21 PRINCIPLES for the 21ST CENTURY PROSECUTOR Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

Presidential Signing Statements: Will Congress Pick up the Gauntlet?

June 26, 2006 PRESIDENTIAL SIGNING STATEMENTS: WILL CONGRESS PICK UP THE GAUNTLET? David H. Remes Gerard J. Waldron ∗ Shannon A. Lang Presidential “signing statements” – formal expressions of the views of a President regarding legislation that he has just signed into law – are nearly as old as the Republic. Although previous Presidents issued signing statements, not until the Reagan Administration did they begin using such statements system- atically to influence judicial interpretation or, most recently, to declare legisla- tion non-binding on the Executive. The use of presidential signing statements to influence judicial interpreta- tion, pioneered by President Reagan, has proven ineffectual: Judges who look to legislative history at all place little weight on signing statements. The use of signing statements to deny effect to legislation, however, immediately alters the relationship between the Executive, on the one hand, and Congress and the judi- ciary, on the other. Article I of the Constitution gives Congress the last word as to whether a law will take effect, subject to judicial review, by empowering Congress to over- ride a presidential veto. When the President issues a signing statement refusing to give effect to a law, the President usurps the powers of Congress by circum- venting the Constitution’s provision for overriding presidential vetoes, and by effectively asserting unilateral power to repeal and amend legislation. Similarly, when the President denies effect to legislation because he con- siders it unconstitutional, the President displaces the judiciary as the final ex- positor of the Constitution and undermines the principle of judicial review that is crucial to our system of checks and balances. -

Traffic Tickets-**ITHACA CITY COURT ONLY

The Ithaca City Prosecutor’s Office prosecutes traffic tickets within the City of Ithaca and as part of that responsibility also makes offers to resolve tickets in writing. Please note that written dispositions can only be accommodated in cases in which the charges do not involve misdemeanors. If you are charged with any misdemeanor, including Driving While Intoxicated or Aggravated Unlicensed Operation you must appear in person in Court. The following applies to traffic tickets in the City of Ithaca that are not misdemeanors. All questions about fines, penalties and rescheduling of court dates/appearances must be addressed to the Court. If you have an upcoming Court date on a traffic ticket, only the Court can excuse your appearance. If you fail to appear in Court, the Court can suspend your driver license. If you wish to request that an upcoming appearance be rescheduled to allow time to correspond with our office, you must contact the Court directly. Contact information for the Ithaca City Court can be found here How to Request an Offer to Resolve Your Traffic Ticket Pending in Ithaca City Court Due to the large volume of the traffic caseload we only respond to email requests. Please do not use mail, fax or phone calls to solicit an offer. Please do not contact the Tompkins County District Attorney, the Tompkins County Attorney, or the Ithaca City Attorney- only the Ithaca City prosecutor. To confirm that this is the correct court, check the bottom left of your ticket- it should state that the matter is scheduled for Ithaca City Court, 118 East Clinton Street. -

Episode 55 Emily Bazelon Hello and Welcome to Episode 55 of The

Episode 55 Emily Bazelon Hello and welcome to Episode 55 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America's criminal justice system. I'm Josh Hoe, among other things, I'm formerly incarcerated a freelance writer, a criminal justice reform advocate and the author of the book, writing your own best story addiction and living hope. We'll get to my interview with Emily basil on in just a second. But first, the news: I have not told many people this but I'll share this with you here first. I've just been offered and taken a new position as the policy analyst was safe and just Michigan. This was a job I just could not say no to. I believe we can create change that affects the largest number of people here at the state level. And Michigan is and has been for a long time my home. I'm very excited to start working this month with safe and just Michigan. Nothing will change about the podcasts and they are luckily fully supportive of me continuing this work. I'm really thrilled to be starting this new adventure. And just a few months, it'll be six years since release, it took a long time to get back to a full time job. Thanks again to safe and just Michigan for giving me this opportunity and all the people and it would take an hour for me to thank everybody who has supported me over the last you know, almost six years since my release. -

Jurisprudence Diagramming Sentences by Emily Bazelon

Print jurisprudence Diagramming Sentences The Supreme Court's war on sentencing guidelines. By Emily Bazelon Posted Tuesday, Jan. 23, 2007, at 6:43 PM ET Sentencing is supposed to be the straightforward moment in a criminal trial—easy arithmetic compared to the subjective assessments of jurors and attorneys. But ever since the Supreme Court got into the sentencing biz back in 2000, sentencing has been a mess. The court struck down federal mandatory sentencing guidelines in 2005, and some state guidelines have fallen as well. And in a 6-3 decision Monday, the justices killed the California sentencing guidelines. The California case is the latest battle in a strange war that has turned natural judicial enemies into allies, set Congress against the courts, and given law professors a new life's work. Some of the justices probably have had their eye on easing the sentencing load on defendants, more and more of whom have been getting locked up for longer and longer periods. But the court can't make pro-defendant reform its explicit aim—that sort of policy decision is the legislature's job, after all, and in any case the cobbled- together majority behind the recent decisions would never hold together. So, for now, at least, the court's war on sentencing has enraged the lower courts and left the law in a shambles. These cases showcase destruction—this is what it looks like when the Supreme Court lays waste. The 2000 case that got the court started, Apprendi v. New Jersey, seemed to unveil a new constitutional right. -

