LLOYD HAMILTON PETERS Phd Thesis 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Events Plan Ahead with Our Big Listings Guide

JAN 20 - FEB 3 2016 200+ Events www.getintonewcastle.co.uk Plan ahead with our big listings guide NEW Big LOOK! eat It’s back! Eat for just £10pp and INSIDE £15pp during the biggest-ever NE1 Newcastle Restaurant Week Reeves and Mortimer Heading for a big night out Rambert Dance Co They’re the greatest dancers... Hit the gym Twinkle toes Go on, you know you want to! Strictly Come Dancing Live Tour hits Newcastle FREE NE1 magazine is brought to you by NE1 Ltd, the company which champions all that’s great about Newcastle city centre Restaurant Week 12Come dining NE1’s Newcastle Restaurant Contents Week is back January 18-24 18th-24th January What’s #NE1RestaurantWeek on in NE1 04 Going out? It’s all here - Arenacross, Burns Night, an Eagle about town and much more 11 New you Step away from the sofa people - this is your guide to getting in shape in NE1 14 Music Bowling for Soup, Alexander Armstrong and the mighty Temple of Rock 16 Keeeeep dancing Strictly Come Dancing hits town 20 Shooting Stars One Vic and Bob’s 25 years of silliness Week, 22 Listings 80+ Restaurants, Your go-to guide to NE1 goings-on Bonbar pp* or 15 10 £ ©Offstone Publishing 2016. All rights Publishers: Jane Pikett, Gary Ramsay £ reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced without the written permission Writers: Dean Bailey, Claire Dupree of the publisher. All information contained (listings editor) in this magazine is as far as we are aware, Designers: Stuart Blackie If you wish to submit a listing for inclusion correct at the time of going to press. -

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction Tuesday 19th February 2019 at 10.00 Viewing: For enquiries relating to the auction Monday 18th February 2019 10:00 - 16:00 please contact: 09:00 morning of auction Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One 81 Greenham Business Park NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment Music www.specialauctionservices.com As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indications of the provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. ORDER OF AUCTION Music Hall & other Disc Records 1-68 Cylinder Records 69-108 Phonographs & Gramophones 109-149 Technical Apparatus 150-155 Musical Boxes 156-171 Jazz/ other 78s 172-184 Vinyl Records 185-549 Reel to Reel Tapes 550-556 CDs/ CD Box Sets 557-604 DVDs 605-612 Music Memorabilia 613-658 Music Posters 659-666 Film & Entertainment Memorabilia Including items from the Estate of John Inman 667-718 Film Posters 719-743 Musical Instruments 744-759 Hi-Fi 760-786 2 www.specialauctionservices.com MUSIC HALL & OTHER DISC RECORDS 18. Music hall and similar records, 10 inch, 67, by Geo Robey (G & T 2-2721 & 18 1. -

Media Coverage June 2014 – July 2014

Media Coverage June 2014 – July 2014 TeenTech Media Coverage June 2014 - July 2014 Opportunities Date Media Outlet Headline Circulation to See 25 June 2014 The Telegraph Online Tech award challenges teens to make life 64,191,797 192,575,391 'better, simpler or easier' 25 June 2014 sNEWSi Online Tech award challenges teens to make life N/A N/A 'better,simpler or easier' 26 June 2014 Daily Mail Online From a pen that spots spelling mistakes to 11,241,257 33,723,771 home-grown CLOTHES: Teens design range of futuristic gadgets for cars and houses 26 June 2014 4iNews (UK Edition) Online A spelling pen and veg-counting wristband N/A N/A are among teens' inventions 26 June 2014 News Locker Online Teens design range of futuristic gadgets for N/A N/A cars and houses 26 June 2014 News Reality Online From a pen that spots spelling mistakes to N/A N/A home-grown CLOTHES: Teens design range of futuristic gadgets for cars and houses 26 June 2014 Newscloud Online From a pen that spots spelling mistakes to N/A N/A home-grown CLOTHES: Teens design range of futuristic gadgets for cars and houses 26 June 2014 Top News Today Online From a pen that spots spelling mistakes to N/A N/A home-grown CLOTHES: Teens design range of futuristic gadgets for cars and houses TeenTech Media Coverage June 2014 - July 2014 Opportunities Date Media Outlet Headline Circulation to See 26 June 2014 vnc (viral news chart) Online From a pen that spots spelling mistakes to N/A N/A home-grown CLOTHES: Teens design range of futuristic gadgets for cars and houses 27 June 2014 Comms -

