Healing the Wounds of the Most Excluded Sections of Nepali Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

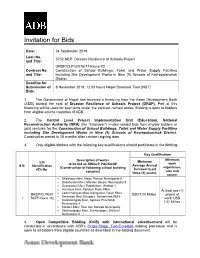

3702-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: DRSP/CLPIU/076/77-Kavre-02 Contract No

Invitation for Bids Date: 24 September 2019 Loan No. 3702-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: DRSP/CLPIU/076/77-Kavre-02 Contract No. Construction of School Buildings, Toilet and Water Supply Facilities and Title: including Site Development Works in Nine (9) Schools of Kavrepalanchok District Deadline for Submission of 8 November 2019, 12:00 hours Nepal Standard Time (NST) Bids: 1. The Government of Nepal has received a financing from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) toward the cost of Disaster Resilience of Schools Project (DRSP). Part of this financing will be used for payments under the contract named above. Bidding is open to bidders from eligible source countries of ADB. 2. The Central Level Project Implementation Unit (Education), National Reconstruction Authority (NRA) (the “Employer”) invites sealed bids from eligible bidders or joint ventures for the Construction of School Buildings, Toilet and Water Supply Facilities including Site Development Works in Nine (9) Schools of Kavrepalanchok District. Construction period is 18 months after contract signing date. 3. Only eligible bidders with the following key qualifications should participate in the bidding: Key Qualification Minimum Description of works Minimum Lot work to be bid as SINGLE PACKAGE Average Annual S.N. Identification experience, (Construction of following school building Turnover (Last (ID) No. size and complex) three (3) years). nature. • Bhaleswor Mavi, Malpi, Panauti Municipality-8 • Dedithumka Mavi, Mandan Deupur Municipality-9 • Gyaneswori Mavi, Padalichaur, Anaikot-1 • Himalaya Mavi, Pipalbot, Rosh RM-6 At least one (1) • Laxmi Narayan Mavi, Narayantar, Roshi RM-2 DRSP/CLPIU/0 USD 7.00 Million project of Saraswati Mavi, Bhugdeu, Bethanchok RM-6 1 76/77-Kavre -02 • worth USD • Sarbamangala Mavi, Aglekot, Panchkhal Municipality-3 2.52 Million. -

Proceedings of International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and Resilience for Sustainable Livelihood 12-14 January 2015 Kathmandu, Nepal

Proceedings of International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and Resilience for Sustainable Livelihood 12-14 January 2015 Kathmandu, Nepal Organizers: The Small Earth Nepal (SEN) City University of New York (CUNY), USA Colorado State University (CSU), USA Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM), Government of Nepal Nepal Academy of Science and Technology (NAST), Nepal Agriculture and Forestry University (AFU), Nepal Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC), Nepal Editors: Dr. Soni Pradhananga, University of Rhode Island, USA Jeeban Panthi, The Small Earth Nepal, Nepal Dilli Bhattarai, The Small Earth Nepal Executive Summary Climate change is one of the most crucial environmental, social, and economic issues the world is facing today. Some impacts such as increasing heat stress, more intense floods, prolonged droughts, and rising sea levels have now become inevitable. Climatic extremes are becoming more frequent; wet periods are becoming wetter and dry periods are becoming dryer. People are able to describe the impacts faced by climate change but not the meaning of „climate change‟. The impacts are most severe for the poor countries. It is high time to plan and implement adaptive measures to minimize the adverse impacts due to climate change, and it is important to explore innovative ideas and practices in building resilience for sustainable development and livelihood, particularly in rural areas of developing countries which are highly vulnerable to climate change. Climate innovation and technologies involve basic science and engineering as well as information dissemination, capacity building, and community organizing. In this context an International Conference on Climate Change Innovation and resilience for Sustainable Livelihood was held in Kathmandu, Nepal from 12-14 January 2015. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Vol 2014-01 Enlift Project Site Selection Report

