Dutch Polder System 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dutch Landscape Painting: Documenting Globalization and Environmental Imagination Irene J

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Proceedings from the Document Academy University of Akron Press Managed December 2014 Dutch Landscape Painting: Documenting Globalization and Environmental Imagination Irene J. Klaver University of North Texas, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/docam Part of the Dutch Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Klaver, Irene J. (2014) "Dutch Landscape Painting: Documenting Globalization and Environmental Imagination," Proceedings from the Document Academy: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.35492/docam/1/1/12 Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/docam/vol1/iss1/12 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by University of Akron Press Managed at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings from the Document Academy by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Klaver: Dutch Landscape Painting A passport is often considered the defining document of one’s nationality. After more than twenty years of living in the United States, I still carry my Dutch passport. It still feels premature for me to give it up and become an American. When people ask, “Where are you from?” I answer, “Denton, Texas.” This usually triggers, “OK, but where are you FROM???” It is the accent that apparently documents my otherness. -

Rootsmagic Document

First Generation 1. Geert Somsen1 was born about 1666 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. He died about 1730 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. He has a reference number of [P272]. (Boeinck), ook wel: Sumps. Geert werd op 24-06-1686 (Sint Jan) ingeschreven als lidmaat van de Nederduits Gereformeerde Gemeente Aalten [Boeinck (also: Sumps). Geert was admitted as a member of the Dutch Reformed Church of Aalten on 24-06-1686 (St. John)]. Geert Somsen and Mechtelt Gelkinck had marriage banns published on 28 Apr 1689 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. They were married on 27 May 1689 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. Mechtelt Gelkinck1 (daughter of Roelof Somsen and Geesken Rensen) was born before 25 Aug 1662 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. 2 She was christened on 25 Aug 1662 in Dinxperlo, GE, Netherlands.2 She died in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. She has a reference number of [P273]. ook wel: Meghtelt. Also: Sumps. op 29-09-1688 werd Mechtelt als lidmaat v.d. Nederduits Geref. Ge,. Aalten ingeschreven [also: Meghtelt. Also: Sumps. On 29 Sep 1688 she was registered as Mechtelt as a member of the Dutch Reformed Church in Aalten]. Geert Somsen and Mechtelt Gelkinck had the following children: +2 i. Jantjen Somsen (born on 9 Nov 1690). +3 ii. Roelof Somsen (born about 1692). +4 iii. Geesken Somsen (born in 1695). +5 iv. Wander Somsen (born on 9 Jul 1699). +6 v. Frerik Somsen (born about Jan 1703). Second Generation 2. Jantjen Somsen1 (Geert-1) was born on 9 Nov 1690 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. She died on 15 Sep 1767 in Dinxperlo, GE, Netherlands. -

TU1206 COST Sub-Urban WG1 Report I

Sub-Urban COST is supported by the EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020 Rotterdam TU1206-WG1-013 TU1206 COST Sub-Urban WG1 Report I. van Campenhout, K de Vette, J. Schokker & M van der Meulen Sub-Urban COST is supported by the EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020 COST TU1206 Sub-Urban Report TU1206-WG1-013 Published March 2016 Authors: I. van Campenhout, K de Vette, J. Schokker & M van der Meulen Editors: Ola M. Sæther and Achim A. Beylich (NGU) Layout: Guri V. Ganerød (NGU) COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) is a pan-European intergovernmental framework. Its mission is to enable break-through scientific and technological developments leading to new concepts and products and thereby contribute to strengthening Europe’s research and innovation capacities. It allows researchers, engineers and scholars to jointly develop their own ideas and take new initiatives across all fields of science and technology, while promoting multi- and interdisciplinary approaches. COST aims at fostering a better integration of less research intensive countries to the knowledge hubs of the European Research Area. The COST Association, an International not-for-profit Association under Belgian Law, integrates all management, governing and administrative functions necessary for the operation of the framework. The COST Association has currently 36 Member Countries. www.cost.eu www.sub-urban.eu www.cost.eu Rotterdam between Cables and Carboniferous City development and its subsurface 04-07-2016 Contents 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................5 -

