Toward a Living Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Native Plant Press

Native Plant Press January 2020 The Native Plant Press The Newsletter of the Central Puget Sound Chapter of WNPS Volume 21 No. 11 January 2020 Holiday Party Recap On Sunday, December 8th, the Central Puget Sound Chapter held our annual holiday party. The event was a potluck, and the fare was wide-ranging and excellent. The native plant-focused silent auction offered several hand-made wreaths, numerous potted natives from tiny succulents to gangly shrubs, plant-themed books and ephemera, and a couple of experiences. The selection occasioned some intense bidding wars, with Franja Bryant and Sharon Baker arriving at a compromise in their battle over the Native Garden Tea Party. A highlight of the party was the presentation of awards to Member, Steward and Professional of the Year. Each year, nominations are submitted by members and the recipients are chosen by the CPS Board. Stewart Wechsler (left) was chosen Member of the Year. Stewart is a Botany Fellow for the chapter and for many years has offered well-attended plant ID sessions before our westside meetings. In addition, he often fields the many botanical questions that we receive from the public. David Perasso (center) is our Steward of the Year. David is a Native Plant Steward at Martha Washington Park on Lake Washington and has been working to restore the historic oak/camas prairie ecosystem at the site. The site is now at the stage where David was able to host a First Nation camas harvest recently. He is also an active volunteer at our native plant nursery, providing vital expertise in the identification and propagation of natives. -

Food Forests: Their Services and Sustainability

Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development ISSN: 2152-0801 online https://foodsystemsjournal.org Food forests: Their services and sustainability Stefanie Albrecht a * Leuphana University Lüneburg Arnim Wiek b Arizona State University Submitted July 29, 2020 / Revised October 22, 2020, and February 8, 2021 / Accepted Febuary 8, 2021 / Published online July 10, 2021 Citation: Albrecht, S., & Wiek, A (2021). Food forests: Their services and sustainability. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 10(3), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2021.103.014 Copyright © 2021 by the Authors. Published by the Lyson Center for Civic Agriculture and Food Systems. Open access under CC-BY license. Abstract detailed insights on 14 exemplary food forests in Industrialized food systems use unsustainable Europe, North America, and South America, practices leading to climate change, natural gained through site visits and interviews. We resource depletion, economic disparities across the present and illustrate the main services that food value chain, and detrimental impacts on public forests provide and assess their sustainability. The health. In contrast, alternative food solutions such findings indicate that the majority of food forests as food forests have the potential to provide perform well on social-cultural and environmental healthy food, sufficient livelihoods, environmental criteria by building capacity, providing food, services, and spaces for recreation, education, and enhancing biodiversity, and regenerating soil, community building. This study compiles evidence among others. However, for broader impact, food from more than 200 food forests worldwide, with forests need to go beyond the provision of social- cultural and environmental services and enhance a * Corresponding author: Stefanie Albrecht, Doctoral student, their economic viability. -

City of Seattle Edward B

City of Seattle Edward B. Murray, Mayor Finance and Administrative Services Fred Podesta, Director July 25, 2016 The Honorable Tim Burgess Seattle City Hall 501 5th Ave. Seattle, WA 98124 Councilmember Burgess, Attached is an annual report of all real property under City ownership. The annual review supports strategic management of the City’s real estate holdings. Because City needs change over time, the annual review helps create opportunities to find the best municipal use of each property or put it back into the private sector to avoid holding properties without an adopted municipal purpose. Each January, FAS initiates the annual review process. City departments with jurisdiction over real property assure that all recent acquisitions and/or dispositions are accurately represented, and provide current information about each property’s current use, and future use, if identified. Each property is classified based on its level of utilization -- from Fully Utilized Municipal Use to Surplus. In addition, in 2015 and 2016, in conjunction with CBO, OPI, and OH, FAS has been reviewing properties with the HALA recommendation on using surplus property for housing. The attached list has a new column that groups excess, surplus, underutilized and interim use properties into categories to help differentiate the potential for various sites. Below is a matrix which explains the categorization: Category Description Difficult building site Small, steep and/or irregular parcels with limited development opportunity Future Use Identified use in the future -

The Cape Verde Project: Teaching Ecologically Sensitive and Socially

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2014 The aC pe Verde Project: Teaching Ecologically Sensitive and Socially Responsive Design N Jonathan Unaka University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Architecture Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Unaka, N Jonathan, "The aC pe Verde Project: Teaching Ecologically Sensitive and Socially Responsive Design" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 572. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/572 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING ECOLOGICALLY SENSITIVE AND SOCIALLY RESPONSIVE DESIGN THE CAPE VERDE PROJECT by N Jonathan Unaka A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August, 2014 Abstract TEACHING ECOLOGICALLY SENSITIVE AND SOCIALLY RESPONSIVE DESIGN THE CAPE VERDE PROJECT by N Jonathan Unaka The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, August, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor D Michael Utzinger This dissertation chronicles an evolving teaching philosophy. It was an attempt to develop a way to teach ecological design in architecture informed by ethical responses to ecological devastation and social injustice. The world faces numerous social and ecological challenges at global scales. Recent Industrialization has brought about improved life expectancies and human comforts, coinciding with expanded civic rights and personal freedom, and increased wealth and opportunities. -