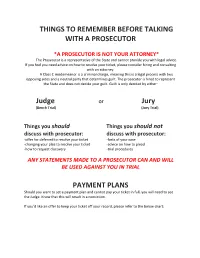

Things to Remember Before Talking with a Prosecutor

THINGS TO REMEMBER BEFORE TALKING WITH A PROSECUTOR *A PROSECUTOR IS NOT YOUR ATTORNEY* The Prosecutor is a representative of the State and cannot provide you with legal advice. If you feel you need advice on how to resolve your ticket, please consider hiring and consulting with an attorney. A Class C misdemeanor is a criminal charge, meaning this is a legal process with two opposing sides and a neutral party that determines guilt. The prosecutor is hired to represent the State and does not decide your guilt. Guilt is only decided by either: Judge or Jury (Bench Trial) (Jury Trial) Things you should Things you should not discuss with prosecutor: discuss with prosecutor: -offer for deferred to resolve your ticket -facts of your case -changing your plea to resolve your ticket -advice on how to plead -how to request discovery -trial procedures ANY STATEMENTS MADE TO A PROSECUTOR CAN AND WILL BE USED AGAINST YOU IN TRIAL PAYMENT PLANS Should you want to set a payment plan and cannot pay your ticket in full, you will need to see the Judge. Know that this will result in a conviction. If you’d like an offer to keep your ticket off your record, please refer to the below chart: How To Resolve Your Case With The Prosecutor Do you want an offer to pay for your ticket? YES NO Do you want to accept the offer No Set for trial that has been made? YES Do you need more time to save for the offer? YES NO Ask Judge for a Complete deferred continuance if you agreement and haven't had one. -

The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2001 The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Angela J., "The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny" (2001). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1397. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1397 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny AngelaJ. Davis' INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 395 I. DISCRETION, POWER, AND ABUSE ......................................................... 400 A. T-E INDF-ENDENT G E z I ETu aAD RESPO,\SE.................... -

Criminal Prosecution Guide

CAREER DEVELOPMENT OFFICE JOB GUIDE CRIMINAL PROSECUTION Description Types of Employers Prosecutors work in all levels of government–local, state, Federal—U.S. Department of Justice: and federal. Prosecutors are responsible for representing the government in criminal cases, including Post-Graduate Jobs. The DOJ hires entry-level attorneys felonies and misdemeanors. At the state and local level, only through the Attorney General’s Honors Program. this work is typically done by District Attorneys’ Offices The application period is very short, typically the month or Solicitors’ Offices. Offices of State Attorneys General of August in the year prior to your graduation year. The may also have some responsibility for criminal matters of number of attorneys hired varies from year to year, and statewide significance or for criminal appellate or post- the positions are highly competitive. conviction matters. Federal criminal matters (e.g., financial crimes, drug enforcement, and organized Paid Summer Internships. The DOJ hires a number of crime) are typically handled by a U.S. Attorney’s Office students for paid summer positions through its Summer (USAO) either exclusively or in cooperation with the Law Intern Program. These positions are open to 1Ls Criminal Division of the Office of the U.S. Attorney and 2Ls, although most successful applicants intern General. during their 2L summer. Graduating law students who will enter a judicial clerkship or a full-time graduate program may intern following graduation. The application Qualifications period is very short, typically the month of August in the year prior to the summer you would be working. Many prosecutors’ offices prefer that entry-level attorneys have coursework, summer experience and/or Unpaid Internships. -

The Prosecutor, the Term “Prosecutorial Miscon- Would Clearly Fall Within a Layperson’S Definition of Prose- Duct” Unfairly Stigmatizes That Prosecutor

