Misconceptions in the History of Mancala Games: Antiquity and Ubiquity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mancala: a History

Mancala: A History The name “Mancala” is given to a family of strategy games that are played across the African continent, and which have spread across the globe. It may originally have come from ancient Sumeria. The word “mancala” comes from the Arabic word, “naqala”, which means “to move”. Mancala is essentially a game in which players "sow" and "capture" seeds. This process wasn't always played for fun; in fact, according to some historians, Mancala may have been an ancient record-keeping technique. According to another theory, Mancala originated as a ritual related to the harvest, or may even have been a tool for divination. In some interpretations, the game board represents the world and is best laid in alignment with the rising and setting sun, east to west. The seeds or stones are the stars and the holes are the months of the year. Moving the seeds represents the gods moving through time and space and Mancala predicts our fate. According to some historians, Mancala may have originated with the dawn of civilization. There is limited evidence that the game was played 5,000 years ago in ancient Sumeria (modern day Iraq). The first evidence of the game is a Mancala board from the 4th century AD found in Abu Sha'ar, a late Roman legionary fortress on the Red Sea coast and upper Nile River in Egypt. There is further evidence that Mancala games were played in ancient Egypt before 1400 BCE. Evidence for this theory is available in the form of holes in the ground discovered in Egyptian temples at Tebas, Karnak, and Luxor. -

Algeria Ancestors Angola Animals in African Folklore Arabic Folk Literature of North Africa Architecture Archives of Traditional Music Ashanti Astronomy

A Algeria Ancestors Angola Animals in African Folklore Arabic Folk Literature of North Africa Architecture Archives of Traditional Music Ashanti Astronomy back to top B Bamana Banjo: African Roots Bao Bascom, William Basketry, Africa Basketry, African American Beadwork Benin Birth and Death Rituals among the Gikuyu Blacksmiths: Dar Zaghawa of the Sudan Blacksmiths: Mande of Western Africa Body Arts: African American Arts of the Body Body Arts: Body Decoration in Africa Body Arts: Hair Sculpture Botswana Burkina Faso Burundi back to top C Callaway, Bishop Henry Cameroon Cape Verde Cardinal Directions Caribbean Verbal Arts Carnivals and African American Cultures Cartoons Central African Folklore Central African Republic Ceramics Ceramics and Gender Chad Chief Children's folklore: Iteso Songs of War Time Children's folklore: Kunda Songs Children's Folklore: Ndeble Classiques Africaines Color Symbolism: The Akan of Ghana Comoros Concert Parties Congo (Republic of the Congo) Contemporary Bards: Hausa Verbal Artists Cosmology Cote d'Ivoire Cote d'Ivoire, Folklore Crowley, Daniel back to top D Dance: Overview with a Focus on Namibia Decorated Vehicles (Focus on Western Nigeria) Democratic Republic of Congo Dialogic Performances: Call and Response in African Narrating Diaspora: African Communities in the United Kingdom Diaspora: African Communities in the United States Diaspora: African Traditions in Brazil Diaspora: Sea Islands of the USA Dilemma Tales Divination: Household Divination Among the Kongo Divination: Ifá Divination in Cuba Divination: Overview Djibouti Dolls and Toys Drama: Anang Ibibio Traditional Drama Draughts Dreams Dress Drumming: Ewe Dyula back to top E East African Folklore: Overview Education: Folklore in Schools Egypt Electronic Media and Oral Traditions Epics: Liongo Epic of the Swahili Epics: Overview Epics: West African Epics Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Eshu, the Yoruba Trickster Esthetics: Baule Visual Arts Ethiopia Evans-Pritchard, E. -

