Desmosomes Pattern Cell Mechanics to Govern Epidermal Tissue Form and Function

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transgenic Cyclooxygenase-2 Overexpression Sensitizes Mouse Skin for Carcinogenesis

Transgenic cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression sensitizes mouse skin for carcinogenesis Karin Mu¨ ller-Decker*†, Gitta Neufang*, Irina Berger‡, Melanie Neumann*, Friedrich Marks*, and Gerhard Fu¨ rstenberger* *Research Program Tumor Cell Regulation, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, and ‡Department of Pathology, Ruprecht-Karls-University, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany Edited by Philip Needleman, Pharmacia Corporation, St. Louis, MO, and approved July 29, 2002 (received for review May 30, 2002) Genetic and pharmacological evidence suggests that overexpres- there is a causal relationship between COX-2 overexpression sion of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is critical for epithelial carcino- and tumor development. Recently, we have shown that the genesis and provides a major target for cancer chemoprevention keratin 5 (K5) promoter-driven overexpression of COX-2 in by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Transgenic mouse lines basal cells of interfollicular epidermis and the pilosebaceous unit with keratin 5 promoter-driven COX-2 overexpression in basal led to a preneoplastic skin phenotype in 4 of 4 high-expression epidermal cells exhibit a preneoplastic skin phenotype. As shown mouse lines (15). here, this phenotype depends on the level of COX-2 expression and To delineate COX-2 functions for carcinogenesis, we have COX-2-mediated prostaglandin accumulation. The transgenics did used the initiation–promotion model (2) for the induction of skin not develop skin tumors spontaneously but did so after a single tumors in wild-type (wt) NMRI mice and COX-2 transgenic application of an initiating dose of the carcinogen 7,12-dimethyl- mouse lines. This multistage model allows the analysis of the benz[a]anthracene (DMBA). Long-term treatment with the tumor carcinogenic process in terms of distinct stages, i.e., initiation by promoter phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, as required for tumor- application of a subcarcinogenic dose of a carcinogen such as igenesis in wild-type mice, was not necessary for transgenics. -

A Cell Line P53 Mutation Type UM

A Cell line p53 mutation Type UM-SCC 1 wt UM-SCC5 Exon 5, 157 GTC --> TTC Missense mutation by transversion (Valine --> Phenylalanine UM-SCC6 wt UM-SCC9 wt UM-SCC11A wt UM-SCC11B Exon 7, 242 TGC --> TCC Missense mutation by transversion (Cysteine --> Serine) UM-SCC22A Exon 6, 220 TAT --> TGT Missense mutation by transition (Tyrosine --> Cysteine) UM-SCC22B Exon 6, 220 TAT --> TGT Missense mutation by transition (Tyrosine --> Cysteine) UM-SCC38 Exon 5, 132 AAG --> AAT Missense mutation by transversion (Lysine --> Asparagine) UM-SCC46 Exon 8, 278 CCT --> CGT Missense mutation by transversion (Proline --> Alanine) B 1 Supplementary Methods Cell Lines and Cell Culture A panel of ten established HNSCC cell lines from the University of Michigan series (UM-SCC) was obtained from Dr. T. E. Carey at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. The UM-SCC cell lines were derived from eight patients with SCC of the upper aerodigestive tract (supplemental Table 1). Patient age at tumor diagnosis ranged from 37 to 72 years. The cell lines selected were obtained from patients with stage I-IV tumors, distributed among oral, pharyngeal and laryngeal sites. All the patients had aggressive disease, with early recurrence and death within two years of therapy. Cell lines established from single isolates of a patient specimen are designated by a numeric designation, and where isolates from two time points or anatomical sites were obtained, the designation includes an alphabetical suffix (i.e., "A" or "B"). The cell lines were maintained in Eagle's minimal essential media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. -

Plakoglobin Is Required for Effective Intermediate Filament Anchorage to Desmosomes Devrim Acehan1, Christopher Petzold1, Iwona Gumper2, David D

