Zograf 41 09 Bormpoudaki.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best of Greece

05_598317 ch01.qxd 10/5/05 11:06 PM Page 6 1 The Best of Greece Greece is, of course, the land of ancient sites and architectural treasures—the Acrop- olis in Athens, the amphitheater of Epidaurus, and the reconstructed palace at Knos- sos among the best known. But Greece is much more: It offers age-old spectacular natural sights, for instance—from Santorini’s caldera to the gray pinnacles of rock of the Meteora—and modern diversions ranging from elegant museums to luxury resorts. It can be bewildering to plan your trip with so many options vying for your attention. Take us along and we’ll do the work for you. We’ve traveled the country extensively and chosen the very best that Greece has to offer. We’ve explored the archaeological sites, visited the museums, inspected the hotels, reviewed the tavernas and ouzeries, and scoped out the beaches. Here’s what we consider the best of the best. 1 The Best Travel Experiences • Making Haste Slowly: Give yourself preparing you for the unexpected in time to sit in a seaside taverna and island boat schedules! See chapter 10, watch the fishing boats come and go. “The Cyclades.” If you visit Greece in the spring, take • Leaving the Beaten Path: Persist the time to smell the flowers; the against your body’s and mind’s signals fields are covered with poppies, that “this may be pushing too far,” daisies, and other blooms. Even in leave the main routes and major Athens, you’ll see hardy species attractions behind, and make your growing through the cracks in con- own discoveries of landscape, villages, crete sidewalks—or better yet, visit or activities. -

Memorial Services

BATTLE OF CRETE COMMEMORATIONS ATHENS & CRETE, 12-21 MAY 2019 MEMORIAL SERVICES Sunday, 12 May 2019 10.45 – Commemorative service at the Athens Metropolitan Cathedral and wreath-laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Syntagma Square Location: Mitropoleos Street - Syntagama Square, Athens Wednesday, 15 May 2019 08.00 – Flag hoisting at the Unknown Soldier Memorial by the 547 AM/TP Regiment Location: Square of the Unknown Soldier (Platia Agnostou Stratioti), Rethymno town Friday, 17 May 2019 11.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Army Cadets Memorial Location: Kolymbari, Region of Chania 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the 110 Martyrs Memorial Location: Missiria, Region of Rethymno Saturday, 18 May 2019 10.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Greeks Location: Latzimas, Rethymno Region 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Australian-Greek Memorial Location: Stavromenos, Region of Rethymno 13.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Greek-Australian Memorial | Presentation of RSL National awards to Cretan students Location: 38, Igoumenou Gavriil Str. (Efedron Axiomatikon Square), Rethymno town 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Inhabitants Location: 1, Kanari Coast, Nea Chora harbour, Chania town 1 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen & the Bust of Colonel Stylianos Manioudakis Location: Armeni, Region of Rethymno 19.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Peace Memorial for Greeks and Allies Location: Preveli, Region of Rethymno Sunday, 19 May 2019 10.00 – Official doxology Location: Presentation of Mary Metropolitan Church, Rethymno town 11.00 – Memorial service and wreath-laying at the Rethymno Gerndarmerie School Location: 29, N. -

Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Management of Water Resources in the Island of Crete, Greece

water Review Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Management of Water Resources in the Island of Crete, Greece V. A. Tzanakakis 1,2,*, A. N. Angelakis 3,4 , N. V. Paranychianakis 5, Y. G. Dialynas 6 and G. Tchobanoglous 7 1 Hellenic Agricultural Organization Demeter (HAO-Demeter), Soil and Water Resources Institute, 57001 Thessaloniki, Greece 2 Department of Agriculture, School of Agricultural Science, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Iraklion, 71410 Crete, Greece 3 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion, Greece 4 Union of Water Supply and Sewerage Enterprises, 41222 Larissa, Greece; [email protected] 5 School of Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Crete, 73100 Chania, Greece; [email protected] 6 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Cyprus, Nicosia 1678, Cyprus; [email protected] 7 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 April 2020; Accepted: 16 May 2020; Published: 28 May 2020 Abstract: Crete, located in the South Mediterranean Sea, is characterized by long coastal areas, varied terrain relief and geology, and great spatial and inter-annual variations in precipitation. Under average meteorological conditions, the island is water-sufficient (969 mm precipitation; theoretical water potential 3284 hm3; and total water use 610 hm3). Agriculture is by far the greatest user of water (78% of total water use), followed by domestic use (21%). Despite the high average water availability, water scarcity events commonly occur, particularly in the eastern-south part of the island, driven by local climatic conditions and seasonal or geographical mismatches between water availability and demand. -