Old Jack's Boat

OLD JACK’S BOAT / TX01: THE PEARL EARRING / POST PRODUCTION SCRIPT Post Production Script Old Jack’s Boat – TX01: The Pearl Earring By Tracey Hammett Characters appearing in this script: Jack Miss Bowline-Hitch Emily Scuttlebutt Ernie Starboard Pearl (Shelly Perriwinkle) MUSIC 1 10:00:00-0138 SCENE 1: TITLES/JACK’S INTRO/SONG IN THE TITLES OLD JACK’S BOAT TAKES A COURSE ALONG AN ANIMATED MAP. WEAVING IN AND OUT OF THE VARIOUS SITUATIONS AND CHARACTERS FROM THE STORIES. AT THE END OF THE ANIMATED JOURNEY, OLD JACK’S BOAT AT 20” RISES UP TO FORM THE ‘OLD JACKS’ BOAT LOGO. A FAST ZOOM IN TO THE BOAT’S PORTHOLE FINDS JACK EXITING HIS HOUSE ALONG WITH SALTY. 10:00:21 SCENE 2: OLD JACK’S COTTAGE JACK PULLS THE DOOR BEHIND HIM AND POINTS TO CAMERA JACK: Good day to you! JACK WINKS AND THEN STRIDES OFF DOWN THE ROAD WITH SALTY. THE MUSIC SEQUES INTO “JACK’S SONG” 10:00:28 SCENE 3: EXT VILLAGE SEES JACK WALKING THROUGH THE VILLAGE MEETING HIS VARIOUS FRIENDS. HIS FRIENDS ARE EACH ON THE WAY TO WORK. THERE IS A GENERAL AIR OF BUSY ACTIVITY AS EACH OF THE CHARACTERS GETS READY FOR 1 OLD JACK’S BOAT / TX01: THE PEARL EARRING / SHOOTING SCRIPT THEIR DAY. OLD JACK WAVES TO THEM AND THEY WAVE BACK. THE LYRICS OF THE SONG THAT JACK IS SINGING GIVE A BRIEF, FOND DESCRIPTION OF EACH OF THE CHARACTERS. AT THE END OF THIS INTRODUCTION SEQ THERE IS AN ANIMATED GRAPHIC OF A FISH THAT WIPES THROUGH FRAME. -

Young, Gifted and Punk: My Mad Days with Rik Mayall June 18, 2014 6.03Am BST

Young, gifted and punk: my mad days with Rik Mayall June 18, 2014 6.03am BST The untimely death of me old mucker Rik Mayall last week has prompted a plethora of obituaries in the press and on television and radio. However, as someone who “nearly” grew up with Rik at Manchester University in the mid- 1970s (we never quite made the leap to post-adolescence) his premature death has been a devastating personal blow – as it has, I’m sure, to all those who knew him. As the youngest of the 1975 intake – Rik was only 56 years old when he died – his passing not only uncomfortably reminds us all of our own mortality but has invoked the glorious memories of an age of creative experiment and glorious mayhem. As an undergraduate studying Drama at Manchester University, I first met Rik when both housed in the Manchester University Hall’s of Residence at Owen’s Park, Fallowfield. What united us from the off was our love of the absurd, the irreverent and the cheap burgers from the so-called Armpit – the nearby Canadian Charcoal Pit take-away. Also we both had a penchant for pulling faces, putting on silly voices and like many of our generation, quoting large sections of Monty Python sketches, which were seen as de rigeur for “coolness” in the mid- 1970s. He was a fascinating life-force, not least because he could stick the top of his ear into the hole. The living was easy at that time with generous student grants to ease the squalor of student life – or rather to propagate it. -