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Plakoglobin Is Required for Effective Intermediate Filament Anchorage to Desmosomes Devrim Acehan1, Christopher Petzold1, Iwona Gumper2, David D. Sabatini2, Eliane J. Mu¨ller3, Pamela Cowin2,4 and David L. Stokes1,2,5 Desmosomes are adhesive junctions that provide mechanical coupling between cells. Plakoglobin (PG) is a major component of the intracellular plaque that serves to connect transmembrane elements to the cytoskeleton. We have used electron tomography and immunolabeling to investigate the consequences of PG knockout on the molecular architecture of the intracellular plaque in cultured keratinocytes. Although knockout keratinocytes form substantial numbers of desmosome-like junctions and have a relatively normal intercellular distribution of desmosomal cadherins, their cytoplasmic plaques are sparse and anchoring of intermediate filaments is defective. In the knockout, b-catenin appears to substitute for PG in the clustering of cadherins, but is unable to recruit normal levels of plakophilin-1 and desmoplakin to the plaque. By comparing tomograms of wild type and knockout desmosomes, we have assigned particular densities to desmoplakin and described their interaction with intermediate filaments. Desmoplakin molecules are more extended in wild type than knockout desmosomes, as if intermediate filament connections produced tension within the plaque. On the basis of our observations, we propose a particular assembly sequence, beginning with cadherin clustering within the plasma membrane, followed by recruitment of plakophilin and desmoplakin to the plaque, and ending with anchoring of intermediate filaments, which represents the key to adhesive strength. Journal of Investigative Dermatology (2008) 128, 2665–2675; doi:10.1038/jid.2008.141; published online 22 May 2008 INTRODUCTION dense plaque that is further from the membrane and that Desmosomes are large macromolecular complexes that mediates the binding of intermediate filaments. -

Structural Heterogeneity of Cellular K5/K14 Filaments As Revealed by Cryo

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.12.442145; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Structural heterogeneity of cellular K5/K14 filaments as revealed by cryo- 2 electron microscopy 3 4 Short title: Structural heterogeneity of keratin filaments 5 6 7 Miriam S. Weber1, Matthias Eibauer1, Suganya Sivagurunathan2, Thomas M. Magin3, Robert D. 8 Goldman2, Ohad Medalia1* 9 1Department of Biochemistry, University of Zurich, Switzerland 10 2Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of 11 Medicine, USA 12 3Institute of Biology, University of Leipzig, Germany 13 14 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 15 16 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.12.442145; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 17 Abstract 18 Keratin intermediate filaments are an essential and major component of the cytoskeleton in epithelial 19 cells. They form a stable yet dynamic filamentous network extending from the nucleus to the cell 20 periphery. Keratin filaments provide cellular resistance to mechanical stresses, ensure cell and tissue 21 integrity in addition to regulatory functions. Mutations in keratin genes are related to a variety of 22 epithelial tissue diseases that mostly affect skin and hair. Despite their importance, the molecular 23 structure of keratin filaments remains largely unknown. In this study, we analyzed the structure of 24 keratin 5/keratin 14 filaments within ghost keratinocytes by cryo-electron microscopy and cryo- 25 electron tomography. -

P63 Transcription Factor Regulates Nuclear Shape and Expression of Nuclear Envelope

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 21 September 2017 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Rapisarda, Valentina and Malashchuk, Igor and Asamaowei, Inemo E. and Poterlowicz, Krzysztof and Fessing, Michael Y. and Sharov, Andrey A. and Karakesisoglou, Iakowos and Botchkarev, Vladimir A. and Mardaryev, Andrei (2017) 'p63 transcription factor regulates nuclear shape and expression of nuclear envelope-associated genes in epidermal keratinocytes.', Journal of investigative dermatology., 137 (10). pp. 2157-2167. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2017.05.013 Publisher's copyright statement: This article is available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). You may copy and distribute the article, create extracts, abstracts and new works from the article, alter and revise the article, text or data mine the article and otherwise reuse the article commercially (including reuse and/or resale of the article) without permission from Elsevier. You must give appropriate credit to the original work, together with a link to the formal publication through the relevant DOI and a link to the Creative Commons user license above. You must indicate if any changes are made but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use of the work. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. -

