The Ancestry of the Thoroughbred

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thoroughbred Horses

Thoroughbred Horses Visit Funny Cide at the KHP Hall of Champions! A long time ago, man tamed the horse. People used horses to farm and to ride. Today, people also race horses. The most popular breed for horse racing is the Thoroughbred. The Thoroughbred is the only horse that can compete in the Kentucky Derby. * This educational packet is intended for third, fourth, and fifth graders. It may be complete in small groups or individually. ! Name:_______________________________ Date:________________________________ The Life Cycle of a Thoroughbred Racehorse Racehorses are born on farms. 1 Baby horses are called foals. ! ! Mother horses are called Mares. Foals live with their mothers. Father horses are called Stallions. 2 ! ! When foals are about six months old they are weaned, meaning separated from their mothers. 3 Weanlings live in a herd made of up horses their age. ! ! When horses turn one year old, they are called yearlings. At this point, boy horses are called colts, and girl horses are called fillies. 4 ! ! 5 Horses start racing at two years old. ! ! Racehorses retire on farms after (hopefully) long careers. Some racehorses become pleasure horses, while others are bred to produce more 6 racehorses. ! ! What about horses? Where do horses live? Horses live in barns and outside. In a barn, a horse lives in a stall. Outside, a horse lives in a pasture. ! White Prince A Rare White Thoroughbred Visit him at the KHP! ! ! What do horses eat? Horses eat a lot during the day. From the time they are born, until they are about 5 months old, foals need to drink their mother’s milk. -

Herd/Partnership Number: ______Name: ______

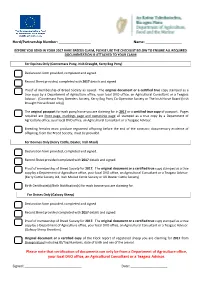

Herd/Partnership Number: ________________ Name: __________________ BEFORE YOU SEND IN YOUR 2017 RARE BREEDS CLAIM, PLEASE USE THE CHECKLIST BELOW TO ENSURE ALL REQUIRED DOCUMENTATION IS ATTACHED TO YOUR CLAIM For Equines Only (Connemara Pony, Irish Draught, Kerry Bog Pony) Declaration form provided, completed and signed. Record Sheet provided, completed with 2017 details and signed. Proof of membership of Breed Society as issued. The original document or a certified true copy stamped as a true copy by a Department of Agriculture office, your local DVO office, an Agricultural Consultant or a Teagasc Advisor. (Connemara Pony Breeders Society, Kerry Bog Pony Co-Operative Society or The Irish Horse Board (Irish Draught Horse Breed only)) The original passport for each pony/horse you are claiming for in 2017 or a certified true copy of passport. Pages required are front page, markings page and ownership page all stamped as a true copy by a Department of Agriculture office, your local DVO office, an Agricultural Consultant or a Teagasc Advisor. Breeding females must produce registered offspring before the end of the contract; documentary evidence of offspring, from the Breed Society, must be provided. For Bovines Only (Kerry Cattle, Dexter, Irish Maol) Declaration form provided, completed and signed. Record Sheet provided completed with 2017 details and signed. Proof of membership of Breed Society for 2017. The original document or a certified true copy stamped as a true copy by a Department of Agriculture office, your local DVO office, an Agricultural Consultant or a Teagasc Advisor. (Kerry Cattle Society Ltd, Irish Moiled Cattle Society or UK Dexter Cattle Society) Birth Certificate(s)/Birth Notification(s) for each bovine you are claiming for. -

Multiple Choice Choose the Answer That Best Completes Each Statement Or Question

Name Date Hour 9 The Horse Industry Multiple Choice Choose the answer that best completes each statement or question. _______ 1. The horse was first domesticated in Europe and Asia about ____ . A. 1,000 years ago B. 3,000 years ago C. 5,000 years ago D. 8,000 years ago _______ 2. Horses were brought to the New World by Spanish explorers in the ____ . A. 15th century B. 16th century C. 17th century D. 18th century _______ 3. Horses are measured in terms of hands with a hand being ____ . A. two inches B. four inches C. six inches D. eight inches _______ 4. Ponies are shorter than horses and can be anywhere from 8 to ____ . A. 10 hands high B. 12.2 hands high C. 14.2 hands high D. 16 hands high _______ 5. Which horse breed is considered the oldest purebred horse in the world? A. Arabian B. Appaloosa C. Thoroughbred D. Quarter Horse Introduction to Agriscience | Unit 9 Test CIMC 1 _______ 6. Which horse breed has as one of its characteristics a distinctive spotted coat? A. Arabian B. Appaloosa C. Thoroughbred D. Quarter Horse _______ 7. Which horse breed was developed in the United States and got its name because of its great speed at short distances? A. Arabian B. Appaloosa C. Thoroughbred D. Quarter Horse _______ 8. Which horse breed was developed in the deserts of the Middle East? A. Arabian B. Appaloosa C. Thoroughbred D. Quarter Horse _______ 9. Which horse breed has a head characterized by a dished profile, prominent eye, large nostrils, and small muzzle? A. -

