Biblical Annotations and Theological Interpretation in Modern Catholic and Protestant English-Language Bibles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About the New Scofield Reference Bible

About the New Scofield Reference Bible Dr. Peter S. Ruckman B.A., B.D., M.A., Th.M., Ph.D. President and Founder of Pensacola Bible Institute Copyright © 1979 by Peter S. Ruckman All rights reserved (PRINT) ISBN 1-58026-200-7 BB BOOKSTORE P.O. Box 7135 Pensacola, FL 32534 PUBLISHER’S NOTE The Scripture quotations found herein are from the text of the Authorized King James Version of the Bible. Any deviations therefrom are not intentional. Table of Contents About The New Scofield Reference Bible About The New Scofield Reference Bible Now we are going to get highly technical tonight, but we aren’t going to be any more critical of the New Scofield Reference Bible than the New Scofield board of editors were of the King James Bible. Those of us who believe the King James Bible have a great advantage over those who don’t. That is, we can be just as critical as we want toward any of its revisors or correctors because their attitude towards it is appalling, if not downright atrocious; and that is not an overstatement. (I have often been accused of overstatement by ignorant people who don’t check facts.) The attacks made upon the Authorized Bible by conservatives are such that the worst thing one could say about the attackers wouldn’t be enough. In this message we want to show the Christian, the born-again child of God (the true Bible-believer), why he should never be deceived for a minute by such non-Christian publications as the New American Standard Version or its sister, the American Standard Version, 1901, or this watered-down, anemic edition I have in my lap called the New Scofield Reference Bible. -

Various Translations of Psalm 23A

Various Translations of Psalm 23a Jeffrey D. Oldham 2006 Feb 17 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 List of Abbreviations . 4 I Translations in the Tyndale-King James Tradition 5 2 The King James Version (1611) 5 3 The Revised Version (1885) 6 4 American Standard Version (1901) 7 5 Revised Standard Version (1952) 8 6 New Revised Standard Version (1989) 9 7 New American Standard (1971) 10 8 New King James Version (1982) 11 II Catholic Translations 12 9 Rheims-Douay (1610) 12 10 Knox (1950) 13 11 The Jerusalem Bible (1966) 14 12 The New Jerusalem Bible (1985) 15 13 The New American Bible (1970) 16 III Jewish Translations 17 a c 2005 Jeffrey D. Oldham ([email protected]). All rights reserved. This document may not be distributed in any form without the express permission of the author. 14 The JPS’s Masoretic Translation (1917) 17 15 The Tanakh (1985) 18 IV British Translations 19 16 The New English Bible (1970) 19 17 Revised English Bible (1989) 20 V Conservative Protestant Translations 21 18 Amplified Bible (1965) 21 19 New International Version (1978) 22 20 English Standard Version (2001) 23 21 The New Living Translation (1996) 24 VI Modern Language and Easy-to-Read Translations 25 22 Moffatt (1926) 25 23 Smith-Goodspeed (1927) 26 24 Basic English Bible (1949) 27 25 New Berkeley Version (1969) 28 26 Today’s English Version (1976) 29 27 Contemporary English Version (1995) 30 28 New Century Version (1991) 31 VII Paraphrases 32 29 The Living Bible (1971) 32 30 The Message (2002) 33 VIII Other 34 31 Septuagint Bible by Charles Thomson (1808) 34 2 1 Introduction There are about two dozen English-language Bibles currently in circulation in the States and about as many have previously been in circulation, but few of us ever examine more the our favorite translation. -

January 3, 2007

HOW TO CITE THE BIBLE Guide for Four Citation Styles: MLA, APA, SBL, CHICAGO MLA [Refer to MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, 7th ed. (2009), sections 6.4.8, 7.7.1]. Copy at Reference Desk. General Do not italicize, underline, or use quotation marks for books and versions of the Bible. Do italicize the titles of individual published editions of the Bible. Example: The King James Version of the Bible was originally published in 1611. Example: The New Oxford Annotated Bible includes maps of the Holy Land. In-Text Citations Abbreviate titles of books. [See section 7.7.1 for lists of abbreviations of Old and New Testament books]. Examples: Gen. 1.1-2 (Phil. 3.8) [parenthetical citation] Note: Use a period to separate chapter and verse. For a first parenthetical citation to a particular version, cite the name, followed by a comma, and then the passage. Examples: (New International Version, Gen. 3.15) (New Jerusalem Bible, Ezek. 2.6-8) For subsequent references, do not identify the version, unless you use a different version. Works Cited (i.e. Bibliography) Include the title of the Bible, the version, and publication information (city, publisher, year), followed by Print or Web designation. Example: Zondervan NIV Study Bible. Fully rev. ed. Kenneth L. Barker, gen. ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002. Print. Example: The English Standard Version Bible: Containing the Old and New Testaments with Apocrypha. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. Print. Example: New International Version. [Colorado Springs]: Biblica, 2011. BibleGateway.com. Web. 3 Mar. 2011. 2 APA [Refer to Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th ed. -

