Nature and the Environment in Early Buddhism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

References Please Help Making This Preliminary List As Complete As Possible!

Cypraeidae - important references Please help making this preliminary list as complete as possible! ABBOTT, R.T. (1965) Cypraea arenosa Gray, 1825. Hawaiian Shell News 14(2):8 ABREA, N.S. (1980) Strange goings on among the Cypraea ziczac. Hawaiian Shell News 28 (5):4 ADEGOKE, O.S. (1973) Paleocene mollusks from Ewekoro, southern Nigeria. Malacologia 14:19-27, figs. 1-2, pls. 1-2. ADEGOKE, O.S. (1977) Stratigraphy and paleontology of the Ewekoro Formation (Paleocene) of southeastern Nigeria. Bulletins of American Paleontology 71(295):1-379, figs. 1-6, pls. 1-50. AIKEN, R. P. (2016) Description of two undescribed subspecies and one fossil species of the Genus Cypraeovula Gray, 1824 from South Africa. Beautifulcowries Magazine 8: 14-22 AIKEN, R., JOOSTE, P. & ELS, M. (2010) Cypraeovula capensis - A specie of Diversity and Beauty. Strandloper 287 p. 16 ff AIKEN, R., JOOSTE, P. & ELS, M. (2014) Cypraeovula capensis. A species of diversity and beauty. Beautifulcowries Magazine 5: 38–44 ALLAN, J. (1956) Cowry Shells of World Seas. Georgian House, Melbourne, Australia, 170 p., pls. 1-15. AMANO, K. (1992) Cypraea ohiroi and its associated molluscan species from the Miocene Kadonosawa Formation, northeast Japan. Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum 19:405-411, figs. 1-2, pl. 57. ANCEY, C.F. (1901) Cypraea citrina Gray. The Nautilus 15(7):83. ANONOMOUS. (1971) Malacological news. La Conchiglia 13(146-147):19-20, 5 unnumbered figs. ANONYMOUS. (1925) Index and errata. The Zoological Journal. 1: [593]-[603] January. ANONYMOUS. (1889) Cypraea venusta Sowb. The Nautilus 3(5):60. ANONYMOUS. (1893) Remarks on a new species of Cypraea. -

Alstonia Scholaris R. Br

ALSTONIA SCHOLARIS R. BR. Alstonia scholaris R. Br. Apocyanaceae Ayurvedic name Saptaparna Unani name Kashim Hindi names Saptaparna, Chhatwan Trade name Saptaparni Parts used Stem bark, leaves, latex, and flowers Alstonia scholaris – sapling Therapeutic uses lstonia is a bitter tonic, febrifuge, diuretic, anthelmintic, stimulant, carminative, stomachic, aphrodisiac, galactagogue, and haemo- Astatic. It is used as a substitute for cinchona and quinine for the treatment of intermittent periodic fever. An infusion of bark is given in fever, dyspepsia, skin diseases, liver complaints, chronic diarrhoea, and dysentery. Morphological characteristics Saptaparna is a medium-sized evergreen tree, usually 12–18 m high, sometimes up to 27 m high, with close-set canopy. Bark is rough, greyish- white, yellowish inside, and exudes bitter latex when injured. Leaves are four to seven in a whorl, and are thick, oblong, with a blunt tip. They are dark green on the top, and pale and covered with brownish pubescence on the dorsal surface. 21 AGRO-TECHNIQUES OF SELECTED MEDICINAL PLANTS Floral characteristics Flowers are fragrant, greenish-white or greyish-yellow in umbrella-shaped cymes. Follicles (fruits) are narrowly cylindrical, 30 cm × 3 cm, fascicled, with seeds possessing brown hair. Flowering and fruiting occur from March to July, extending to August in subtropical climate. Distribution The species is found in the sub-Himalayan tract from Yamuna eastwards, ascending up to 1000 m. It occurs in tropical, subtropical, and moist de- ciduous forests in India, and is widely cultivated as avenue tree throughout India. Climate and soil The species can be grown in a variety of climatic conditions in India, ranging from dry tropical to sub-temperate. -