Overview of Future Trends in Mobility and Spatial Development And

REPORT SPINTRENDS Overview of future trends in mobility and spatial development Overview of innovative measures / concepts to deal with growing mobility demand May 2019 V02 SPINTRENDS - SPace and INfrastructure TRENDS CEDR Call 2017: Collaborative Planning IMPRESSUM Title SPINTRENDS Overview of future trends in mobility and spatial development Overview of innovative measures / concepts to deal with growing mobility demand Project number 867460 Revision v02 Date 22.05.2019 Authors Gernot Lenz (AIT) Martin Reinthaler (AIT) Johannes Asamer (AIT) Ricardo Poppeliers (Ecorys) Danny Schipper (Ecorys) Tertius Hanekamp (TEMAH) Robert Broesi (MUST) V02 | 2 SPINTRENDS - SPace and INfrastructure TRENDS CEDR Call 2017: Collaborative Planning CONTENTS Impressum .......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Context .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 The project SPINTRENDS – a study on SPace and INfrastructure TRENDS ........................................................ 5 1.3 This report ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Written Testimony Submitted for the PBMVC May 24Th Meeting's Public

Written testimony submitted for the PBMVC May 24th meeting’s public hearing on potential pedestrian and bicycle projects the City should consider undertaking in the 2012-2014 Capital Budget: -----Original Message----- From: Burke O'Neal [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Friday, May 06, 2011 9:57 AM To: Traffic Cc: Amanda Werhane Subject: PEDESTRIAN-BICYCLE PROJECTS SOUGHT Hello, Here is my suggestion. For the Isthmus Bike Path I would like to see cross traffic on minor roads have stop signs that also state bike path traffic does not stop. It seems ridiculous to have bicyclists slowing down and/or stopping at every block for cross traffic. In my opinion, this should be more like a bike freeway from Baldwin to Blair St. with only stop signs for bikes on busy roads where the stop signs already exist. Sincerely, Burke Burke O'Neal Full Spectrum Solar 1240 E. Washington Ave. Madison, WI 53703 (608) 284-9495 From: Dipesh Navsaria, MPH, MSLIS, MD [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Friday, May 13, 2011 3:02 PM To: Traffic Subject: Ped-Bike Project Suggestion Good afternoon. I would love to see a bicycle path connector going from the Mineral Point/Speedway intersection (or perhaps a bit further north) connecting the Sunset Village neighborhood to the SW bike path. It's difficult to get around the intersection of Regent/Highland/Speedway over to the SW path, and going south to Glenway isn't the most direct route either. If there was a way to place a path at the border of Forest Hill Cemetery and Glenway Golf Course connecting to the SW path, it would keep users coming from directly west (Sunset Village/Hill Farms/etc) having to divert north or south through tricky intersections. -

Open House Summary May 22, 2008

Open House Summary May 22, 2008 Treasure Valley High Capacity Transit Study Summary of Open House Participant Comments Treasure Valley High Capacity Transit Study Summary of Open House Participant Comments May 2008 Valley Regional Transit (VRT) and Community Planning Association of Southwest Idaho (COMPASS) hosted a second open house for the Treasure Valley High Capacity Transit Study on May 22, 2008. The study involves three interrelated projects: • Multimodal Center: A facility that brings together many transportation modes and services at a single location. • Downtown Circulator: Transit service that provides efficient connections between primary destinations in the downtown area. • I-84 Priority Corridor: A plan for high-capacity transit services along the I-84 corridor within Ada and Canyon counties. The first open house for the study was held in January 2008. The second open house provided a final opportunity for the public to comment on the location of a multimodal transportation center in downtown Boise. VRT will recommend a location in July. The multimodal center will connect various transportation modes and services. It will be the first of a network of facilities around the Valley. Construction is expected to begin in late 2009 or early 2010. At the open house, the public also reviewed and commented on two alternative alignments for a downtown circulator. Also shown were preliminary considerations for the I-84 Priority Corridor plan. VRT and COMPASS are conducting the study in partnership with Ada County, Ada County Highway District (ACHD), the City of Boise, Capital City Development Corporation (CCDC), the Downtown Business Association (DBA) and the Idaho Transportation Department (ITD). -

