The Wildlife Trusts (AB52)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let Nature Help 2020 Warwickshire

Let nature How nature’s recovery is essentialhelp for tackling the climate crisis Let nature help PA Wire/PA Images GettyGetes Images Julie Hatcher Peter Cairns/2020Vision The time is now Contents To deal with the climate crisis, we must bring nature back on an ambitious scale 4 Nature-based solutions The natural systems that lock carbon away safely he world is starting to take Rapid cuts in our emissions must We must act now and we must note of the threat of climate be matched with determined action get this right. According to the 6 What nature can do T “Emission cuts must The multiple benefits of giving nature a chance catastrophe. In response, the be matched with to fix our broken ecosystems, Intergovernmental Panel UK government has joined many so they can help stabilise our climate. on Climate Change (IPCC), 8 Case study 1 governments around the world in action to fix our We must bring nature back across at decisions we take in the Beaver reintroduction, Argyll setting a net zero emissions target in broken ecosystems, so least 30% of land and sea by 2030. next 10 years are crucial for law. they can help Restoring wild places will also avoiding total climate 9 Case study 2 The Great Fen Project, Cambridgeshire Yet we cannot tackle the climate stabilise our climate.” revive the natural richness we all catastrophe. We must crisis without similar ambition to depend upon, making our lives kickstart nature’s recovery 10 Case study 3 meet the nature crisis head on – the happier and healthier. -

The Direct and Indirect Contribution Made by the Wildlife Trusts to the Health and Wellbeing of Local People

An independent assessment for The Wildlife Trusts: by the University of Essex The direct and indirect contribution made by The Wildlife Trusts to the health and wellbeing of local people Protecting Wildlife for the Future Dr Carly Wood, Dr Mike Rogerson*, Dr Rachel Bragg, Dr Jo Barton and Professor Jules Pretty School of Biological Sciences, University of Essex Acknowledgments The authors are very grateful for the help and support given by The Wildlife Trusts staff, notably Nigel Doar, Cally Keetley and William George. All photos are courtesy of various Wildlife Trusts and are credited accordingly. Front Cover Photo credits: © Matthew Roberts Back Cover Photo credits: Small Copper Butterfly © Bob Coyle. * Correspondence contact: Mike Rogerson, Research Officer, School of Biological Sciences, University of Essex, Wivenhoe Park, Colchester CO4 3SQ. [email protected] The direct and indirect contribution made by individual Wildlife Trusts on the health and wellbeing of local people Report for The Wildlife Trusts Carly Wood, Mike Rogerson*, Rachel Bragg, Jo Barton, Jules Pretty Contents Executive Summary 5 1. Introduction 8 1.1 Background to research 8 1.2 The role of the Wildlife Trusts in promoting health and wellbeing 8 1.3 The role of the Green Exercise Research Team 9 1.4 The impact of nature on health and wellbeing 10 1.5 Nature-based activities for the general public and Green Care interventions for vulnerable people 11 1.6 Aim and objectives of this research 14 1.7 Content and structure of this report 15 2. Methodology 16 2.1 Survey of current nature-based activities run by individual Wildlife Trusts and Wildlife Trusts’ perceptions of evaluating health and wellbeing. -

Spaces Wild, London Wildlife Trust

SPACES WILD championing the values of London’s wildlife sites Protecting London’s wildlife for the future Foreword London is a remarkably green city supporting a wide diversity of habitats and species. Almost half of its area is blue and green space, and almost a fifth – covering over 1,500 different sites - is of sufficient value to biodiversity to be identified worthy of protection. These wildlife sites consist of much more than nature reserves, ranging from wetlands to chalk downs that are often valued by the local community for uses other than habitat. They have been established for almost 30 years, and as a network they provide the foundations for the conservation and enhancement of London’s wildlife, and the opportunity for people to experience the diversity of the city’s nature close to hand. They are a fantastic asset, but awareness of wildlife sites – the Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) – is low amongst the public (compared to, say, the Green Belt). There is understandable confusion between statutory wildlife sites and those identified through London’s planning process. In addition the reasons why SINCs have been identified SINCs cover 19.3% of the are often difficult to find out. With London set to grow to 10 million people by 2030 the pressures on our wildlife Greater London area sites will become profound. I have heard of local authorities being forced to choose between saving a local park and building a school. Accommodating our growth without causing a decline in the quality of our natural assets will be challenging; we have a target to build an estimated 42,000 homes a year in the capital merely to keep up with demand. -

Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31St March 2020

Company no 1600379 Charity no 283895 LONDON WILDLIFE TRUST (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Report and Financial Statements For the year ended 31st March 2020 CONTENTS Pages Trustees’ Report 2-9 Reference and Administrative Details 10 Independent Auditor's Report 11-13 Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 14 Consolidated and Charity Balance sheets 15 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 16 Notes to the accounts 17-32 1 London Wildlife Trust Trustees’ report For the year ended 31st March 2020 The Board of Trustees of London Wildlife Trust present their report together with the audited accounts for the year ended 31 March 2020. The Board have adopted the provisions of the Charities SORP (FRS 102) – Accounting and Reporting by Charities: Statement of Recommended practice applicable to charities preparing their accounts in accordance with the Financial Reporting Standard applicable in the UK and Republic of Ireland (effective 1 January 2015) in preparing the annual report and financial statements of the charity. The accounts have been prepared in accordance with the Companies Act 2006. Our objectives London Wildlife Trust Limited is required by charity and company law to act within the objects of its Articles of Association, which are as follows: 1. To promote the conservation, creation, maintenance and study for the benefit of the public of places and objects of biological, geological, archaeological or other scientific interest or of natural beauty in Greater London and elsewhere and to promote biodiversity throughout Greater London. 2. To promote the education of the public and in particular young people in the principles and practice of conservation of flora and fauna, the principles of sustainability and the appreciation of natural beauty particularly in urban areas. -

Annual Report & Accounts 2012-13

Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts Annual Report & Accounts 2012/13 Registered charity number: 207238 Version: 07/10/2013 10:17:20 Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts CONTENTS for the year ended 31 March 2013 Page Chair‟s Report 2 Chair of TWT England‟s Report 3 Trustees‟ Report 4-19 Auditor‟s Report 20-21 Accounting Policies 22-23 Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 24 Consolidated and Society Balance Sheets 25 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 26 Notes to the Financial Statements 27-39 The following pages do not form part of the statutory financial statements: Appendix: Grant Expenditure by Organisation 40-47 Page | 1 Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts CHAIR‟S REPORT for the year ended 31 March 2013 It has been an „eventful‟ year for me, my first as appointment. It is clear that the movement owes Chair of our 100-year-old movement. It all started them a great debt. with a bang - our tremendous centenary celebration at the Natural History Museum. At this It seems to me that this dynamic, creative event we traced our history back to our founder, movement is as united and effective as ever. Charles Rothschild, and awarded our medal in his, and his daughter Miriam‟s name, to philanthropist Peter De Haan. There were other occasions for celebration as well, including Sir David Attenborough presenting our centenary medal to Ted Smith, the father of the modern Wildlife Trust movement. There was also a gathering of one hundred of our most committed people from across the UK at Highgrove where our Patron HRH The Prince of Wales recognised their achievements. -

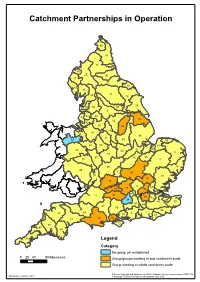

Catchment Partnerships in Operation

Catchment Partnerships in Operation 100 80 53 81 89 25 90 17 74 26 67 33 71 39 16 99 28 99 56 95 2 3 20 30 37 18 42 42 85 29 79 79 15 43 91 96 21 83 38 50 61 69 51 51 59 92 62 6 73 97 45 55 75 7 88 24 98 8 82 60 10 84 12 9 57 87 77 35 66 66 78 40 5 32 78 49 35 14 34 49 41 70 94 44 27 76 58 63 1 48 23 4 13 22 19 46 72 31 47 64 93 Legend Category No group yet established 0 20 40 80 Kilometres GSurobu cpa/gtcrhomupesn wt orking at sub catchment scale WGrhooulpe wcaotrckhinmge antt whole catchment scale © Crown Copyright and database right 2013. Ordnance Survey licence number 100024198. Map produced October 2013 © Copyright Environment Agency and database right 2013. Key to Management Catchment ID Catchment Sub/whole Joint ID Management Catchment partnership catchment Sub catchment name RBD Category Host Organisation (s) 1 Adur & Ouse Yes Whole South East England Yes Ouse and Adur Rivers Trust, Environment Agency 2 Aire and Calder Yes Whole Humber England No The Aire Rivers Trust 3 Alt/Crossens Yes Whole North West England No Healthy Waterways Trust 4 Arun & Western Streams Yes Whole South East England No Arun and Rother Rivers Trust 5 Bristol Avon & North Somerset Streams Yes Whole Severn England Yes Avon Wildlife Trust, Avon Frome Partnership 6 Broadland Rivers Yes Whole Anglian England No Norfolk Rivers Trust 7 Cam and Ely Ouse (including South Level) Yes Whole Anglian England Yes The Rivers Trust, Anglian Water Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife 8 Cherwell Yes Whole Thames England No Trust 9 Colne Yes Whole Thames England -