Travel Itinerary for Your Trip to Greece Created by Mina Agnos

Travel Itinerary for your trip to Greece Created by Mina Agnos You have a wonderful trip to look forward to! Please note: Entry into the European countries in the Schengen area requires that your passport be valid for at least six months beyond your intended date of departure. Your Booking Reference is: ITI/12782/A47834 Summary Accommodation 4 nights Naxian Collection Luxury Villas & Suites 1 Luxury 2-Bedroom Villa with Private Pool with Breakfast Daily 4 nights Eden Villas Santorini 1 Executive 3-BR Villa with Outdoor Pool & Caldera View for Four with Breakfast Daily 4 nights Blue Palace Resort & Spa 1 2 Bedroom Suite with Sea View and Private Heated Pool for Four with Breakfast Daily Activity Naxos Yesterday & Today Private Transportation Local Guide Discover Santorini Archaeology & Culture Private Transportation Entrance Fees Local Guide Akrotiri Licensed Guide Knossos & Heraklion Discovery Entrance Fees Private Transportation Local Guide Spinalonga, Agios Nikolaos & Kritsa Discovery Entrance Fees Private Transportation Local Guide Island Escape and Picnic Transportation Private Helicopter from Mykonos to Naxos Transfer Between Naxos Airport & Stelida (Minicoach) Targa 37 at Disposal for 8 Days Transfer Between Naxos Port & Stelida (Minicoach) Santorini Port Transfer (Mini Coach) Santorini Port Transfer (Mini Coach) Transfer Between Plaka and Heraklion (Minivan) Transfer Between Plaka and Heraklion (Minivan) Day 1 Transportation Services Arrive in Mykonos. Private Transfer: Transfer Between Airport and Port (Minivan) VIP Assistance: VIP Port Assistance Your VIP Assistant will meet and greet you at the port, in which he will assist you with your luggage during ferry embarkation and disembarkation. Ferry: 4 passengers departing from Mykonos Port at 04:30 pm in Business Class with Sea Jets, arriving in Naxos Port at 05:10 pm. -

Memorial Services

BATTLE OF CRETE COMMEMORATIONS CRETE, 15-21 MAY 2018 MEMORIAL SERVICES Tuesday, 15 May 2018 11.00 – Commemorative service at the Agia Memorial at the “Brigadier Raptopoulos” military camp Location: Agia, Region of Chania Wednesday, 16 May 2018 08.00 – Flag hoisting at the Unknown Soldier Memorial by the 547 AM/TP Regiment Location: Square of the Unknown Soldier (Platia Agnostou Stratioti), Rethymno town 18.30 – Commemorative service at the Memorial to the Fallen Residents of Nea Chora Location: 1, Kanaris Coast, Nea Chora harbour, Chania town Thursday, 17 May 2018 10.30 – Commemorative service at the Australian-Greek Memorial Location: Stavromenos, Region of Rethymno 11.00 – Commemorative service at the Army Cadets Memorial (followed by speeches at the Orthodox Academy of Crete) Location: Kolymvari, Region of Chania 12.00 – Commemorative service at the Greek-Australian Memorial Location: 38, Igoumenou Gavriil Str., Rethymno town 18.00 – Commemorative service at the Memorial to the Fallen & the Bust of Colonel Stylianos Manioudakis Location: Armeni, Region of Rethymno 19.30 – Commemorative service at the Peace Memorial in Preveli Location: Preveli, Region of Rethymno 1 Friday, 18 May 2018 10.00 – Flag hoisting at Firka Fortress Location: Harbour, Chania town 11.30 – Commemorative service at the 110 Martyrs Memorial Location: Missiria, Region of Rethymno 11.30 – Military marches by the Military Band of the 5th Infantry Brigade Location: Harbour, Chania town 13.00 – Commemorative service at the Battle of 42nd Street Memorial Location: Tsikalaria -