Richard Challoner School Manor Drive North, New Malden, Surrey KT3 5PE Tel: 020 8330 5947

Richard Challoner School Manor Drive North, New Malden, Surrey KT3 5PE Tel: 020 8330 5947 TEACHER OF ART, maternity cover, 0.6 FTE Start date: 1st September 2021 Salary dependent upon experience, Outer London payscale, NQT’s welcome to apply. Teachers’ Pension Scheme onsite gym facilities; onsite parking; preschool nursery within the grounds A fantastic opportunity has arisen for you to join a school where you will be valued and appreciated by pupils, colleagues and parents alike; where our CPD programme has been recognised as exceptional and the caring and supportive environment means that staff turnover is incredibly low. Students’ behaviour is impeccable, they treat each other and staff with real respect, have a genuine enjoyment of school and enjoy their learning. Our students and staff are proud of their school and work hard to be the best that they can be. Richard Challoner is a very successful school with an excellent reputation, is consistently oversubscribed, and has a genuinely comprehensive intake. There are many opportunities for staff and pupil involvement in whole school fun, through many house activities, in sports, art, drama and music in particular. We passionately believe that Art enriches and enhances the lives of young people. The successful candidate should have skill, confidence and proficiency in a number of mediums and knowledge of a range of different Artists, designers and craftspeople. They should also be able to bring new ideas to the department and help develop schemes of work and different ways of working. The department offers a wide range of extra-curricular opportunities and a desire to be involved with this is extremely important. -

From Confederate Deserter to Decorated Veteran Bible Scholar: Exploring the Enigmatic Life of C.I

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2011 From Confederate Deserter to Decorated Veteran Bible Scholar: Exploring the Enigmatic Life of C.I. Scofield 1861-1921. D. Jean Rushing East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Rushing, D. Jean, "From Confederate Deserter to Decorated Veteran Bible Scholar: Exploring the Enigmatic Life of C.I. Scofield 1861-1921." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1380. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1380 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Confederate Deserter to Decorated Veteran Bible Scholar: Exploring the Enigmatic Life of C.I. Scofield, 1861-1921 _____________________ A Thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _____________________ by D. Jean Rushing December 2011 _____________________ Dr. William Burgess, Chair Dr. Leila al-Imad Dr. Tom Lee Keywords: C. I. Scofield, Dispensationalism, Fundamentalism, The Scofield Reference Bible, Confederate Soldier, Manhood ABSTRACT From Confederate Deserter to Decorated Veteran Bible Scholar: Exploring the Enigmatic Life of C.I. Scofield, 1861-1921 by D. Jean Rushing Cyrus Ingerson Scofield portrayed himself as a decorated Confederate veteran, a successful lawyer, and a Bible scholar who was providentially destined to edit his 1909 dispensational opus, The Scofield Reference Bible. -

Orthodox Study Bible Yearly Reading Plan - 1

Orthodox Study Bible Yearly Reading Plan - 1 - Date Day Old Testament Psalms Proverbs New Testament Jan 1 1. Gn 1–3 1; 2 1:1–5 Mt 1 2. 2. Gn 4–7 3; 4 1:6–10 Mt 2 3. 3. Gn 8:1—11:9 5 1:11–15 Mt 3 4. 4. Gn 11:10—15:21 6 1:16–19 Mt 4 5. 5. Gn 16—18 7 1:20–24 Mt 5:1–20 6. 6. Gn 19—21 8 1:25–29 Mt 5:21–48 7. 7. Gn 22—24:49 9:1–17 1:30–35 Mt 6:1–18 8. 8. Gn 24:50—26:35 9:18–39 2:1–5 Mt 6:19–34 9. 9. Gn 27; 28 10; 11 2:6–9 Mt 7 10. 10. Gn 29; 30 12; 13 2:10–16 Mt 8:1–17 11. 11. Gn 31; 32 14; 15 2:17–23 Mt 8:18–34 12. 12. Gn33—35 16 3:1–5 Mt 9:1–17 13. 13. Gn36; 37 17:1–17 3:6–10 Mt 9:18–38 14. 14. Gn 38—40 17:18–32 3:11–16 Mt 10:1–23 15. 15. Gn 41; 42 17:33–51 3:17–22 Mt 10:24–42 16. 16. Gn 43—45 18 3:23–27 Mt 11 17. 17. Gn 46—48 19 3:28–32 Mt 12:1–21 18. 18. Gn 49; 50 20 3:33–38 Mt 12:22–50 19. 19. -