The P ROSECUTOR Measuring Prosecutorial Actions An Analysis of Misconduct versus Error B Y S HAWN E. MINIHAN Rampant Prosecutorial Misconduct The New York Times, Jan. 4, 2014 The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, And The System That Protects Them The Huffington Post, Aug. 5, 2013 Misconduct by Prosecutors, Once Again The New York Times, Aug. 13, 2012 22 O CTOBER / NOVEMBER / DECEMBER / 2014 P ROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCT has become nation- in cases where such a perception is entirely unwarranted… .”11 al news. To a layperson, the term “prosecutorial miscon- The danger inherent in the court’s overbroad use of the duct” expresses “intentional wrongdoing,” or a “deliberate term “prosecutorial misconduct” is twofold. First, in cases violation of a law or standard” by a prosecutor.1 where there is an innocent mistake or poor judgment on The newspaper articles cited at left describe acts that the part of the prosecutor, the term “prosecutorial miscon- would clearly fall within a layperson’s definition of prose- duct” unfairly stigmatizes that prosecutor. A layperson may cutorial misconduct. For example, the article “Rampant assume that the prosecutor intentionally committed a Prosecutorial Misconduct” discusses United States v. Olsen, wrongdoing or deliberately violated a law or ethical stan- where federal prosecutors withheld a report that revealed dard. sloppy work on the part of the government’s forensic sci- In those cases where the prosecutor has, in fact, commit- entists, resulting in wrongful convictions.2, 3 The article ted misconduct, the term “prosecutorial misconduct” may “The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, not impose a harsh enough degree of stigmatization. -

The Roles of Litigation in American Democracy

Emory Law Journal Volume 65 Issue 6 The 2015 Pound Symposium — The "War" on the U.S. Civil Justice System (Co- Sponsored by the Pound Civil Justice Institute and Emory University School of Law) 2016 The Roles of Litigation in American Democracy Alexandra D. Lahav Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation Alexandra D. Lahav, The Roles of Litigation in American Democracy, 65 Emory L. J. 1657 (2016). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol65/iss6/12 This Articles & Essays is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAHAV GALLEYSPROOFS2 6/13/2016 1:15 PM THE ROLES OF LITIGATION IN AMERICAN DEMOCRACY ∗ Alexandra D. Lahav ABSTRACT Adjudication is usually understood as having two functions: dispute resolution and law declaration. This Article presents the process of litigation as a third, equally important function and explains how in litigation, participants perform rule of law values. Performativity in litigation operates in five ways. First, litigation allows individuals, even the most downtrodden, to obtain recognition from a governmental officer (a judge) of their claims. Second, it promotes the production of reasoned arguments about legal questions and presentation of proofs in public, subject to cross-examination and debate. Third, it promotes transparency by forcing information required to present proofs and arguments to be revealed. Fourth, it aids in the enforcement of the law in two ways: by requiring wrongdoers to answer for their conduct to the tribunal and by revealing information that is used by other actors to enforce or change existing regulatory regimes. -

1372 Swimming Guide.Indd

• • • • • • • • • • • the huskers coaching staff season review athletic administration THIS IS NEBRASKA Table of Contents Nebraska Swimming & Diving 2010-11 Media Guide ThisIsNebraska ..............................1-21 Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................1 Athletic Department Directory ...............................................................................................................................................2 Media Information and Services ...........................................................................................................................................3 This Is Nebraska ................................................................................................................................................................4-5 Sports Facilities .................................................................................................................................................................6-7 Husker Power ....................................................................................................................................................................8-9 Athletic Medicine and Nutrition ......................................................................................................................................10-11 -

November 2017 Distributor Newsletter

SeneScenes November 2017 Distributor Newsletter Get your business off on a profitable path in your first 90 days! Build up your business, and earn valuable product sets for personal use or demonstration. Now, more than ever, it pays to be a SeneGence Distributor! Message from the Founder Dear Lovely, It is amazing that we are only a couple of weeks away from 2018, and I’m sure you are just as excited as I am for the upcoming festive holiday season, with US Thanksgiving, Hanukkah and Christmas just around the corner! There is so much to be thankful for this year, but I am most thankful for my family, health, and all of you amazing Lovelies who are truly my greatest friends, and who I have the honor of watching succeed. Joni Rogers-Kante Founder & CEO Use this holiday season as the perfect time to grow your business! With sponsoring being such a critical step of your SeneGence career, I am sharing with you what I am calling “Joni's SeneScenes Law”: DISTRIBUTOR NEWSLETTER • Five – 1st line Newbies per month equals NOVEMBER 2017 | OCTOBER 2017 RECOGNITION growth. Contact Information: • Three – 1st line Newbies per month equals USA & Canada maintenance. SeneCare [email protected] How many have you sponsored since April 19651 Alter st Foothill Ranch, CA 92610 1 ? If you are sponsoring to grow, that would st Phone: (949) 860-1860 be 35 1 line Newbies to date. At what level of For updated news & productivity are you “actually doing the work”? information about SeneGence products and events: Your activity is ALWAYS seen in the results.