PRESS RELEASE Permanent Exhibition The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Born of Clay Ceramics from the National Museum of The

bornclay of ceramics from the National Museum of the American Indian NMAI EDITIONS NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON AND NEW YORk In partnership with Native peoples and first edition cover: Maya tripod bowl depicting a their allies, the National Museum of 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 bird, a.d. 1–650. campeche, Mexico. the American Indian fosters a richer Modeled and painted (pre- and shared human experience through a library of congress cataloging-in- postfiring) ceramic, 3.75 by 13.75 in. more informed understanding of Publication data 24/7762. Photo by ernest amoroso. Native peoples. Born of clay : ceramics from the National Museum of the american late Mississippian globular bottle, head of Publications, NMai: indian / by ramiro Matos ... [et a.d. 1450–1600. rose Place, cross terence Winch al.].— 1st ed. county, arkansas. Modeled and editors: holly stewart p. cm. incised ceramic, 8.5 by 8.75 in. and amy Pickworth 17/4224. Photo by Walter larrimore. designers: ISBN:1-933565-01-2 steve Bell and Nancy Bratton eBook ISBN:978-1-933565-26-2 title Page: tile masks, ca. 2002. Made by Nora Naranjo-Morse (santa clara, Photography © 2005 National Museum “Published in conjunction with the b. 1953). santa clara Pueblo, New of the american indian, smithsonian exhibition Born of Clay: Ceramics from Mexico. Modeled and painted ceram institution. the National Museum of the American - text © 2005 NMai, smithsonian Indian, on view at the National ic, largest: 7.75 by 4 in. 26/5270. institution. all rights reserved under Museum of the american indian’s Photo by Walter larrimore. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Nazca Culture Azca Flourished in the Ica and Rio Grande De Nazca River Valleys of Southern Peru, Nin an Extremely Arid Coastal Zone Just West of the Andes

Nazca Culture azca flourished in the Ica and Rio Grande de Nazca river valleys of southern Peru, Nin an extremely arid coastal zone just west of the Andes. Nazca chronology is generally broken into four main periods: 1) Proto-Nazca or Nazca 1, from the decline of Paracas culture in the second century BCE until about 0 CE; 2) Early Nazca (or Nazca 2–4), from ca. 0 CE to 450 CE; 3) A transitional Nazca 5 from 450–550 CE; and 4) Late Nazca (phases 6–7), from about 550–750 CE. Nazca 5 witnesses the beginning of environmental changes thought to be associated with the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), cycles of warm and cold water that interrupt the cold, low-salinity Humboldt Current that flows along the Peruvian coast. A 2009 study in Latin American Antiquity suggests that the Nazca may have contributed to this environmental collapse by clearing the land of huarango trees (Prosopis pallida, a kind of mesquite) which played a crucial role in preventing erosion. While best known for their pottery and the Nazca lines (geoglyphs created in the surrounding desert), perhaps their greatest achievement was the construction of extensive puquios, or underground aqueducts channeling water from aquifers, similar in purpose and construction to the qanats of the ancient Middle East. Through the use of puquios the ancient Nazca made parts of the desert bloom; many Nazca puquios remain in use today. Some scholars long doubted that the puquios were made by the Nazca, but in 1995 chronometric dates using accelerator mass spectrometry confirmed dates in the sixth century CE and earlier. -

Mancala: a History

Mancala: A History The name “Mancala” is given to a family of strategy games that are played across the African continent, and which have spread across the globe. It may originally have come from ancient Sumeria. The word “mancala” comes from the Arabic word, “naqala”, which means “to move”. Mancala is essentially a game in which players "sow" and "capture" seeds. This process wasn't always played for fun; in fact, according to some historians, Mancala may have been an ancient record-keeping technique. According to another theory, Mancala originated as a ritual related to the harvest, or may even have been a tool for divination. In some interpretations, the game board represents the world and is best laid in alignment with the rising and setting sun, east to west. The seeds or stones are the stars and the holes are the months of the year. Moving the seeds represents the gods moving through time and space and Mancala predicts our fate. According to some historians, Mancala may have originated with the dawn of civilization. There is limited evidence that the game was played 5,000 years ago in ancient Sumeria (modern day Iraq). The first evidence of the game is a Mancala board from the 4th century AD found in Abu Sha'ar, a late Roman legionary fortress on the Red Sea coast and upper Nile River in Egypt. There is further evidence that Mancala games were played in ancient Egypt before 1400 BCE. Evidence for this theory is available in the form of holes in the ground discovered in Egyptian temples at Tebas, Karnak, and Luxor. -