Opening God's Word to the World

AMERICAN BIBLE SOCIETY | 2013 ANNUAL REPORT STEWARDSHIP God’S WORD GOES FORTH p.11 HEALING TRAUMA’S WOUNDS p.16 THE CHURCh’S ONE FOUNDATION p.22 OPENING GOd’s WORD TO THE WORLD A New Chapter in God’s Story CONTENTS Dear Friends, Now it is our turn. As I reflect on the past year at American Bible Society, I am Nearly, 2,000 years later, we are charged with continuing this 4 PROVIDE consistently reminded of one thing: the urgency of the task before important work of opening hands, hearts and minds to God’s God’s Word for Millions Still Waiting us. Millions of people are waiting to hear God speak to them Word. I couldn’t be more excited to undertake this endeavor with through his Word. It is our responsibility—together with you, our our new president, Roy Peterson, and his wife, Rita. 6 Extending Worldwide Reach partners—to be faithful to this call to open hands, hearts and Roy brings a wealth of experience and a passionate heart for 11 God’s Word Goes Forth minds to the Bible’s message of salvation. Bible ministry from his years as president and CEO of The Seed This task reminds me of a story near the end of the Gospel Company since 2003 and Wycliffe USA from 1997-2003. He of Luke. Jesus has returned to be with his disciples after the has served on the front lines of Bible translation in Ecuador and resurrection. While he is eating fish and talking with his disciples, Guatemala with Wycliffe’s partner he “opened their minds to understand the Scriptures.” Luke 24.45 organization SIL. -

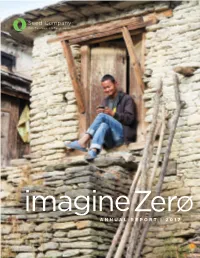

ANNUAL REPORT | 2017 | ANNUAL REPORT Imagine Imagine

Ø Zer ANNUAL REPORT | 2017 | ANNUAL REPORT imagine SEED COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT | 2017 GREETINGS IN JESUS’ NAME SAMUEL E. CHIANG | President and CEO 2 3 _ _ We praise God for Fiscal Year 2017. With the unaudited numbers in, I’m humbled and happy to report that FY17 contribution income totaled $35.5 million — a $1.1 million increase over FY16, God provided. God increased our ministry reach. God paved the way for truly despite the immense loss of the illumiNations 2016 gathering. unprecedented partnership. And God steered us through difficulty where there seemed to be no good way through. A New Day in Nigeria During all of FY17, we watched God shepherd Seed Company through innovation, In the first and second quarter of FY17, a series of unfortunate events led Seed Company to dissolve its partnership with a long-term partner in Africa. However, acceleration and generosity. We invite you to celebrate with us and focus upon God. from a grievous and very trying situation, God brought redemption that only He could provide. FROM THE PRESIDENT When the dissolution of the partnership was completed, we naturally assumed Seed Company continues our relentless pursuit of Vision 2025. I am reminded we would have to curb our involvement in Africa’s most populous nation, home that the founding board prayerfully and intentionally recorded the very first to more than 500 living languages. God had other plans. board policy: The board directs management to operate Seed Company in an The Lord surprised us. We watched the Lord stir new things into motion for the outcomes-oriented manner. -

American Baptist Foreign Mission

American Baptist Foreign Mission ONE-HUNDRED-NINETEENTH ANNUAL REPORT Presented by the Board o f Managers at the Annual Meeting held in W ashington, D. C., M ay 23-28, 1933 Foreign Mission Headquarters 152- Madison Avenue New York PRINTED BY RUMFORD PRESS CONCORD. N. H. U .S . A - CONTENTS PAGE OFFICERS ................................................................................................................................... 5 GENERAL AGENT, STATE PROMOTION DIRECTORS .................... 6 BY-LAWS ..................................................................................................................................... 7 -9 PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... 11 GENERAL REVIEW OF THE YEAR .................................................................1 5 -5 7 T h e W o r l d S it u a t i o n ................................................................................................ 15 A r m e d C o n f l ic t in t h e F a r E a s t ..................................................................... 16 C iv i l W a r in W e s t C h i n a ...................................................................................... 17 P h il ip p in e I ndependence ....................................................................................... 17 I n d ia ’ s P o l it ic a l P r o g r a m ..................................................................................... 18 B u r m a a n d S e p a r a t i o n ............................................................................................. 18 R ig h t s o f P r o t e s t a n t M is s io n s in B e l g ia n C o n g o ............................... 19 T h e W o r l d D e p r e s s io n a n d M i s s i o n s ........................................................... 21 A P e n t e c o s t A m o n g t h e P w o K a r e n s ........................................................... -

