Page 1 of 107 the Story of Potters Bar and South Mimms. Published In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

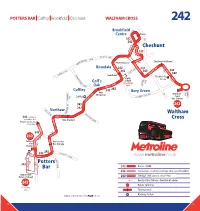

Potters Bar to Cheshunt and Waltham Cross

POTTERS242 BAR Cuffley Brookfield Cheshunt WALTHAM CROSS Potters Bar to Cheshunt 242 and Waltham Cross Brookfield Centre Tesco A 242 1 0 242 D W L E ST H I F E T Cheshunt K W E O O E F R I B N R E 242 A O L L A D D S LONGFIELD LANE D ROA REET NDST CHURCH Cheshunt Old Pond MO Jolly M “The Freemasons” C LANE HA Bricklayers H R U C O R R S C O Rosedale E H . S W D 242 G 242 D S R T S A A A R B L Y L T E E R 242 IL E 242 E 242 G E O E H LE T ICL GOFF’S LANE L O RN CO K 242 DA N E Fourfields W Theobald’s H G S I A T G T Goffs R E Grove E H S N D E T School R A T R G Goff’s O E Y E R T E Schooldays R R AN U OAD S L Only B Oak OFF’ G 242 Cuffley 242 MONARCHS Bury Green WAY War A S 1 L Y 0 D IL WA Waltham R LIS L H Memorial EL A L NT I A Y Cuffley Y LIEUTEN Cross E H N I FFLE Bus Station V U C . D R 242 242 S D 242 R W A E Y Northaw E LL N R I O V C Waltham A A D TT JUDGE’S LE 242 continues GA C T HILL E Cross to Hatfield and O R Two Brewers OA O D Welwyn Garden City P E on Sundays R S A L 1 A 0 . -

HERTS COUI~TY COUNCIL. --+-- Local Government Act, 1888, 51 & 52 Vic

[ KELJ~Y'8 8 HERTFORDSHIRE. HERTS COUI~TY COUNCIL. --+-- Local Government Act, 1888, 51 & 52 Vic. c. 41. Under the above Act, He.rts, after the 1St April, 1889, The coroners for the county are elected by the Oounty for the p~oses (}f the Act, became an administrative Council, and the clerk of the peace appointed by such county (sec. 46), governed by a County Oouncil, con- joint committee, and may be removed by tliem (800. sisting of chairman, alderme,n and councillors, ele,cted in 83-2). ~h al I manner prescribed by the Act (sec. 2). The clerk0 f " e peace for the coont·y IS SO C erk 0 f the The chairman, bv. virtue of his office, is a justice . County Cooncil (ilec. 83-1. ) ()f the peace for the county, without qualification (sec. 46). The police for the county are under the control of a The administrative business of the county (which standing joint committee of the Quarter Sessions, and would, if this Act had not been passed, have been trans the County Council, appointed as therein mentioned acted by the justices) is transacted by the County Council. (sec. 9). Meet Quarterly at Hertford & St. Albans alternately at 12 nOOn Mondays. Chairman-Sir John Evans KC.B., D.L., D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S., Nash Mills, Hemel Hempstead. Vice-Chairman-The Right Hon. Thomas Frederick Halsey M.P., Gaddesden Place, Hemel Hempstead. Aldermen. Retire in 1904. Halsey Right Hon. Thomas Frederick P.C., M.P., J.P. Salisbury Marquess of K.G., P.C., D.C.L., F.R.S. -

