Treaty Education Resources Grade3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Frequency Analyses for New Brunswick Rivers Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2920

Flood Frequency Analyses for New Brunswick Rivers Aucoin, F., D. Caissie, N. El-Jabi and N. Turkkan Department of Fisheries and Oceans Gulf Region Oceans and Science Branch Diadromous Fish Section P.O. Box 5030, Moncton, NB, E1C 9B6 2011 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2920 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Technical reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which is not normally appropriate for primary literature. Technical reports are directed primarily toward a worldwide audience and have an international distribution. No restriction is placed on subject matter and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Technical reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in the data base Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts. Technical reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Numbers 1-456 in this series were issued as Technical Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 457-714 were issued as Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service, Research and Development Directorate Technical Reports. Numbers 715-924 were issued as Department of Fisheries and Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Technical Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 925. Rapport technique canadien des sciences halieutiques et aquatiques Les rapports techniques contiennent des renseignements scientifiques et techniques qui constituent une contribution aux connaissances actuelles, mais qui ne sont pas normalement appropriés pour la publication dans un journal scientifique. -

Striped Bass Morone Saxatilis

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis in Canada Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence Population St. Lawrence Estuary Population Bay of Fundy Population SOUTHERN GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE POPULATION - THREATENED ST. LAWRENCE ESTUARY POPULATION - EXTIRPATED BAY OF FUNDY POPULATION - THREATENED 2004 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2004. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 43 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Jean Robitaille for writing the status report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Claude Renaud the COSEWIC Freshwater Fish Species Specialist Subcommittee Co-chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation de bar rayé (Morone saxatilis) au Canada. Cover illustration: Striped Bass — Drawing from Scott and Crossman, 1973. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/421-2005E-PDF ISBN 0-662-39840-8 HTML: CW69-14/421-2005E-HTML 0-662-39841-6 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – November 2004 Common name Striped Bass (Southern Gulf of St. -

American Eel Anguilla Rostrata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 71 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge V. Tremblay, D.K. Cairns, F. Caron, J.M. Casselman, and N.E. Mandrak for writing the status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair (Freshwater Fishes) COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. Funding for this report was provided by Environment Canada. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’anguille d'Amérique (Anguilla rostrata) au Canada. Cover illustration: American eel — (Lesueur 1817). From Scott and Crossman (1973) by permission. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/458-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43225-8 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name American eel Scientific name Anguilla rostrata Status Special Concern Reason for designation Indicators of the status of the total Canadian component of this species are not available. -

Evaluation of Techniques for Flood Quantile Estimation in Canada

Evaluation of Techniques for Flood Quantile Estimation in Canada by Shabnam Mostofi Zadeh A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Civil Engineering Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2019 ©Shabnam Mostofi Zadeh 2019 Examining Committee Membership The following are the members who served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Veronica Webster Associate Professor Supervisor Donald H. Burn Professor Internal Member William K. Annable Associate Professor Internal Member Liping Fu Professor Internal-External Member Kumaraswamy Ponnambalam Professor ii Author’s Declaration This thesis consists of material all of which I authored or co-authored: see Statement of Contributions included in the thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Statement of Contributions Chapter 2 was produced by Shabnam Mostofi Zadeh in collaboration with Donald Burn. Shabnam Mostofi Zadeh conceived of the presented idea, developed the models, carried out the experiments, and performed the computations under the supervision of Donald Burn. Donald Burn contributed to the interpretation of the results and provided input on the written manuscript. Chapter 3 was completed in collaboration with Martin Durocher, Postdoctoral Fellow of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Waterloo, Donald Burn of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Waterloo, and Fahim Ashkar, of University of Moncton. The original ideas in this work were jointly conceived by the group. -