Experience the Life of South America and Caribbean Islands

Experience the life of South America and Caribbean Islands Beautiful weather rich cultures wonderful people spectacular sites to visit Tour presented by Cristina Garcia, Julie Hale, Laura Hamilton, Lupita Zeferino, Ramona Villavicencio You deserve a vacation of a lifetime Focus South America and the Caribbean will leave you enchanted by the fabulous landscapes, rich cultures and beautiful people. A native and expert guide your tour to each region providing you and your group with the experience of a lifetime. Points of Focus Itinerary Day Port Arrive Depart 1. Ft. Lauderdale --------- 5:00pm 2. At Sea --------- ---------- 3. Puerto Rico 1:30 12:00 midnight 4. Martinique 7:00am 7:00pm 5. Trinidad 8:00am 6:00pm 6. At Sea --------- ---------- 7. At Sea --------- ---------- 8. Cruising Amazon 9:00am 9:00pm 9. Santarem, Brazil 7:00am 10:00pm 10. Cruising Amazon 9:00am 9:00pm 11. Mauaus, Brazil 7:00pm 7:00pm 12.-14. Cruising Amazon 9:00am 4:00pm 15. Iquitos Peru 8:00am 2:00pm 16. Back to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida 9:00am ----------- Inquitos, Peru to Ft. Lauderdale Departure Arrival Airline Flight Travel Time Inquitos, Peru Ft. Lauderale Aero 2118 2 stops next day arrival change planes Delta Air Lines 274/1127 in Lima, Peru and Atlanta Total travel time: 15 h4s. 19 min. Price One way total: $1,346.00 Cruise Itinerary Details Ship Name: Paradise Cruise Line Enchantment of Seas Sailing Date: May 2004, June, 2004, July 2004, August 2004, September 2004 and more etc. Staterooms From: Interior Ocean view Balcony Suite $ 314 $ 426 $ 689 $ 694 Cruise Description Aboard the Paradise Cruise Line leaving Ft. -

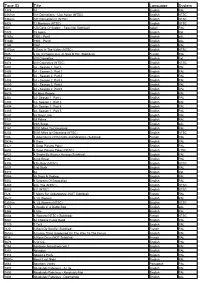

Algeria Ancestors Angola Animals in African Folklore Arabic Folk Literature of North Africa Architecture Archives of Traditional Music Ashanti Astronomy

A Algeria Ancestors Angola Animals in African Folklore Arabic Folk Literature of North Africa Architecture Archives of Traditional Music Ashanti Astronomy back to top B Bamana Banjo: African Roots Bao Bascom, William Basketry, Africa Basketry, African American Beadwork Benin Birth and Death Rituals among the Gikuyu Blacksmiths: Dar Zaghawa of the Sudan Blacksmiths: Mande of Western Africa Body Arts: African American Arts of the Body Body Arts: Body Decoration in Africa Body Arts: Hair Sculpture Botswana Burkina Faso Burundi back to top C Callaway, Bishop Henry Cameroon Cape Verde Cardinal Directions Caribbean Verbal Arts Carnivals and African American Cultures Cartoons Central African Folklore Central African Republic Ceramics Ceramics and Gender Chad Chief Children's folklore: Iteso Songs of War Time Children's folklore: Kunda Songs Children's Folklore: Ndeble Classiques Africaines Color Symbolism: The Akan of Ghana Comoros Concert Parties Congo (Republic of the Congo) Contemporary Bards: Hausa Verbal Artists Cosmology Cote d'Ivoire Cote d'Ivoire, Folklore Crowley, Daniel back to top D Dance: Overview with a Focus on Namibia Decorated Vehicles (Focus on Western Nigeria) Democratic Republic of Congo Dialogic Performances: Call and Response in African Narrating Diaspora: African Communities in the United Kingdom Diaspora: African Communities in the United States Diaspora: African Traditions in Brazil Diaspora: Sea Islands of the USA Dilemma Tales Divination: Household Divination Among the Kongo Divination: Ifá Divination in Cuba Divination: Overview Djibouti Dolls and Toys Drama: Anang Ibibio Traditional Drama Draughts Dreams Dress Drumming: Ewe Dyula back to top E East African Folklore: Overview Education: Folklore in Schools Egypt Electronic Media and Oral Traditions Epics: Liongo Epic of the Swahili Epics: Overview Epics: West African Epics Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Eshu, the Yoruba Trickster Esthetics: Baule Visual Arts Ethiopia Evans-Pritchard, E. -