Horse and Burro Management at Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Horse and Burro Management at Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge Environmental Assessment Before Horse Gather, August 2004 September 2002 After Horse Gather, August 2005 Front Cover: The left two photographs were taken one year apart at the same site, Big Spring Creek on Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge. The first photograph was taken in August 2004 at the time of a large horse gather on Big Spring Butte which resulted in the removal of 293 horses. These horses were placed in homes through adoption. The photograph shows the extensive damage to vegetation along the ripar- ian area caused by horses. The second photo was taken one-year later (August 2005) at the same posi- tion and angle, and shows the response of vegetation from reduced grazing pressure of horses. Woody vegetation and other responses of the ecosystem will take many years for restoration from the damage. An additional photograph on the right of the page was taken in September 2002 at Big Spring Creek. The tall vegetation was protected from grazing by the cage on the left side of the photograph. Stubble height of vegetation outside the cage was 4 cm, and 35 cm inside the cage (nearly 10 times the height). The intensity of horse grazing pressure was high until the gather in late 2004. Additional photo com- parisons are available from other riparian sites. Photo credit: FWS, David N. Johnson Department of Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service revised, final Environmental Assessment for Horse and Burro Management at Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge April 2008 Prepared by: U.S. -

We Cover the Risk So You Can Focus on the Reward

CRT - Mixed Sale February 2019 1 WE COVER THE RISK SO YOU CAN FOCUS ON THE REWARD. You’ve worked hard for your assets. Protect them against misfortune. KUDA COVERS YOUR RACEHORSE: Mortality Cover, Lifesaving Surgery and Critical Care Cover, Medical Care Cover, and Public Liability Cover. KUDA COVERS EVERYTHING ELSE: We cover all your valued assets: Personal and Commercial Insurance, Sport Horse Insurance, and Game and Wildlife Insurance. If you trust us with covering your valued thoroughbred, you can trust us to cover all your assets. CALL US TODAY FOR COVER FROM THE LUXURY LIFESTYLE INSURANCE SPECIALISTS. WÉHANN SMITH +27 82 337 4555 JO CAMPHER +27 82 334 4940 ninety9cents 42088T ninety9cents Kuda Holdings - Authorised Financial Services Provider, FSP number: 38382. All policies are on a Co-Insurance basis between Infiniti Insurance and various syndicates of Lloyds. Kuda Holdings approved Lloyds coverholder PIN 112897CJS. 2 CRT - Mixed Sale February 2019 42088T Kuda Turf Directory Print Ad Luxury lifestyle insurance 210 x 148 FA2.indd 1 2018/12/19 2:48 PM CRT - Mixed Sale February 2019 3 VENDOR INDEX Lot Colour Sex Breeding On Account of Cheveley Stud. (As Agent) 43 Chestnut Mare Oxbow Lake by Fort Wood (USA) 45 Chestnut Mare Tippuana by Fort Wood (USA) 51 Chestnut Mare Silent Treatment by Jet Master 56 Chestnut Mare Rachel Leigh by Fort Wood (USA) 70 Bay Mare Miss K by Kahal (GB) 72 Chestnut Mare Giant's Slipper (AUS) by Giant's Causeway (USA) 76 Grey Mare Ado Annie by Trippi (USA) 84 Bay Mare Lavender Bells by Al Mufti (USA) On Account of Harold Crawford Racing. -

Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines Caitlin Castaneda 1 , Rytis Juras 1, Anas Khanshour 2, Ingrid Randlaht 3, Barbara Wallner 4, Doris Rigler 4, Gabriella Lindgren 5,6 , Terje Raudsepp 1,* and E. Gus Cothran 1,* 1 College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 2 Sarah M. and Charles E. Seay Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children, Dallas, TX 75219, USA 3 Estonian Native Horse Conservation Society, 93814 Kuressaare, Saaremaa, Estonia 4 Institute of Animal Breeding and Genetics, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 75007 Uppsala, Sweden 6 Livestock Genetics, Department of Biosystems, KU Leuven, B-3001 Leuven, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (E.G.C.) Received: 9 August 2019; Accepted: 13 August 2019; Published: 20 August 2019 Abstract: The Estonian Native Horse (ENH) is a medium-size pony found mainly in the western islands of Estonia and is well-adapted to the harsh northern climate and poor pastures. The ancestry of the ENH is debated, including alleged claims about direct descendance from the extinct Tarpan. Here we conducted a detailed analysis of the genetic makeup and relationships of the ENH based on the genotypes of 15 autosomal short tandem repeats (STRs), 18 Y chromosomal single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), mitochondrial D-loop sequence and lateral gait allele in DMRT3. -

PIS the E-BARQ Questionnaire Will Take Approximately 20

05/10/2020 Qualtrics Survey Software English PIS The E-BARQ questionnaire will take approximately 20 - 30 minutes to complete. E-BARQ is voluntary and your information is confidential. If you answer all of the questions, you will receive a Share-&-Compare graph on completion. This graph will show you where your horse compares to the population on 14 different categories, including Trainability, Rideability, Social Confidence and so on. Please respond to all questions to receive your graph (which can be found on your E-BARQ dashboard (under the E-BARQ Results tab) , immediately on completion). Please click here to download the E-BARQ personal information statement. I have read and agreed to the Personal Information Statement and Terms and Conditions of the E-BARQ project. Yes No (this option will remove you from E-BARQ) https://sydney.qualtrics.com/Q/EditSection/Blocks/Ajax/GetSurveyPrintPreview?ContextSurveyID=SV_3dVyqziNawK514h&ContextLibraryID=U… 1/85 05/10/2020 Qualtrics Survey Software Your email address registered: ${e://Field/user} Is this your FIRST time completing an E-BARQ questionnaire? Select 'No' if you already have an E-BARQ Dashboard (have completed an E-BARQ for another horse). Yes No, I have completed an E-BARQ previously 1st E-BARQ Demographics Are you? In which country do you reside? https://sydney.qualtrics.com/Q/EditSection/Blocks/Ajax/GetSurveyPrintPreview?ContextSurveyID=SV_3dVyqziNawK514h&ContextLibraryID=U… 2/85 05/10/2020 Qualtrics Survey Software What is your age? Are you RIGHT or LEFT handed? Demographics Your horse's name: ${e://Field/horsename} Your horse's E-BARQ ID: ${e://Field/ebarqid} You are welcome to complete one E-BARQ for each horse that you own but this survey will refer only to the horse named here. -

Purebred Dog Breeds Into the Twenty-First Century: Achieving Genetic Health for Our Dogs

Purebred Dog Breeds into the Twenty-First Century: Achieving Genetic Health for Our Dogs BY JEFFREY BRAGG WHAT IS A CANINE BREED? What is a breed? To put the question more precisely, what are the necessary conditions that enable us to say with conviction, "this group of animals constitutes a distinct breed?" In the cynological world, three separate approaches combine to constitute canine breeds. Dogs are distinguished first by ancestry , all of the individuals descending from a particular founder group (and only from that group) being designated as a breed. Next they are distinguished by purpose or utility, some breeds existing for the purpose of hunting particular kinds of game,others for the performance of particular tasks in cooperation with their human masters, while yet others owe their existence simply to humankind's desire for animal companionship. Finally dogs are distinguished by typology , breed standards (whether written or unwritten) being used to describe and to recognize dogs of specific size, physical build, general appearance, shape of head, style of ears and tail, etc., which are said to be of the same breed owing to their similarity in the foregoing respects. The preceding statements are both obvious and known to all breeders and fanciers of the canine species. Nevertheless a correct and full understanding of these simple truisms is vital to the proper functioning of the entire canine fancy and to the health and well being of the animals which are the object of that fancy. It is my purpose in this brief to elucidate the interrelationship of the above three approaches, to demonstrate how distortions and misunderstandings of that interrelationship now threaten the health of all of our dogs and the very existence of the various canine breeds, and to propose reforms which will restore both balanced breed identity and genetic health to CKC breeds. -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Biodiversity of Arabian Horses in Syria