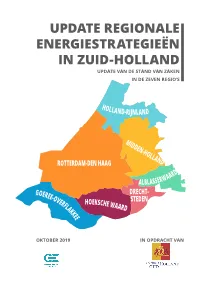

PZH Evaluatie Update RES Rapport

UPDATE REGIONALE IN DE ZEVEN REGIO’S UPDATE VAN DE STAND VAN ZAKEN ENERGIESTRATEGIEËNIN ZUID-HOLLANDD LAN RIJN ND- HOLLA MIDDEN-HOLLAND D R AA W ER SS LA ALB DRECHT- STEDEN ROTTERDAM-DEN HAAG RD E WAA KSCH HOE IN OPDRACHT VAN EREE-OVERFLAK GO KEE OKTOBER 2019 2 1| INLEIDING INLEIDING Dit document is een update van de studie ‘Regionale Energiestrategieeën in Zuid-Holland, analyse en vergelijking van de stand van zaken in de zeven regio’s’, uit augustus 2018. Deze update kijkt dus naar de huidige stand van zaken, in oktober 2019. De provincie Zuid-Holland bestaat uit 7 RES-regio’s; Alblasserwaard, Drechtsteden, Goeree-Overflakkee, Hoeksche Waard, Holland-Rijnland, Midden-Holland, en Rotterdam-Den Haag. Voor de dikgedrukte vier regio’s zijn nieuwe documenten aangeleverd die in de update gebruikt zijn: - Alblasserwaard: BVR-eindrapport (conceptversie) - Alblasserwaard: Res vervolgproces_alblasserwaard - Drechtsteden: transitievisie warmte 1.0 - Holland-Rijnland : Energieakkoord Holland Rijnland 2017-2025, Uitvoeringsprogramma 2019 - Holland-Rijnland: Notitie ‘Van Regionaal Energieakkoord Holland Rijnland naar Regionale Energiestrategie (RES) Holland Rijnland’ - Rotterdam-Den Haag: Energieperspectief 2050 Rotterdam-Den Haag - Rotterdam-Den Haag: Regionale prioriteiten RES De gebruikte bronnen van het rapport van augustus 2018 staan genoemd ‘Regionale Energiestrategieeën in Zuid-Holland, analyse en vergelijking van de stand van zaken in de zeven regio’s’, uit augustus 2018. In deze update is de nadruk gelegd op de regio Rotterdam-Den Haag, Alblasserwaard, Drechtsteden en Holland- Rijnland omdat er voor deze deelregio’s nieuwe documenten ontwikkeld zijn. Voor de overige regio’s zijn er in dit overzichtsdocument geen aanpassingen gedaan. Wel zijn de aangepaste grenzen van de deelregio’s en van de provincie aangepast naar 2019. -

Challenges for the Dutch Polder Model

Challenges for the Dutch polder model ESPN Flash Report 2017/40 FABIAN DEKKER – EUROPEAN SOCIAL POLICY NETWORK JUNE 2017 Description The polder model stands for In the Netherlands, shifts in the good reasons, in the first years, the consensus-oriented relationship between the social partners model was described as “A Dutch consultation can be observed. In 2013, employers’ Miracle”. between the social and employee organisations concluded In the past fifteen years, the Dutch partners. Mainly a social agreement, which, among other consultative model has come under due to the things, included an arrangement to reverse a previously agreed reduction of increasing pressure. Due to reduced increasing flexibility membership numbers, the position of of work and the the maximum duration of unemployment benefits (from 38 to 24 trade unions has dramatically trade unions’ months) and return to a maximum of 38 weakened. In 2015, only one in six declining level of months. Although employers’ employees was a trade union member, organisation, this organisations signed this agreement at as opposed to one in approximately dialogue is losing the time, for a long time they tried to three employees in the 1970s (Keune impact. This is get out of implementing it. Another 2016). This has reduced the particularly visible element observed is the occurrence of organisational power of civil society. In in current debates strikes. While the level of conflict in the addition, support for agreement on unemployment Netherlands is relatively low in general, between the social partners has benefit duration the highest level of strikes in nine years decreased due to changes that have and a number of was recorded in 2015 (CBS 2016). -

