Dance in the Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015

2015 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Musical Director, Jake Goldbas Philanthropy in the Arts Award Legacy Award Joan and Irwin Jacobs Maria Arena Bell Presented by Christopher Ashley Presented by Jeff Koons Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Young Artist Award Herbie Hancock Lady Gaga 1 Presented by Paul Simon Presented by Klaus Biesenbach Arts Education Award Carolyn Clark Powers Alice Walton Lifetime Achievement Award Presented by Agnes Gund Sophia Loren Presented by Rob Marshall Dinner Closing Remarks Remarks by Robert L. Lynch and Abel Lopez, Chair, introduction of Carolyn Clark Powers Americans for the Arts Board of Directors and Robert L. Lynch Remarks by Carolyn Clark Powers Chair, National Arts Awards Greetings from the Board Chair and President Welcome to the 2015 National Arts Awards as Americans for the Arts celebrates its 55th year of advancing the arts and arts education throughout the nation. This year marks another milestone as it is also the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s signing of the act that created America’s two federal cultural agencies: the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Americans for the Arts was there behind the scenes at the beginning and continues as the chief advocate for federal, state, and local support for the arts including the annual NEA budget. Each year with your help we make the case for the funding that fuels creativity and innovation in communities across the United States. -

Tate Report 2010-11: List of Tate Archive Accessions

Tate Report 10–11 Tate Tate Report 10 –11 It is the exceptional generosity and vision If you would like to find out more about Published 2011 by of individuals, corporations and numerous how you can become involved and help order of the Tate Trustees by Tate private foundations and public-sector bodies support Tate, please contact us at: Publishing, a division of Tate Enterprises that has helped Tate to become what it is Ltd, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG today and enabled us to: Development Office www.tate.org.uk/publishing Tate Offer innovative, landmark exhibitions Millbank © Tate 2011 and Collection displays London SW1P 4RG ISBN 978-1-84976-044-7 Tel +44 (0)20 7887 4900 Develop imaginative learning programmes Fax +44 (0)20 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Strengthen and extend the range of our American Patrons of Tate Collection, and conserve and care for it Every effort has been made to locate the 520 West 27 Street Unit 404 copyright owners of images included in New York, NY 10001 Advance innovative scholarship and research this report and to meet their requirements. USA The publishers apologise for any Tel +1 212 643 2818 Ensure that our galleries are accessible and omissions, which they will be pleased Fax +1 212 643 1001 continue to meet the needs of our visitors. to rectify at the earliest opportunity. Or visit us at Produced, written and edited by www.tate.org.uk/support Helen Beeckmans, Oliver Bennett, Lee Cheshire, Ruth Findlay, Masina Frost, Tate Directors serving in 2010-11 Celeste -

The Creative Arts at Brandeis by Karen Klein

The Creative Arts at Brandeis by Karen Klein The University’s early, ardent, and exceptional support for the arts may be showing signs of a renaissance. If you drive onto the Brandeis campus humanities, social sciences, and in late March or April, you will see natural sciences. Brandeis’s brightly colored banners along the “significant deviation” was to add a peripheral road. Their white squiggle fourth area to its core: music, theater denotes the Creative Arts Festival, 10 arts, fine arts. The School of Music, days full of drama, comedy, dance, art Drama, and Fine Arts opened in 1949 exhibitions, poetry readings, and with one teacher, Erwin Bodky, a music, organized with blessed musician and an authority on Bach’s persistence by Elaine Wong, associate keyboard works. By 1952, several Leonard dean of arts and sciences. Most of the pioneering faculty had joined the Leonard Bernstein, 1952 work is by students, but some staff and School of Creative Arts, as it came to faculty also participate, as well as a be known, and concentrations were few outside artists: an expert in East available in the three areas. All Asian calligraphy running a workshop, students, however, were required to for example, or performances from take some creative arts and according MOMIX, a professional dance troupe. to Sachar, “we were one of the few The Wish-Water Cycle, brainchild of colleges to include this area in its Robin Dash, visiting scholar/artist in requirements. In most established the Humanities Interdisciplinary universities, the arts were still Program, transforms the Volen Plaza struggling to attain respectability as an into a rainbow of participants’ wishes academic discipline.” floating in bowls of colored water: “I wish poverty was a thing of the past,” But at newly founded Brandeis, the “wooden spoons and close friends for arts were central to its mission. -