A Report on Recapture from a 1968 Native Salmon Smolt Tagging

RESTRICTED THE NORTHWEST ATLANTIC FISHERIES INTERNA nONAl COMMISSION FOR ICES/ICNAF Salmon Doc. 71/15 Serial No. 2541 (also ICNAF Res.Doc. 71/71) (B.g.14) ANNUAL MEETING - JUNE 1971 A Report on Recapture from a 1968 Native Salmon Smolt Tagging Project on the Miramichi River by G.E. Turner Resource Development Branch Department of Fisheries and Forestry of Canada Halifax, Nova Scotis l.t INTRODUCTION A program to evaluate the contribution of hatchery reared salmon smolts to sport and commercial fisheries in the Atlantic region was started in 196B. Part of this program included the tagging of wild native smolts in selected.rivers for comparison of returns with hatchery releases. This report presents results on 1969 and 1970 recaptures of wild native smolts tagged and released in the Miramichi River in 196B. The Miramichi River (Figure 1) is located in New Brunswick, has a drainage area of over 5,500 square miles and empties into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. 2.0 METHODS AND MATERIALS The native smolts used for the tagging project were captured in the estuary on their seaward migration and are representativ~ of the whole river and not one particular tributary. Fish were selected for tagging because of their vigor and good physical appearance (lack of scaled areas, abrasions, fun gal growth or'decayed fins). Although size was not a determining factor in selection of smolts for tagging, those under 12 cm. were culled as a precaution against damage from tagging needles. Tags used on all smolts were the modified Carlin type tied with black monofilament nylon twine and applied with a double needle tagging jig. -

In DFO Gulf Region (New Brunswick Salmon Fishing Areas 15 And

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Gulf Region Science Response 2015/008 UPDATE OF STOCK STATUS OF ATLANTIC SALMON (SALMO SALAR) IN DFO GULF REGION (NEW BRUNSWICK SALMON FISHING AREAS 15 AND 16) FOR 2014 Context The last assessment of stock status of Atlantic salmon for Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Gulf Region was completed after the 2013 return year (DFO 2014). DFO Fisheries and Aquaculture Management (FAM) requested an update of the status of the Atlantic Salmon stocks in DFO Gulf Region for 2014. Indicators for adult and juvenile Atlantic Salmon stocks of the Restigouche River (Salmon Fishing Area 15) and the Miramichi River (SFA 16) are provided in this report. Juvenile indices for the Buctouche River (SFA 16) are also provided. This Science Response Report results from the Science Response Process of December 11, 2014 on Indicators for Atlantic Salmon for Gulf New Brunswick rivers (SFA 15, 16). No additional publications from this process are anticipated. Background All rivers flowing into the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence are included in DFO Gulf Region. Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) management areas in DFO Gulf Region are defined by four salmon fishing areas (SFA 15 to 18) encompassing portions of the three Maritime provinces (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island). For management purposes, Atlantic Salmon are categorized as small salmon (grilse; fish with a fork length less than 63 cm) and large salmon (fish with a fork length equal to or greater than 63 cm). Analysis and Response Abundance indices of adult salmon Information on adult salmon abundance is provided for the Restigouche River of SFA 15 and the Miramichi River of SFA 16. -

MREAC, 2010 & Overview of Past Three Years

MREAC, 2010 & Overview of Past Three Years Kara L. Baisley Freshwater Mussel Survey of the Miramichi River Watershed – MREAC, 2010 & Overview of Past Three Years Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................ ii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... iii 1.0. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0. Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 2 3.0. Results and Observations .................................................................................................................. 5 4.0. Discussion & Review ......................................................................................................................... 8 4.1. Eastern Pearlshell ( Margaritifera margaritifera ) ................................................................... 10 4.2. Eastern Elliptio ( Elliptio complanata ) ..................................................................................... 11 4.3. Eastern Floater (Pyganodon -