Volume 2014-01 ISSN 2208-0392 RESEARCH PAPER SERIES on Agroforestry and Community Forestry in Nepal The Research Paper Series on Agroforestry and Community Forestry in Nepal is published bi-monthly by “Enhancing livelihoods and food security from agroforestry and community forestry in Nepal”, or the EnLiFT Project (http://enliftnepal.org/). EnLiFT Project is funded by the Australian Centre of International Agricultural Research (ACIAR Project FST/2011/076). EnLiFT was established in 2013 and is a collaboration between: University of Adelaide, University of New South Wales, World Agroforestry Centre, Department of Forests (Government of Nepal), International Union for Conservation of Nature, ForestAction Nepal, Nepal Agroforestry Foundation, SEARCH-Nepal, Institute of Forestry, and Federation of Community Forest Users of Nepal. This is a peer-reviewed publication. The publication is based on the research project funded by Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). Manuscripts are reviewed typically by two or three reviewers. Manuscripts are sometimes subject to an additional review process from a national advisory group of the project. The editors make a decision based on the reviewers' advice, which often involves the invitation to authors to revise the manuscript to address specific concern before final publication. For further information, contact EnLiFT: In Nepal In Australia In Australia ForestAction Nepal University of Adelaide The University of New South Wales Dr Naya Sharma Paudel Dr Ian Nuberg Dr Krishna K. Shrestha Phone: +997 985 101 5388 Phone: +61 421 144 671 Phone: +61 2 9385 1413 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2208-0392 Disclaimer and Copyright The EnLiFT Project (ACIAR FST/2011/076) holds the copyright to its publications but encourages duplication, without alteration, of these materials for non-commercial purposes. -

2015 Nepal Earthquake Response Project Putting Older People First

2015 Nepal Earthquake Response Project PUTTING OLDER PEOPLE FIRST A Special newsletter produced by HelpAge to mark the first four months of the April 2015 Earthquake CONTENTS Message from the Regional Director Editorial 1. HelpAge International in Nepal - 2015 Nepal Earthquake 1-4 Response Project (i) Unconditional Cash Transfers (UCTs) (ii) Health Interventions (iii) Inclusion- Protection Programme 2. Confidence Re-Born 5 3. Reflections from the Field 6 4. Humanitarian stakeholders working for Older People and 7-8 Persons with Disabilities in earthquake-affected districts 5. A Special Appeal to Humanitarian Agencies 9-11 Message from the Regional Director It is my great pleasure to contribute a few words to this HelpAge International Nepal e-newsletter being published to mark the four-month anniversary of the earthquake of 25 April, 2015, focusing on ‘Putting Older People First in a Humanitarian Response’. Of the eight million people in the 14 most earthquake-affected districts1, an estimated 650,000 are Older People over 60 years of age2, and are among the most at risk population in immediate need of humanitarian assistance. When factoring-in long-standing social, cultural and gender inequalities, the level of vulnerability is even higher among the 163,043 earthquake-affected older women3. In response to the earthquake, HelpAge, in collaboration with the government and in partnership with local NGOs, is implementing cash transfers, transitional shelter, health and inclusion-protection activities targeting affected Older People and their families. Furthermore, an Age and Disability Task Force-Nepal (ADTF-N)4 has been formed to highlight the specific needs and vulnerabilities of Older People and Persons with Disabilities and to put them at the centre of the earthquake recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts. -

Annual Report 2016-017

Annual Report 2016-017 Action Works Nepal (AWON) 16 July 2016 – 15 July 2017 Thapathali, Kabil Marga, House No. 37 Telephone: +977-1-4227730 Fax: +977-1-4227730 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] www.actionworksnepal.com Foreword I am pleased to present Annual Report 2016-17 for Action Works Nepal (AWON). This report provides a summary of the overall activities carried out by AWON, its achievement and budget expenditure for the period from mid-July 2016 to mid-July 2017. During this year (2016-017), AWON successfully implemented all the activities which were planned in the annual plan for this period. AWON’s objective is to improve the livelihoods of communities through humanitarian, educational, and vocational result driven programs around political, economic, social, cultural and environmental empowerment and help communities to embrace peace, growth, and sustainable development. To fulfill this objective, AWON conducted its various program (education, health, livelihood program, women/girls empowerment, disaster risk reduction & humanitarian support) in 4 districts of two provinces (3 districts Jumla, Kalikot and Mugu from Province No. 6 and Kavre from Province No. 3). AWON’s project activities were being implemented in the least developed remote region of the country facing multiple economic, political and social risks, problems and challenges. During the year-long implementation period, some major very important political changes were faced by the country from which we expect it brings a stable government and economic prosperity with holistic development of Nepal. In this scenario, we strongly believe that we can design and implement the initiatives in upcoming years which contribute to the local community to be a self-empowered and self-sustained where all kinds of discrimination are absent. -

Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal

ICIMOD Working Paper 2016/3 Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal Before After 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. ICIMOD gratefully acknowledges the support of its core donors: The Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. 2 ICIMOD Working Paper 2016/3 Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal Authors Binod Sharma, Santosh Nepal, Dipak Gyawali, Govinda Sharma Pokharel, Shahriar Wahid, Aditi Mukherji, Sushma Acharya, and Arun Bhakta Shrestha International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, June 2016 i Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2016 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. -

Nepal: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project

Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report Project Number: 51190-001 February 2020 Nepal: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project Construction of Schools in Kavrepalanchowk District (Reconstruction Phase II) Prepared by Central Level Project Implementation Unit (Education) of National Reconstruction Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 1 II. APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY IN DUE DILIGENCE ....................... 1 III. SCOPE OF LIKELY IMPACTS OF THE PROJECTS ................................... 2 A. INVOLUNTARY RESETTLEMENT .............................................................................................................................2 B. INDIGENOUS PEOPLES .............................................................................................................................................3 C. SCHOOL TEMPLE .....................................................................................................................................................3 -

Section 3 Zoning

Section 3 Zoning Section 3: Zoning Table of Contents 1. OBJECTIVE .................................................................................................................................... 1 2. TRIALS AND ERRORS OF ZONING EXERCISE CONDUCTED UNDER SRCAMP ............. 1 3. FIRST ZONING EXERCISE .......................................................................................................... 1 4. THIRD ZONING EXERCISE ........................................................................................................ 9 4.1 Methods Applied for the Third Zoning .................................................................................. 11 4.2 Zoning of Agriculture Lands .................................................................................................. 12 4.3 Zoning for the Identification of Potential Production Pockets ............................................... 23 5. COMMERCIALIZATION POTENTIALS ALONG THE DIFFERENT ROUTES WITHIN THE STUDY AREA ...................................................................................................................................... 35 i The Project for the Master Plan Study on High Value Agriculture Extension and Promotion in Sindhuli Road Corridor in Nepal Data Book 1. Objective Agro-ecological condition of the study area is quite diverse and productive use of agricultural lands requires adoption of strategies compatible with their intricate topography and slope. Selection of high value commodities for promotion of agricultural commercialization -

Mcpms Result of Lbs for FY 2065-66

Government of Nepal Ministry of Local Development Secretariat of Local Body Fiscal Commission (LBFC) Minimum Conditions(MCs) and Performance Measurements (PMs) assessment result of all LBs for the FY 2065-66 and its effects in capital grant allocation for the FY 2067-68 1.DDCs Name of DDCs receiving 30 % more formula based capital grant S.N. Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Palpa 90 150 2 Dhankuta 85 150 3 Udayapur 81 150 Name of DDCs receiving 25 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Gulmi 79 125 2 Syangja 79 125 3 Kaski 77 125 4 Salyan 76 125 5 Humla 75 125 6 Makwanpur 75 125 7 Baglung 74 125 8 Jhapa 74 125 9 Morang 73 125 10 Taplejung 71 125 11 Jumla 70 125 12 Ramechap 69 125 13 Dolakha 68 125 14 Khotang 68 125 15 Myagdi 68 125 16 Sindhupalchok 68 125 17 Bardia 67 125 18 Kavrepalanchok 67 125 19 Nawalparasi 67 125 20 Pyuthan 67 125 21 Banke 66 125 22 Chitwan 66 125 23 Tanahun 66 125 Name of DDCs receiving 20 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Terhathum 65 100 2 Arghakhanchi 64 100 3 Kailali 64 100 4 Kathmandu 64 100 5 Parbat 64 100 6 Bhaktapur 63 100 7 Dadeldhura 63 100 8 Jajarkot 63 100 9 Panchthar 63 100 10 Parsa 63 100 11 Baitadi 62 100 12 Dailekh 62 100 13 Darchula 62 100 14 Dang 61 100 15 Lalitpur 61 100 16 Surkhet 61 100 17 Gorkha 60 100 18 Illam 60 100 19 Rukum 60 100 20 Bara 58 100 21 Dhading 58 100 22 Doti 57 100 23 Sindhuli 57 100 24 Dolpa 55 100 25 Mugu 54 100 26 Okhaldhunga 53 100 27 Rautahat 53 100 28 Achham 52 100 -