ONEP V09.Pdf

Compiled by Jarujin Nabhitabhata Tanya Chan-ard Yodchaiy Chuaynkern OEPP BIODIVERSITY SERIES volume nine OFFICE OF ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY AND PLANNING MINISTRY OF SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT 60/1 SOI PIBULWATTANA VII, RAMA VI RD., BANGKOK 10400 THAILAND TEL. (662) 2797180, 2714232, 2797186-9 FAX. (662) 2713226 Office of Environmental Policy and Planning 2000 NOT FOR SALE NOT FOR SALE NOT FOR SALE Compiled by Jarujin Nabhitabhata Tanya Chan-ard Yodchaiy Chuaynkern Office of Environmental Policy and Planning 2000 First published : September 2000 by Office of Environmental Policy and Planning (OEPP), Thailand. ISBN : 974–87704–3–5 This publication is financially supported by OEPP and may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non–profit purposes without special permission from OEPP, providing that acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purposes. Citation : Nabhitabhata J., Chan ard T., Chuaynkern Y. 2000. Checklist of Amphibians and Reptiles in Thailand. Office of Environmental Policy and Planning, Bangkok, Thailand. Authors : Jarujin Nabhitabhata Tanya Chan–ard Yodchaiy Chuaynkern National Science Museum Available from : Biological Resources Section Natural Resources and Environmental Management Division Office of Environmental Policy and Planning Ministry of Science Technology and Environment 60/1 Rama VI Rd. Bangkok 10400 THAILAND Tel. (662) 271–3251, 279–7180, 271–4232–8 279–7186–9 ext 226, 227 Facsimile (662) 279–8088, 271–3251 Designed & Printed :Integrated Promotion Technology Co., Ltd. Tel. (662) 585–2076, 586–0837, 913–7761–2 Facsimile (662) 913–7763 2 1. -

Indigenous Uses of Ethnomedicinal Plants Among Forest-Dependent Communities of Northern Bengal, India Antony Joseph Raj4* , Saroj Biswakarma1, Nazir A

Raj et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2018) 14:8 DOI 10.1186/s13002-018-0208-9 RESEARCH Open Access Indigenous uses of ethnomedicinal plants among forest-dependent communities of Northern Bengal, India Antony Joseph Raj4* , Saroj Biswakarma1, Nazir A. Pala1, Gopal Shukla1, Vineeta1, Munesh Kumar2, Sumit Chakravarty1 and Rainer W. Bussmann3 Abstract Background: Traditional knowledge on ethnomedicinal plant is slowly eroding. The exploration, identification and documentation on utilization of ethnobotanic resources are essential for restoration and preservation of ethnomedicinal knowledge about the plants and conservation of these species for greater interest of human society. Methods: The study was conducted at fringe areas of Chilapatta Reserve Forest in the foothills of the eastern sub-Himalayan mountain belts of West Bengal, India, from December 2014 to May 2016. Purposive sampling method was used for selection of area. From this area which is inhabited by aboriginal community of Indo-Mongoloid origin, 400 respondents including traditional medicinal practitioners were selected randomly for personal interview schedule through open-ended questionnaire. The questionnaire covered aspects like plant species used as ethnomedicines, plant parts used, procedure for dosage and therapy. Results: A total number of 140 ethnomedicinal species was documented, in which the tree species (55) dominated the lists followed by herbs (39) and shrubs (30). Among these total planted species used for ethnomedicinal purposes, 52 species were planted, 62 species growing wild or collected from the forest for use and 26 species were both wild and planted. The present study documented 61 more planted species as compared to 17 planted species documented in an ethnomedicinal study a decade ago. -

Endangered Species (Protection, Conser Va Tion and Regulation of Trade)

ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSER VA TION AND REGULATION OF TRADE) THE ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND REGULATION OF TRADE) ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Preliminary Short title. Interpretation. Objects of Act. Saving of other laws. Exemptions, etc., relating to trade. Amendment of Schedules. Approved management programmes. Approval of scientific institution. Inter-scientific institution transfer. Breeding in captivity. Artificial propagation. Export of personal or household effects. PART I. Administration Designahem of Mana~mentand establishment of Scientific Authority. Policy directions. Functions of Management Authority. Functions of Scientific Authority. Scientific reports. PART II. Restriction on wade in endangered species 18. Restriction on trade in endangered species. 2 ENDANGERED SPECIES (PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND REGULA TION OF TRADE) Regulation of trade in species spec fled in the First, Second, Third and Fourth Schedules Application to trade in endangered specimen of species specified in First, Second, Third and Fourth Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Importation of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Introduction from the sea certificate for specimens of species specified in First Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Import of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Introduction from the sea of specimens of species specified in Second Schedule. Export of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Import of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Re-export of specimens of species specified in Third Schedule. Export of specimens specified in Fourth Schedule. PART 111. -

Une Ovulidae Singulière Du Bartonien (Éocène Moyen) De Catalogne (Espagne)

Olianatrivia riberai n. gen., n. sp. (Mollusca, Caenogastropoda), une Ovulidae singulière du Bartonien (Éocène moyen) de Catalogne (Espagne) Luc DOLIN 1, rue des Sablons, Mesvres F-37150 Civray-de-Touraine (France) Josep BIOSCA-MUNTS Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya Museu de Geologia « Valenti Masachs » Av. Bases de Manresa, 61-73 E-08242 Manresa (Espagne) David PARCERISA Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya Dpt. d’Enginyeria Minera i Recursos Naturals Av. Bases de Manresa, 61-73 E-08242 Manresa (Espagne) Dolin L., Biosca-Munts J. & Parcerisa D. 2013. — Olianatrivia riberai n. gen., n. sp. (Mollusca, Caenogastropoda), une Ovulidae singulière du Bartonien (Éocène moyen) de Catalogne (Es- pagne). Geodiversitas 35 (4): 931-939. http://dx.doi.org/10.5252/g2013n4aX RÉSUMÉ Les coquilles d’une espèce d’Ovulidae aux caractères totalement inhabituels MOTS CLÉS ont été récoltés dans la partie axiale de l’anticlinal d’Oliana, en Catalogne : Mollusca, Gastropoda, Olianatrivia riberai n. gen., n. sp. (Mollusca, Caenogastropoda), dont la forme Cypraeoidea, et l’ornementation rappellent certaines Triviinae. En accord avec les datations Ovulidae, Pediculariinae, chrono-stratigraphiques connues établies dans le bassin, l’âge de la faune mala- Bartonien, cologique, déplacée à partir d’un faciès récifal, est datée du Bartonien supérieur Bassin sud-Pyrénéen, (Éocène moyen). Il est proposé de placer O. riberai n. gen., n. sp. au sein des Espagne, genre nouveau, Pediculariinae, une sous-famille des Ovulidae (Cypraeoidea), à proximité de espèce nouvelle. Cypropterina ceciliae (De Gregorio, 1880) du Lutétien inférieur du Véronais. GEODIVERSITAS • 2013 • 35 (4) © Publications Scientifiques du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris. www.geodiversitas.com 931 Dolin L. -

