The Effectiveness of Lurasidone Add-On for Residual Aggressive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Clozapine Is Not Tolerated Mitchell J

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Nursing Capstones Department of Nursing 10-28-2018 When Clozapine is Not Tolerated Mitchell J. Relf Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones Recommended Citation Relf, Mitchell J., "When Clozapine is Not Tolerated" (2018). Nursing Capstones. 268. https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones/268 This Independent Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Nursing at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nursing Capstones by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: WHEN CLOZAPINE IS NOT TOLERATED 1 WHEN CLOZAPINE IS NOT TOLERATED by Mitchell J. Relf Masters of Science in Nursing, University of North Dakota, 2018 An Independent Study Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2018 WHEN CLOZAPINE IS NOT TOLERATED 2 PERMISSION Title When Clozapine is Not Tolerated Department Nursing Degree Master of Science In presenting this independent study in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the College of Nursing and Professional Disciplines of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying or electronic access for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my independent study work or, in her absence, by the chairperson of the department or the dean of the School of Graduate Studies. -

Lumateperone Monograph

Lumateperone (Caplyta®) Classification Atypical antipsychotic Pharmacology The mechanism of action of lumateperone tosylate (Caplyta, ITI-007) in the treatment of schizophrenia is unknown but it’s thought to simultaneously modulate serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate neurotransmission. Specifically, lumateperone acts as a potent 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, a D2 receptor presynaptic partial agonist and postsynaptic antagonist, a D1 receptor-dependent modulator of glutamate, and a serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Indication Treatment of schizophrenia in adults Boxed Warning Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Caplyta is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis. Pharmacokinetics Pharmacokinetic Parameter Details Absorption Rapidly absorbed. Absolute bioavailability is about 4.4%. Cmax reached approximately 1 (fasting) to 2 h (food) post dosing. Ingestion of high fat meal lowers mean Cmax by 33% and increases mean AUC by 9% Distribution Protein binding = 97.4%. Volume of distribution (IV) = 4.1 L/kg Metabolism Extensively metabolized. T1/2 = 13-21 hours for lumateperone and metabolites Excretion Less than 1% excreted unchanged in urine 1 Texas Health and Human Services ● hhs.texas.gov Dosage/Administration 42 mg by mouth once daily with food. Dose titration is not required. Use in Special Population Pregnancy Neonates exposed to antipsychotic drugs during the third trimester are at risk for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms following delivery. Available data from Caplyta use in pregnant women are insufficient to establish any drug associated risks for birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes. There are risks to the mother associated with untreated schizophrenia and with exposure to antipsychotics, including Caplyta, during pregnancy. -

Lurasidone (Latuda) Reference Number: CP.PMN.50 Effective Date: 09.01.15 Last Review Date: 02.21 Line of Business: Commercial, HIM, Medicaid Revision Log

Clinical Policy: Lurasidone (Latuda) Reference Number: CP.PMN.50 Effective Date: 09.01.15 Last Review Date: 02.21 Line of Business: Commercial, HIM, Medicaid Revision Log See Important Reminder at the end of this policy for important regulatory and legal information. Description Lurasidone (Latuda®) is an atypical antipsychotic. FDA Approved Indication(s) Latuda is indicated for the treatment of: • Schizophrenia in adults and adolescents (13 to 17 years) • Depressive episode associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression) in adults and pediatric patients (10 to 17 years) as monotherapy • Depressive episode associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression) in adults as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate Policy/Criteria Provider must submit documentation (such as office chart notes, lab results or other clinical information) supporting that member has met all approval criteria. It is the policy of health plans affiliated with Centene Corporation® that Latuda is medically necessary when the following criteria are met: I. Initial Approval Criteria A. Bipolar Disorder (must meet all): 1. Diagnosis of bipolar disorder; 2. Age ≥ 10 years; 3. Failure of two preferred atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, ziprasidone, quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine) at up to maximally indicated doses, each used for ≥ 4 weeks, unless all are contraindicated or clinically significant adverse effects are experienced; 4. Dose does not exceed 120 mg per day for adults and 80 mg per day for pediatric patients. Approval duration: Medicaid/HIM – 12 months Commercial – Length of Benefit B. Schizophrenia (must meet all): 1. Diagnosis of schizophrenia; 2. Age ≥ 13 years; 3. Failure of two preferred atypical antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, ziprasidone, quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine) at up to maximally indicated doses, each used Page 1 of 6 CLINICAL POLICY Lurasidone for ≥ 4 weeks, unless all are contraindicated or clinically significant adverse effects are experienced; 4. -

