The Application of State Open Meeting Laws to Email Correspondence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

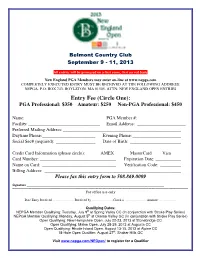

Entry Must Be Received at the Following Address: Nepga, P.O

Belmont Country Club September 9 - 11, 2013 All entries will be processed on a first come, first served basis New England PGA Members may enter on-line at www.nepga.com COMPLETELY EXECUTED ENTRY MUST BE RECEIVED AT THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS: NEPGA, P.O. BOX 743, BOYLSTON, MA 01505, ATTN: NEW ENGLAND OPEN ENTRIES Entry Fee (Circle One): PGA Professional: $350 Amateur: $250 Non-PGA Professional: $450 Name: ________________________________ PGA Member #: _____________________ Facility: _______________________________ Email Address: _____________________ Preferred Mailing Address: ___________________________________________________ Daytime Phone: _______________________ Evening Phone: _____________________ Social Sec# (required): _________________ Date of Birth: ______________________ Credit Card Information (please circle): AMEX MasterCard Visa Card Number: _________________________________ Expiration Date: ___________ Name on Card: ________________________________ Verification Code: _________ Billing Address: ___________________________________________________________ Please fax this entry form to 508.869.0009 Signature ____________________________________________________________________________________ ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- For office use only Date Entry Received ……………….. Received by ………………..Check # ……………….. Amount: ……………. Qualifying Dates: NEPGA Member Qualifying: -

2019 MASSACHUSETTS OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP June 10-12, 2019 Vesper Country Club Tyngsborough, MA

2019 MASSACHUSETTS OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP June 10-12, 2019 Vesper Country Club Tyngsborough, MA MEDIA GUIDE SOCIAL MEDIA AND ONLINE COVERAGE Media and parking credentials are not needed. However, here are a few notes to help make your experience more enjoyable. • There will be a media/tournament area set up throughout the three-day event (June 10-12) in the club house. • Complimentary lunch and beverages will be available for all media members. • Wireless Internet will be available in the media room. • Although media members are not allowed to drive carts on the course, the Mass Golf Staff will arrange for transportation on the golf course for writers and photographers. • Mass Golf will have a professional photographer – David Colt – on site on June 10 & 12. All photos will be posted online and made available for complimentary download. • Daily summaries – as well as final scores – will be posted and distributed via email to all media members upon the completion of play each day. To keep up to speed on all of the action during the day, please follow us via: • Twitter – @PlayMassGolf; #MassOpen • Facebook – @PlayMassGolf; #MassOpen • Instagram – @PlayMassGolf; #MassOpen Media Contacts: Catherine Carmignani Director of Communications and Marketing, Mass Golf 300 Arnold Palmer Blvd. | Norton, MA 02766 (774) 430-9104 | [email protected] Mark Daly Manager of Communications, Mass Golf 300 Arnold Palmer Blvd. | Norton, MA 02766 (774) 430-9073 | [email protected] CONDITIONS & REGULATIONS Entries Exemptions from Local Qualifying Entries are open to professional golfers and am- ateur golfers with an active USGA GHIN Handi- • Twenty (20) lowest scorers and ties in the 2018 cap Index not exceeding 2.4 (as determined by Massachusetts Open Championship the April 15, 2019 Handicap Revision), or who have completed their handicap certification. -

West Virginia Open History Compiled by Bob Baker

West Virginia Open History Compiled by Bob Baker 1933: Johnny Javins, the pro at Edgewood Country Club in Charleston, defeated pro I. C. ""Rocky''' Schorr of Bluefield Country Club in an 18-hole playoff at Kanawha Country Club in South Charleston to win the first West Virginia Open. Javins shot a 76 in the playoff while Schorr had an 82. They agreed to split first and second place money but Javins got the trophy donated by George C. Weimer of St. Albans. Javins and Schorr had tied after 72 holes of medal play with 302 scores. Schorr held a five-stroke lead over the field and an 11-stroke edge over Javins after two rounds but faltered on the second 36-hole day. Schorr's troubles started when he took a nine on the par-four third hole, needing five strokes to get out of a trap. Javins began his comeback with a 69 in the third round to pick up all 11 strokes on Schorr. The West Virginia Professional Golfers Association was formed in a meeting a month before the tournament, with Schorr the first president. Leaders by rounds: first, Schorr 72, by one; second, Schorr 147, by five; third, Javins and Schorr, 227s. Johnny Javins, Charleston 80-78-69-75--302 I. C. Schorr, Bluefield 72-75-80-75--302 Rader Jewett, Wheeling 81-73-77-77--308 a-Alex Larmon, Charleston 86-77-73-72--308 A. J. Chapman, Wheeling 81-82-75-74--312 Gordon Murray, Charleston 80-81-72-80--313 Kermit Hutchinson, Charleston 75-85-76-78--314 Joe Fungy, Martinsburg 73-79-80-83--315 B. -