Centenary of the Zuiderzee Act: a Masterpiece of Engineering

NEWS Centenary of the Zuiderzee Act: a Masterpiece of Engineering The Dutch Zuiderzee Act came into force exactly 100 years ago today, on 14 June 1918. The Zuiderzee Act signalled the beginning of the works that continue to protect the heart of The Netherlands from the dangers and vagaries of the Zuiderzee, an inlet of the North Sea, to this day. This amazing feat of engineering and spatial planning was a key milestone in The Netherlands’ world-leading reputation for reclaiming land from the sea. Wim van Wegen, content manager at ‘GIM International’, was born, raised and still lives in the Noordoostpolder, one of the various polders that were constructed. He has written an article about the uniqueness of this area of reclaimed land. I was born at the bottom of the sea. Want to fact-check this? Just compare a pre-1940s map of the Netherlands to a more contemporary one. The old map shows an inlet of the North Sea, the Zuiderzee. The new one reveals large parts of the Zuiderzee having been turned into land, actually no longer part of the North Sea. In 1932, a 32km-long dam (the Afsluitdijk) was completed, separating the former Zuiderzee and the North Sea. This part of the sea was turned into a lake, the IJsselmeer (also known as Lake IJssel or Lake Yssel in English). Why 'polder' is a Dutch word The idea behind the construction of the Afsluitdijk was to defend areas against flooding, caused by the force of the open sea. The dam is part of the Zuiderzee Works, a man-made system of dams and dikes, land reclamation and water drainage works. -

Geohydrological Compensatory Measures to Prevent Land Subsidence As a Result of the Reclamation of the Markerwaard Polder in the Netherlands

GEOHYDROLOGICAL COMPENSATORY MEASURES TO PREVENT LAND SUBSIDENCE AS A RESULT OF THE RECLAMATION OF THE MARKERWAARD POLDER IN THE NETHERLANDS. G. Vos , F.A.M. Claessen , J.H.G. van Ommen** Public Works Department, Rijkswaterstaat, Directorate of Water Manage ment and Hydraulic Research, Northern District. International Water Supply Consultants IWACO B.V. ABSTRACT If the Markerwaard polder is reclaimed the water level in the polder will fall 5 to 6 metres over an area of 410 km2. This will cause a drawdown of the piezometric levels in the Pleistocene aquifers underneath the eastern part- of the province of North Holland. The spatial pattern of these drawdowns is calculated by a finite elements groundwater model. Without countermeasures to;compensate for the depletion of the piezometric level, settlement of the compressible Holocene clay and peat deposits will occur and resultant land subsidence may cause damage to buildings and infrastructure. Drawdown of the piezometric levels can be entirely or partially countered by means of artificial recharge of water into the Pleisto cene aquifers. There are two methods for this, viz. vertical recharge wells and infiltration grooves in the remaining western peripheral lake between North Holland and the Markerwaard polder. The amount of water necessary for the countermeasures is calculated with the same groundwater model. 1. INTRODUCTION The study area is situated in the north-western part of the Netherlands (fig. 1). The projected polder will have an area of 410 km2 and will be reclaimed in the south-western part of Lake IJssel. The phreatic groundwater level in the new polder will be some 5 to 6 metres lower than the present water level in Lake IJssel. -

Cultural Policy in the Polder

Cultural Policy in the Polder Cultural Policy in the Polder 25 years of the Dutch Cultural Policy Act Edwin van Meerkerk and Quirijn Lennert van den Hoogen (eds.) Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Koopman & Bolink: Boothuis, Noordoostpolder. Fotografie: Dirk de Zee. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 625 1 e-isbn 978 90 4853 747 1 doi 10.5117/9789462986251 nur 754 | 757 © The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2018 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 9 An Introduction to Cultural Policy in the Polder 11 Edwin van Meerkerk and Quirijn Lennert van den Hoogen A Well-Balanced Cultural Policy 37 An Interview with Minister of Culture Ingrid van Engelshoven Marielle Hendriks 1. Legal Aspects of Cultural Policy 41 Inge van der Vlies 2. An International Perspective on Dutch Cultural Policy 67 Toine Minnaert ‘A Subsidy to Make a Significant Step Upwards’ 85 An Interview with Arjo Klingens André Nuchelmans 3. The Framing Game 89 Towards Deprovincialising Dutch Cultural Policy Johan Kolsteeg1 4. Values in Cultural Policymaking 107 Political Values and Policy Advice Quirijn Lennert van den Hoogen and Florine Jonker An Exercise in Undogmatic Thinking 131 An Interview with Gable Roelofsen Bjorn Schrijen 5. -

