Words of Wisdom the Principles, Methods and Essential Knowledge of Chess by Mike Henebry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Combinatorial Game Theoretic Analysis of Chess Endgames

A COMBINATORIAL GAME THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF CHESS ENDGAMES QINGYUN WU, FRANK YU,¨ MICHAEL LANDRY 1. Abstract In this paper, we attempt to analyze Chess endgames using combinatorial game theory. This is a challenge, because much of combinatorial game theory applies only to games under normal play, in which players move according to a set of rules that define the game, and the last player to move wins. A game of Chess ends either in a draw (as in the game above) or when one of the players achieves checkmate. As such, the game of chess does not immediately lend itself to this type of analysis. However, we found that when we redefined certain aspects of chess, there were useful applications of the theory. (Note: We assume the reader has a knowledge of the rules of Chess prior to reading. Also, we will associate Left with white and Right with black). We first look at positions of chess involving only pawns and no kings. We treat these as combinatorial games under normal play, but with the modification that creating a passed pawn is also a win; the assumption is that promoting a pawn will ultimately lead to checkmate. Just using pawns, we have found chess positions that are equal to the games 0, 1, 2, ?, ", #, and Tiny 1. Next, we bring kings onto the chessboard and construct positions that act as game sums of the numbers and infinitesimals we found. The point is that these carefully constructed positions are games of chess played according to the rules of chess that act like sums of combinatorial games under normal play. -

Little Chess Evaluation Compendium by Lyudmil Tsvetkov, Sofia, Bulgaria

Little Chess Evaluation Compendium By Lyudmil Tsvetkov, Sofia, Bulgaria Version from 2012, an update to an original version first released in 2010 The purpose will be to give a fairly precise evaluation for all the most important terms. Some authors might find some interesting ideas. For abbreviations, p will mean pawns, cp – centipawns, if the number is not indicated it will be centipawns, mps - millipawns; b – bishop, n – knight, k- king, q – queen and r –rook. Also b will mean black and w – white. We will assume that the bishop value is 3ps, knight value – 3ps, rook value – 4.5 ps and queen value – 9ps. In brackets I will be giving purely speculative numbers for possible Elo increase if a specific function is implemented (only for the functions that might not be generally implemented). The exposition will be split in 3 parts, reflecting that opening, middlegame and endgame are very different from one another. The essence of chess in two words Chess is a game of capturing. This is the single most important thing worth considering. But in order to be able to capture well, you should consider a variety of other specific rules. The more rules you consider, the better you will be able to capture. If you consider 10 rules, you will be able to capture. If you consider 100 rules, you will be able to capture in a sufficiently good way. If you consider 1000 rules, you will be able to capture in an excellent way. The philosophy of chess Chess is a game of correlation, and not a game of fixed values. -

Ebook Download Chess for Everyone: a Complete Guide for the Beginner

CHESS FOR EVERYONE: A COMPLETE GUIDE FOR THE BEGINNER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert M Snyder | 205 pages | 30 Dec 2008 | iUniverse | 9780595482061 | English | Bloomington IN, United States Chess for Everyone: A Complete Guide for the Beginner PDF Book The antithesis of the defensive principle: strive to separate the King and Knight, know the winning maneuvers. White to play wins, whereas black to play is a draw This is in accordance to the principle of Rook passiveness. In some cases, on-site registration might not be offered at all! About Simon Pavlenko. Another complicated maneuver which requires white to make the best of his Knight-Bishop duo. Doubled pawns are a liability, but when your opponent has none, they can be a good thing. Balance action with reflection. Return to Book Page. Design Co. Once you learn the game you can move on to playing chess online. If you're buying a used kiln, check for obvious damage, such as cracks in the metal broken fire- bricks and damage to the heating elements. We list them for you and discuss their success. Before you move into those specialized techniques and strategies, however, you do need to have a complete understanding of the opening phase. You are basically trusting some anonymous VPN company not to impliment a man-in-the-middle attack on you. Kiln size is another consideration. How many other guides explain the actually playing environment? Not only does it give you the basic tactics and strategy but it also outlines the rules you need to win. Filed to: VPN Services. -