Atypical Antipsychotics TCO 02.2018

Therapeutic Class Overview Atypical Antipsychotics INTRODUCTION • Antipsychotic medications have been used for over 50 years to treat schizophrenia and a variety of other psychiatric disorders (Miyamato et al 2005). • Antipsychotic medications generally exert their effect in part by blocking dopamine (D)-2 receptors (Jibson et al 2017). • Antipsychotics are divided into 2 distinct classes based on their affinity for D2 and other neuroreceptors: typical antipsychotics, also called first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs), and atypical antipsychotics, also called second- generation antipsychotics (SGAs) (Miyamato et al 2005). • Atypical antipsychotics do not have a uniform pharmacology or mechanism of action; these differences likely account for the different safety and tolerability profiles of these agents (Clinical Pharmacology 2020, Jibson et al 2017). The atypical antipsychotics differ from the early antipsychotics in that they have affinity for the serotonin 5-HT2 receptor in addition to D2. Clozapine is an antagonist at all dopamine receptors (D1-5), with lower affinity for D1 and D2 receptors and high affinity for D4 receptors. Aripiprazole and brexpiprazole act as partial agonists at the D2 receptor, functioning as an ○ agonist when synaptic dopamine levels are low and as an antagonist when they are high. Cariprazine is a partial agonist at D2 and D3. Pimavanserin does not have dopamine blocking activity and is primarily an inverse agonist at 5-HT2A receptors. The remaining atypical antipsychotics share the similarity of D2 and 5-HT2A -

Management of Side Effects of Antipsychotics

Management of side effects of antipsychotics Oliver Freudenreich, MD, FACLP Co-Director, MGH Schizophrenia Program www.mghcme.org Disclosures I have the following relevant financial relationship with a commercial interest to disclose (recipient SELF; content SCHIZOPHRENIA): • Alkermes – Consultant honoraria (Advisory Board) • Avanir – Research grant (to institution) • Janssen – Research grant (to institution), consultant honoraria (Advisory Board) • Neurocrine – Consultant honoraria (Advisory Board) • Novartis – Consultant honoraria • Otsuka – Research grant (to institution) • Roche – Consultant honoraria • Saladax – Research grant (to institution) • Elsevier – Honoraria (medical editing) • Global Medical Education – Honoraria (CME speaker and content developer) • Medscape – Honoraria (CME speaker) • Wolters-Kluwer – Royalties (content developer) • UpToDate – Royalties, honoraria (content developer and editor) • American Psychiatric Association – Consultant honoraria (SMI Adviser) www.mghcme.org Outline • Antipsychotic side effect summary • Critical side effect management – NMS – Cardiac side effects – Gastrointestinal side effects – Clozapine black box warnings • Routine side effect management – Metabolic side effects – Motor side effects – Prolactin elevation • The man-in-the-arena algorithm www.mghcme.org Receptor profile and side effects • Alpha-1 – Hypotension: slow titration • Dopamine-2 – Dystonia: prophylactic anticholinergic – Akathisia, parkinsonism, tardive dyskinesia – Hyperprolactinemia • Histamine-1 – Sedation – Weight gain -