Mancala Notes

MANCALA Mancala is a name given to a large family of “ Pit and Seeds ” or “ Count, Sow and Capture ” games -- one of the oldest games known! Mancala games have been played the longest and most popular in Africa, though various versions are played all over the world. Boards have been found dating back to 1400 B.C in Eygpt. By 600 A.D. the game had spread to the Middle East and Asia. Surprisingly, the game was little known in Europe until the 19 th Century. In some parts of Africa. Mancala was reserved for royalty and people of rank, and play was limited to the men, or to particular seasons of the year, or to day time. Women had more important chores to do! The name, “Mancala, ” comes from the Arabic word meaning “ to move. ” Names of various games may refer to the board, or the seeds, or manners of play in native languages. Depending on the culture, pieces are “seeds” or “cows.” These two player games are played with a board, usually consisting of two or four equal rows of cup-shaped Pits that may be carved out of wood or stone, or even just dug out of the dirt. The row or rows on each player’s side belong to that player. Sometimes there is also a larger cup-shaped Storehouse for each player on his right side of the board. Several three row games have been found in Northeastern Africa, and modern inventers have even created a one row board with simultaneous play. The playing pieces may be large seeds, pebbles , or marbles , and they belong to a player only when they are in his row of pits. -

A Presentation of the Mancala Games

MANCALA Is actually a large family of “Pit and Seeds ” or “Count, Sow and Capture ” games Description The Mancala games are some of the oldest games known! Boards have been found carved into stone dating back to 1400 B.C in Egypt. •By 600 A.D. the game had spread to the Middle East and Asia. •Surprisingly, the game was little known in Europe until the 19 th Century. •Mancala games have been played the longest in Africa where they are the most popular, though various versions are played all over the world. •The name “Mancala” actually comes from the Arabic word meaning “To Move” •Mancala games have hundreds of names and many versions. Where in the World do they Play Mancala? 300 Names ??? Adi Andada Aweet Ayoayo Ba-awa Bao Kiarabu Baré Bulto Bao la Kiswahili Cela Chisolo Coro Cuba Dabuda Deka Elee Embeli En Dodoi Fifanga Gamacha Hus Igisoro Isafuba Isolo J'odu Kabwenga Kale Kanona Kâra Katra Kiela Ki- Nyamwezi Kiothi Kisolo Kisoro Kisumbi Kpo Krur Lamlameta Layli Leka Li'b Lubasi Lusolo Mangala Mangura Mbangbi Mbele Mbothe Mefuvha Msuwa Mulabalaba Mwambulula Nakabili Ncaya Nchuwa Ndebukya Ngikilees Njombwa Nsumbi Num-Num Oce Omweso Otu Oware Pereauni Qelat Ruhesho Sadéqa Shayo Soro Spreta Tapata Tchadji Tchouba Tihbat Tok Kurou Tokoro Uera Um el Bagara Um el Banat Usolo Wouri Yit ............And that is just some of Them !!! Customs In some parts of Africa, Mancala was reserved for royalty and people of rank, and play was limited to the men, or to particular seasons of the year, or to day time. -

“Skywatchers of Africa”

Teacher’s Guide to . “SKYWATCHERS OF AFRICA” Objectives: Students/visitors should be able to: • Express an interest in observing many of the same phenomena that were observed by different African people. • Recognize that different African groups used celestial objects and cycles as one of the many ways to organize, and to ensure the survival of, their cultures. • Identify some celestial objects or groupings of stars important to different African cultures (e.g. Sun, Moon, stars, & constellations). • Identify aspects of celestial observations that can be applied to the student’s own lives (e.g. dark sky, changing rise/set positions of the Sun, marking the sunset, etc) • Articulate an appreciation for the sky knowledge of African cultures. This program is aligned with the following Illinois Education Standards: 12.F.2a, 12.F.2b, 12.F.2c, 12.F.4a, 13.B.3b, 13.B.3c, 13.B.5e, 18.C.4a. Next Generation Science Standards: 1.ESS1.1, 1.ESS1.2, 5.ESS1.2 Brief Summary: “Skywatchers of Africa” is a unique program that celebrates the many diverse African cultures (including the Egyptians) and their observations and explanations of the yearly cycles of the heavens. The program discusses the seasons and the changing sunrise/sunset positions and how Africans marked these positions to form a makeshift calendar. Africa has many vibrant cultures thriving today as well as countless past civilizations that continue to speak to us through their sky lore. The program is intended for students in grade 5 or older. This show is made possible by a generous grant from the Staples Foundation. -

1 an Understanding of Socially-Constructed Knowledge in the Context of Traditional Game-Playing As Theorems-In-Action Uma Compre