The Correlation of Keratin Expression with In-Vitro Epithelial Cell Line Differentiation

The correlation of keratin expression with in-vitro epithelial cell line differentiation Deeqo Aden Thesis submitted to the University of London for Degree of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) Supervisors: Professor Ian. C. Mackenzie Professor Farida Fortune Centre for Clinical and Diagnostic Oral Science Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry Queen Mary, University of London 2009 Contents Content pages ……………………………………………………………………......2 Abstract………………………………………………………………………….........6 Acknowledgements and Declaration……………………………………………...…7 List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………8 List of Tables………………………………………………………………………...12 Abbreviations….………………………………………………………………..…...14 Chapter 1: Literature review 16 1.1 Structure and function of the Oral Mucosa……………..…………….…..............17 1.2 Maintenance of the oral cavity...……………………………………….................20 1.2.1 Environmental Factors which damage the Oral Mucosa………. ….…………..21 1.3 Structure and function of the Oral Mucosa ………………...….……….………...21 1.3.1 Skin Barrier Formation………………………………………………….……...22 1.4 Comparison of Oral Mucosa and Skin…………………………………….……...24 1.5 Developmental and Experimental Models used in Oral mucosa and Skin...……..28 1.6 Keratinocytes…………………………………………………….….....................29 1.6.1 Desmosomes…………………………………………….…...............................29 1.6.2 Hemidesmosomes……………………………………….…...............................30 1.6.3 Tight Junctions………………………….……………….…...............................32 1.6.4 Gap Junctions………………………….……………….….................................32 -

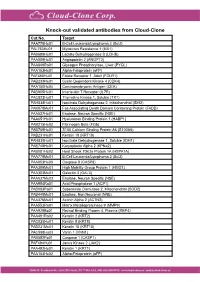

Knock-Out Validated Antibodies from Cloud-Clone Cat.No

Knock-out validated antibodies from Cloud-Clone Cat.No. Target PAA778Hu01 B-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) PAL763Hu01 Myxovirus Resistance 1 (MX1) PAB698Hu01 Lactate Dehydrogenase B (LDHB) PAA009Hu01 Angiopoietin 2 (ANGPT2) PAA849Ra01 Glycogen Phosphorylase, Liver (PYGL) PAA153Hu01 Alpha-Fetoprotein (aFP) PAF460Hu01 Folate Receptor 1, Adult (FOLR1) PAB233Hu01 Cyclin Dependent Kinase 4 (CDK4) PAA150Hu04 Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) PAB905Hu01 Interleukin 7 Receptor (IL7R) PAC823Hu01 Thymidine Kinase 1, Soluble (TK1) PAH838Hu01 Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 2, mitochondrial (IDH2) PAK078Mu01 Fas Associating Death Domain Containing Protein (FADD) PAA537Hu01 Enolase, Neuron Specific (NSE) PAA651Hu01 Hyaluronan Binding Protein 1 (HABP1) PAB215Hu02 Fibrinogen Beta (FGb) PAB769Hu01 S100 Calcium Binding Protein A6 (S100A6) PAB231Hu01 Keratin 18 (KRT18) PAH839Hu01 Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1, Soluble (IDH1) PAE748Hu01 Karyopherin Alpha 2 (KPNa2) PAB081Hu02 Heat Shock 70kDa Protein 1A (HSPA1A) PAA778Mu01 B-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) PAA853Hu03 Caspase 8 (CASP8) PAA399Mu01 High Mobility Group Protein 1 (HMG1) PAA303Mu01 Galectin 3 (GAL3) PAA537Mu02 Enolase, Neuron Specific (NSE) PAA994Ra01 Acid Phosphatase 1 (ACP1) PAB083Ra01 Superoxide Dismutase 2, Mitochondrial (SOD2) PAB449Mu01 Enolase, Non Neuronal (NNE) PAA376Mu01 Actinin Alpha 2 (ACTN2) PAA553Ra01 Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) PAA929Bo01 Retinol Binding Protein 4, Plasma (RBP4) PAA491Ra02 Keratin 2 (KRT2) PAC025Hu01 Keratin 8 (KRT8) PAB231Mu01 Keratin 18 (KRT18) PAC598Hu03 Vanin 1 (VNN1) -

