Ibrahim-Mastersreport-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

SYNCHRONICITY and VISUAL MUSIC a Senior Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Business, Entrepreneurship An

SYNCHRONICITY AND VISUAL MUSIC A Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Music Business, Entrepreneurship and Technology The University of the Arts In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE By Zarek Rubin May 9, 2019 Rubin 1 Music and visuals have an integral relationship that cannot be broken. The relationship is evident when album artwork, album packaging, and music videos still exist. For most individuals, music videos and album artwork fulfill the listener’s imagination, concept, and perception of a finished music product. For other individuals, the visuals may distract or ruin the imagination of the listener. Listening to music on an album is like reading a novel. The audience builds their own imagination from the work, but any visuals such as the novel cover to media adaptations can ruin the preexisted vision the audience possesses. Despite the audience’s imagination, music can be visualized in different forms of visual media and it can fulfill the listener’s imagination in a different context. Listeners get introduced to new music in film, television, advertisement, film trailers, and video games. Content creators on YouTube introduce a song or playlist with visuals they edit themselves. The content creators credit the music artist in the description of the video and music fans listen to the music through the links provided. The YouTube channel, “ChilledCow”, synchronizes Lo-Fi hip hop music to a gif of a girl studying from the 2012 anime film, Wolf Children. These videos are a new form of radio on the internet. -

At the Jericho Tavern on Saturday NIGHTSHIFT PHOTOGRAPHER 10Th November

[email protected] nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 207 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2012 Alphabet Backwards photo: Jenny Hardcore photo: Jenny Hardcore Go pop! NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net DAMO SUZUKI is set to headline The album is available to download this year’s Audioscope festival. The for a bargain £5 at legendary former Can singer will www.musicforagoodhome.com. play a set with The ODC Drumline at the Jericho Tavern on Saturday NIGHTSHIFT PHOTOGRAPHER 10th November. Damo first headlined Johnny Moto officially launches his Audioscope back in 2003 and has new photo exhibition at the Jericho SUPERGRASS will receive a special Performing Rights Society Heritage made occasional return visits to Tavern with a gig at the same venue Award this month. The band, who formed in 1993, will receive the award Oxford since, including a spectacular this month. at The Jericho Tavern, the legendary venue where they signed their record set at Truck Festival in 2009 backed Johnny has been taking photos of deal back in 1994 before going on to release six studio albums and a string by an all-star cast of Oxfordshire local gigs for over 25 years now, of hit singles, helping to put the Oxford music scene on the world map in the musicians. capturing many of the best local and process. Joining Suzuki at Audioscope, which touring acts to pass through the city Gaz Coombes, Mick Quinn and Danny Goffey will receive the award at the raises money for homeless charity in that time and a remains a familiar Tavern on October 3rd. -

Afrofuturism, Critical Race Theory, and Policing in the Year 2044 I

Brooklyn Law School Legal Studies Research Papers Accepted Paper Series Research Paper No. 586 February 2019 Afrofuturism, Critical Race Theory, and Policing in the Year 2044 I. Bennett Capers This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract=3331295 CAPERS-LIVE(DO NOT DELETE) 2/7/19 7:58 PM ARTICLES AFROFUTURISM, CRITICAL RACE THEORY, AND POLICING IN THE YEAR 2044 I. BENNETT CAPERS* In 2044, the United States is projected to become a “majority- minority” country, with people of color making up more than half of the population. And yet in the public imagination— from Robocop to Minority Report, from Star Trek to Star Wars, from A Clockwork Orange to 1984 to Brave New World—the future is usually envisioned as majority white. What might the future look like in year 2044, when people of color make up the majority in terms of numbers, or in the ensuing years, when they also wield the majority of political and economic power? And specifically, what might policing look like? This Article attempts to answer these questions by examining how artists, cybertheorists, and speculative scholars of color— Afrofuturists and Critical Race Theorists—have imagined the future. What can we learn from Afrofuturism, the term given to “speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns [in the context of] techno culture?” And what can we learn from Critical Race Theory and its “father” Derrick Bell, who famously wrote of space explorers to examine issues of race and law? What do they imagine policing to be, and what can we imagine policing to be in a brown and black world? ∗ Copyright © 2019 by I. -

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) FEB CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 13 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2021 $NOT HS 16, 19 BEYONCE STX 14; WM 7 TASHA COBBS LEONARD GA 4, 11, 12, 14; ZACARIAS FERREIRA TSA 17 HOTBOII HS 20 -L- GS 12 21 SAVAGE B200 53; RBA 29; RLP 24; H100 JUSTIN BIEBER B200 187; RBL 24; A40 3, 12, LA FIERA DE OJINAGA RMS 33 STEPHEN HOUGH CL 6 LABRINTH STX 22 100; RBH 36, 38; RP 22 23; AC 7, 11; DA 20, 36; H100 9, 12, 28, 85; COCHREN & CO. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Quarterly Magazine