Mancala Notes

MANCALA Mancala is a name given to a large family of “ Pit and Seeds ” or “ Count, Sow and Capture ” games -- one of the oldest games known! Mancala games have been played the longest and most popular in Africa, though various versions are played all over the world. Boards have been found dating back to 1400 B.C in Eygpt. By 600 A.D. the game had spread to the Middle East and Asia. Surprisingly, the game was little known in Europe until the 19 th Century. In some parts of Africa. Mancala was reserved for royalty and people of rank, and play was limited to the men, or to particular seasons of the year, or to day time. Women had more important chores to do! The name, “Mancala, ” comes from the Arabic word meaning “ to move. ” Names of various games may refer to the board, or the seeds, or manners of play in native languages. Depending on the culture, pieces are “seeds” or “cows.” These two player games are played with a board, usually consisting of two or four equal rows of cup-shaped Pits that may be carved out of wood or stone, or even just dug out of the dirt. The row or rows on each player’s side belong to that player. Sometimes there is also a larger cup-shaped Storehouse for each player on his right side of the board. Several three row games have been found in Northeastern Africa, and modern inventers have even created a one row board with simultaneous play. The playing pieces may be large seeds, pebbles , or marbles , and they belong to a player only when they are in his row of pits. -

Cinema 2: the Time-Image

m The Time-Image Gilles Deleuze Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Caleta M IN University of Minnesota Press HE so Minneapolis fA t \1.1 \ \ I U III , L 1\) 1/ ES I /%~ ~ ' . 1 9 -08- 2000 ) kOTUPHA\'-\t. r'Y'f . ~ Copyrigh t © ~1989 The A't1tl ----resP-- First published as Cinema 2, L1111age-temps Copyright © 1985 by Les Editions de Minuit, Paris. ,5eJ\ Published by the University of Minnesota Press III Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 f'tJ Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 1'::>55 Fifth printing 1997 :])'''::''531 ~ Library of Congress Number 85-28898 ISBN 0-8166-1676-0 (v. 2) \ ~~.6 ISBN 0-8166-1677-9 (pbk.; v. 2) IJ" 2. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or othenvise, ,vithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Preface to the English Edition Xl Translators'Introduction XV Chapter 1 Beyond the movement-image 1 How is neo-realism defined? - Optical and sound situations, in contrast to sensory-motor situations: Rossellini, De Sica - Opsigns and sonsigns; objectivism subjectivism, real-imaginary - The new wave: Godard and Rivette - Tactisigns (Bresson) 2 Ozu, the inventor of pure optical and sound images Everyday banality - Empty spaces and stilllifes - Time as unchanging form 13 3 The intolerable and clairvoyance - From cliches to the image - Beyond movement: not merely opsigns and sonsigns, but chronosigns, lectosigns, noosigns - The example of Antonioni 18 Chapter 2 ~ecaPitulation of images and szgns 1 Cinema, semiology and language - Objects and images 25 2 Pure semiotics: Peirce and the system of images and signs - The movement-image, signaletic material and non-linguistic features of expression (the internal monologue). -