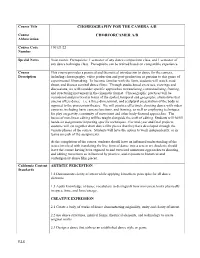

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

The One Who Knocks: the Hero As Villain in Contemporary Televised Narra�Ves

The One Who Knocks: The Hero as Villain in Contemporary Televised Narra�ves Maria João Brasão Marques The One Who Knocks: The Hero as Villain in Contemporary Televised Narratives Maria João Brasão Marques 3 Editora online em acesso aberto ESTC edições, criada em dezembro de 2016, é a editora académica da Escola Superior de Teatro e Cinema, destinada a publicar, a convite, textos e outros trabalhos produzidos, em primeiro lugar, pelos seus professores, investigadores e alunos, mas também por autores próximos da Escola. A editora promove a edição online de ensaio e ficção. Editor responsável: João Maria Mendes Conselho Editorial: Álvaro Correia, David Antunes, Eugénia Vasques, José Bogalheiro, Luca Aprea, Manuela Viegas, Marta Mendes e Vítor Gonçalves Articulação com as edições da Biblioteca da ESTC: Luísa Marques, bibliotecária. Editor executivo: Roger Madureira, Gabinete de Comunicação e Imagem da ESTC. Secretariado executivo: Rute Fialho. Avenida Marquês de Pombal, 22-B 2700-571 Amadora PORTUGAL Tel.: (+351) 214 989 400 Telm.: (+351) 965 912 370 · (+351) 910 510 304 Fax: (+351) 214 989 401 Endereço eletrónico: [email protected] Título: The One Who Knocks: The Hero as Villain in Contemporary Televised Narratives Autor: Maria João Brasão Marques Série: Ensaio ISBN: 978-972-9370-27-4 Citações do texto: MARQUES, Maria João Brasão (2016), The one who knocks: the hero as villain in contemporary televised narratives, Amadora, ESTC Edições, disponível em <www.estc.ipl.pt>. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International License. https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/CC_Affiliate_Network O conteúdo desta obra está protegido por Lei. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, October 14, 2020

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, October 14, 2020 MOCA FORMS ENVIRONMENTAL COUNCIL A FIRST FOR A MAJOR U.S. ART MUSEUM The Aileen Getty Plaza at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. LOS ANGELES—The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) announces the creation of an Environmental Council, the first for a major art museum in the United States. The Council is focused on climate, conservation, and environmental justice in furtherance of the museum’s mission. In development since Klaus Biesenbach became the Director of MOCA in 2018, the museum will unfold important initiatives made possible by the Council within the first year, including financial commitments and expertise to work toward institution-wide carbon negativity, carbon- free energy, environmentally-focused museum quality exhibitions, educational programming, related artist support, and reductions in emissions and consumption. MOCA plans to publicly share the Council’s efforts and progress as a platform for public dialogue and engagement on this urgent topic. MOCA Environmental Council Founders and Co-Chairs are David Johnson and Haley Mellin. Founding Council members are Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Aileen Getty, Agnes Gund, Sheikha Al Mayassa Bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani and Brian Sheth. Expert advisors to the Council include Illina Frankiv, Dan Hammer, Lisa P. Jackson, Lucas Joppa, Jen Morris, Calla Rose Ostrander and Enrique Ortiz. MOCA Executive Director, Klaus Biesenbach, and MOCA Deputy Director, Advancement, Samuel Vasquez will be ex-officio members of the Council and assure continuity and communication between the Council’s priorities and the museum’s activities and operations. The Council will support artists working on critical environmental issues by financially supporting meaningful exhibition and educational programming. -

VISITOR FIGURES 2015 the Grand Totals: Exhibition and Museum Attendance Numbers Worldwide

SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide VISITOR FIGURES 2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide THE DIRECTORS THE ARTISTS They tell us about their unlikely Six artists on the exhibitions blockbusters and surprise flops that made their careers U. ALLEMANDI & CO. PUBLISHING LTD. EVENTS, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS MONTHLY. EST. 1983, VOL. XXV, NO. 278, APRIL 2016 II THE ART NEWSPAPER SPECIAL REPORT Number 278, April 2016 SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES 2015 Exhibition & museum attendance survey JEFF KOONS is the toast of Paris and Bilbao But Taipei tops our annual attendance survey, with a show of works by the 20th-century artist Chen Cheng-po atisse cut-outs in New attracted more than 9,500 visitors a day to Rio de York, Monet land- Janeiro’s Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil. Despite scapes in Tokyo and Brazil’s economic crisis, the deep-pocketed bank’s Picasso paintings in foundation continued to organise high-profile, free Rio de Janeiro were exhibitions. Works by Kandinsky from the State overshadowed in 2015 Russian Museum in St Petersburg also packed the by attendance at nine punters in Brasilia, Rio, São Paulo and Belo Hori- shows organised by the zonte; more than one million people saw the show National Palace Museum in Taipei. The eclectic on its Brazilian tour. Mgroup of exhibitions topped our annual survey Bernard Arnault’s new Fondation Louis Vuitton despite the fact that the Taiwanese national muse- used its ample resources to organise a loan show um’s total attendance fell slightly during its 90th that any public museum would envy. -