A Case Study of Panchkhal Kavrepalanchowk, Nepal

Vol. 11(10), pp. 156-165, November 2018 DOI: 10.5897/JGRP2018.0704 Article Number: 113665C59143 ISSN: 2070-1845 Copyright ©2018 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Journal of Geography and Regional Planning http://www.academicjournals.org/JGRP Full Length Research Paper Spatial linkages of local market in Nepal: A case study of Panchkhal Kavrepalanchowk, Nepal Kedar Dahal Department of Geography, Tri-Chandra Multiple Campus, Kathmandu, Nepal. Received 5 August, 2018; Accepted 13 September, 2018 Market centers are the points of interactions for socio-economic functions and services. The relative importance of the market centers are largely dependent on the functional range and magnitude which includes both commercial and non-commercial functions offered by market centers. This study tries to analyze the spatial linkages of Panchkhal market, through the collection of primary data and information in December, 2016. Generally, five types of functions are identified in the market and most of them are retail shops of mixed types. Catering and occupational services have also increased in the market in the recent years. Panchkhal Market mostly depends on Banepa and Kathmandu for goods and services. Medical facilities are supplied mainly from Dhulikhel and Banepa, and occasionally from Kathmandu. Birgunj, Hetauda, Bhaktapur are main supplier points of cement, rod and chemical fertilizer. It is relatively a small market center and provides small range of goods and services to the local communities. After declaration of the municipality in 2014, its zone of influence is expanding mostly towards adjoining rural villages of north and south. Nevertheless, fluctuation of customers’ visit was also observed during the filed study. -

Too Little and Too Much Water and Development in a Himalayan Watershed

Too Little and Too Much: Water and Development in a Himalayan Watershed Editors Hans Schreier Sandra Brown Jennifer Rae MacDonald Too Little and Too Much Water and Development in a Himalayan Watershed Editors Hans Schreier Sandra Brown Jennifer Rae MacDonald Institute for Resources and Environment University of British Columbia August 2006 Copyright @ 2006 Institute for Resources and Environment (IRES) Publisher: IRES-Press, 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, B.C. V6T 1Z4, Canada Printed in Canada Allegra Print & Imaging 211 W 2nd Ave. Vancouver, B.C. V5Y 3V5 Canada The views and interpretations in this publication are those of the authors. They are not attributable to IRES or the granting agencies (IDRC or SDC) or ICIMOD. Product named does not imply promotion or legal endorsement. ni Acknowledgements We would like to thank the many people who made a major contribution to the Jhikhu Khola watershed project. These include our Nepali team members and field staff, the farmers, all national and international students and various different organizations that provided valuable input and assistance. A major recognition goes to the International Development Research Centre (IDRC, Ottawa) which in 1989 provided the initiative financial support and continued their support throughout the length of the project. Over the 16 year span we collaborated with the following IDRC project officers: Ken Riley, N. Mateo, M. Beaussart, E. Rached, Joachim Voss, Ronnie Vernooy, John, Graham, and Liz Fabjer. They all made a special effort to help us through good and bad times but a special thank you goes to John Graham who was our true supporter, advisor, and friend over the entire length the project.