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 5 Preface 6 Introduction 9 1 Glossary of Attacking and Strategic Terms 11 2 Double Attack 23 2.1: Double Attacks with Queens and Rooks 24 2.2: Bishop Forks 31 2.3: Knight Forks 34 2.4: The Í+Ì Connection 44 2.5: Pawn Forks 45 2.6: The Discovered Double Attack 46 2.7: Another Type of Double Attack 53 Exercises 55 Solutions 61 3 The Role of the Pawns 65 3.1: Pawn Promotion 65 3.2: The Far-Advanced Passed Pawn 71 3.3: Connected Passed Pawns 85 3.4: The Pawn-Wedge 89 3.5: Passive Sacrifices 91 3.6: The Kamikaze Pawn 92 Exercises 99 Solutions 103 4 Attacking the Castled Position 106 4.1: Weakness in the Castled Position 106 4.2: Rooks and Files 112 4.3: The Greek Gift 128 4.4: Other Bishop Sacrifices 133 4.5: Panic on the Long Diagonal 143 4.6: The Knight Sacrifice 150 4.7: The Exchange Sacrifice 162 4.8: The Queen Sacrifice 172 Exercises 176 Solutions 181 5 Drawing Combinations 186 5.1: Perpetual Check 186 5.2: Repetition of Position 194 5.3: Stalemate 197 5.4: Fortress and Blockade 202 5.5: Positional Draws 204 Exercises 207 Solutions 210 6 Combined Tactical Themes 213 6.1: Material, Endings, Zugzwang 214 6.2: One Sacrifice after Another 232 6.3: Extraordinary Combinations 242 6.4: A Diabolical Position 257 Exercises 260 Solutions 264 7 Opening Disasters 268 7.1: Open Games 268 7.2: Semi-Open Games 274 7.3: Closed Games 288 8 Tactical Examination 304 Test 1 306 Test 2 308 Test 3 310 Test 4 312 Test 5 314 Test 6 316 Hints 318 Solutions 320 Index of Names 331 Index of Openings 335 THE ROLE OF THE PAWNS 3 The Role of the Pawns Ever since the distant days of the 18th century 3.1: Pawn Promotion (let us call it the time of the French Revolution, or of François-André Danican Philidor) we have known that “pawns are the soul of chess”. -

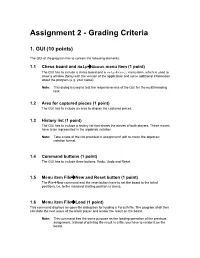

Assignment2 Grading Criteria

Assignment 2 - Grading Criteria 1. GUI (10 points) The GUI of the program has to contain the following elements: 1.1 Chess board and HelpÆAbout menu item (1 point) The GUI has to include a chess board and a HelpÆAbout menu item, which is used to show a window (form) with the version of the application and some additional information about the program (e.g. your name). Note: This dialog is used to test the responsiveness of the GUI for the multithreading task. 1.2 Area for captured pieces (1 point) The GUI has to include an area to display the captured pieces. 1.3 History list (1 point) The GUI has to include a history list that shows the moves of both players. These moves have to be represented in the algebraic notation. Note: Take a look at the link provided in assignment1.pdf to check the algebraic notation format. 1.4 Command buttons (1 point) The GUI has to include three buttons: Redo, Undo and Reset. 1.5 Menu item FileÆNew and Reset button (1 point) The FileÆNew command and the reset button have to set the board to the initial positions. I.e. to the standard starting position in chess. 1.6 Menu item FileÆLoad (1 point) This command displays an open-file dialog box for loading a Forsyth file. The program shall then calculate the next move of the black player and render the result on the board. Note: This command has the same purpose as the loading operation of the previous assignment. Instead of printing the result in a file, you have to render it on the board. -

MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City by Norman Davies (Pp

communicated his desire to the Bishop, in inimitable fashion: MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City by Norman Davies (pp. 224-266) The Holy Ghost and I are agreed that Prelate Schaffgotsch should be coadjutor of [Bresslau] and that those of your canons who resist him shall be regarded as persons who have surrendered to the Court in Vienna and to the Devil, and, having resisted the Holy Prussia annexed Silesia in the early phase of the Enlightenment. Europe was Ghost, deserve the highest degree of damnation. turning its back on the religious bigotry of the preceding period and was entering the so-called 'Age of Reason'. What is more, Prussia was one of the The Bishop replied in kind: more tolerant of the German states. It did not permit the same degree of religious liberty that had been practised in neighbouring Poland until the late The great understanding between the Holy Ghost and Your Majesty is news to me; I was seventeenth century, but equally it did not profess the same sort of religious unaware that the acquaintance had been made. I hope that He will send the Pope and the partisanship that surrounded the Habsburgs. The Hohenzollerns of Berlin had canons the inspiration appropriate to our wishes. welcomed Huguenot refugees from France and had found a modus vivendi between Lutherans and Calvinists. In this case, the King was unsuccessful. A compromise solution had to be Yet religious life in Prussian Silesia would not lack controversy. The found whereby the papal nuncio in Warsaw was charged with Silesian affairs. annexation of a predominantly Catholic province by a predominantly But, in 1747, the King tried again and Schaffgotsch, aged only thirty-one, was Protestant kingdom was to bring special problems. -

Chess Horizons

FREE ENTRY FOR GMs & IMs 78th New England Open September 1 – 3, 2018 Location: Crowne Plaza Boston - Newton 20 USCF 320 Washington St. Grand Prix 3‐day and 2‐day options available! Newton, MA 02458 Points Prizes: $4,000 b/120 paid entries, 75% guaranteed Championship $650 – 300 – 250, top U2400 $225, top U2200 $225 U2000 $400 – 200 – 150 U1800 $400 – 200 – 150 U1600 $300 – 150 – 100, top U1400 $150, top U1200 $150 Time Control: 40/100, SD/30 d10 (2‐day rounds 1‐3 are G/45 d5) Sections: Championship Section (rated 1800+) – 3‐day only – FIDE Rated U2000 Section – 3‐day or 2‐day U1800 Section – 3‐day or 2‐day U1600 Section – 3‐day or 2‐day Round Times: 3‐day section – Saturday 11 AM & 5 PM, Sunday 11 AM & 5 PM, Monday 10 AM & 3: 5 PM 2‐day section – Sunday 1 : 0 AM, 1: 0 PM, : 0 PM, & 5 PM; Monday 10 AM & 3: 5 PM :00 :30 :00 :30 :30 4 Byes: Limit 2 byes, rounds 1‐5 in1 0 Championship Section, rounds 1‐6 in0 3 0 :30 U2000:30 to U16004 sections. Players must commit to byes in rounds 4‐6 before round 2. Entry Fee: Byes in rounds 4-6 are irrevocable. 3‐day section ‐ $75 online by 11:59 PM on 8/3 , $85 onsite 2‐day section ‐ $74 online by 11:59 PM on 8/3 , $85 onsite 0 Onsite Registration: 3‐day – Saturday 9/ from 8:0 30 to 9:30 AM; 2‐day – Sunday 9/ from 8:30 to 9:30 AM Other Information: 1 2 ‐ There is no 2‐day schedule for the Championship Section. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