The Status of England's Local Wildlife Sites 2018

The status of England’s Local Wildlife Sites 2018 Report of results Protecting Wildlife for the Future Northumberland LWS, Naomi Waite Status of Local Wildlife Site Systems 2017 The Wildlife Trusts believe that people are part of nature; everything we value ultimately comes from it and everything we do has an impact on it. Our mission is to bring about living landscapes, living seas and a society where nature matters. The Wildlife Trusts is a grassroots movement of people from a wide range of backgrounds and all walks of life, who believe that we need nature and nature needs us. We have more than 800,000 members, 40,000 volunteers, 2,000 staff and 600 trustees. For more than a century we have been saving wildlife and wild places, increasing people’s awareness and understanding of the natural world, and deepening people’s relationship with it. We work on land and sea, from mountain tops to the seabed, from hidden valleys and coves to city streets. Wherever you are, Wildlife Trust people, places and projects are never far away, improving life for wildlife and people together, within communities of which we are a part. We look after more than 2,300 nature reserves, covering 98,500 hectares, and operate more than 100 visitor and education centres in every part of the UK, on Alderney and the Isle of Man. Acknowledgements We wish to extend our thanks to everyone who took the time to complete a questionnaire. Thank you also to Gertruda Stangvilaite, for helping to coordinate the survey during her time volunteering with The Wildlife Trusts. -

Creating a Nature Recovery Network to Bring Back Wildlife to Every Neighbourhood

Towards A Wilder Britain Creating a Nature Recovery Network to bring back wildlife to every neighbourhood A report for the Westminster Government by The Wildlife Trusts Nature Recovery Network We all The common lizard used to live up to its name. It could need nature do again It’s time to give it the space it needs to be part of all our lives Contents t a time when Britain stands 4 Britain in 2040 on the brink of its biggest It could be healthier, happier and greener – if we take A ever shake-up of the right decisions now environmental rules, The Wildlife Trusts are calling for a wilder, better 6 Britain in 2018 Britain. A lack of joined-up thinking has produced a raft of Most people agree that wildlife social and environmental problems and wild places are valuable for their own sake. We now know from 8 The solution: a Nature Recovery Network research across the globe that a Local networks of places that are good for wildlife, joined healthy, wildlife-rich natural world is together into a national Nature Recovery Network essential for our wellbeing and prosperity. 12 How the network can become reality But wildlife has been getting less A combination of strong new laws, nature maps and a and less common, on land and at change in our national culture to value nature once more sea, for decades. Wild places are The Wildlife Trusts more scarce, smaller and more 14 Pioneer project: the Aire Valley, Yorkshire Tel: 01636 670000 isolated. There is less nature and How a Nature Recovery Network would strengthen the local economy Email: [email protected] Website: wildlifetrusts.org greenery in the places where we @WildlifeTrusts live and work. -

Let Nature Help

Let nature How nature’s recovery is essentialhelp for tackling the climate crisis Let nature help PA Wire/PA Images Getty Images Julie Hatcher Peter Cairns/2020Vision The time is now Contents To deal with the climate crisis, we must bring nature back on an ambitious scale 4 Nature-based solutions The natural systems that lock carbon away safely he world is starting to take Rapid cuts in our emissions must We must act now and we note of the threat of climate “Emission cuts be matched with determined action must get this right. According 6 What nature can do T catastrophe. In response, to fix our broken ecosystems, so to the Intergovernmental Panel The multiple benefits of giving nature a chance the UK government has joined must be matched they can help stabilise our climate. on Climate Change (IPCC), with action to fix 8 Case study 1 many governments around the We must bring nature back across decisions we take in the next Beaver reintroduction, Argyll world in setting a net zero our broken at least 30% of land and sea by 10 years are crucial for emissions target in law. ecosystems, so they 2030. Restoring wild places will avoiding total climate 9 Case study 2 The Great Fen Project, Cambridgeshire Yet we cannot tackle the climate can help stabilise also revive the natural richness we catastrophe. We must crisis without similar ambition to our climate.” all depend upon, making our lives kickstart nature’s recovery 10 Case study 3 meet the nature crisis head on – the happier and healthier. -