Bibs 218/318

Theology BIBS218/318: Judaism in the Time of Jesus Course Outline BIBS 218/318 Judaism in the Time of Jesus Campus Course Outline 2020 SEMESTER 2 2020 In this paper, we are going to be looking at the history, literature, beliefs, and practices of Campus lectures: Judaism — or Judaisms — in the Hellenistic, Hasmonaean, and Roman periods, roughly Tuesday 14:00-15:50 from the campaigns of Alexander the Great to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by Lecturer and paper co-ordinator: the Romans in 70 CE (that is, the late Second Temple period). We will also be looking in more Revd Dr James Harding detail at a number of particular texts and [email protected] traditions within both Palestinian and Diaspora (03) 479 5392 Judaism(s) during that period, especially the Dead Sea Scrolls from Qumran and Masada. Teaching fellow: This is the period when the books of the Jordan Chapman Tanakh (Hebrew Bible or Old Testament) were [email protected] finalized, canonized, and first translated, but it is also the period that forms the background to the Jewish traditions alluded to in the New Testament, and to the traditions that developed further in the Rabbinic Literature (Mishnah, Tosefta, Talmudim, Targumim, and Midrashim). A sound knowledge of this period, and of the texts and traditions that originated then, is essential to a sound understanding of the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and the literature of the later Rabbis of the tannaitic and amoraic periods. We will be asking: what did it mean to identify oneself, or -

The Development of the Wycliffe Bible Translators and the Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1934-1982

The Development of the Wycliffe Bible Translators and the Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1934-1982 Fredrick A. Aldridge Jr Department of History and Politics School of Arts and Humanities University of Stirling A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervised by Professor David W. Bebbington 28 November 2012 I, Fredrick A. Aldridge Jr, declare that this thesis has been composed by me and that the work which it embodies is my work and has not been included in another thesis. ii Acknowledgements In the course of researching and writing this thesis I benefited from the assistance of a long list of Wycliffe Bible Translators (WBT) and SIL International (SIL) (formerly the Summer Institute of Linguistics) members, all of whom generously gave of their time and candidly shared their experiences. To Tom Headland goes particular appreciation for his encouragement, provision of obscure documents and many hours of answering inquisitive questions. Likewise I am indebted to Cal Hibbard, the archivist for the Townsend Archives, for his help on numerous occasions. Cal’s labours to collect, organize and preserve Townsend’s voluminous correspondence over the past several decades has rendered to historians a veritable goldmine. I also wish to thank WBT and SIL for granting me an extended study leave to pursue this research project. And I am especially grateful to WBT and SIL for the complete and unfettered access to the organization’s archives and for permitting me the freedom to research the development of the organization wherever the sources led. The staff and faculty at the University of Stirling were ever helpful. -

Week 1 What Is the Bible Handout

The Gospel of Matthew Week 1: What Is the Bible? What is the Bible? ❖ Old Testament or Hebrew Bible: 39 books, creation of the world through Israel’s return from exile; contains Pentateuch, wisdom writings including Psalms and Proverbs, histories, prophets; written in Hebrew ❖ New Testament: 27 books, life of Jesus through first two centuries of Christianity; contains gospels, Acts of the Apostles, letters, Revelation; written in Greek ❖ Apocrypha: additions to the Old Testament, written after Old Testament times; mostly written in Greek; no consensus within Christianity on whether the Apocrypha are in the Bible or not, Anglicanism regards 15 books as authoritative for teaching but not for doctrine ❖ Bible has to be translated, which is an interpretive act; Erasmus on baptism: in the water or with the water? ❖ Most common translation in the Episcopal Church is the New Revised Standard Version ❖ If you buy a Bible, choose a study Bible with explanatory essays and footnotes that includes the Apocrypha; New Oxford Annotated Bible and Harper Collins Study Bible are both New Revised Standard Version, also Common English Study Bible What is the Bible from a faith perspective? ❖ BCP Catechism, 853: “The Old Testament consists of books written by the people of the Old Covenant, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, to show God at work in nature and history….The New Testament consists of books written by the people of the New Covenant, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, to set forth the life and teachings of Jesus and to proclaim the