Cteea/S5/20/25/A Culture, Tourism, Europe And

CTEEA/S5/20/25/A CULTURE, TOURISM, EUROPE AND EXTERNAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE AGENDA 25th Meeting, 2020 (Session 5) Thursday 29 October 2020 The Committee will meet at 9.00 am in a virtual meeting and will be broadcast on www.scottishparliament.tv. 1. Decision on taking business in private: The Committee will decide whether to take item 6 in private. 2. Subordinate legislation: The Committee will take evidence on the Census (Scotland) Amendment Order 2020 [draft] from— Fiona Hyslop, Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Fair Work and Culture, and Jamie MacQueen, Lawyer, Scottish Government; Pete Whitehouse, Director of Statistical Services, National Records of Scotland. 3. Subordinate legislation: Fiona Hyslop (Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Fair Work and Culture) to move— S5M-22767—That the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee recommends that the Census (Scotland) Amendment Order 2020 [draft] be approved. 4. BBC Annual Report and Accounts: The Committee will take evidence from— Steve Carson, Director, BBC Scotland; Glyn Isherwood, Chief Financial Officer, BBC. 5. Consideration of evidence (in private): The Committee will consider the evidence heard earlier in the meeting. 6. Pre-Budget Scrutiny: The Committee will consider correspondence. CTEEA/S5/20/25/A Stephen Herbert Clerk to the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee Room T3.40 The Scottish Parliament Edinburgh Tel: 0131 348 5234 Email: [email protected] CTEEA/S5/20/25/A The papers for this meeting are as follows— Agenda item 2 Note by the Clerk CTEEA/S5/20/25/1 Agenda item 4 Note by the Clerk CTEEA/S5/20/25/2 PRIVATE PAPER CTEEA/S5/20/25/3 (P) Agenda item 6 PRIVATE PAPER CTEEA/S5/20/25/4 (P) CTEEA/S5/20/25/1 Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee 25th Meeting, 2020 (Session 5), Thursday 29 October 2020 Subordinate Legislation Note by the Clerk Overview of instrument 1. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

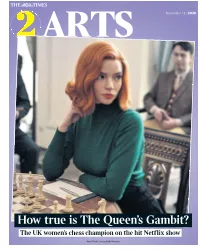

How True Is the Queen's Gambit?

ARTS November 13 | 2020 How true is The Queen’s Gambit? The UK women’s chess champion on the hit Netflix show Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon 2 1GT Friday November 13 2020 | the times times2 Caitlin 6 4 DOWN UP Moran Demi Lovato Quote of It’s hard being a former Disney child the Weekk star. Eventually you have to grow Celebrity Watch up, despite the whole world loving And in New!! and remembering you as a cute magazine child, and the route to adulthood the Love for many former child stars is Island star paved with peril. All too often the Priscilla way that young female stars show Anyabu they are “all grown up” is by Going revealed her Sexy: a couple of fruity pop videos; preferred breakfast, 10 a photoshoot in PVC or lingerie. which possibly 8 “I have lost the power of qualifies as “the most adorableness, but I have gained the unpleasant breakfast yet invented DOWN UP power of hotness!” is the message. by humankind”. Mary Dougie from Unfortunately, the next stage in “Breakfast is usually a bagel with this trajectory is usually “gaining cheese spread, then an egg with grated Wollstonecraft McFly the power of being in your cheese on top served with ketchup,” This week the long- There are those who say that men mid-thirties and putting on 2st”, she said, madly admitting with that awaited statue of can’t be feminists and that they cannot a power that sadly still goes “usually” that this is something that Mary Wollstonecraft help with the Struggle. -