Herts Valleys CCG PCN Mapping - Community Pharmacy Alignment

Herts Valleys CCG PCN Mapping - Community Pharmacy alignment PCN and page numbers: Dacorum 1 Alliance - P.2 2 Alpha - P.2 3 Beta - P.2 4 Danais - P.3 5 Delta - P.3 Hertsmere 6 HertsmereFive - P.3 7 Potters Bar - P.4 St Albans and Harpenden 8 Abbey Health - P.4 9 Alban Healthcare - P.4 10 Harpenden - P.4 11 HLH - P.5 Watford and Three Rivers 12 Attenborough & Tudor Surgery - P.5 13 Central Watford and Oxhey - P.5 14 Grand Union - P.6 15 Manor View Pathfinder - P.6 16 North Watford - P.6 17 Rickmansworth & Chorleywood - P.7 1 Primary Care Networks (PCNs) and Practices Community Pharmacies aligned to the PCN (listed in alphabetical order) PCN Alliance Alliance Coleridge House Medical Centre Grovehill Pharmacy (FFE61) Practices involved in Colney Medical Centre (Verulam Medical Group) Lloyds Pharmacy Sainsburys London Colney (FDX05) PCN Grovehill Medical Centre Well Pharmacy London Colney (FP498) Theobald Medical Centre Woodhall Pharmacy (FLP62) Woodhall Farm Medical Centre CP Lead: tbc PCN Alpha Alpha Berkhamsted Group Practice Acorn Chemist (FFQ63) Practices involved in Gossoms End Surgery Boots Pharmacy Berkhamsted (FPJ31) PCN Manor Street HH Dickman Chemist (FGQ23) Rothschild House Group Hubert Figg Pharmacy (FLG84) Lloyds Pharmacy Chapel Street Tring (FGP13) Lloyds Pharmacy High Street Tring (FLH81) Markyate Pharmacy (FKG66) Rooneys Pharmacy (FQ171) CP Lead: Mitesh Assani, Acorn Pharmacy Berkhamsted PCN Beta (40,186) Beta (40,186) Fernville Surgery Boots Pharmacy Marlowes Hemel Hempstead (FG698) Practices involved in Highfield Surgery -

Hertfordshire. [ Kelly's

4 HERTFORDSHIRE. [ KELLY'S The New River is an artificial cut, made to convey D'f St. Albans, in the diocese of St. Albans and province water to London; it was begun in r6o8, and runs along of Canterbury, and is divided into the following rural the valley of the Lee, taking its chief supplies from deaneries :-Baldock, Barnet, Bennington, Berkhamsted, Amwell and Chadwell, two springs near Hertford. Bishop Stortford, Buntingford, Hertford, Hitchin, St. The Grand Junction Canal comes into Hertfordshire Albans, Ware, Watford,. and Welwyn. near Tring, and soon enters the valley of the Gade, and St. Albans, which has been erected into a Cathedral City, had a. population in 1891 of 12,898. Hertford is a afterwards that of the Colne, which it follows through • Middlesex to West Drayton, passing by Tring, Berkham municipal borough, population 7•548. The other towus sted, Hemel Hempstead, Watford and Rickmansworth, are Baldock, population 2,301; Barnet, 5,496; Berkham with branches to .Aylesbury and Wendover. sted, 2,135; Bishop Stortford~ 6,595; Cheshunt, g,63o; Hatfield, 4,693; Hemel Hempstead, 4,336; Hitchin, 8,86o; Four main lines, belonging to as many large com Hoddesdon, 3,650; Rickmansworth, 3,730; Royston, panies, pass t'hrough the county from south to north, 3,319; Sawbridgeworth, 2,150; Stevenage, 3,309; Tring, viz., the London and North-Western on the western 4,525; Ware, 5,706; Watford, 16,826; Welwyn, 1,745. border, the Midland through the mid-west portion, the Great NO'rthern through the Centre, and the Great Eastern The Registration Districts are:- along the ~tern border. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD ENGINEER'S OFFICE Engineers' reports and letter books LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD: ENGINEER'S REPORTS ACC/2423/001 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1881 Jan-1883 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/002 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1884 Jan-1886 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/003 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1887 Jan-1889 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/004 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1890 Jan-1893 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/005 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1894 Jan-1896 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/006 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1897 Jan-1899 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/007 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1903 Jan-1903 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/008 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1904 Jan-1904 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/009 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1905 Jan-1905 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/010 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1906 Jan-1906 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates ACC/2423/011 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1908 Jan-1908 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/012 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1912 Jan-1912 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/013 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1913 Jan-1913 Lea navigation/ stort navigation -