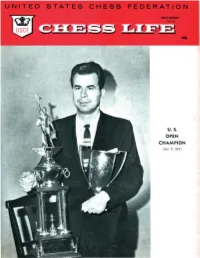

OPEN CHAMPION (See P

u. S. OPEN CHAMPION (See P. 215) Volume XIX Number \I September, lt64 EDITOR: J. F. Reinhardt U. S. TEAM TO PLAY IN ISRAEL CHESS FEDERATION The United States has formally entered a team in the 16th Chess Olympiad to be played in Tel Aviv, Israel from November 2-24 . PRESIDENT Lt. Col. E. B. Edmo ndson Invitations were sent out to the country's top playcrs In order of tbeir USCF VICE·PRESIDENT David BoUrnaDn ratings. Samuel Reshevsky, Pal Benko, Arthur Bisguier. William Addison, Dr. An thony Saidy and Donald Byrne have all accepted. Grandmaster Isaac Kashdan will REGIONAL VICE·PRESIDENTS NEW ENGLAND StaDle y Kin, accompany tbe tcam as Don-playing captain. H arold Dondl . Robert Goodspeed Unfortunately a number of our strongest players ar e missing from the team EASTERN Donald Sc hu lt ~ LewU E. Wood roster. While Lombardy, Robert Byrne and Evans were unavailable for r easons Pc)ter Berlow that had nothing to do wi th money, U. S. Cham pion Robert Fischer 's demand (or Ceoric Thoma. EII rl Clar y a $5000 fee was (ar more than the American Chess Foundation, which is raiSing Edwa rd O. S t r ehle funds for t his event, was prepared to pay. SOUTHERN Or. Noban Froe'nll:e J erry Suillyan Cu roll M. Cn lll One must assume that Fiscber, by naming 5(J large a figure and by refusing GREAT LAKES Nor bert Malthewt to compromise on it, realized full well that he was keeping himseJ! off the team Donald B. IIUdlng as surely as if be had C{)me out with a !lat "No." For more than a year Fischer "amn Schroe(ier has declined to play in international events to which he bas been invited- the NORTH CENTRAL F rank Skoff John Oane'$ Piatigorsky Tournament, the Intenonal, and now the Olympiad. -

Pgasrs2.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Senior PGA Championship RecordBernhard Langer BERNHARD LANGER Year Place Score To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money 2008 2 288 +8 71 71 70 76 $216,000.00 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 3, 8, 10, 20 2009 T-17 284 +4 68 70 73 73 $24,000.00 Totals: Strokes Avg To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money ê Birth Date: Aug. 27, 1957 572 71.50 +12 69.5 70.5 71.5 74.5 $240,000.00 ê Birthplace: Anhausen, Germany êLanger has participated in two championships, playing eight rounds of golf. He has finished in the Top-3 one time, the Top-5 one time, the ê Age: 52 Ht.: 5’ 9" Wt.: 155 Top-10 one time, and the Top-25 two times, making two cuts. Rounds ê Home: Boca Raton, Fla. in 60s: one; Rounds under par: one; Rounds at par: two; Rounds over par: five. ê Turned Professional: 1972 êLowest Championship Score: 68 Highest Championship Score: 76 ê Joined PGA Tour: 1984 ê PGA Tour Playoff Record: 1-2 ê Joined Champions Tour: 2007 2010 Champions Tour RecordBernhard Langer ê Champions Tour Playoff Record: 2-0 Tournament Place To Par Score 1st 2nd 3rd Money ê Mitsubishi Elec. T-9 -12 204 68 68 68 $58,500.00 Joined PGA European Tour: 1976 ACE Group Classic T-4 -8 208 73 66 69 $86,400.00 PGA European Tour Playoff Record:8-6-2 Allianz Champ. Win -17 199 67 65 67 $255,000.00 Playoff: Beat John Cook with a eagle on first extra hole PGA Tour Victories: 3 - 1985 Sea Pines Heritage Classic, Masters, Toshiba Classic T-17 -6 207 70 72 65 $22,057.50 1993 Masters Cap Cana Champ. -