Jonas SG Silvander: Keratins in the Endocrine Pancreas

Jonas S.G. Silvander Keratins in the endocrine pancreas - Novel regulators of cellular processes in β-cells This Ph.D. thesis describes the role of keratins in the endocrine pancreas. It shows that keratins are maintaining normal insulin levels by involvement Jonas S.G. Silvander | Keratins 2018 in the endocrine pancreas| Jonas S.G. Silvander in β-cell mitochondrial ATP production and insulin vesicle morphology. On systemic level, keratins in β-cells regulate basal blood glucose levels, most Keratins in the endocrine pancreas likely in combination with insulin sensitive tissues. In addition, keratins are crucial for β-cell stress - Novel regulators of cellular processes in β-cells protection against chemically induced T1D in mice. These novel findings on insulin production and cell stress protection in β-cells, shed light on the potential role of keratins in diabetes susceptibility and progression. The author graduated from Ålands Lyceum, Marie- hamn, in 2007. He recieved his M.Sc. in Biomedical Imaging from Åbo Akademi University in May 2013. Since August 2013, he has been working as a Ph.D. student in Diana Toivola’s Epithelial Biology Labora- tory at Åbo Akademi University. 9 789521 236648 ISBN 978-952-12-3664-8 Keratins in the endocrine pancreas - Novel regulators of cellular processes in β-cells Jonas S.G. Silvander Cell biology Faculty of Science and Engineering Åbo Akademi University Turku, Finland 2018 The research projects were conducted at Cell biology, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Åbo Akademi University. Supervised by Diana Toivola, Ph.D. Cell biology Faculty of Science and Engineering Åbo Akademi University Finland Reviewed by Emilia Peuhu, Ph.D. -

Topological Network Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes In

CANCER GENOMICS & PROTEOMICS 12 : 153-166 (2015) Topological Network Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in Cancer Cells with Acquired Gefitinib Resistance YOUNG SEOK LEE 1, SUN GOO HWANG 2, JIN KI KIM 1, TAE HWAN PARK 3, YOUNG RAE KIM 1, HO SUNG MYEONG 1, KANG KWON 4, CHEOL SEONG JANG 2, YUN HEE NOH 1 and SUNG YOUNG KIM 1 1Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Konkuk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2Plant Genomics Laboratory, Department of Applied Plant Science, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Republic of Korea; 3Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 4School of Korean Medicine, Pusan National University, Yangsan, Republic of Korea Abstract. Background/Aim: Despite great effort to elucidate into the complex mechanism of AGR and to novel gene the process of acquired gefitinib resistance (AGR) in order to expression signatures useful for further clinical studies. develop successful chemotherapy, the precise mechanisms and genetic factors of such resistance have yet to be elucidated. Although chemotherapy is the most common treatment for Materials and Methods: We performed a cross-platform meta- various cancer types, the development of acquired resistance analysis of three publically available microarray datasets to anticancer drugs remains a serious problem, leading to a related to cancer with AGR. For the top 100 differentially majority of patients who initially responded to anticancer expressed genes (DEGs), we clustered functional modules of drugs suffering the recurrence or metastasis of their cancer (1- hub genes in a gene co-expression network and a protein- 3). Acquired drug resistance (ADR) is known to have a multi- protein interaction network. -

Transient Activation of ß-Catenin Signaling in Cutaneous Keratinocytes Is Sufficient to Trigger the Active Growth Phase Of