The BBC's Role in the News Media Landscape

The BBC’s Role in the News Media Landscape: The Publishers’ View The BBC Charter Review provides an opportunity for the government to look at the future of the BBC and its evolving role in the wider media landscape. The green paper on Charter Review asks some important questions about the BBC’s scale and scope, funding and governance, and the impact of its ever-growing range of services on commercial media competitors: Does the BBC’s £3.7 billion per year of public funding give it an unfair advantage and distort audience share in a way that undermines commercial business models? Does its huge online presence and extensive free online content damage a wide range of players? Is the BBC able to continue to develop great content to audiences, efficiently and cost effectively while minimising any negative impact on the wider market and maximising any benefits? Is the expansion of the BBC’s services justified in the context of increased choice for audiences? Is the BBC crowding out commercial competition and, if so, is this justified? How should the BBC’s commercial operations, including BBC Worldwide, be reformed? How should the current model of governance and regulation for the BBC be reformed? The News Media Association (NMA), the voice of independent commercial news brands in the UK, believes that the system of BBC governance should place greater obligations on the BBC to work collaboratively – rather than in competition - with the wider news sector. We commissioned Oliver and Ohlbaum Associates (O&O) to examine the changing market for news services and the BBC’s expanding role within that market. -

2015-02-26 Pact Ragdoll.Docx

Robert Kenny & Tim Suter Children’s television – a crisis of choice The case for greater commercial PSB investment in Children’s TV 26 February 2015 About Pact Pact is the UK trade association representing and promoting the commercial interests of independent feature film, television, digital, children’s and animation media companies. About Ragdoll The Ragdoll Foundation is dedicated to developing the power of imaginative responses in children through the arts. The Ragdoll Foundation is governed by a Board of Trustees, chaired by Katherine Wood and its founder is Anne Wood CBE. About the authors Robert Kenny advises companies, regulators and policy makers on issues of TMT strategy and policy. He is the author of numerous papers (academic and professional) and a regular speaker on these topics. Before co-founding Communications Chambers he was MD of Human Capital, a consulting firm. Past roles include heading Strategy and/or M&A for Hongkong Telecom, Reach and Level 3 (all multi- billion dollar telcos). He was also a founder of IncubASIA, a Hong Kong based venture capital firm investing in online businesses. Tim Suter is a founding member of Communications Chambers. He is an advisor on public policy and regulatory issues across the media and communications sectors. He was the founding Ofcom partner with responsibility for content regulation, a member of the statutory Content Board and Deputy Chairman of the Radio Licensing Committee. Before joining Ofcom he was Head of Broadcasting Policy at DCMS, responsible for steering the 2003 Communications Act through to Royal Assent. His broadcasting career at the BBC started in BBC Radio, where he was a drama and documentary producer and editor, before moving to BBC Television as a producer and reporter on Newsnight. -

Shropshire Cover October 2017 .Qxp Shropshire Cover 22/09/2017 14:36 Page 1

Shropshire Cover October 2017 .qxp_Shropshire Cover 22/09/2017 14:36 Page 1 ED GAMBLE AT Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands HENRY TUDOR HOUSE SHROPSHIRE WHAT’S ON OCTOBER 2017 ON OCTOBER WHAT’S SHROPSHIRE Shropshire ISSUE 382 OCTOBER 2017 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On shropshirewhatson.co.uk PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide stepAUSTENTATIOUS back in time at Theatre Severn TWITTER: @WHATSONSHROPS TWITTER: heavenlyMEGSON music and northern humour at The Hive FACEBOOK: @WHATSONSHROPSHIRE GhostlySPOOK-TASTIC! Gaslight returns to Blists Hill Victorian Town SHROPSHIREWHATSON.CO.UK Day of the Friday 10th November The Buttermarket, Shrewsbury tickets available at Dead thebuttermarket.co.uk Niko's F/P October 2017.qxp_Layout 1 25/09/2017 10:44 Page 1 Contents October Shrops.qxp_Layout 1 22/09/2017 12:23 Page 2 October 2017 Contents Disney On Ice - grab your passport for one big adventure at Genting Arena - more on page 45 Carrie Hope Fletcher Matt Lucas Awful Auntie the list talks about being part of talks about life, from Little David Walliams’ much-loved Your 16-page The Addams Family... Britain to Little Me story arrives on stage week-by-week listings guide feature page 8 interview page 19 page 30 page 53 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 15. Music 20. Comedy 24. Theatre 39. Film 42. Visual Arts 44. Events @whatsonwolves @whatsonstaffs @whatsonshrops Wolverhampton What’s On Magazine Staffordshire What’s