ARTIGO http://dx.doi.org/10.47207/rbem.v1i0.9237 An Understanding of Socially-Constructed Knowledge in the Context of Traditional Game-Playing as Theorems-in-Action BRAZ DIAS, Ana Lúcia Central Michigan University (CMU). Ph.D. in Mathematics Education from Indiana University. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0674-0758. E-mail: [email protected] BRAZ DIAS, Juliana Universidade de Brasília (UnB). Associate researcher at Stellenbosch University (SUN) and University of Cape Town (UCT). Coordinator of the Laboratório de Etnologia em Contextos Africanos (ECOA/PPGAS/UnB). Ph.D. in Social Anthropology from Universidade de Brasília (UnB). Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0316- 971X. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: In this article the authors describe data from an ethnographical study about the playing of Uril, a mancala-type game played in the island of São Vicente, Cape Verde. They interpret observed game strategies as theorems-in-actions, constructed socially and throughout a long period of time, influenced by socially shared norms and beliefs, as well as by knowledge construction at the 1 individual level. The authors also use knowledge obtained from a computer-generated database to explore a sequence of game moves observed ethnographically, verifying its robustness and the necessary conditions that make it a winning strategy. The authors use evidence from ethnographical data to argue that those necessary conditions are tacitly assumed by the players observed. Keywords: Ethnomathematics. Sowing games. Theorems-in-action. Capeverdean culture. Uma Compreensão do Conhecimento Socialmente Construído no Contexto de um Jogo Tradicional como Teoremas-em-Ação Resumo: Neste artigo, as autoras descrevem dados de um estudo etnográfico sobre o jogo de Uril, um jogo tipo mancala jogado na ilha de São Vicente, Cabo Verde. -

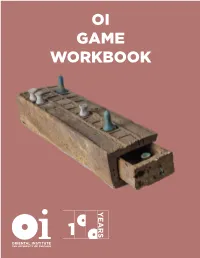

Oi Game Workbook

OI GAME WORKBOOK OI VIRTUAL SCAVENGER HUNT For the past few days we have been exploring games and the ancient world, including contemporary twists on the ancient world in game-play. In the spirit of games and activities, we just had to create a workbook to go along with this week’s theme. Our first activity includes a game-related scavenger hunt on our online database! The rules are simple, go to https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/ and type the provided registration codes (i.e. E26004) in the search bar. From there you will be able to access images, information, and related publications to the selected artifacts – you can even do an “off the books” search of your own and learn more about other objects, publications, and archival photographs in our collection! What is the name of this game? HINT: It is four words, and one of those words is a number! A22254A What site in Egypt is this Game of 20 Squares acacia board from? E371B What period is this game board from? E16950 Queen Nefertari (ca. 1279–1213 BC) playing senet against an invisible opponent Satirical papyrus showing an antelope and a lion, probably playing senet, (1250-1150 BC) Make and Play Your Own Mancala Game! Make an Egg- 2. To make the 4. Tape the mancalas to mancalas—the two the ends of the carton. Carton Mancala “bowls” on either Place four counters in Board end of the board— each cup, and you are cut off each end of ready to begin! You will need: the carton top and two pieces from the • 1 egg carton middle, as shown • 48 beans, coins, below. -

Traditional Cosmological Symbolism in Ancient Board Games

Traditional Cosmological Symbolism in Ancient Board Games Gaspar Pujol Nicolau ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. En la utilización o cita de partes de la tesis es obligado indicar el nombre de la persona autora. -

Africa Ringmar, Erik

Africa Ringmar, Erik Published in: History of International Relations 2016 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Ringmar, E. (2016). Africa. Manuscript submitted for publication. In History of International Relations Open Book Publishers. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Lund, Sweden, March 18, 2016. Dear reader, This is a first draft of the chapter on Africa for the textbook on the history of international relations that I'm working on. I have never been and will never be an expert on Africa and I very much need your help. Could you please let me know 1) what I'm getting wrong; 2) what I should have mentioned. -

The Discovery of Mancala Games in Dhofar, Sultanate of Oman Vincent Charpentier, Alex De Voogt, Rémy Crassard, Jean‑François Berger, Federico Borgi, Ali Al-Mashani

