Weight Changes Before and After Lurasidone Treatment: a Real‑World Analysis Using Electronic Health Records Jonathan M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Clozapine Is Not Tolerated Mitchell J

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Nursing Capstones Department of Nursing 10-28-2018 When Clozapine is Not Tolerated Mitchell J. Relf Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones Recommended Citation Relf, Mitchell J., "When Clozapine is Not Tolerated" (2018). Nursing Capstones. 268. https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones/268 This Independent Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Nursing at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nursing Capstones by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: WHEN CLOZAPINE IS NOT TOLERATED 1 WHEN CLOZAPINE IS NOT TOLERATED by Mitchell J. Relf Masters of Science in Nursing, University of North Dakota, 2018 An Independent Study Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2018 WHEN CLOZAPINE IS NOT TOLERATED 2 PERMISSION Title When Clozapine is Not Tolerated Department Nursing Degree Master of Science In presenting this independent study in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the College of Nursing and Professional Disciplines of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying or electronic access for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my independent study work or, in her absence, by the chairperson of the department or the dean of the School of Graduate Studies. -

Lurasidone (Latuda) Reference Number: CP.PMN.50 Effective Date: 09.01.15 Last Review Date: 02.21 Line of Business: Commercial, HIM, Medicaid Revision Log

Clinical Policy: Lurasidone (Latuda) Reference Number: CP.PMN.50 Effective Date: 09.01.15 Last Review Date: 02.21 Line of Business: Commercial, HIM, Medicaid Revision Log See Important Reminder at the end of this policy for important regulatory and legal information. Description Lurasidone (Latuda®) is an atypical antipsychotic. FDA Approved Indication(s) Latuda is indicated for the treatment of: • Schizophrenia in adults and adolescents (13 to 17 years) • Depressive episode associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression) in adults and pediatric patients (10 to 17 years) as monotherapy • Depressive episode associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression) in adults as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate Policy/Criteria Provider must submit documentation (such as office chart notes, lab results or other clinical information) supporting that member has met all approval criteria. It is the policy of health plans affiliated with Centene Corporation® that Latuda is medically necessary when the following criteria are met: I. Initial Approval Criteria A. Bipolar Disorder (must meet all): 1. Diagnosis of bipolar disorder; 2. Age ≥ 10 years; 3. Failure of two preferred atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, ziprasidone, quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine) at up to maximally indicated doses, each used for ≥ 4 weeks, unless all are contraindicated or clinically significant adverse effects are experienced; 4. Dose does not exceed 120 mg per day for adults and 80 mg per day for pediatric patients. Approval duration: Medicaid/HIM – 12 months Commercial – Length of Benefit B. Schizophrenia (must meet all): 1. Diagnosis of schizophrenia; 2. Age ≥ 13 years; 3. Failure of two preferred atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, ziprasidone, quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine) at up to maximally indicated doses, each used Page 1 of 6 CLINICAL POLICY Lurasidone for ≥ 4 weeks, unless all are contraindicated or clinically significant adverse effects are experienced; 4. -

Management of Side Effects of Antipsychotics

Management of side effects of antipsychotics Oliver Freudenreich, MD, FACLP Co-Director, MGH Schizophrenia Program www.mghcme.org Disclosures I have the following relevant financial relationship with a commercial interest to disclose (recipient SELF; content SCHIZOPHRENIA): • Alkermes – Consultant honoraria (Advisory Board) • Avanir – Research grant (to institution) • Janssen – Research grant (to institution), consultant honoraria (Advisory Board) • Neurocrine – Consultant honoraria (Advisory Board) • Novartis – Consultant honoraria • Otsuka – Research grant (to institution) • Roche – Consultant honoraria • Saladax – Research grant (to institution) • Elsevier – Honoraria (medical editing) • Global Medical Education – Honoraria (CME speaker and content developer) • Medscape – Honoraria (CME speaker) • Wolters-Kluwer – Royalties (content developer) • UpToDate – Royalties, honoraria (content developer and editor) • American Psychiatric Association – Consultant honoraria (SMI Adviser) www.mghcme.org Outline • Antipsychotic side effect summary • Critical side effect management – NMS – Cardiac side effects – Gastrointestinal side effects – Clozapine black box warnings • Routine side effect management – Metabolic side effects – Motor side effects – Prolactin elevation • The man-in-the-arena algorithm www.mghcme.org Receptor profile and side effects • Alpha-1 – Hypotension: slow titration • Dopamine-2 – Dystonia: prophylactic anticholinergic – Akathisia, parkinsonism, tardive dyskinesia – Hyperprolactinemia • Histamine-1 – Sedation – Weight gain -