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 29, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press RESEARCH COMMUNICATION Transient activation cogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3; for review, see Peifer  and Polakis 2000). This complex promotes phosphoryla- of -catenin signaling tion of -catenin at a number of N-terminal serine and in cutaneous keratinocytes is threonine residues, and the phosphorylated -catenin is ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded by the protea- sufficient to trigger the active some. growth phase of the hair cycle Binding of Wnts to their cognate frizzled and low-den- sity lipoprotein receptor-related protein receptor com- in mice plexes on the cell surface leads to inhibition of GSK-3 activity and increased levels of free -catenin in the cell David Van Mater,1 Frank T. Kolligs,2,6 (Peifer and Polakis 2000). In cancers, inactivating muta- Andrzej A. Dlugosz,3,5,7 and Eric R. Fearon1,2,4,5,8 tions in the APC or axin proteins or activating mutations affecting N-terminal phosphorylation sites in -catenin 1Departments of Human Genetics, 2Internal Medicine, lead to stabilization of -catenin (Polakis 2000). Regard- 3Dermatology, and 4Pathology, and the 5Cancer Center, less of whether Wnt signals or mutational defects stabi- University of Michigan School of Medicine, lize -catenin, following its accumulation in the cell, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA -catenin can complex in the nucleus with T cell factor/ lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) transcription regu- Wnts have key roles in many developmental processes, lators, leading to activation of TCF-regulated genes (a list including hair follicle growth and differentiation. Stabi- of candidate TCF target genes is provided at: http:// lization of -catenin is essential in the canonical Wnt www.stanford.edu/∼rnusse/wntwindow.html). -

Regulation of Keratin Filament Network Dynamics

Regulation of keratin filament network dynamics Von der Fakultät für Mathematik, Informatik und Naturwissenschaften der RWTH Aachen University zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom Biologe Marcin Maciej Moch aus Dzierżoniów (früher Reichenbach, NS), Polen Berichter: Universitätsprofessor Dr. med. Rudolf E. Leube Universitätsprofessor Dr. phil. nat. Gabriele Pradel Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 19. Juni 2015 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfügbar. This work was performed at the Institute for Molecular and Cellular Anatomy at University Hospital RWTH Aachen by the mentorship of Prof. Dr. med. Rudolf E. Leube. It was exclusively performed by myself, unless otherwise stated in the text. 1. Reviewer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. med. Rudolf E. Leube 2. Reviewer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. phil. nat. Gabriele Pradel Ulm, 15.02.2015 2 Publications Publications Measuring the regulation of keratin filament network dynamics. Moch M, and Herberich G, Aach T, Leube RE, Windoffer R. 2013. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110:10664-10669. Intermediate filaments and the regulation of focal adhesion. Leube RE, Moch M, Windoffer R. 2015. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 32:13–20. "Panta rhei": Perpetual cycling of the keratin cytoskeleton. Leube RE, Moch M, Kölsch A, Windoffer R. 2011. Bioarchitecture. 1:39-44. Intracellular motility of intermediate filaments. Leube RE, Moch M, Windoffer R. Under review in: The Cytoskeleton. Editors: Pollard T., Dutcher S., Goldman R. Cold Springer Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor. Multidimensional monitoring of keratin filaments in cultured cells and in tissues. Schwarz N, and Moch M, Windoffer R, Leube RE. -

Supplementary Material Contents

Supplementary Material Contents Immune modulating proteins identified from exosomal samples.....................................................................2 Figure S1: Overlap between exosomal and soluble proteomes.................................................................................... 4 Bacterial strains:..............................................................................................................................................4 Figure S2: Variability between subjects of effects of exosomes on BL21-lux growth.................................................... 5 Figure S3: Early effects of exosomes on growth of BL21 E. coli .................................................................................... 5 Figure S4: Exosomal Lysis............................................................................................................................................ 6 Figure S5: Effect of pH on exosomal action.................................................................................................................. 7 Figure S6: Effect of exosomes on growth of UPEC (pH = 6.5) suspended in exosome-depleted urine supernatant ....... 8 Effective exosomal concentration....................................................................................................................8 Figure S7: Sample constitution for luminometry experiments..................................................................................... 8 Figure S8: Determining effective concentration .........................................................................................................