Pham Thi Minh Thu

Institut für Wasserwirtschaft und Kulturtechnik Universität Karlsruhe (TH) A Hydrodynamic-Numerical Model of the River Rhine Pham Thi Minh Thu Heft 213 Mitteilungen des Instituts für Wasserwirtschaft und Kulturtechnik der Universität Karlsruhe (TH) mit ″Theodor-Rehbock-Wasserbaulaboratorium″ Herausgeber: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. h. c. Franz Nestmann, Ordinarius 2002 A Hydrodynamic-Numerical Model of the River Rhine Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTOR-INGENIEURS der Fakultät für Bauingenieur- und Vermessungswesen der Universität Fridericiana zu Karlsruhe (TH) genehmigte DISSERTATION von Dipl. -Ing. Pham Thi Minh Thu aus Hanoi, Vietnam Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 13. Februar 2002 Hauptreferent: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. h.c. mult. Franz Nestmann 1. Korreferent: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Helmut Scheuerlein 2. Korreferent: Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Hans Helmut Bernhart Karlsruhe, 2002 Vorwort Der Rhein unterliegt seit Jahrhunderten anthropogenen Eingriffen, die sich auf das Ablaufverhalten von Hochwasserwellen auswirken. Der Schutz und die Wiederherstellung ökologisch funktionsfähiger, naturnaher Gewässer ebenso wie eine bessere Hochwasserregulierung sind wesentliche Aufgaben der Wasserwirtschaft, wobei eine gesamtheitliche Betrachtungsweise erforderlich ist. Um die hydraulischen Auswirkungen einer Rückgewinnung von Retentionsräumen auf Hochwasserereignisse zu quantifizieren, wurde von Frau Dr. Minh Thu in dieser Forschungsarbeit ein hydrodynamisch-numerisches Modell für die gesamte deutsche Teilstrecke des freifließenden Rheins erstellt. Es besteht aus -

Groundwater Impacts on Surface Water Quality and Nutrient Loads in 2 Lowland Polder Catchments: Monitoring the Greater Amsterdam Area

1 Groundwater impacts on surface water quality and nutrient loads in 2 lowland polder catchments: monitoring the greater Amsterdam area 3 Liang Yu1, 2, Joachim Rozemeijer3, Boris M. van Breukelen4, Maarten Ouboter2, Corné van der Vlugt2, 4 Hans Peter Broers5 5 1Faculty of Science, Vrije University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 1181HV, The Netherlands 6 2 Waternet Water Authority, Amsterdam, 1096 AC, The Netherlands 7 3Deltares, Utrecht, 3508 TC, The Netherlands 8 4Department of Water Management, Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Delft University of Technology, 9 Stevinweg 1, 2628 CN Delft, The Netherlands 10 5TNO Geological Survey of The Netherlands, Utrecht, 3584 CB, The Netherlands 11 Correspondence to: Hans Peter Broers ([email protected]) 12 Abstract. The Amsterdam area, a highly manipulated delta area formed by polders and reclaimed lakes, struggles with high 13 nutrient levels in its surface water system. The polders receive spatially and temporally variable amounts of water and 14 nutrients via surface runoff, groundwater seepage, sewer leakage, and via water inlet from upstream polders. Diffuse 15 anthropogenic sources, such as manure and fertilizer use and atmospheric deposition, add to the water quality problems in 16 the polders. The major nutrient sources and pathways have not yet been clarified due to the complex hydrological system in 17 such lowland catchments with both urban and agricultural areas. In this study, the spatial variability of the groundwater 18 seepage impact was identified by exploiting the dense groundwater and surface water monitoring networks in Amsterdam 19 and its surrounding polders. Twenty-five variables (concentrations of Total-N, Total-P, NH4, NO3, HCO3, SO4, Ca, and Cl in 20 surface water and groundwater, N and P agricultural inputs, seepage rate, elevation, land-use, and soil type) for 144 polders 21 were analysed statistically and interpreted in relation to sources, transport mechanisms, and pathways. -