Brief Presentation to the House of Common's Standing Committee On

Brief Presentation to the House of Common’s Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans on the Impact of the Rapid Increase of the Striped Bass in The Miramichi River and the Gulf of St. Lawrence BY: John Bagnall, Chair, Fisheries Committee, the New Brunswick Salmon Council DATE: March 4, 2019 The New Brunswick Salmon Council (the NBSC) is an Atlantic salmon conservation coalition comprised of 25 fish & game, environmental and First Nations organizations. A large majority of the members of our component organizations are primarily Atlantic salmon sport fishery participants and proponents, and they view wild salmon conservation as a means to achieve better recreational fishing results. Many also fish for other species, and support the establishment and maintenance of “good” fishing for species such as striped bass, brook trout, and smallmouth bass as well as salmon. As an introduction, the following is an explanation of the differences between recreationally fishing for Atlantic salmon and striped bass, and a discussion of what differentiates “good” from “bad” fishing for each. Fishing for “bright” Atlantic salmon (as opposed to post-spawned “black” salmon or kelts) is not for the impatient. Sea-run Atlantic salmon sport fishing in eastern Canada is conducted only by means of fly-fishing, a technique that takes patience for an angler to rise above even the level of ineptitude. “Bright” salmon are on their spawning run, and in fresh water do not feed. Therefore, even when employing proper fly-fishing techniques, it can be extremely difficult for anglers, to hook them. Salmon fishing occurs above the tidal limit in flowing water. -

The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: B2 the Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos" J.H

GAC-MAC-CSPG-CSSS Pre-conference Field Trips A1 Contamination in the South Mountain Batholith and Port Mouton Pluton, southern Nova Scotia HALIFAX Building Bridges—across science, through time, around2005 the world D. Barrie Clarke and Saskia Erdmann A2 Salt tectonics and sedimentation in western Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia Ian Davison and Chris Jauer A3 Glaciation and landscapes of the Halifax region, Nova Scotia Ralph Stea and John Gosse A4 Structural geology and vein arrays of lode gold deposits, Meguma terrane, Nova Scotia Rick Horne A5 Facies heterogeneity in lacustrine basins: the transtensional Moncton Basin (Mississippian) and extensional Fundy Basin (Triassic-Jurassic), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia David Keighley and David E. Brown A6 Geological setting of intrusion-related gold mineralization in southwestern New Brunswick Kathleen Thorne, Malcolm McLeod, Les Fyffe, and David Lentz A7 The Triassic-Jurassic faunal and floral transition in the Fundy Basin, Nova Scotia Paul Olsen, Jessica Whiteside, and Tim Fedak Post-conference Field Trips B1 Accretion of peri-Gondwanan terranes, northern mainland Nova Scotia Field Trip B2 and southern New Brunswick Sandra Barr, Susan Johnson, Brendan Murphy, Georgia Pe-Piper, David Piper, and Chris White The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: B2 The Joggins Cliffs of Nova Scotia: Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos" J.H. Calder, M.R. Gibling, and M.C. Rygel Lyell & Co's "Coal Age Galapagos” B3 Geology and volcanology of the Jurassic North Mountain Basalt, southern Nova Scotia Dan Kontak, Jarda Dostal, -

Angling Report Newsletter

“SERVING THE ANGLER WHO TRAVELS” $5 A MONTHLY NEWSLETTER THE ANGLING REPORT July 2010 Vol. 23, No. 7 n the past 25 years, I’ve been for- “new” Restigouche River Lodge that DATELINE: NEW BRUNSWICK tunate to fish many salmon rivers is now taking paying guests. The Atlantic Salmon I in Russia, Ireland and eastern lodge, which was purchased in late On-Site Report On That Canada, some of them famous, many 2008 by a syndicate of six men from obscure. But try as I might, I’d never New Jersey, New York and New Eng- New Restigouche Lodge been able to wet a line in the land, quietly began taking guests in Restigouche. Without personal or po- 2009 and is now fully open for business. The main contact person is (Editor Note: In the rarified world of high- Harry Huff, who owns Streams of end Atlantic salmon fishing, the Resti- gouche River on the border between New Dreams Fly Shop (www.streamsof Brunswick and Quebec has been one of the dreams.com. Tel. 201-934-1138. Cell: most exclusive of fishing venues. With a few 201-788-3131). Harry, by the way, is notable exceptions, such as Red Pine Camp a larger-than-life character, a former which has recently gone private, unless you tree surgeon and absolutely fanatic were lucky enough to inherit a membership in one of the clubs that control most of the angler. Good company in a salmon river and its tributaries, or you lived long camp. enough to work your way up a long waiting For those who know the Resti- list, you fished the Restigouche by invita- gouche and its fishing establish- tion only. -