Your Fundraising Toolkit Andisaregistered Charityno.210807

Your Fundraising Toolkit Bring some wild fun into your office and fundraise with your colleagues! Yorkshire Wildlife Trust is registered in England no. 409650 and is a registered charity no. 210807. Registered Office: 1 St George’s Place, York, YO24 1GN CARTER KIRSTEN Together with our supporters and We want to inspire everyone to have a volunteers, we are committed to stronger connection with nature; from creating a Yorkshire rich in wildlife for nature tots to guided walks we enable the benefit of everyone. From saving more people to learn about and love our wildlife and wild places to bringing Yorkshire’s wildlife. We are also part of people closer to nature, we have a vision The Wildlife Trusts enabling us to work of a wilder future. both nationally and locally to influence planning, policy and legislation to ensure Yorkshire Wildlife Trust manages over a brighter, more considered future for 100 nature reserves across Yorkshire: Yorkshire’s wildlife. from the iconic and internationally- important ‘seabird city’ at Flamborough Unfortunately wildlife and the Cliffs in the East, to the great upland environment is trouble! ‘15% of species swathes of carbon-capturing peatland, [are] now threatened with extinction we actively manage these wonderfully from Great Britain’1 and ‘all the top 10 wild places to ensure wildlife can thrive. warmest years since records began have occurred post-1990’. Across Yorkshire, We work across Yorkshire together agricultural intensification, urban with a range of partners to protect and development and climate change have connect even more of Yorkshire’s wild all had an impact on our wild places places giving wildlife the freedom to over the last century. -

100 Years of the Wildlife Trusts: a Potted History

100 years of The Wildlife Trusts: a potted history 1912-15: Charles Rothschild and the move to protect wild places On 16 May 1912, a banker, expert entomologist and much-travelled naturalist named Charles Rothschild formed the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves (SPNR) in order to identify and protect the UK’s best places for wildlife. The SPNR would later become The Wildlife Trusts. At that time, concern for nature focussed on protecting individual species from cruelty and exploitation, but Rothschild’s vision was to safeguard the places where wildlife lived – the moors, meadows, woods and fens under attack from rapid modernisation. In 1910, at the age of 33, Rothschild had bought 339 acres of wild fenland in Cambridgeshire, which later became the SPNR’s first nature reserve. From its base at the Natural History Museum in London, the SPNR started putting Rothschild’s vision into practice. By 1915, Rothschild and his colleagues – among them future Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain – had prepared a list of 284 special wildlife sites around the British Isles they considered ‘worthy of permanent preservation’, and presented this to the Board of Agriculture. The list of potential reserves included the Farne Islands and the Norfolk Broads in England, Tregaron Bog in Wales, Caen Lochan Glen in Scotland, and Lough Neagh in Ireland.1 However, despite Rothschild’s efforts he became ill and the list was not adopted by government. It would take many more years for the protection of wild places to make it onto the statute. 1920s-50s: The National Parks & Access to the Countryside Act and the birth of local Wildlife Trusts Rothschild died early, in 1923 at the age of 46, and stewardship of the SPNR passed to another visionary – a retired gemologist from the Natural History Museum named Herbert Smith. -

Partners and Funders Our Partners

Partners and Funders The Dynamic Dunescapes project wouldn't be possible without our partners and funders Dynamic Dunescapes is a £10m partnership project between 7 organisations and is funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the EU LIFE Programme, and the project partners. Our partners Work at each of our dune sites is supported and managed by one or two of our project partners. Use the links below to find out more about each of our partners and the great work that they do. We work closely to ensure that learnings and support are shared Natural England Natural England is the government’s adviser for the natural environment in England, helping to protect England’s nature and landscapes for people to enjoy and for the services they provide, by creating partnerships for nature's recovery. It is an executive non-departmental public body, sponsored by DEFRA. Visit Natural England’s website Plantlife Plantlife works nationally and internationally to celebrate and save threatened wild flora and landscapes. In partnership with landowners, conservation organisations, businesses, local communities and governments, the charity conserves our rarest species and ensures familiar flowers thrive. Visit Plantlife’s website National Trust National Trust is an independent charity and membership organisation for environmental and heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, looking after the places you love, from houses and buildings to the coast and countryside. Visit National Trust’s website Natural Resources Wales Natural Resources Wales are a Welsh Government Sponsored Body, looking after our environment for people and nature. NRW ensure that the natural resources of Wales are sustainably maintained, enhanced and used, now and in the future.