Table of Contents 1

Maria Hnaraki, 1 Ph.D. Mentor & Cultural Advisor Drexel University (Philadelphia-U.S.A.) Associate Teaching Professor Official Representative of the World Council of Cretans Kids Love Greece Scientific & Educational Consultant Tel: (+) 30-6932-050-446 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Table of Contents 1. FORMAL EDUCATION ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. ADDITIONAL EDUCATION .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 3. EMPLOYMENT RECORD ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 3.1. Current Status (2015-…) ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 3.2. Employment History ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2.1. Teaching Experience ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 3.2.2. Research Projects .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Greek Tourism 2009 the National Herald, September 26, 2009

The National Herald a b September 26, 2009 www.thenationalherald.com 2 GREEK TOURISM 2009 THE NATIONAL HERALD, SEPTEMBER 26, 2009 RELIGIOUS TOURISM Discover The Other Face of Greece God. In the early 11th century the spring, a little way beyond, were Agios Nikolaos of Philanthropenoi. first anachorites living in the caves considered to be his sacred fount It is situated on the island of Lake in Meteora wanted to find a place (hagiasma). Pamvotis in Ioannina. It was found- to pray, to communicate with God Thessalonica: The city was ed at the end of the 13th c by the and devote to him. In the 14th cen- founded by Cassander in 315 B.C. Philanthropenoi, a noble Constan- tury, Athanassios the Meteorite and named after his wife, Thessa- tinople family. The church's fres- founded the Great Meteora. Since lonike, sister of Alexander the coes dated to the 16th c. are excel- then, and for more than 600 years, Great. Paul the Apostle reached the lent samples of post-Byzantine hundreds of monks and thousands city in autumn of 49 A.D. painting. Visitors should not miss in of believers have travelled to this Splendid Early Christian and the northern outer narthex the fa- holy site in order to pray. Byzantine Temples of very impor- mous fresco depicting the great The monks faced enormous tant historical value, such as the Greek philosophers and symboliz- problems due to the 400 meter Acheiropoietos (5th century A.D.) ing the union between the ancient height of the Holy Rocks. They built and the Church of the Holy Wisdom Greek spirit and Christianity. -

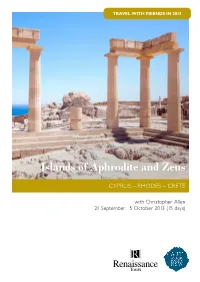

Islands of Aphrodite and Zeus

TRAVEL WITH FRIENDS IN 2013 Islands of Aphrodite and Zeus CYPRUS – RHODES – CRETE with Christopher Allen 21 September–5 October 2013 (15 days) Tour Islands of Aphrodite leader and Zeus Explore the history, civilisations and cultures of the most interesting of the islands of the Eastern Mediterranean: Cyprus, Rhodes and Crete. Where East meets West, these four islands are rich in history, ancient and modern, from the great Minoan states to the early Christian saints, from the Byzantine emperors to the Knights Templar, from the Venetians to the British. With Mediterranean expert Christopher Allen enjoy an in depth exploration of 10,000 years of history, civilisation, archaeology, art and architecture. At the same time, you will also discover some of Europe’s most beautiful landscapes, natural and man made, and enjoy the relaxed lifestyle, delicious cuisine and Christopher Allen warm hospitality of these glorious islands. Dr Christopher Allen is an art critic and historian who graduated from the University of Sydney and lectured at the National Art School in At a glance Sydney. He is currently Head of Art at Sydney Grammar • Leisurely stays in Cyprus, Rhodes and Crete School. Christopher is the author of many books, his • Cross the ‘Green Line’ from Greek Cyprus into Turkish Cyprus most recent Jeffrey Smart: unpublished paintings 1940- • Visit the Minoan sites of Knossos, Gournia, Malia and Gortyn 2007 (Melbourne, Australian Galleries) was published in 2008. • See the mythical birthplace of Aphrodite He was art critic of the Financial Review and is now national art • Exclusive stay at Kapsialiana Village, a historic village converted into a hotel critic for The Australian. -

