal Drainage Board Review for IDB’s, to produce their own Biodiversity Action Plans by April 2010. This aims to align this BAP with the Sussex Biodiversity Action Plan. The document also demonstrates the Board’s commitment to fulfilling its duty as a public body under the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 to conserve biodiversity. Many of the Board’s activities have benefits and opportunities for biodiversity, not least its water level management and ditch maintenance work. It is hoped that this Biodiversity Action Plan will help the Board to maximise the biodiversity benefits from its activities and demonstrate its contribution to the Government’s UK Biodiversity Action Plan targets as part of the Biodiversity 2020 strategy. The Board has adopted the Biodiversity Action Plan as one of its policies and subject to available resources is committed to its implementation. It will review the plan periodically and update it as appropriate. Bill Gower Chairman of the Board PEVENSEY AND CUCKMERE WLMB – BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS 1 1