Striped Bass,Morone Saxatilis

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence population Bay of Fundy population St. Lawrence River population in Canada Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence population - SPECIAL CONCERN Bay of Fundy population - ENDANGERED St. Lawrence River population – ENDANGERED 2012 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2012. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. iv + 82 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2004. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Striped Bass Morone saxatilis inCanada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 43 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Jean-François Bourque and Valerie Tremblay for writing the status report on the Striped Bass, Morone saxatilis, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Dr. Eric Taylor, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Bar rayé (Morone saxatilis) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Striped Bass — Illustration from Scott and Crossman, 1973. -

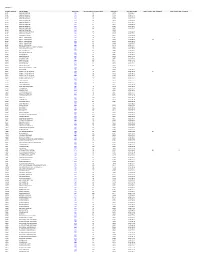

Bridge Condition Index

DISTRICT 2 BRIDGE NUMBER BRIDGE NAME MAP PAGE BRIDGE CONDITION INDEX (BCI) YEAR BUILT LAST INSPECTION POSTED LOAD LIMIT (TONNES) POSTED AXLE LIMIT (TONNES) B102 BARNABY RIVER #1 203 96 1974 2014-08-11 B105 BARNABY RIVER #2 219 98 1976 2014-07-15 B108 BARNABY RIVER #3 219 79 1966 2014-07-15 B111 BARNABY RIVER #4 219 90 1958 2014-07-17 B114 BARNABY RIVER #5 219 79 1954 2014-07-17 B120 BARNABY RIVER #7 234 77 1972 2015-08-19 B123 BARNABY RIVER #8 234 42 1925 2015-08-19 B126 BARNABY RIVER #9 234 75 1981 2015-08-19 B129 BARNABY RIVER #10 234 88 1965 2014-07-17 B133 BARNABY RIVER #12 234 2014 B138 BARTHOLEMEW RIVER #1 232 77 1978 2015-08-20 B141 BARTIBOG RIVER #1 190 75 1976 2015-07-15 B144 BARTIBOG RIVER #2 173 75 1950 2015-08-06 B204 BAY DU VIN RIVER #1 191 74 1982 2015-08-05 B207 BAY DU VIN RIVER #2 191 71 1967 2015-08-05 18 3 B210 BAY DU VIN RIVER #4 221 87 1992 2015-08-05 B213 BAY DU VIN RIVER #5 220 92 1968 2014-07-17 B216 BAY DU VIN RIVER #7 220 28 1971 2014-07-17 B282 BEAVERBROOK BLVD. NBECR OVERPASS 204 96 1981 2014-08-11 B438 BIG ESKEDELLOC RIVER 156 76 1984 2015-08-06 B456 BIG HOLE BROOK 263 90 1996 2015-08-20 B459 BIG MARSH BROOK #1 136 79 1989 2014-08-12 B489 BLACK BROOK 249 53 1971 2014-07-15 B501 BLACK BROOK #1 190 66 1966 2015-07-14 B534 BLACK RIVER #2 190 94 1976 2015-07-14 B543 BLACK RIVER #3 205 100 1977 2014-07-17 B564 BLACK RIVER #5 205 47 1961 2014-07-17 B630 BOGAN BROOK 277 41 1976 2014-07-14 B753 BRUCE BROOK #1 261 98 1993 2014-07-14 B760 BRYENTON-DERBY (RTE.