Games on the seashore of Salalah: the discovery of mancala games in Dhofar, Sultanate of Oman Vincent Charpentier, Alex de Voogt, Rémy Crassard, Jean‑françois Berger, Federico Borgi, Ali Al-Mashani To cite this version: Vincent Charpentier, Alex de Voogt, Rémy Crassard, Jean‑françois Berger, Federico Borgi, et al.. Games on the seashore of Salalah: the discovery of mancala games in Dhofar, Sultanate of Oman. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy, Wiley, 2014, 25 (1), pp.115-120. 10.1111/aae.12040. hal- 01828888 HAL Id: hal-01828888 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01828888 Submitted on 4 Jul 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arab. arch. epig. 2014: 25: 115–120 (2014) Printed in Singapore. All rights reserved Games on the seashore of Salalah: the discovery of mancala games in Dhofar, Sultanate of Oman During the 2013 fieldwork of the French archaeological mission along the shores of Vincent Charpentier1 the Arabian Sea, mancala games were discovered on the seashore of Salalah at the site Alex de Voogt2,Remy of Ad-Dahariz. They are cup-hole carvings made directly into rock slabs and distrib- Crassard3, Jean-Francßois uted in six distinct zones of the site. -

PRESS RELEASE Permanent Exhibition The

PRESS RELEASE Permanent Exhibition The Archives of Human Diversity From 1 November 2014 “The Archives of Human Diversity” would be a very appropriate title for the objects selected for the MEG collection’s permanent exhibition, whose scenography has been arranged by Atelier Brückner (Stuttgart). The exhibition encompasses several centuries of history and comprises around one hundred civilisations represented by over one thousand remarkable pieces: objects of reference, historical objects, and works of art all attest to the human potential for creativity. Ange Leccia’s video Sea gives the permanent collection its rhythm. The exhibition itinerary comprises seven main sections: a prologue that focuses on the provenance of the collections, a section devoted to each of the five continents, and an area that focuses on ethnomusicology. The preparation of this permanent exhibition has brought to light hidden treasures that have sometimes been forgotten for generations. For instance, the Ming rhinoceros horn cup, which was donated to the Geneva Public Library’s cabinet of curiosities in 1758, was “hidden” in the MEG’s African collection. And a box from the Marquesas Islands — only the thirteenth known example in the world, which was acquired in 1874 by the Archaeological Museum, had found its way into a Polar Arctic Circle collection. Also revealed are Iroquois objects — a mask and a rattle from the False Face Society, the most ancient acquired by a museum, in 1825.The adoption of a historical approach aims primarily to illustrate the evolution of European perceptions of exotic cultures and to examine the changes in status conferred on objects in the various museums that preceded the MEG in Geneva. -

Black History Month Activity Bag

Black History Month Activity Bag Kente Cloth Coloring Sheets Includes coloring page with DIY photo frame, crayons Watch this video to learn how to make a 3-D paper photo frame! Learn about the significance of colors and patterns in woven Kente cloth from the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art before coloring your own design: Kente cloth is a Ghanaian woven textile worn contemporarily throughout the African Diaspora to commemorate special occasions such as graduations and weddings. Kente comes from the word kenten, which means "basket" in the Asante dialect of Akan language, referencing its basket-like pattern. Colors and patterns in Kente cloth are intentionally selected by the weaver to convey a message. Each color has a significance in the tradition of Kente weaving: • black: maturation, intensified spiritual energy, spirits of ancestors, passing rites, mourning, and funerals • blue: peacefulness, harmony, and love • green: vegetation, planting, harvesting, growth, spiritual renewal • gold: royalty, wealth, high status, glory, spiritual purity • grey: healing and cleansing rituals; associated with ash • maroon: the color of mother earth; associated with healing • pink: associated with the female essence of life; a mild, gentle aspect of red • purple: associated with feminine aspects of life; usually worn by women • red: political and spiritual moods; bloodshed; sacrificial rites and death. • silver: serenity, purity, joy; associated with the moon • white: purification, sanctification rites and festive occasions • yellow: preciousness, royalty, wealth, fertility, beauty Cowrie Shell Bracelet Learn about the significance of cowrie shells from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture before making your own cowrie shell bracelet: Cowrie shells were traded for goods and services throughout Africa, Asia, Europe, and Oceania, and used as money as early as the 14th century on Africa’s western coast.