Livre Blanc Version Anglaise Couv + Intérieures.Indd

Working toward smart, sustainable, and optimised transport by2030 in Ile-de-France A White Paper by the Forum Métropolitain du Grand Paris mars 2018 Study carried out by: Florence Hanappe (Apur), Sara Helmi (Forum métropolitain du Grand Paris), Lydia Mykolenko (IAU-IdF), Michelle-Angélique Nicol (Apur), Patricia Pelloux (Apur), Dominique Riou (IAU-IdF), Marion Vergeylen (Forum métropolitain du Grand Paris) Publication management Dominique Alba (Apur), Fouad Awada (IAU-IdF), Sylvain Cognet (Forum métropolitain du Grand Paris) Design www.autour-des-mots.fr Printing Imprimerie Hauts de Vilaine Publication Mars 2018 Contents 2 EDITORIAL 7 PART ONE AN ONGOING TRANSFORMATION IN TRAVEL IN THE ILE-DE-FRANCE? Factors for diagnosis and forecast 9 1. Overview of travel in the Ile-de-France 19 2. What are the prospects for 2030? 43 PART TWO WORKING TOWARD SMART, SUSTAINABLE, AND OPTIMISED TRANSPORT BY 2030 IN ILE-DE-FRANCE 44 1. Proposals resulting from a citizen consultation: towards a reduction of individual car use in Ile-de-France 51 2. The elected representatives’ proposals of the Forum Métropolitain du Grand Paris for smart, sustainable, and optimised transport by 2030 in Ile-de-France 88 TABLE OF CONTENTS 90 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 92 REFERENCE DOCUMENTS O1 Editorial Joint review of future travel in the Ile-de-France region We have decided to jointly review, in a forward-looking manner, changes in travel patterns across the Ile-de-France region as we are convinced that issues concerning movement are at the heart of the challenges currently affecting metropolitan areas. Away from the political debate, and in cooperation with a group of relevant public and private stakeholders as well as residents, we have brought together over one hundred people to see what they think about travel patterns today as regards the future. -

Survey Report February 2015

El Camino Real Corridor Study Community Survey Report February 2015 www.menlopark.org/elcaminorealcorridor El Camino Real Corridor Study Community Survey Report February 2015 Prepared for City of Menlo Park by Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 2. Methodology ................................................................................................................. 3 3. Survey Results ............................................................................................................... 4 Location .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Reasons to Travel on El Camino Real ............................................................................................... 6 Transportation Modes .......................................................................................................................... 8 Opinions and Concerns ...................................................................................................................... 15 Potential Changes on El Camino Real ............................................................................................. 25 Open-Ended Questions ..................................................................................................................... -

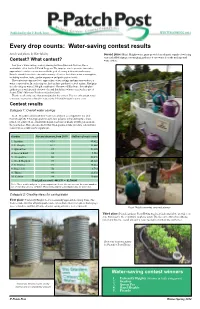

Every Drop Counts: Water-Saving Contest Results

Published by the P-Patch Trust WINTER/SPRING 2012 Every drop counts: Water-saving contest results Article and photos by Nate Moxley Second place: Hazel Heights water gurus provided an adequate supply of watering cans and added signage encouraging gardeners to use water from the underground Contest? What contest? water cistern. Last year’s water-saving contest, running between June and October, was a worthwhile effort for the P-Patch Program. The impetus was to promote innovative approaches to water conservation with the goal of saving both water and money. Results varied from site to site with a variety of factors that affect water consumption, including weather, leaks, garden expansion and participation levels. The contest encompassed two approaches: water savings and innovative ideas for water conservation. In each category, the top three gardens received a prize. First prize in each category was a $100 gift certificate to Greenwood Hardware. Second-place gardens got a variety pack of new tools, and third-place winners received a copy of Seattle Tilth’s Maritime Northwest Garden Guide. Thanks to all of the sites that participated in the contest. You not only spread water conservation awareness but also reduced the P-Patch Program’s water costs. Contest results Category 1: Overall water savings In all, 30 gardens decreased their water consumption as compared to last year. Even though the P-Patch program brought new gardens online during the contest period, we achieved an overall reduction in water use of nearly 20,000 gallons from the year before. This outcome shows that when gardeners take an active role in water conservation, results can be significant. -

ECR Corridor Study Appendices, August 3, 2015

APPENDIX A El Camino Real Corridor Study Community Survey Report El Camino Real Corridor Study A El Camino Real Corridor Study Community Survey Report February 2015 www.MenloPark-ElCamino.com El Camino Real Corridor Study Community Survey Report February 2015 Prepared for City of Menlo Park by Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 2. Methodology ................................................................................................................. 3 3. Survey Results ............................................................................................................... 4 Location .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Reasons to Travel on El Camino Real ............................................................................................... 6 Transportation Modes .......................................................................................................................... 8 Opinions and Concerns ...................................................................................................................... 15 Potential Changes on El Camino Real ............................................................................................. 25 Open-Ended -

Institutional Politics, Power Constellations, and Urban Social Sustainability: a Comparative-Historical Analysis Jason M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Institutional Politics, Power Constellations, and Urban Social Sustainability: A Comparative-Historical Analysis Jason M. Laguna Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND PUBLIC POLICY INSTITUTIONAL POLITICS, POWER CONSTELLATIONS, AND URBAN SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY: A COMPARATIVE-HISTORICAL ANALYSIS By JASON M. LAGUNA A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2014 Jason M. Laguna defended this dissertation on May 30, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Douglas Schrock Professor Directing Dissertation Andy Opel University Representative Jill Quadagno Committee Member Daniel Tope Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This is dedicated to all the friends, family members, and colleagues whose help and support made this possible. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. vi Abstract .......................................................................................................................................