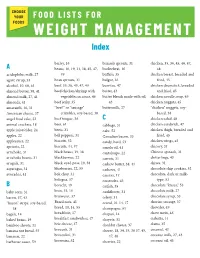

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT Index

CHOOSE YOUR FOOD LISTS FOR FOODS WEIGHT MANAGEMENT Index barley, 16 brussels sprouts, 31 chicken, 35, 36, 45, 46, 47, A beans, 10, 19, 31, 38, 45, 47, buckwheat, 16 48 acidophilus milk, 27 49 buffalo, 35 chicken breast, breaded and agave syrup, 53 bean sprouts, 31 bulgur, 16 fried, 45 alcohol, 10, 60, 61 beef, 35, 36, 45, 47, 49 burritos, 47 chicken drumstick, breaded almond butter, 38, 41 beef/chicken/shrimp with butter, 43 and fried, 45 almond milk, 27, 41 vegetables in sauce, 46 butter blends made with oil, chicken noodle soup, 49 almonds, 41 beef jerky, 35 43 chicken nuggets, 45 amaranth, 16, 31 “beef” or “sausage” buttermilk, 27 “chicken” nuggets, soy- American cheese, 37 crumbles, soy-based, 38 based, 38 angel food cake, 52 beef tongue, 36 C chicken salad, 48 animal crackers, 18 beer, 61 cabbage, 31 chicken sandwich, 47 apple juice/cider, 24 beets, 31 cake, 52 chicken thigh, breaded and apples, 22 bell peppers, 31 Canadian bacon, 35 fried, 45 applesauce, 22 biscotti, 52 candy, hard, 53 chicken wings, 45 apricots, 22 biscuits, 14, 47 canola oil, 41 chicory, 31 artichoke, 31 black beans, 19, 38 cantaloupe, 22 Chinese spinach, 31 artichoke hearts, 31 blackberries, 22 carrots, 31 chitterlings, 43 arugula, 31 black-eyed peas, 19, 38 cashew butter, 38, 41 chives, 31 asparagus, 31 blueberries, 22, 55 cashews, 41 chocolate chip cookies, 52 avocados, 41 bok choy, 31 cassava, 17 chocolate, dark or milk- bologna, 37 casseroles, 45 type, 53 B borscht, 49 catfish, 35 chocolate “kisses,” 53 baby corn, 31 bran, 15, 16 cauliflower, 31 chocolate -

Monastic Investment Bootstrapping: an Economic Model for the Expansion of Early Buddhism

Monastic Investment Bootstrapping: An Economic Model for the Expansion of Early Buddhism MATTHEW D. MILLIGAN Trinity University [email protected] Keywords: monasticism, bootstrapping, patronage, venture capitalism, wealth, Sanchi DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15239/hijbs.02.02.04 Abstract: This paper borrows from recent trends in business finance (namely venture capitalism) to begin theorizing a model for the spread of Buddhism outside of the Buddha’s homeland in ancient Magadha. During the Early Historic Period (300 BCE–300 CE) in South Asia, dozens of new Buddhist pilgrimage sites emerged cen- tered on stūpas, the relics of the Buddha and prominent Buddhist saints. At many of these sites, donor records were etched into stone, thus creating a roster of some of the earliest financiers to the bur- geoning Buddhist monastic institution. I sifted through these donor records to examine just who these early patrons were, where they came from, and potentially what their aims were in funding a new religious movement. Not only did the donative investment records exist for posterity, meaning for the sake of future investors to the Buddhist saṃgha, but they also served as markers of ongoing finan- cial success. If the old adage holds true, that it takes money to make money, then whose money did the early saṃgha utilize to create its image of success for future investors? My research reveals that a ma- jority of the investors to the saṃgha were the monastics themselves. 106 Hualin International Journal of Buddhist Studies, 2.2 (2019): 106–131 AN ECONOMIC MODEL FOR THE EXPANSION OF EARLY BUDDHISM 107 Put simply, monks and nuns formed the largest and most authori- tative patronage demographic from which they used their own personal wealth to, in essence, ‘pull the saṃgha up by its bootstraps’. -

Download Article (PDF)

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO 12S I f I I RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 125 A POCKET BOOK OF THE AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF THE CHILKA LAGOON, ORISSA By T. S. N. MURTHY Southern Regional Station, Zoological Survey of India, Madrar ~VIU Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Calcutta 1990 @ CDpy"g"t, Government IJ!r"dla, 199fJ Published: March, 1990 Price : Inland: Rs. Foreign: £ s Production: Publication Unit. Zoological Survey of India, Calcutta Printed in India by A. Kt. Chatterjee at . Jnanoday. Press. SSS, Kabi Su1Canta Sarani. Calcutta 700 ,O~ and Published by th" 1)jrJOiot. Zoological Surfty of India. Calcutta RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Occasional Paper No. 125 1990 Pages 1-35 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 HIsTORY OF HERPETOLOGY OF THE CHllKA 1 Part I AMPHlTBANS 2 Part II REPTILEs S How TO. FIND AND OBSERVE AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE CHlLKA LAGOON ... 24 CHECKLIST ... 2S GLOSSARY tt. 29 SELCECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY ••• 31 INDEX ••• 33 ACKNOWU:DG~ ,t. 34 Dedicated to the memory of Nelson Annandale who pioneered the faunistic investigations of the Chilka Lake PREFACE The interesting frogs and reptiles of the Chilka lagoon in the State of Orissa seem not to have been given the attention they deserve. This small booklet introduces the few amphibians and many reptiles found in the Chilka Lake, on its several islands and hills, and along the shoreline. Literally, thousands of tourists visit the Chilka Lake round the year. Groups of school boys and girls come here regularly. It is necessary to tell them about the fauna of the lagoon and the ways of its wild denizens. -