Response to Hertfordshire County Council South

Walking in Hertfordshire – Time to Reverse 60+ Years of Loss of Walking Routes South Herts Living Streets Manifesto for Walking in South Hertfordshire South Herts Living Streets Group is dedicated to improving walking routes in South Hertfordshire, including part of the London Borough of Barnet that was previously in Hertfordshire. We focus on walking routes between North London and Hertfordshire, from Apex Corner at Mill Hill and High Barnet Station North towards Borehamwood, South Mimms, North Mymms, Welham Green, Hatfield, Stanborough and Welwyn Garden City. We also propose an East-West walking route from the Herts/Essex border at Waltham Abbey to Waltham Cross, Cuffley, Northaw, Potters Bar, South Mimms, Ridge and Borehamwood. Our comprehensive survey of walking in South Herts shows a major loss of pavements and safe walking routes due to motorways and trunk roads that were built in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. These have had a major impact on walking routes in the South Hertfordshire Area. Many walking routes that go along or across major roads have been lost or have become unsafe due to: A6 South Mimms Bypass (1958) A1 Mill Hill to South Mimms change to dual carriageway (1960s and 1970s) London 'D' Ring Road/M25 (1971) A1(M) Junction 1/M25 Junction 23 at South Mimms (1972) A1(M) Junctions 1 - 2 South Mimms to South Hatfield (1970s) A1(M) Junction 3 and Hatfield Tunnel (1982). Since then more walking routes have been lost because some footways beside roads were planned but were never built and other footways that existed in the past were buried under banks of earth. -

Community and Business Guide

FC_THR_307740.qxd 1/8/11 14:53 Page 3 FC_THR_307740.qxd 1/8/11 14:53 Page 4 ED_THR_307740.qxd 28/7/11 12:53 Page 1 SAVING MONEY FOR SW Hertfordshire’s Thrive Homes and its customers have BUSINESS CLIENTS longest established lots to celebrate. Created in March 2008, Thrive Homes received THROUGHOUT THE THREE theatre school resounding support with four out of RIVERS DISTRICT five tenants voting to transfer across A full programme of classes for from Three Rivers District Council. children (3 - 18 years), Adults and Students in Ballet, Jazz, Contemporary, Character, • 2,000 properties have already benefited I.S.T.D. Tap and Modern Dance, from our £43 million, 5 year Singing and Musical Theatre, Drama improvement programme. (including L.A.M.D.A. examinations), regular performances and much • Resident elections for Board more. Recognised examinations up membership – promised and • RENT REVIEWS delivered: a third of our Board to Major Level and Associate members are tenants and • LEASE RENEWALS Teacher Major examinations and leaseholders. • VALUATIONS teaching qualifications (I.S.T.D., • ACQUISITION OF OFFICE, RETAIL A.R.B.T.A. and L.A.M.D.A.) • Closer working with partner agencies AND FACTORY PREMISES such as the Citizens Advice Bureau to • DISPOSAL OF OFFICE, RETAIL AND better support our tenants and Courses for Students 16+ full or residents. FACTORY PREMISES part-time available. • ADVICE ON DEVELOPMENT • Greater understanding of our tenants • BUILDING CONDITION SURVEYS One year foundation course. and leaseholders so services can be AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT tailored to individual needs. • PLANNING ADVICE • Hundreds adaptations completed so people can live in their own homes HIGH QUALITY COMMERCIAL safely. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

160314 07Ci HIWP 2016&17 and FWP 2017&18 Appendix C

Integrated Works Programme 2016-2017 Cabinet Eastern Herts & Lea Valley Broxbourne Scheme Delivery Plan 97 schemes Commissioning Records SRTS Small Works Pilot Delivery 16/17 BROXBOURNE (District wide) ITP16031 Broxbourne SBroxbourne: Area Road Sections: BR/0 SRTS Small Works Prep 16/17 BROXBOURNE (District wide), COM16009 Broxbourne IBroxbourne: Area; Dacorum: Dacorum Area; East Herts: East DACORUM (District wide), Herts Area; Hertsmere: Hertsmere Area; North Herts: North Herts Area; St EAST HERTS (District wide), Albans: St Albans Area; Stevenage: Stevenage Area; Three Rivers: Three HERTSMERE (District wide), Rivers Area; Watford: Watford Area; Welwyn Hatfield: Welwyn Hatfield NORTH HERTS (District wide), Area ST ALBANS (District wide), Road Sections: BR/0 DA/0 EH/0 HE/0 NH/0 SA/0 ST/0 TR/0 WA/0 STEVENAGE (District wide), WH/0 THREE RIVERS (District wide), WATFORD (District wide), WELWYN HA Maintenance A Road Programme A10 Northbound nr Hailey Surface Dressing Hoddesdon South, Ware South Northbound:ARP15177 Broxbourne WA10 Boundary To North Gt Amwell Roundabout; Hertford A10 Northbound Offslip: Nb Offslip For Great Amwell Interchange; A10 Northbound: North Hoddesdon Link Rbt To East Herts Boundary; A10 Northbound: Northbound Onslip From Hoddesdon Interchange Road Sections: A10/331/334/337/340 A10 South Bound & Northbound Interchange Hoddesdon South, Ware South Northbound:ARP17183 Baas HillSA10 Bridge To North Hoddesdon Link Rbt; A10 Reconstruction Southbound: North Rush Green Rbt To North Gt Amwell Rbt; A10 Great Amwell Roundabout: Roundabout -