600+ Federal, State, County, and City GIS Servers with Open Data

List of Federal ArcGIS Servers and State ArcGIS Servers and County ArcGIS Servers and City ArcGIS Servers Any Dead Links Are Fixed or Flagged Each Week By Joseph Elfelt, https://mappingsupport.com Twitter: @mappingsupport September 29, 2021 See a mistake? Have relevant information to share? Please send me an email via this contact page: https://mappingsupport.com/p2/gissurfer-about-contact.html Table of contents 1. READ ME June 2, 2021. 7 2. Donate to help fund this work. 7 3. COVID-19 GIS layers covering the USA . 7 4. World Miscellaneous Servers With Some USA Data. 9 5. USA Miscellaneous Servers . 9 6. Native American Tribes . 10 7. Federal GIS Servers . 11 8. State, Regional, County and City GIS Servers . 23 9. Washington D.C. Servers . 230 10. Multi-state planning . 230 11. Miscellaneous Regional Data . 231 12. U.S. Territories . 232 13. Environmental groups. 232 14. Canada GIS servers. 232 This report promotes public access to government data by publishing federal ArcGIS server addresses. County and city ArcGIS server addresses are included in this report with the hope that students in middle school and high school will use those local resources to help them learn about and explore geospatial data for their own backyard. As explained below, most of these server addresses were found with simple Google searches. This report is online as follows: pdf file https://mappingsupport.com/p/surf_gis/list-federal-state-county- city-GIS-servers.pdf txt file https://mappingsupport.com/p/surf_gis/list-federal-state-county-city-GIS-servers.t xt csv file https://mappingsupport.com/p/surf_gis/list-federal-state-county-city-GIS-servers.c sv All three file types are updated once per week. -

JUNE, 1959 Vol

I&e Tteovb 'Diyett Official Publication of THE NATIONAL HORSESHOE PITCHER'S ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA JUNE, 1959 Vol. 3 No. 6 Set the pace with more ringers with the 1959 model . by the original producers of a steel drop-forged pitching shoe. Furnished in Soft and Medium Hardness The OHIO SHOE with its stake holding qualities PLUS its perfect balance gives the control needed for those extra ring- ers that would have otherwise spun off. Write TODAY for prices OHIO HORSESHOE COMPANY P. O. BOX 5801 COLUMBUS 21, OHIO ill IIIIII llll Illlllllllllllllll THE HORSESHOE PITCHER'S NEWS DIGEST 3 THE HORSESHOE PITCHERS' NEWS DIGEST published on the 15th of each month at Aurora, Illinois, U.S.A. by the National Horseshoe Pitchers' Association of America. Editorial office, 1307 Solfisburg Avenue, Aurora, Illinois. Membership and subscription price $3.50 per year in advance. Forms close on the first day of each month. Advertising rates on request. F. Ellis Cobb, Editor. Volume 3 June No. 6 PRES. GREGSON OUTLINES RULES GOVERNING 1959 WORLD TOURNAMENT 1. All contestants are to have their name, town, and state lettered on their shirts to be readable at a distance of fifty feet. These are to be worn in qualifying as well as in tournament play. 2. Qualifying day is July 22. Early qualifying will be permitted on July 20 and 21, if officials are present. 3. Qualifiers will pitch 200 consecutive shoes for total points. Second try not per- mitted this year. 4. Qualifiers will pay $10.00 entry fee and present 1959 National card. -

Rare Golf Books & Memorabilia

Sale 513 August 22, 2013 11:00 AM Pacific Time Rare Golf Books & Memorabilia: The Collection of Dr. Robert Weisgerber, GCS# 128, with Additions. Auction Preview Tuesday, August 20, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, August 21, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, August 22, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor : San Francisco, CA 94108 phone : 415.989.2665 toll free : 1.866.999.7224 fax : 415.989.1664 [email protected] : www.pbagalleries.com Administration Sharon Gee, President Shannon Kennedy, Vice President, Client Services Angela Jarosz, Administrative Assistant, Catalogue Layout William M. Taylor, Jr., Inventory Manager Consignments, Appraisals & Cataloguing Bruce E. MacMakin, Senior Vice President George K. Fox, Vice President, Market Development & Senior Auctioneer Gregory Jung, Senior Specialist Erin Escobar, Specialist Photography & Design Justin Benttinen, Photographer System Administrator Thomas J. Rosqui Summer - Fall Auctions, 2013 August 29, 2013 - Treasures from our Warehouse, Part II with Books by the Shelf September 12, 2013 - California & The American West September 26, 2013 - Fine & Rare Books October 10, 2013 - Beats & The Counterculture with other Fine Literature October 24, 2013 - Fine Americana - Travel - Maps & Views Schedule is subject to change. Please contact PBA or pbagalleries.com for further information. Consignments are being accepted for the 2013 Auction season. Please contact Bruce MacMakin at [email protected]. Front Cover: Lot 303 Back Cover: Clockwise from upper left: Lots 136, 7, 9, 396 Bond #08BSBGK1794 Dr. Robert Weisgerber The Weisgerber collection that we are offering in this sale is onlypart of Bob’s collection, the balance of which will be offered in our next February 2014 golf auction,that will include clubs, balls and additional books and memo- rabilia. -