Lurasidone for Schizophrenia

Out of the Pipeline Lurasidone for schizophrenia Jana Lincoln, MD, and Aveekshit Tripathi, MD Table 1 n October 2010, the FDA approved lur- A new atypical asidone for the acute treatment of schizo- Lurasidone: Fast facts antipsychotic phrenia at a dose of 40 or 80 mg/d ad- offers once-daily I Brand name: Latuda ministered once daily with food (Table 1). dosing and is well Indication: Schizophrenia in adults tolerated and How it works Approval date: October 28, 2010 Although the drug’s exact mechanism of ac- Availability date: February 2011 considered weight tion is not known, it is thought that lurasi- Manufacturer: Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. neutral done’s antipsychotic properties are related Dosing forms: 40 mg and 80 mg tablets to its antagonism at serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) Recommended dosage: Starting dose: 40 and dopamine D2 receptors.1 mg/d. Maximum dose: 80 mg/d Similar to most other atypical antipsy- chotics, lurasidone has high binding affin- ity for 5-HT2A and D2. Lurasidone has also steady-state concentration is reached within high binding affinity for 5-HT7, 5-HT1A, 7 days.1 Lurasidone is eliminated predomi- and α2C-adrenergic receptors, low affin- nantly through cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 ity for α-1 receptors, and virtually no affin- metabolism in the liver. ity for H1 and M1 receptors (Table 2, page 68). Activity on 5-HT7, 5-HT1A, and α2C- Efficacy adrenergic receptors is believed to enhance Lurasidone’s efficacy for treatment of acute cognition, and 5-HT7 is being studied for a schizophrenia was established in four potential role in mood regulation and sen- 6-week, randomized placebo-controlled clin- sory processing.2,3 Lurasidone’s low activity ical trials.1 The patients were adults (mean on α-1, H1, and M1 receptors suggests a low age: 38.8; range: 18 to 72) who met DSM-IV- risk of orthostatic hypotension, H1-mediat- TR criteria for schizophrenia, didn’t abuse ed sedation and weight gain, and H1- and drugs or alcohol, and had not taken any in- M1-mediated cognitive blunting. -

Lumateperone for Acute Exacerbations of Psychosis in Schizophrenia NIHRIO (HSRIC) ID: 10603 NICE ID: 9131

NIHR Innovation Observatory Evidence Briefing: May 2017 Lumateperone for acute exacerbations of psychosis in schizophrenia NIHRIO (HSRIC) ID: 10603 NICE ID: 9131 LAY SUMMARY Schizophrenia is a chronic mental health disorder causing changes in people’s thoughts and behaviour. Common symptoms include hallucinations (experiencing things that aren’t there), delusions (strong and unusual beliefs), confusion and disorganised thoughts. Schizophrenic symptoms usually come and go in ‘episodes’, where for a period of time symptoms may become more severe. Schizophrenia is usually treated with different types of psychological therapies and antipsychotic drugs which alter the levels of chemicals such as dopamine and serotonin in the brain. However, antipsychotic drugs can cause side effects including drowsiness, weight gain, blurred vision, constipation, lack of libido and dry mouth. Lumateperone is a new, orally administered antipsychotic drug which alters levels of several chemicals in the brain including dopamine, serotonin and glutamate. Studies on lumateperone in people with schizophrenia experiencing an episode of severe symptoms suggest it may reduce symptoms with less side effects than current antipsychotic medication. If licensed lumateperone may provide an alternative treatment option for people with schizophrenia which may cause fewer side effects. This briefing is based on information available at the time of research and a limited literature search. It is not intended to be a definitive statement on the safety, efficacy or effectiveness of the health technology covered and should not be used for commercial purposes or commissioning without additional information. This briefing presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed1 are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. -

Weight Changes Before and After Lurasidone Treatment: a Real‑World Analysis Using Electronic Health Records Jonathan M

Meyer et al. Ann Gen Psychiatry (2017) 16:36 DOI 10.1186/s12991-017-0159-x Annals of General Psychiatry PRIMARY RESEARCH Open Access Weight changes before and after lurasidone treatment: a real‑world analysis using electronic health records Jonathan M. Meyer1, Daisy S. Ng‑Mak2* , Chien‑Chia Chuang3, Krithika Rajagopalan2 and Antony Loebel4 Abstract Background: Severe and persistent mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, are associated with increased risk of obesity compared to the general population. While the association of lurasidone and lower risk of weight gain has been established in short and longer-term clinical trial settings, information about lurasidone’s asso‑ ciation with weight gain in usual clinical care is limited. This analysis of usual clinical care evaluated weight changes associated with lurasidone treatment in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Methods: A retrospective, longitudinal analysis was conducted using de-identifed electronic health records from the Humedica database for patients who initiated lurasidone monotherapy between February 2011 and Novem‑ ber 2013. Weight data were analyzed using longitudinal mixed-efects models to estimate the impact of lurasidone on patient weight trajectories over time. Patients’ weight data (kg) were tracked for 12-months prior to and up to 12-months following lurasidone initiation. Stratifed analyses were conducted based on prior use of second-genera‑ tion antipsychotics with medium/high risk (clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone) versus low risk (aripipra‑ zole, ziprasidone, frst-generation antipsychotics, or no prior antipsychotics) for weight gain. Results: Among the 439 included patients, the mean age was 42.2 years, and 69.7% were female. -