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

Treatment of Head Wounds in Pre-Columbian and Colonial Peru

Treatment of Head Wounds in Pre Columbian and Colonial Peru MARVIN J . ALLISON, PH.D. Professor of Clinical Pathology, Medical College of Virginia, Health Sciences Division of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia ALEJANDRO PEZZIA, PH.D. Curator, Regional Museum oflea, lea, Peru As is frequently the case, art objects often depict visible evidence of additional long-healed fractures the life in a particular civilization, thus giving a visual untreated surgically. Six skulls without fractures had record of a people where the people themselves have evidence of some type of bone disease unrelated to disappeared. Peru is one of the areas of the world trauma. where art depicts the life of the people while the Twenty-four skulls had been trephined or people themselves are present in the form of mum treated surgically by cutting or scraping. Thirteen of mies to confirm much of what is seen in art. A num these skulls showed clear evidence that the surgery ber of ceramic vessels have been found depicting one was due to fracture and one that it was due to disease. man working on the skull of another with a knife. Ten skuHs had evidence of surgery with no clear That such actions were possibly surgical was docu evidence remaining for the cause of the surgery. mented in 1865 when Squier was given a skull with a Table I gives the cultural distribution of the trephined opening made during life. Continued docu material, the pathology when evident, and the surgi mentation of such operations has been reported in cal treatment. The Paracas culture had six out of the literature, but the best studies are in Spanish.1 -s eight individuals with an obvious reason for the skull This paper is a study of the material existing in the surgery. -

NA Boyer Ch 01.V2

CHAPTER 1 Native Peoples of America, to 1500 iawatha was in the depths of despair. For years his people, a group of five HNative American nations known as the Iroquois, had engaged in a seem- ingly endless cycle of violence and revenge. Iroquois families, villages, and nations fought one another, and neighboring Indians attacked relentlessly. When Hiawatha tried to restore peace within his own Onondaga nation, an evil sorcerer caused the deaths of his seven beloved daughters. Grief- stricken, Hiawatha wandered alone into the forest. After several days, he experienced a series of visions. First he saw a flock of wild ducks fly up from the lake, taking the water with them. Hiawatha walked onto the dry lakebed, gathering the beautiful purple-and-white shells that lay there. He saw the shells, called wampum, as symbolic “words” of condolence that, when prop- erly strung into belts and ceremonially presented, would soothe anyone’s grief, no matter how deep. Then he met a holy man named Deganawidah (the Peacemaker), who presented him with several wampum belts and spoke the appropriate words—one to dry his weeping eyes, another to open his ears to words of peace and reason, and a third to clear his throat so that he himself could once again speak peacefully and reasonably. Deganawidah CHAPTER OUTLINE and Hiawatha took the wampum to the five Iroquois nations. To each they introduced the ritual of condolence as a new message of peace. The Iroquois The First Americans, c. 13,000–2500 B.C. subsequently submerged their differences and created a council of chiefs Cultural Diversity, ca. -

A Presentation of the Mancala Games

MANCALA Is actually a large family of “Pit and Seeds ” or “Count, Sow and Capture ” games Description The Mancala games are some of the oldest games known! Boards have been found carved into stone dating back to 1400 B.C in Egypt. •By 600 A.D. the game had spread to the Middle East and Asia. •Surprisingly, the game was little known in Europe until the 19 th Century. •Mancala games have been played the longest in Africa where they are the most popular, though various versions are played all over the world. •The name “Mancala” actually comes from the Arabic word meaning “To Move” •Mancala games have hundreds of names and many versions. Where in the World do they Play Mancala? 300 Names ??? Adi Andada Aweet Ayoayo Ba-awa Bao Kiarabu Baré Bulto Bao la Kiswahili Cela Chisolo Coro Cuba Dabuda Deka Elee Embeli En Dodoi Fifanga Gamacha Hus Igisoro Isafuba Isolo J'odu Kabwenga Kale Kanona Kâra Katra Kiela Ki- Nyamwezi Kiothi Kisolo Kisoro Kisumbi Kpo Krur Lamlameta Layli Leka Li'b Lubasi Lusolo Mangala Mangura Mbangbi Mbele Mbothe Mefuvha Msuwa Mulabalaba Mwambulula Nakabili Ncaya Nchuwa Ndebukya Ngikilees Njombwa Nsumbi Num-Num Oce Omweso Otu Oware Pereauni Qelat Ruhesho Sadéqa Shayo Soro Spreta Tapata Tchadji Tchouba Tihbat Tok Kurou Tokoro Uera Um el Bagara Um el Banat Usolo Wouri Yit ............And that is just some of Them !!! Customs In some parts of Africa, Mancala was reserved for royalty and people of rank, and play was limited to the men, or to particular seasons of the year, or to day time.