Equity Forward's Sunshine Guide: a Toolkit for State-Level Public

Equity Forward’s Sunshine Guide: A Toolkit for State-Level Public Records Research [email protected] Table of Contents Preface 5 Who We Are 5 How This Guide Came to Be 6 Public Records Research: Why Do It? 7 Examples of Success from Equity Forward’s State-Level Public Records Research 8 How to Write a Public Records Request Letter 10 Sample Public Records Request Letter 11 Tracking Public Records 13 Why, How, and When to Follow Up 13 Obstacles and How to Deal with Them 14 Reviewing Records Received 15 How to Use Findings from Public Records Research 15 Toolkit: Templates for Download 16 Request Letter Template 16 Tracking Spreadsheet Template 16 Report Template for Reviewing Records 16 Additional State FOIA Resources 16 State-Specific Submission Guidelines 17 Alabama 19 Alaska 20 Arizona 21 Arkansas 22 California 23 Colorado 24 Connecticut 25 District of Columbia 26 Delaware 27 EQUITY FORWARD SUNSHINE GUIDE 2 Florida 28 Georgia 29 Hawaii 30 Idaho 31 Illinois 32 Indiana 33 Iowa 34 Kansas 35 Kentucky 36 Louisiana 37 Maine 38 Maryland 39 Massachusetts 40 Michigan 41 Minnesota 42 Mississippi 43 Missouri 44 Montana 45 Nebraska 46 Nevada 47 New Hampshire 48 New Jersey 49 New Mexico 50 New York 51 North Carolina 52 North Dakota 53 Ohio 54 Oklahoma 55 Oregon 56 Pennsylvania 57 Rhode Island 58 EQUITY FORWARD SUNSHINE GUIDE 3 South Carolina 59 South Dakota 60 Tennessee 61 Texas 62 Utah 63 Vermont 64 Virginia 65 Washington 66 West Virginia 67 Wisconsin 68 Wyoming 69 Acknowledgements 70 EQUITY FORWARD SUNSHINE GUIDE 4 Preface Who We Are Equity Forward, founded in 2017, is a watchdog project that seeks to ensure transparency and accountability among anti-reproductive health groups and individuals. -

Bob Ackerman Jason Alexander

The 2011 PGA Professional National Championship Players' Guide —1 q Bob Ackerman BOB ACKERMAN http://www.golfobserver.com/new/golfstats.php?style=&tour=PGA&name=Bob+Ackerman&year=&tournament=PGA+Championship&in=SearchPGA Championship Record Place After Rounds Birth Date: March 27, 1953x Year 1st 2nd 3rd Place To Par Score 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money Birthplace: Benton Harbor, Mich. 1985 128 85 CUT +7 149 77 72 $1,000.00 Age: 58 1986 118 87 CUT +6 148 76 72 $1,000.00 Home: West Bloomfield, Mich. 1994 39 77 CUT +6 146 72 74 $1,200.00 College: Indiana Totals: Strokes+To Par Avg 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money Turned Professional: 1975 443 + 73.83 75.0 72.7 0.0 0.0 $3,200.00 ¢ Ackerman has participated in three PGA Championships, playing six rounds of golf. He PGA Membership: 1981 has not made a cut. Rounds in 60s: none Rounds under par: none; Rounds at par: none; ELIGIBILITY CODE: 5 Rounds over par: six ¢ Lowest Score at PGA Championship: 72 PGA Classification: MP ¢ Highest Score at PGA Championship: 77 PGA Section: Michigan PGA Master Professional, golf clinician and owner of Bob Ack- erman Golf in Bloomfield, Mich. … Missed the cut in the 2010 PGA Professional National Championship … Tied for 11th in the 2004 Northern PGA Club Professional Championship … Four-time Illinois PGA Player of the Year (1985, ’87, ’88, ’89) … Winner, 1989 Illinois Open, Illinois PGA Championship (1988, ’92), Illinois PGA Match Play Championship (1984, ’87, ’88, ’89, ’96), 1984 PGA Senior-Junior Championship (with Bill Kozak), two PGA Tournament Series events (1980, ’81), 1975 and 2003 Michigan Open. -