3 After the Tournament

Important Dates for 2018-19 Important Changes early Sept. Chess Manual & Rule Book posted online TERMS & CONDITIONS November 1 Preliminary list of entries posted online V-E-3 Removes all restrictions on pairing teams at the state December 1 Official Entry due tournament. The result will be that teams from the same Official Entry should be submitted online by conference may be paired in any round. your school’s official representative. V- E-6 Provides that sectional tournament will only be paired There is no entry fee, but late entries will incur after registration is complete so that last-minute with- a $100 late fee. drawals can be taken into account. December 1 Updated list of entries posted online IX-G-4 Clarifies that the use of a smartwatch by a player is ille- gal, with penalties similar to the use of a cell phone. December 1 List of Participants form available online Contact your activities director for your login ID and password. VII-C-1,4,5,6 and VIII-D-1,2,4 Failure to fill out this form by the deadline con- Eliminates individual awards at all levels of the stitutes withdrawal from the tournament. tournament. Eliminates the requirement that a player stay on one board for the entire tournament. Allows January 2 Required rules video posted players to shift up and down to a different board, while January 16 Deadline to view online rules presentation remaining in the "Strength Order" declared by the Deadline to submit List of Participants (final coach prior to the start of the tournament. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

Aims: to Enable Participants to Teach Young and Gifted Players in Schools

FIDE Trainers’ Seminar for FIDE Trainer Titles 1. Objective: To educate and certify Trainers and Chess-Teachers on an international basis. This FIDE Trainers’ Seminar for FIDE Trainer Titles Diploma is approved by FIDE and the FIDE Trainers’ Commission (TRG). The seminar is co-organised by the FIDE, the European Chess Union (ECU), the FIDE Trainers’ Commission (TRG), the Russian Chess Federation and the Russian Chess Academy. 2. Dates: 8th October to 13th October 2013. 3. Location: Moscow, Russia. 4. Participants - Qualification / Professional Skills Requirements: FIDE/TRG will award the following titles, according to the approved TRG Guide: 1.2. Titles’ Descriptions / Requirements / Awards: 1.2.2. FIDE Trainer (FT) 1.2.2.1. Scope / Mission: a. Boost international level players in achieving playing strengths of up to FIDE ELO rating 2450. b. National examiner. 1.2.2.2. Qualification / Professional Skills Requirements: a. Proof of national trainer education and recommendation for participation by the national federation. b. Proof of at least 5 years activity as a trainer. c. Achieved a career top FIDE ELO rating of 2300 (strength). d. TRG seminar norm. 1.2.2.3. Title Award: a. By successful participation in a TRG Seminar. b. By failing to achieve the FST title (rejected application). 1.2.3. FIDE Instructor (FI) 1.2.3.1. Scope / Mission: a. Raised the competitive standard of national youth players to an international level. b. National examiner. c. Trained players with rating below 2000. FIDE Trainers’ Seminar - Moscow 2013 1 1.2.3.2. Qualification / Professional Skills Requirements: a. Proof of national trainer education and recommendation for participation by the national federation. -

This Multi-Media Resource List, Compiled by Gina Blume Of

Delve Deeper into Brooklyn Castle A film by Katie Dellamaggiore This list of fiction and Lost Generation-- and What Eight-time National Chess nonfiction books, compiled We Can Do About It. New Champion as a youth and by Erica Bess, Susan Conlon York: Harper Perennial, subject of the film Searching for and Hanna Lee of Princeton 2013. Froymovich discusses the Bobby Fischer (1993), Josh Public Library, provides a impact of the 2008 recession on Waitzkin later expanded his range of perspectives on the millennials (defined as people horizons and studied martial issues raised by the POV being born between 1976 and arts, eventually earning several documentary Brooklyn 2000) and presents ideas such National and World Castle. as political activism and creative Championship titles. In this entrepreneurship as potential book, he shares his personal Brooklyn’s I.S. 318, a solutions to the long-term side journey to the top—twice—and powerhouse in junior high chess effects of financial crisis. his reflections on principles of competitions, has won more learning and performance. than 30 national championships, Kozol, Jonathan. Savage the most of any school in the Inequalities: Children in Weinreb, Michael. The Kings country. Its 85-member squad America’s Schools. New of New York: A Year Among boasts so many strong players York: Crown, 1991. National the Geeks, Oddballs, and that the late Albert Einstein, a Book Award-winning author Geniuses Who Make Up dedicated chess maven, would Jonathan Kozol presents his America’s Top High School rank fourth if he were on the shocking account of the Chess Team.