FLORIDA- CARIBBEAN Caribbean Cruising CRUISE THE FLORIDA-CARIBBEAN CRUISE ASSOCIATION MAGAZINE ASSOCIATION Third Quarter 2007 EXECUTIVE FEATURES COMMITTEE FCCAMicky Chairman, Arison Chairman & CEO 9 The 2007 FCCA Caribbean Cruise Conference and Trade Show. Carnival Corporation Join us in Cozumel, Mexico to foster new relationships. PresidentThomas M. McAlpin 12 A Look Inside Playa Mia Grand Beach Park. Disney Cruise Line 18 What Destinations Can Learn From Disney Cruise Line. PresidentRichard &E. CEO Sasso MSC Cruises (USA) Inc. By Tom McAlpin, President - Disney Cruise Line. PresidentColin V eitch& CEO 24 Port Everglades Expands for the Future. Norwegian Cruise Line 28 Tours - Thinking Outside the Box. VStephenice President, A. Nielsen By Darius Mehta, Director Land Programs - Regent Seven Caribbean & Atlantic Shore Operations Seas Cruises. Princess Cruises/Cunard Line 30 Cozumel - An Island of Cultural Treasures. PrAdamesident Goldstein Royal Caribbean International RCCL’s Patrick Schneider, Director of Shore Excursions Shares FCCA STAff 34 RCCL’s Patrick Schneider, Director of Shore Excursions Shares His Goals With Us. GraphicsOmari BrCoordinatoreakenridge 36 Cruise Control - Managing the Cruise Industry. Director,Terri Cannici Special Events By Vincent Vanderpool-Wallace, Secretary General & CEO, Caribbean Tourism Organization. VAdamice President Ceserano 40 NCL Welcomes New Billion Dollar Shareholder to Freestyle ExecutiveJessica LalamaAssistant Cruising and the Industry’s Youngest Fleet. Star Cruises and Apollo Team Up to Boost -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

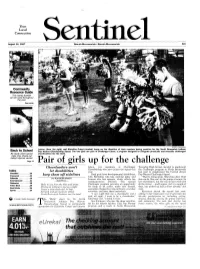

Pair of Girls up for the Challenge

Your Local Connection August 16, 2007 North Brunswick • South Brunswick 500 Community Resource Guide This handy booklet can be used throughout the year See inside SCOTT FRIEDMAN Lauren Libou (far right) and Khristina Criqui (seated) focus on the direction of their coaches during practice for the North Brunswick Indians Back to School Pop Warner Cheerleading Squad. The two girls are part of Challenger Cheer, a program designed to integrate physically and mentally challenged Be ready when school cheerleaders into the team. bells ring. Check out today's special section Page 13 Pair of girls up for the challenge Cheerleaders won't Libou, two members of Challenger Township High School, decided to implement Cheerleading who have joined the squad this the Challenger program in North Brunswick Index let disabilities year. last year to complement the Central Jersey Classified 39 keep them off sidelines Both girls have developmental disabilities, Pop Warner Challenger Squad. Crossword .33 with Khristina who has cerebral palsy and "They're doing great. Khristina does what Editorials 10 BY JENNIFER AMATO Lauren who has apraxia, which affects her she can do. She can't do the jumps of course [in Entertainment 31 Staff Writer communication abilities. The special her wheelchair], but she can do the twirls and Obituaries 28 Challenger program provides an opportunity do the moves ... and Lauren, just in a couple of Police Beat 29 Hello to you from the blue and white. I'll stop at nothing to put up a fight. for them to be active, make new friends, days, has picked up half a cheer already," she Real Estate 35 assimilate themselves into ordinary, everyday said. -

The Cinematic Worlds of Michael Jackson

MA 330.004 / MA430.005 /AMST 341.002 Fall 2016 Revised: 10-7-16 The Cinematic Worlds of Michael Jackson Course Description: From his early years as a child star on the Chitlin’ Circuit and at Motown Records, through the concert rehearsal documentary This is It (released shortly after his death in 2009), Michael Jackson left a rich legacy of recorded music, televised performances, and short films (a description he preferred to “music video”). In this course we’ll look at Jackson’s artistic work as key to his vast influence on popular culture over the past 50 years. While we will emphasize the short films he starred in (of which Thriller is perhaps the most famous), we will also listen to his music, view his concert footage and TV appearances (including some rare interviews) and explore the few feature films in which he appeared as an actor/singer/dancer (The Wiz, Moonwalker). We’ll read from a growing body of scholarly writing on Jackson’s cultural significance, noting the ways he drew from a very diverse performance and musical traditions—including minstrelsy, the work of dance/choreography pioneers like Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, and soul/funk legends like James Brown and Jackie Wilson—to craft a style uniquely his own. Crucially, we will ask how Jackson’s shifting public persona destabilize categories of gender, sexuality, and race----in a manner that was very different from his contemporaries: notably, the recently-deceased David Bowie and Prince. Elevated to superstardom and then made an object of the voracious cultural appetite for scandal, Michael Jackson is now increasingly regarded as a singularly influential figure in the history of popular music and culture. -

TREE of CLUES: a Packet for Popheads

TREE OF CLUES: a packet for popheads Written by Kevin Kodama 1. In one song by this artist, a background clicking noise slows down as she sings “I found another way / To caress my day”. One of this artist’s videos is a single shot of her as both a giant goddess and tiny dancers that slowly zooms out. A track by this artist that she described as “a medieval march through the destruction of a relationship” laments “I never thought that you would be the one to tie me down”. This artist asks “Why don’t I do it for you” in a video that showcases her pole-dancing skills, and she explained a part of her name as “a selection of letters that sounded... masculine and strong”. For ten points, name this artist who released “Cellophane” for her 2019 album MAGDALENE. ANSWER: FKA twigs (accept Taliah Debrett Barnett) 2. This song’s heavily ad-libbed bridge includes the James Brown-inspired lyric “Good God! I can’t help it!”. In the music video for this song, the artist crawls on the ground sporting white polka dotted lipstick. This song begins with a series of tongue clicking and a breathy “yeah” along with some funky guitars. The video for this song uses pink, purple, and blue lighting in a scene where the artist runs between a male flirt and Tessa Thompson. This song’s artist describes herself as “an emotional sexual bender”, which is a nod to her pansexuality. For ten points, name this top r/popheads track of 2018, a Janelle Monae song that was the lead single for the album Dirty Computer. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research.