Lurasidone for Schizophrenia

Out of the Pipeline Lurasidone for schizophrenia Jana Lincoln, MD, and Aveekshit Tripathi, MD Table 1 n October 2010, the FDA approved lur- A new atypical asidone for the acute treatment of schizo- Lurasidone: Fast facts antipsychotic phrenia at a dose of 40 or 80 mg/d ad- offers once-daily I Brand name: Latuda ministered once daily with food (Table 1). dosing and is well Indication: Schizophrenia in adults tolerated and How it works Approval date: October 28, 2010 Although the drug’s exact mechanism of ac- Availability date: February 2011 considered weight tion is not known, it is thought that lurasi- Manufacturer: Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. neutral done’s antipsychotic properties are related Dosing forms: 40 mg and 80 mg tablets to its antagonism at serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) Recommended dosage: Starting dose: 40 and dopamine D2 receptors.1 mg/d. Maximum dose: 80 mg/d Similar to most other atypical antipsy- chotics, lurasidone has high binding affin- ity for 5-HT2A and D2. Lurasidone has also steady-state concentration is reached within high binding affinity for 5-HT7, 5-HT1A, 7 days.1 Lurasidone is eliminated predomi- and α2C-adrenergic receptors, low affin- nantly through cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 ity for α-1 receptors, and virtually no affin- metabolism in the liver. ity for H1 and M1 receptors (Table 2, page 68). Activity on 5-HT7, 5-HT1A, and α2C- Efficacy adrenergic receptors is believed to enhance Lurasidone’s efficacy for treatment of acute cognition, and 5-HT7 is being studied for a schizophrenia was established in four potential role in mood regulation and sen- 6-week, randomized placebo-controlled clin- sory processing.2,3 Lurasidone’s low activity ical trials.1 The patients were adults (mean on α-1, H1, and M1 receptors suggests a low age: 38.8; range: 18 to 72) who met DSM-IV- risk of orthostatic hypotension, H1-mediat- TR criteria for schizophrenia, didn’t abuse ed sedation and weight gain, and H1- and drugs or alcohol, and had not taken any in- M1-mediated cognitive blunting. -

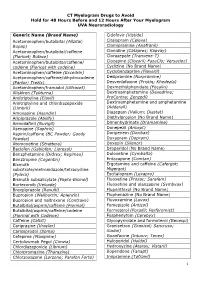

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Clinical Medical & Lurasidone Potentiation of Toxidrome from Drug

Open Journal of Clinical & Medical Volume 4 (2018) Issue 23 Case Reports ISSN 2379-1039 Lurasidone potentiation of toxidrome from drug interaction Mallikarjuna Reddy*; Iouri Banakh; Ashwin Subramaniam *Mallikarjuna Reddy Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Frankston Hospital, 2 Hastings Road, Frankston VIC 3199, Australia Phone: +61 3 9784 7422, Fax: +61 3 9784 8199; Email: [email protected] Abstract Lurasidone, a second generation antipsychotic mediation, is becoming more prevalent in its use due to favourable lower metabolic and cardiac adverse effects. However, long-term eficacy, safety and drug interaction potential of this new drug is not well deined. Here we report a case of 38-year-old woman admitted to intensive care unit with severe refractory hypotension. She was recently initiated on lurasidone therapy as a hypnotic for insomnia management in addition to several regular treatments for her comorbidities including: Quetiapine, paroxetine, lamotrigine, atorvastatin and diazepam. There is limited data on use of intralipid emulsion in severe cardiotoxicity from newer antipsychotics, but when it was used in this case of suspected lurasidone overdose, her profound shock state responded rapidly, with fast weaning off extremely high doses ofepinephrine, norepinephrine and vasopressin. Keywords lurasidone; hypotension; polypharmacy overdose; drug interactions; intralipid; intensive Introduction Patients with psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, suffer from multiple medical comorbidities and substance abuse conditions [1]. Polypharmacy that these patients are exposed to places them at an increased risk of drug interactions and adverse events [2]. The use of new antipsychotic agents with lower metabolic disturbance and cardiac adverse effect proile such as lurasidone is preferable; however long-term eficacy, safety and drug interaction potential is not well deined. -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