Case Study #5: the Myrtoon Sea/ Peloponnese - Crete

Addressing MSP Implementation in Case Study Areas Case Study #5: The Myrtoon Sea/ Peloponnese - Crete Passage Deliverable C.1.3.8. Co-funded by the1 European Maritime and Fisheries Fund of the European Union. Agreement EASME/EMFF/2015/1.2.1.3/01/S12.742087 - SUPREME ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The work described in this report was supported by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund of the European Union- through the Grant Agreement EASME/EMFF/2015/1.2.1.3/01/S12.742087 - SUPREME, corresponding to the Call for proposal EASME/EMFF/2015/1.2.1.3 for Projects on Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP). DISCLAIMERS This document reflects only the authors’ views and not those of the European Union. This work may rely on data from sources external to the SUPREME project Consortium. Members of the Consortium do not accept liability for loss or damage suffered by any third party as a result of errors or inaccuracies in such data. The user thereof uses the information at its sole risk and neither the European Union nor any member of the SUPREME Consortium, are liable for any use that may be made of the information The designations employed and the presentation of material in the present document do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of UN Environment/MAP Barcelona Convention Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, area, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The depiction and use of boundaries, geographic names and related data shown on maps included in the present document are not warranted to be error free nor do they imply official endorsement or acceptance by UN Environment/ MAP Barcelona Convention Secretariat. -

Crete 6 Contents

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Crete Hania p54 Rethymno p104 Iraklio p143 Lasithi p188 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Alexis Averbuck, Kate Armstrong, Korina Miller, Richard Waters PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Crete . 4 HANIA . 54 Argyroupoli . 117 Crete Map . 6 Hania . 56 The Hinterland & Mt Psiloritis . .. 119 Crete’s Top 15 . 8 East of Hania . 69 Moni Arkadiou . 119 Akrotiri Peninsula . 69 Need to Know . 16 Eleftherna . 121 Aptera . 71 First Time Crete . 18 Margarites . 121 Armenoi & Around . 71 Perama to Anogia . 122 If You Like… . 20 Almyrida . 71 Anogia . 123 Month by Month . 22 Vamos . 72 Mt Psiloritis . 124 Itineraries . 24 Gavalohori . 72 Coast to Coast . 125 Outdoor Activities . 32 Georgioupoli . 73 Armeni . 125 Lake Kournas . 73 Eat & Drink Spili . 125 Like a Local . 41 Vryses . 74 Southern Coast . 126 Travel with Children . 49 Southwest Coast & Sfakia . 74 Plakias . 127 Regions at a Glance . .. 51 Askyfou . 75 Preveli . 130 Imbros Gorge . 75 Beaches Between Plakias & Agia Galini . 131 Frangokastello . 76 Agia Galini . 132 CREATAS IMAGES / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / IMAGES CREATAS Hora Sfakion . 77 Northeastern Coast . 133 Loutro . 79 Panormo . 133 Agia Roumeli . 80 Bali . 135 Sougia . 81 Lissos . 83 Paleohora . 83 IRAKLIO . 143 Elafonisi . 88 Iraklio . 146 Hrysoskalitissas . 88 Around Iraklio . 157 Gavdos Island . 89 Knossos . 157 Lefka Ori West of Iraklio . 162 VENETIAN HARBOUR, & Samaria Gorge . 91 Agia Pelagia . 162 RETHYMNO P107 Hania to Omalos . 91 Fodele . 162 Omalos . 92 Arolithos . 162 Samaria Gorge . 94 Central Iraklio . 163 ALAN BENSON / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / BENSON ALAN Northwest Coast . 95 Arhanes & Around . 163 Innahorion Villages . -