M" 1959·1960 Ca.Mpaig" 70 Members, Giving It a July 5 Total Only 15 Short of Its Arch·Rival on the Other Coast

• • A m l!rica ~ d ll~tJ nflW~pal"r Co pyr Ight l t60 by UnIted , t." 1 C h.n, "~""~~" ~"~'~" _______________--': ~-,;----:_ ~V~o~L~X~IV~,~N~o~,~2~3~ _ ___ __________~F~"=da=y~.~A=ug~u~'I~S~,~1~ 9 ~60~ _________ _ ______ _ ~lS~C~.~n~",- RESHEVSKY LEADS AFTER 13 OF 19 ROUNDS STUDENT TEAM LENINGRAD BOUND AT BUENOS AIRES - KORCHNOI AND UNZICKER NEXT In the invitational grandmast !;, r 10urn:lIll('nl in Bu c' nos Aires. wi th thirteen completed rounds (of ninelt'en) Samuel R(' s h evsk ~' of the USA has a slim half·point lead over Korchnoi of th e USSR and Unzicker of West Germany. In 4th place. at this stage. Larry Evans of the USA and Laruo Szabo of Hungary are lied. P;J\ Benko and Bobby Fischer, the other two USA players, have minus scores. Standing of the players aft er thirteen rounds: IV L IV L Res hcvsky ................. .... ... 9 4 ivkov ................... .. .... ...... .6 )~ 6% Korchnoi ................. ......... 8 Ih 4!f.1 Benko .................... _........ 6 7 Unzicker .......................... 8 1h 4 1h Gligol"ic .......... _.. _. _._ __ ._.... 6 7 Evans ................................8 5 Pachman ...... .................... 6 7 Szabo ................................ 8 5 Wexler ..... ___ ._.... __ . __ __.. __... 6 7 OIafsson ..........................7 1h 5* El iskases ............... ......... 5 Rossetto ..... ..................... 71h 51h Fischer ......... _................. 5 • Uhlmann ................. ..... .... 7Ih 5lh ~·os u e llllan .. __ ....... ... ,... ,.. 4 1~ •.% Guimard ... ..... ... ............... 7 6 Bazan ........................ ,. .. ....4 Taimanov ....... .................7 6 Wade ., ................... ...... .. ...2 % • • TOURNAMENT REMINDERS ~ Aug. 6-7-CINCINNATI OPEN, Parkway YMCA, Cincinnati, Ohio (CL- A strong stude nt t u m now Lonlngrlld, compet ing 71'160) Champ ionship Stud. -

JASON AICHELE COLIN AMARAL Birth Date: September 16, 1981 Birth Date: December 08, 1972 Birthplace: Richland, Wash

The 2014 PGA Professional National Championship Players' Guide —1 JASON AICHELE COLIN AMARAL Birth Date: September 16, 1981 Birth Date: December 08, 1972 Birthplace: Richland, Wash. Birthplace: Hamden, Conn. Age: 32 Age: 41 Home: Richland, Wash. Home: Port St. Lucie, Fla. College: University of Wyoming College: Georgia Southern Turned Professional: 2005 Turned Professional: 1993 PGA Membership: 2011 PGA Membership: 2001 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 5 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 5 PGA Classification: A-6 PGA Classification: A-8 PGA Section: Pacific Northwest PGA Section: Metropolitan Aichele (“Ike-Lee”) is a PGA teaching professional at Meadow PGA assistant professional at Metropolis Country Club in White Springs Country Club in Kennewick, Washington... Earned a Na- Plains, New York... Competed in National Championship five tional Championship berth by finishing fifth in the Pacific North- times, with best showing T-24 in 2008... Winner, 1997 Azores west PGA Championships... Finished third, 2008 Northwest Open in Portugal, 2004 International Club Professional Champi- Open; fifth, 2011 Washington State PGA Match Play Champion- onship, 2005 Duffys Rib Championship... Three-time winner on ship; fifth, 2010 Washington Open; third, 2008 Northwest Open... BAM tour... Winner, one event in 2006 in the PGA Tournament Played golf at the University of Wyoming, 2002-2005; competed Series; 2004 Met PGA Trieber Memorial... Winner, ‘01,’04 in every event... Caddied for current PGA Tour professional Westchester PGA Championship, 1999 Connecticut PGA Assis- David Hearn... Was 7th in 2004 NCAA Div. I for Fairways Hit... tants Championship... Finished fourth in 2005 National PGA As- Has recorded five holes-in-one, with one in competition... Also sistant Championship..