Effects of Subchronic Administrations of Vortioxetine, Lurasidone, And

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Effects of Subchronic Administrations of Vortioxetine, Lurasidone, and Escitalopram on Thalamocortical Glutamatergic Transmission Associated with Serotonin 5-HT7 Receptor Motohiro Okada * , Ryusuke Matsumoto, Yoshimasa Yamamoto and Kouji Fukuyama Department of Neuropsychiatry, Division of Neuroscience, Graduate School of Medicine, Mie University, Tsu 514-8507, Japan; [email protected] (R.M.); [email protected] (Y.Y.); [email protected] (K.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-59-231-5018 Abstract: The functional suppression of serotonin (5-HT) type 7 receptor (5-HT7R) is forming a basis for scientific discussion in psychopharmacology due to its rapid-acting antidepressant-like action. A novel mood-stabilizing atypical antipsychotic agent, lurasidone, exhibits a unique receptor-binding profile, including a high affinity for 5-HT7R antagonism. A member of a novel class of antidepres- sants, vortioxetine, which is a serotonin partial agonist reuptake inhibitor (SPARI), also exhibits a higher affinity for serotonin transporter, serotonin receptors type 1A (5-HT1AR) and type 3 (5-HT3R), and 5-HT7R. However, the effects of chronic administration of lurasidone, vortioxetine, and the selec- Citation: Okada, M.; Matsumoto, R.; tive serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), escitalopram, on 5-HT7R function remained to be clarified. Yamamoto, Y.; Fukuyama, K. Effects Thus, to explore the mechanisms underlying the clinical effects of vortioxetine, escitalopram, and of Subchronic Administrations of lurasidone, the present study determined the effects of these agents on thalamocortical glutamatergic Vortioxetine, Lurasidone, and transmission, which contributes to emotional/mood perception, using multiprobe microdialysis Escitalopram on Thalamocortical and 5-HT7R expression using capillary immunoblotting. -

Pharmacology Review(S)

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 200603 PHARMACOLOGY REVIEW(S) Tertiary Pharmacology/Toxicology Review From: Paul C. Brown, Ph.D., ODE Associate Director for Pharmacology and Toxicology, OND IO NDA: 200603 Agency receipt date: 12/30/2009 Drug: Lurasidone hydrochloride Applicant: Sunovion Pharmaceuticals (Originally submitted by Dainippon Sumimoto Pharma America, Inc.) Indication: schizophrenia Reviewing Division: Division of Psychiatry Products Background: The pharm/tox reviewer and team leader concluded that the nonclinical data support approval of lurasidone for the indication listed above. Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity: Reproductive and developmental toxicity studies in rats and rabbits revealed no evidence of teratogenicity or embryofetal toxicity. The high doses in the rat and rabbit embryofetal toxicity studies were 3 and 12 times, respectively, the maximum recommended human dose (80 mg) based on a body surface area comparison. Carcinogenicity: Lurasidone was tested in 2 year rat and mouse carcinogenicity studies. These studies were reviewed by the division and the executive carcinogenicity assessment committee. The committee concluded that the studies were adequate and that there was a drug-related increase in mammary carcinomas in female rats at doses of 12 mg/kg and higher and a drug-related increase in mammary carcinomas and adenoacanthomas and pituitary pars distalis adenomas in female mice. The applicant also provided data from various studies showing that lurasidone significantly increases prolactin in several different species including rats and mice. Conclusions: I agree with the division pharm/tox conclusion that this application can be approved from a pharm/tox perspective. The division recommends that lurasidone be labeled with pregnancy category B. -

Psychotropic Drug Indications

PSYCHOTROPIC DRUG INDICATIONS (Part 1 of 2) Bipolar Disorder Mixed Generic Brand Form Mania Depression Episodes Maintenance MDD TRD PMDD Schizophrenia Others4 ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS aripiprazole — tabs, ODT, oral √ √ √ √1 √ √ soln Abilify tabs √ √ √ √1 √ √ Abilify ext-rel IM inj √ √ Maintena Abilify tabs with √ √ √ √1 √ Mycite sensor aripiprazole Aristada ext-rel IM inj √ lauroxil Aristada ext-rel IM inj √ Initio asenapine Saphris sublingual tabs √ √ √ √ brexpiprazole Rexulti tabs √1 √ cariprazine Vraylar caps √ √ √ √ lurasidone Latuda tabs √ √ olanzapine Zyprexa tabs √ √2 √ √ √2 √ IM inj √ Zyprexa ext-rel IM inj √ Relprevv Zyprexa ODT √ √2 √ √ √2 √ Zydis quetiapine Seroquel tabs √ √ √ √ Seroquel XR ext-rel tabs √ √ √ √ √1 √ risperidone Perseris ext-rel SC inj √ Risperdal tabs, oral soln √ √ √ √ Risperdal ext-rel IM inj √ √ Consta Risperdal ODT √ √ √ √ M-tabs ziprasidone Geodon caps √ √ √1 √ IM inj √ COMBINATION ATYPICAL & SELECTIVE SEROTONIN REUPTAKE INHIBITOR olanzapine + Symbyax caps √ √ fluoxetine MONOAMINE OXIDASE INHIBITORS (MAOIs) phenelzine Nardil tabs √ selegiline EMSAM transdermal √ system tranylcypromine Parnate tabs √ SEROTONIN AND NOREPINEPHRINE REUPTAKE INHIBITORS (SNRIs) desvenlafaxine Khedezla ext-rel tabs √ Pristiq ext-rel tabs √ duloxetine Cymbalta caps √ √ levomilnacipran Fetzima ext-rel caps √ venlafaxine — scored tabs √ Effexor XR ext-rel caps √ √ SELECTIVE SEROTONIN REUPTAKE INHIBITORS (SSRIs) citalopram Celexa scored tabs √ escitalopram Lexapro scored tabs, √ √ oral soln fluoxetine — tabs, oral soln √3 √ √3 √ Prozac -