Crete (Chapter)

Greek Islands Crete (Chapter) Edition 7th Edition, March 2012 Pages 56 Page Range 256-311 PDF Coverage includes: Central Crete, Iraklio, Cretaquarium, Knossos, Arhanes, Zaros, Matala, Rethymno, Moni Arkadiou, Anogia, Mt Psiloritis, Spili, Plakias & around, Beaches Between Plakias & Agia Galini, Agia Galini, Western Crete, Hania & around, Samaria Gorge, Hora Sfakion & around, Frangokastello, Anopoli & Inner Sfakia, Sougia, Paleohora, Elafonisi, Gavdos Island, Kissamos-Kastelli & around, Eastern Crete, Lasithi Plateau, Agios Nikolaos & around, Mohlos, Sitia & around, Kato Zakros & Ancient Zakros, and Ierapetra & around. Useful Links: Having trouble viewing your file? Head to Lonely Planet Troubleshooting. Need more assistance? Head to the Help and Support page. Want to find more chapters? Head back to the Lonely Planet Shop. Want to hear fellow travellers’ tips and experiences? Lonely Planet’s Thorntree Community is waiting for you! © Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd. To make it easier for you to use, access to this chapter is not digitally restricted. In return, we think it’s fair to ask you to use it for personal, non-commercial purposes only. In other words, please don’t upload this chapter to a peer-to-peer site, mass email it to everyone you know, or resell it. See the terms and conditions on our site for a longer way of saying the above - ‘Do the right thing with our content. ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Crete Why Go? Iraklio ............................ 261 Crete (Κρήτη) is in many respects the culmination of the Knossos ........................268 Greek experience. Nature here has been as prolifi c as Picas- Rethymno ..................... 274 so in his prime, creating a dramatic quilt of big-shouldered Anogia ......................... -

His Holiness the Dalai Lama to Visit Ub

OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO UBUB INTERNAINTERNATIONALTIONAL UB INTERNATIONAL UBUB INTERNAINTERNAFALLTIONALTIONAL 2005 VOL. XIV, NO. 2 CONTENTS HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA TO VISIT UB CIO Honored in Latvia....2 he University at Buffalo (UB) is busy he expressed a special interest in UB’s inter- preparing for the landmark visit national character and outreach,” Dunnett President's Trip to Asia....3 TSeptember 18-20, 2006 by His Holi- said. “He sees the purpose of a visit to UB as ness Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai primarily educational in nature, and is keen Chinese Art Exhibition....5 Lama. to speak to our students and faculty. In fact, “We are thrilled that he made a special His Holiness has gener- request that a pri- External Affairs VP............6 ously accepted our invi- vate audience be tation,” said Stephen arranged with our Extreme Events ...............7 C. Dunnett, vice pro- international stu- vost for international dents.” Indo-U.S. Collaboration..9 education. Major uni- During meetings versities around the at the Office of Ti- country vie for the bet, His Holiness’s Science Education in honor of hosting The official representa- Rural India....................10 Dalai Lama, and we tive in New York are singularly fortunate City, Dunnett and Flu Pandemic..................12 in being chosen.” William J. Regan, di- “This is a major rector of confer- Paras Prasad..................13 event not only for the ences and special university but also for events, concluded Western New York,” an agreement on CIRRIE Funding.............14 Dunnett said. “The the terms and ar- Dalai Lama is revered rangements of the Immigration Director...15 around the world as visit.