Clifford the Big Red Dog Goes on Tour! MAY 2018 See Page 31 for Details

Clifford The Big Red Dog goes on tour! MAY 2018 See page 31 for details NOVA Wonders Airs 8pm Wednesdays Journey to the frontiers of science, where researchers are tackling some of the biggest questions about life and the cosmos in this six-part mini-series. See story, p. 2 MONTANAPBS PROGRAM GUIDE MontanaPBS Guide On the Cover MAY 2018 · VOL. 31 · NO. 11 COPYRIGHT © 2018 MONTANAPBS, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MEMBERSHIP 1-866-832-0829 SHOP 1-800-406-6383 EMAIL [email protected] WEBSITE www.montanapbs.org ONLINE VIDEO PLAYER watch.montanapbs.org The Guide to MontanaPBS is printed monthly by the Bozeman Daily Chronicle for MontanaPBS and the Friends of MontanaPBS, Inc., a nonprofit corporation (501(c)3) P.O. Box 10715, Bozeman, MT 59719-0715. The publication is sent to contributors to MontanaPBS. Basic annual membership is $35. Nonprofit periodical postage paid at Bozeman, MT. PLEASE SEND CHANGE OF ADDRESS INFORMATION TO: SHUTTERSTOCK OF COURTESY MontanaPBS Membership, P.O. Box 173345, Bozeman, MT 59717 KUSM-TV Channel Guide P.O. Box 173340 · Montana State University Mont. Capitol Coverage Bozeman, MT 59717–3340 MontanaPBS World OFFICE (406) 994-3437 FAX (406) 994-6545 MontanaPBS Create E-MAIL [email protected] MontanaPBS Kids BOZEMAN STAFF MontanaPBS HD INTERIM GENERAL MANAGER Aaron Pruitt INTERIM DIRECTOR OF CONTENT/ Billings 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 CHIEF OPERATOR Paul Heitt-Rennie Butte/Bozeman 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 SENIOR DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT Crystal Beaty MEMBERSHIP/EVENTS MANAGER Erika Matsuda Great Falls 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 DEVELOPMENT ASST. -

Embodied History in Ralph Lemon's Come Home Charley Patton

“My Body as a Memory Map:” Embodied History in Ralph Lemon’s Come Home Charley Patton Doria E. Charlson I begin with the body, no way around it. The body as place, memory, culture, and as a vehicle for a cultural language. And so of course I’m in a current state of the wonderment of the politics of form. That I can feel both emotional outrageousness with my body as a memory map, an emotional geography of a particular American identity...1 Choreographer and visual artist Ralph Lemon’s interventions into the themes of race, art, identity, and history are a hallmark of his almost four-decade- long career as a performer and art-maker. Lemon, a native of Minnesota, was a student of dance and theater who began his career in New York, performing with multimedia artists such as Meredith Monk before starting his own company in 1985. Lemon’s artistic style is intermedial and draws on the visual, aural, musical, and physical to explore themes related to his personal history. Geography, Lemon’s trilogy of dance and intermedial artistic pieces, spans ten years of global, investigative creative processes aimed at unearthing the relationships among—and the possible representations of—race, art, identity, and history. Part one of the trilogy, also called Geography, premiered in 1997 as a dance piece and was inspired by Lemon’s journey to Africa, in particular to Côte d'Ivoire and Guinea, where Lemon sought to more deeply understand his identity as an African-American male artist. He subseQuently published a collection of writings, drawings, and notes which he had amassed during his research and travel in Africa under the title Geography: Art, Race, Exile. -

Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier BABETTE MANGOLTE

Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier BABETTE MANGOLTE Booklet #Mangolte 18/12 2016 – 12/2 2017 www.kunsthallewien.at Babette Mangolte In response to which films have influenced her the most, she cites I = EYE Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) and Michael Snow’s Babette Mangolte (*1941) is an Wavelength (1967): “These two films icon of international experimental literally changed my life. The first cinema. From the beginning, her one made me decide to become a early interests focused on the cinematographer, and the desire documentation of the New York art, to see the second one led me to dance, and theatre scene of the New York, where I settled down and 1970s, and above all, on performance eventually made my films.” 1 art. The adaptation of dance and choreography for the media of Babette Mangolte was the film and photography – and the cinematographer for Chantal concomitant question regarding the Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975) and changes this transfer has on an event News From Home (1977), and also for based on the live experience – play Yvonne Rainer’s Lives of Performers a central role in her work. (1972) and Film about a Woman Who... (1974). In 1975, she completed her I = EYE not only presents an array first film What Maisie Knew, which of Mangolte’s film and photo works won the “Prix de la Lumière” at the from the 1970s, but also more Toulon Film Festival in the same year. recent projects, which explore the Subsequently, other significant films historicisation of performance from her filmography include The art, and the differences between Camera: Je or La Camera: I (1977), perceptions of contemporaneity The Cold Eye (My Darling, Be Careful) past and present, as well as (1980), The Sky on Location (1982), conceptualizations of time. -

(The Efflorescence Of) Walter, an Exhibition by Ralph Lemon

Press Contact: Rachael Dorsey tel: 212 255-5793 ext. 14 fax: 212 645-4258 [email protected] For Immediate Release The Kitchen presents (The efflorescence of) Walter, an exhibition by Ralph Lemon New York, NY, April 17, 2007 – The Kitchen is pleased to present the first New York solo exhibition by choreographer, dancer, and visual artist Ralph Lemon. Titled (The efflorescence of) Walter, the show includes a body of work focused on the American South, featuring works-on-paper, a multiple-channel video installation, and other sculptural elements that explore history, memory, and memorialization. There will be an opening reception for the exhibition at The Kitchen (512 West 19th Street) on Friday, May 11 from 6- 8pm. Curated by Claire Tancons and Anthony Allen, the exhibition will be on view from May 11 – June 23, 2007. The Kitchen’s gallery hours are Tuesday-Friday, 12 to 6pm and Saturday, 11am to 6pm. Admission is Free. (The efflorescence of) Walter revolves around Lemon's collaborative relationship with Walter Carter, an African American man who has lived for almost a century in Yazoo City, Mississippi. Since 2002, Lemon and Carter have met twice a year and created a “collaborative meta-theater” in which actions scripted by Lemon are translated and transformed through Carter’s performance and improvisations. The exhibition weaves together videos of Walter’s actions with paintings, drawings and photographs by Lemon. Bringing together figures as varied as writer James Baldwin, artist Joseph Beuys, and Br’er Rabbit, a central character of African American folktales; as well as historical events from the Civil Rights era and cultural artifacts of the American South, this complex engagement with history, myth, and daily human existence explores how past, present, and future co-exist and at times collide. -

Bill T. Jones / Arnie Zane Dance Company

FALL 2018 DANCE SEASON B R AVO Bill T. Jones/ Arnie Zane Company OCTOBER 27, 2018 BALLETMET The Nutcracker NOVEMBER 24-25, 2018 Too Hot to Handel DECEMBER 1, 2018 The 2018–2019 Dance Season is made possible by the Lear Corporation ENGAGED IN THE ARTS. COMMITTED TO CULTURE. IMPACTING OUR COMMUNITY. The Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan proudly supports the Michigan Opera Theatre as part of our mission to assist organizations creating a lasting, positive impact on our region. CFSEM.org 313-961-6675 Fall 2018 BRAVO Contents Dance Season ON STAGE The Official Magazine of Michigan Opera Theatre FEATURE STORY: ‘Tis the Season for Holiday Performances ......... 6 Profiles from the Pit: All About that Bass ............................................... 7 Erica Hobbs, Editor Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company ............................................................ 8 Jocelyn Aptowitz, Contributor BalletMet’s The Nutcracker ........................................................................14 Publisher: Too Hot To Handel .........................................................................................20 Echo Publications, Inc. Royal Oak, Michigan www.echopublications.com MICHIGAN OPERA THEATRE Tom Putters, President Boards of Directors and Trustees .............................................................. 4 Physicians’ services provided by Welcome ............................................................................................................. 5 Henry Ford Medical Center. MOTCC: A Winter Fantasy ..........................................................................19