Currently Prescribed Psychotropic Medications

CURRENTLY PRESCRIBED PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATIONS Schizophrenia Depression Anxiety Disorders 1st generation antipsychotics: Tricyclics: Atarax (hydroxyzine) Haldol (haloperidol), *Anafranil (clomipramine) Ativan (lorazepam) Haldol Decanoate Asendin (amoxapine) BuSpar (buspirone) Loxitane (loxapine) Elavil (amitriptyline) *Inderal (propranolol) Mellaril (thioridazine) Norpramin (desipramine) Keppra (levetiracetam) Navane (thiothixene) Pamelor (nortriptyline) *Klonopin (clonazepam) Prolixin (fluphenazine), Prolixin Sinequan (doxepin) Librium (chlordiazepoxide) Decanoate Spravato (esketamine) Serax (oxazepam) Stelazine (trifluoperazine) Surmontil (trimipramine) Thorazine (chlorpromazine) *Tenormin (atenolol) Tofranil (imipramine) MEDICATIONS PSYCHOTROPIC PRESCRIBED CURRENTLY Trilafon (perphenazine) Tranxene (clorazepate) Vivactil (protriptyline) Valium (diazepam) 2nd generation antipsychotics: Zulresso (brexanolone) Vistaril (hydroxyzine) Abilify (aripiprazole) Aristada (aripiprazole) SSRIs: Xanax (alprazolam) Caplyta (lumateperone) Celexa (citalopram) *Antidepressants, especially SSRIs, are also used in the treatment of anxiety. Clozaril (clozapine) Lexapro (escitalopram) Fanapt (iloperidone) *Luvox (fluvoxamine) Geodon (ziprasidone) Paxil (paroxetine) Stimulants (used in the treatment of ADD/ADHD) Invega (paliperidone) Prozac (fluoxetine) Invega Sustenna Zoloft (sertraline) Adderall (amphetamine and Perseris (Risperidone injectable) dextroamphetamine) Latuda (lurasidone) MAOIs: Azstarys(dexmethylphenidate Rexulti (brexpiprazole) Emsam (selegiline) -

The Effectiveness of Lurasidone Add-On for Residual Aggressive

children Communication The Effectiveness of Lurasidone Add-On for Residual Aggressive Behavior and Obsessive Symptoms in Antipsychotic-Treated Children and Adolescents with Tourette Syndrome: Preliminary Evidence from a Case Series Marco Colizzi 1,2,3,* , Riccardo Bortoletto 3 and Leonardo Zoccante 3 1 Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neurosciences, Biomedicine and Movement Sciences, University of Verona, 37134 Verona, Italy 2 Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London SE5 8AF, UK 3 Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatry Unit, Maternal-Child Integrated Care Department, Integrated University Hospital of Verona, 37126 Verona, Italy; [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (L.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-045-812-6832 Abstract: Children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome may suffer from comorbid psychological and behavioral difficulties, primarily Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder-related manifestations including impulsive, aggressive, and disruptive behavior, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder- related disturbances. Often, such additional problems represent the major cause of disability, re- quiring their prioritization above the tic symptomatology. Here, we present six cases of children Citation: Colizzi, M.; Bortoletto, R.; and adolescents with treatment-resistant Tourette syndrome aged 11–17 years, whose symptoms, Zoccante, L. The Effectiveness of especially the non-tic symptoms such as aggressive behavior and obsessive symptoms, failed to Lurasidone Add-On for Residual respond adequately to at least two different antipsychotics and, where deemed appropriate, to a Aggressive Behavior and Obsessive combination with a medication with a different therapeutic indication or chemical class (e.g., antide- Symptoms in Antipsychotic-Treated pressant or anticonvulsant).