Various Terminologies Associated with Areca Nut and Tobacco Chewing: a Review

Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Vol. 19 Issue 1 Jan ‑ Apr 2015 69 REVIEW ARTICLE Various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco chewing: A review Kalpana A Patidar, Rajkumar Parwani, Sangeeta P Wanjari, Atul P Patidar Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Modern Dental College and Research Center, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India Address for correspondence: ABSTRACT Dr. Kalpana A Patidar, Globally, arecanut and tobacco are among the most common addictions. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Tobacco and arecanut alone or in combination are practiced in different regions Modern Dental College and Research Centre, in various forms. Subsequently, oral mucosal lesions also show marked Airport Road, Gandhi Nagar, Indore ‑ 452 001, Madhya Pradesh, India. variations in their clinical as well as histopathological appearance. However, it E‑mail: [email protected] has been found that there is no uniformity and awareness while reporting these habits. Various terminologies used by investigators like ‘betel chewing’,‘betel Received: 26‑02‑2014 quid chewing’,‘betel nut chewing’,‘betel nut habit’,‘tobacco chewing’and ‘paan Accepted: 28‑03‑2015 chewing’ clearly indicate that there is lack of knowledge and lots of confusion about the exact terminology and content of the habit. If the health promotion initiatives are to be considered, a thorough knowledge of composition and way of practicing the habit is essential. In this article we reviewed composition and various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco habits in an effort to clearly delineate various habits. Key words: Areca nut, habit, paan, quid, tobacco INTRODUCTION Tobacco plant, probably cultivated by man about 1,000 years back have now crept into each and every part of world. -

Polynesian Canoe Plants, Including Breadfruit, Taro, and Coconut: the Ultimate in Sustainability Planning Posted on June 27, 2019 by Leslie Lang

HOME HOURS & DIRECTIONS GARDEN SLIDESHOW GARDEN NEWS & BLOG Polynesian Canoe Plants, Including Breadfruit, Taro, and Coconut: the Ultimate in Sustainability Planning Posted on June 27, 2019 by Leslie Lang Do you know about “canoe plants?” These are the plants—such as kalo (taro), ‘ulu (breadfruit), and niu (coconut), among others—that Polynesians brought in their carefully-stocked voyaging canoes perhaps 1,600 years ago when they first settled in Hawai‘i. Canoe plants are one more piece of the evidence showing us that the people who colonized Hawai‘i were intelligent voyagers who came in planned expeditions, not islanders who drifted here unintentionally. Not only did they successfully navigate the oceans like highways, but before they left home to explore and settle new lands, they prepared themselves well. After all, they had to sustain themselves both during their long journeys and also upon arrival in a new island group, where they didn’t know what resources they would find. They maximized their limited space by packing seeds, roots, shoots, and cuttings of their most critical plants, the ones they relied on the most for food, medicine, and for making containers, fabric, cordage, and more. We can identify about 24 plants that arrived in Hawai‘i as canoe plants. You can see samples of some of them at Hawaii Tropical Botanical Garden. The Most Significant Polynesian Canoe Plants: ‘Ulu ‘Ulu (Artocarpus altilis, Artocarpus incisus or Artocarpus communis) belongs to the Moracceae (fig or mulberry) family. Known in English as breadfruit, the ‘ulu tree produces a “fruit” that is actually a vegetable with a high carbohydrate content.