St Albans and District Tourism Profile and Strategic Action Plan

St Albans and District Tourism Profile and Strategic Action Plan Prepared by Planning Solutions Consulting Ltd March 2021 www.pslplan.co.uk 1 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Setting the Scene 3. Support infrastructure and marketing 4. Business survey 5. Benchmarking: comparator review 6. Tourism profile: challenges and priorities 7. Strategic priorities and actions Key contact David Howells Planning Solutions Consulting Limited 9 Leigh Road, Havant, Hampshire PO9 2ES 07969 788 835 [email protected] www.pslplan.co.uk 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Background This report sets out a Tourism Profile for St Albans and District and outlines strategic priorities and actions to develop the visitor economy in the city and the wider district. The aim is to deliver a comprehensive Tourism Strategic Action Plan for St Albans to provide a roadmap for the district to move forward as a visitor destination with the engagement and support of key stakeholders. Delivery of the plan will be a collaborative process involving key stakeholders representing the private and public sectors leading to deliverable actions to guide management and investment in St Albans and key performance indicators to help leverage the uniqueness of St Albans to create a credible and distinct visitor offering. Destination management and planning is a process of coordinating the management of all aspects of a destination that contribute to a visitor’s experience, taking account of the needs of the visitors themselves, local residents, businesses and the environment. It is a systematic and holistic approach to making a visitor destination work efficiently and effectively so the benefits of tourism can be maximised and any negative impacts minimised. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 EXHBITION FACT SHEET Title; THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons: Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates; November 3, 1985 through March 16, 1986, exactly one week later than previously announced. (This exhibition will not travel. Loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late summer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits; This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration v\n.th the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. History of the exhibition; The suggestion that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art was made by the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery, responded with the idea of an exhibition on the British Country House as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

Urban Nature Conservation Study

DACORUM BOROUGH COUNCIL URBAN NATURE CONSERVATION STUDY Hertfordshire Biological Records Centre March 2006 DACORUM BOROUGH COUNCIL URBAN NATURE CONSERVATION STUDY Hertfordshire Biological Records Centre March 2006 SUMMARY Purpose of study The environment is one of the four main drivers of sustainable development, and in this context biodiversity needs to be fully integrated into planning policy and delivery. As part of the new planning system known as the Local Development Framework, information on urban wildlife is fundamental given the pressure on land resources in and around our towns. The aims of the study are: ‘To provide a well reasoned and coherent strategy for the protection and enhancement of key wildlife areas and network of spaces / natural corridors within the towns and large villages of Dacorum’. The Dacorum Urban Nature Conservation Study considers the wildlife resources within the six major settlements in Dacorum, namely Berkhamsted, Bovingdon, Hemel Hempstead, Kings Langley, Markyate and Tring. They were mapped using existing habitat information, additional sites identified from aerial photo interpretation and local knowledge. The areas adjacent to each settlement – up to a distance of 1km – were also mapped in a similar fashion to place the urban areas within the context of their surrounding environments. This process identified the most important sites already known such as Sites of Special Scientific Interest, local sites meeting minimum standards known as ‘Wildlife Sites’, and other sites or features of more local significance within the urban areas known collectively as ‘Wildspace’. These incorporated Hertfordshire Biological Record Centre’s ‘Ecology Sites’ where appropriate, old boundary features such as hedgerows and tree lines, as well as significant garden areas or open spaces which may survive.