Biodiversity of Arabian horses in Syria Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum agriculturarum (Dr. rer. agr.) eingereicht an der Lebenswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt Universität zu Berlin von M.Sc. Saria Almarzook Präsidentin der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Sabine Kunst Dekan der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Bernhard Grimm Gutachterin/Gutachter Prof. Dr. Gudrun Brockmann Prof. Dr. Dirk Hinrichs Prof. Dr. Armin Schmitt Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 17. September 2018 Dedication This research is dedicated to my homeland …Syria Contents Zusammenfassung ................................................................................................................... I Summary ............................................................................................................................... VI List of publications and presentations .................................................................................. XII List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................ XIII List of figures ....................................................................................................................... XIV List of tables ......................................................................................................................... XV 1. General introduction and literature review ..................................................................... 1 1.1. Domestication and classification -

Horse-Breeding – Being the General Principles of Heredity

<i-. ^u^' Oi -dj^^^ LIBRARYW^OF CONGRESS. Shelf.i.S.g^. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. HORSE-BREEDING BKING THE GENERAL PRINCIPLES OE HEREDITY APPLIED TO The Business oe Breeding Horses, IXSTEUCTIOJS'S FOR THE ^IaNAGE^HKNT Stallions, Brood Mares and Young' Foals, SELECTION OF BREEDING STOCK. r y-/' J. H. SANDERS, rdiinrof 'Tlie Bleeder's Gazette," '-Breeders' Trotting Stuil Book," '•ri'r<lu Honorary member of the Chicago Eclectic Medical SoeieU>'flfti'r.> ^' Illinois Veterinary Medical Association, ^rl^.^^Ci'^'' ~*^- CHICAGO: ' ^^ J. H. SANDERS & CO. ]8S5. r w) <^ Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1885, BY J. H. SANDERS, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. ^ la TABLE OF CONTENTS. Preface 5 CHAPTER I. General Principles of Breeding.—General Laws of Heredity- Causes of Variation from Original Typos — Modifications from Changed Conditions of Life—Accidental Variations or " Sports "— Extent of Hereditary Inflaence—The Formation of Breeds—In-Breeding and Crossing—Value of Pedigree- Relative Size of Sire and Dam—Influenee of First Impregna- tion—Effect of Imagination on Color of Progeny—Effect of Change of Climate on the Generative Organs—Controlling the Sex 9 CHAPTER II. Breeds of Horses.— Thoroughbreds — Trotters and Roadsters — Orloffs or Russian Trotters—Cleveland Bays—Shire or Cart Horses—Clydesdales—Percherons-Otber Breeds (58 CHAPTER III. Stallions, Brood Mares and Foals.— Selection of Breeding- Stock—General Management of the StaUion—Controlling the Stallion When in Use—When Mares Should be Tried—The -

Morgan Horses

The 12th Annual NATIONAL MORGAN HORSE SHOW Sponsored by: Saturday Evening Friday Evening 7:00 P. M. 7:00 P. M. Sunday Saturday Afternoon Afternoon 1:00 P. M. 1:00 P. M. PERFORMANCE BREED CLASSES CLASSES For Stallions and Saddle, Harness, Mares: Colts and Pleasure. Utility Fillies and Equitation THE MORGAN HORSE CLUB Watch The Foundation Breed of America Perform. TRI-COUNTY FAIR GROUNDS NORTHAMPTON, MASS. July 30, 31 and August 1, 1954 Adults $1.00 Children - under 12 - 50' A LAW FOR IT . by 1939 Vermont Legislature "There oughta be a law agin it," is a favorite expresion of Vermonters. Sometimes they reverse themselves and make a law "for it" as they did in 1939 when the legislature passed the following resolution: "Whereas, this is the year recognized as the 150th anniversa y of the famous horse 'Justin Morgan,' which horse not only established a recognized breed of horses named for a single individual, but brought fame th•tzugh his descendants to Vermont and thousands of dollars to Vermonters. "The name Morgan has come to mean beauty, spirit, and action to all lovers of the horse; and the Morgan horses fo• many years held the world's record for trotting horses, and "Whereas the Morgan blood is recognized as foundation stock for the American Saddle Horse, for the American Trotting Horse, and for the Tennessee Walking Horse. In each of these three breeds, the Morgan horse is recognized as a foundation, and therefore, with the recognition of its value to the horse b seeders of the nation, and recognition that it was in Vermont that Morgan