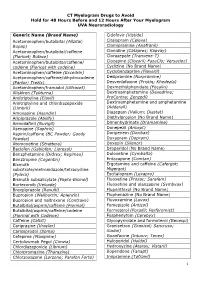

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Clinical Medical & Lurasidone Potentiation of Toxidrome from Drug

Open Journal of Clinical & Medical Volume 4 (2018) Issue 23 Case Reports ISSN 2379-1039 Lurasidone potentiation of toxidrome from drug interaction Mallikarjuna Reddy*; Iouri Banakh; Ashwin Subramaniam *Mallikarjuna Reddy Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Frankston Hospital, 2 Hastings Road, Frankston VIC 3199, Australia Phone: +61 3 9784 7422, Fax: +61 3 9784 8199; Email: [email protected] Abstract Lurasidone, a second generation antipsychotic mediation, is becoming more prevalent in its use due to favourable lower metabolic and cardiac adverse effects. However, long-term eficacy, safety and drug interaction potential of this new drug is not well deined. Here we report a case of 38-year-old woman admitted to intensive care unit with severe refractory hypotension. She was recently initiated on lurasidone therapy as a hypnotic for insomnia management in addition to several regular treatments for her comorbidities including: Quetiapine, paroxetine, lamotrigine, atorvastatin and diazepam. There is limited data on use of intralipid emulsion in severe cardiotoxicity from newer antipsychotics, but when it was used in this case of suspected lurasidone overdose, her profound shock state responded rapidly, with fast weaning off extremely high doses ofepinephrine, norepinephrine and vasopressin. Keywords lurasidone; hypotension; polypharmacy overdose; drug interactions; intralipid; intensive Introduction Patients with psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, suffer from multiple medical comorbidities and substance abuse conditions [1]. Polypharmacy that these patients are exposed to places them at an increased risk of drug interactions and adverse events [2]. The use of new antipsychotic agents with lower metabolic disturbance and cardiac adverse effect proile such as lurasidone is preferable; however long-term eficacy, safety and drug interaction potential is not well deined. -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

Lumateperone (Caplyta®) New Drug Update

Lumateperone (Caplyta®) New Drug Update January 2020 Nonproprietary Name lumateperone Brand Name Caplyta Manufacturer Intra-Cellular Therapies Form Capsule Strength 42 mg FDA Approval December 20, 2019 Market Availability Available FDA Approval Classification Standard Review FDB Classification- Specific Antipsychotic, Atypical, Dopamine, Serotonin Antagonist (H7T) Therapeutic Class (HIC3) INDICATION1 Lumateperone (Caplyta) is an atypical antipsychotic indicated for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults. The exact mechanism of action of lumateperone in schizophrenia is unknown but it is thought to provide selective and simultaneous modulation of serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate. PHARMACOKINETICS Once daily administration of lumateperone will lead to steady state in approximately 5 days, with increases in exposure proportional to the dose. The maximum concentration (Cmax) of lumateperone is reached approximately 1 to 2 hours after the dose. Administration with food will delay the time to maximum concentration (Tmax) by approximately 1 hour, and a high fat meal would result in a decrease in Cmax of approximately 33%. Lumateperone is 97.4% protein bound. Lumateperone is extensively metabolized to over 20 metabolites with various enzymes involved, including uridine 5'-diphospho- glucuronosyltransferases (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, UGT) 1A1, 1A4, and 2B15, aldoketoreductase (AKR) 1C1, 1B10, and 1C4, and cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4, 2C8, and 1A2. The terminal half-life is approximately 18 hours after intravenous administration. A human mass-balance study demonstrated <1% of the radioactive dose was excreted as unchanged in the urine, with 58% and 29% recovered in the urine and feces, respectively. CONTRAINDICATIONS/WARNINGS Contraindications for lumateperone include known hypersensitivity to the active ingredient or any of the components. Proprietary Information.