The Tradition of Making Polder Citiesfransje HOOIMEIJER

The Tradition of Making Polder CitiesFRANSJE HOOIMEIJER Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Technische Universiteit Delft, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. ir. K.C.A.M. Luyben, voorzitter van het College voor Promoties, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 18 oktober 2011 om 12.30 uur door Fernande Lucretia HOOIMEIJER doctorandus in kunst- en cultuurwetenschappen geboren te Capelle aan den IJssel Dit proefschrift is goedgekeurd door de promotor: Prof. dr. ir. V.J. Meyer Copromotor: dr. ir. F.H.M. van de Ven Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Rector Magnificus, voorzitter Prof. dr. ir. V.J. Meyer, Technische Universiteit Delft, promotor dr. ir. F.H.M. van de Ven, Technische Universiteit Delft, copromotor Prof. ir. D.F. Sijmons, Technische Universiteit Delft Prof. ir. H.C. Bekkering, Technische Universiteit Delft Prof. dr. P.J.E.M. van Dam, Vrije Universiteit van Amsterdam Prof. dr. ir.-arch. P. Uyttenhove, Universiteit Gent, België Prof. dr. P. Viganò, Università IUAV di Venezia, Italië dr. ir. G.D. Geldof, Danish University of Technology, Denemarken For Juri, August*, Otis & Grietje-Nel 1 Inner City - Chapter 2 2 Waterstad - Chapter 3 3 Waterproject - Chapter 4 4 Blijdorp - Chapter 5a 5 Lage Land - Chapter 5b 6 Ommoord - Chapter 5b 7 Zevenkamp - Chapter 5c 8 Prinsenland - Chapter 5c 9 Nesselande - Chapter 6 10 Zestienhoven - Chapter 6 Content Chapter 1: Polder Cities 5 Introduction 5 Problem Statement, Hypothesis and Method 9 Technological Development as Natural Order 10 Building-Site Preparation 16 Rotterdam -

Geographical Dimensions of Risk Management the Contribution of Spatial Planning and Geo-ICT to Risk Reduction

Geographical Dimensions of Risk Management The contribution of spatial planning and Geo-ICT to risk reduction Johannes Martinus Maria Neuvel Thesis committee Thesis supervisors Prof. dr. ir. A. van den Brink Professor of Integrated Area Development in Metropolitan Landscapes Wageningen University Prof. dr. H.J. Scholten Professor of Spatial Informatics VU University Amsterdam Other members Prof. dr. ir. A.K. Bregt, Wageningen University Prof. dr. B.J.M. Ale, Delft University of Technology Prof. dr. W.G.M. Salet, University of Amsterdam Prof. dr. G. Walker, Lancaster University , United Kingdom This research was conducted under the auspices of the Mansholt Graduate School of Social Sciences Geographical Dimensions of Risk Management The contribution of spatial planning and Geo-ICT to risk reduction Johannes Martinus Maria Neuvel Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Doctorate Board to be defended in public on Wednesday 21 October 2009 at 1:30 PM in the Aula. J.M.M. Neuvel Geographical dimensions of risk management. The contribution of spatial planning and Geo-ICT to risk reduction. 224 pages Thesis Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2009) With references, with summaries in Dutch and English ISBN 978-90-8585-450-0 Preface and Acknowledgements Information is regarded as a crucial ingredient for effective risk management. Since a considerable part of the information required for risk management contains specific spatial references (such as the location of toxic clouds or areas prone to flooding), much attention is paid to the development of geo-information and communications technology (Geo-ICT) to support risk management practices.