An Analysis of the Urban Life and Subjectivities in the Assamese Films of Bhabendra Nath Saikia and Jahnu Barua Minakshi Dutta, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kikon Difficult Loves CUP 2017.Pdf

NortheastIndia Can we keep thinking of Northeast India as a site of violence or of the exotic Other? NortheastIndia: A PlacerfRelations turns this narrative on its head, focusing on encounters and experiences between people and cultures, the human and the non-human world,allowing forbuilding of new relationships of friendship and amity.The twelve essaysin this volumeexplore the possibilityof a new search enabling a 'discovery' of the lived and the loved world of Northeast India fromwithin. The essays in the volume employa variety of perspectives and methodological approaches - literary, historical, anthropological, interpretative politics, and an analytical study of contemporary issues, engaging the people, cultures, and histories in the Northeast with a new outlook. In the study, theregion emerges as a place of new happenings in which there is the possibility of continuous expansionof the horizon of history and issues of currentrelevance facilitating newvoices and narratives that circulate and create bonding in the borderland of South, East and SoutheastAsia. The book willbe influentialin building scholarship on the lived experiences of the people of the Northeast, which, in turn, promises potentialities of connections, community, and peace in the region. Yasmin Saikiais Hardt-Nickachos Chair in Peace Studies and Professor of History at Arizona State University. Amit R. Baishyais Assistant Professor in the Department of English at the University of Oklahoma. Northeast India A Place of Relations Editedby Yasmin Saikia Amit R. Baishya 11�1 CAMBRIDGE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom One LibertyPlaza, 20th Floor, New York,NY 10006, USA 477 WilliamstownRoad, Port Melbourne, vie 3207, Australia 4843/24, 2nd Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, Delhi-110002, India 79 Anson Road,#06-04/06, Singapore 079906 Contents Cambridge UniversityPress is part of theUniversity of Cambridge. -

GOVT. of ASSAM Office of the Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai

GOVT. OF ASSAM Office of the Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai No: DZP/142/2008-09/ Dated- 24/06/2013 To, The Finance (Economic Affair) Assam, Dispur, Ghy-06 Sub- Regarding Information PRI List Reference No- FEA (SFC) 81/2013/5/ Dated-04-06-2013 Sir, With reference to the subject cited above, I have the honour to furnish detailed Names of President of Zilla Parishad. Anchalik Panchayat & Gaon Panchayat along with Soft & Hard Copies. This is for favour of your kind information & necessary action. You’re faithfully Chief Executive Officer Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai Memo No: - DZP/142/2008-091 Dated- 24/06/2013 Copy for favour of kind information to:- 1. The Commissioner Panchayat & Rural Development. 2. The Deputy Commissioner Darrang, Mangaldai 3. The President Darrang Zilla Parishad, Mangaldai Chief Executive Officer Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai GOVT. OF ASSAM Office of the Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai 1. Name of ZP President:- Mrs. Mohsina Khatun 2. Name AP President 1. Pub Mangaldai:-Md. Jainal Abedin 2. Sipajhar:-Ayub Ancharai 3. Dalgaon :-Raihana Sultana Ahmed 4. Pachim Mangaldai:-Priti Rekha Baruah 5. Bechimari:-Firuja Khatun Chief Executive Officer Darrang Zilla Parishad Mangaldai List of GP President SI No Name & No. of ZPC Name & No. of Name & No. of GP Name of winning AP candidate 1 6.Tengabari Ms. Padmeswari No. 1 Deka 2 Lakhimpur/Tengabari 7.Lakhimpur Mr. Lohit Ch. Sarma 3 ZPC 8.Namkhola Ms. Babita Kalita Saikia 4 No. 1 Kalaigaon 9.Buragarh Mr. Hari Ram Barua 5 AP 10.Outala Mr. Kamini Kakati Saikia 6 1.Rajapukhuri Mr. -

P. Anbarasan, M.Phil, Phd. Associate Professor Department of Mass Communication and Journalism Tezpur University Tezpur – 784028

P. Anbarasan, M.Phil, PhD. Associate Professor Department of Mass communication and Journalism Tezpur University Tezpur – 784028. Assam. [email protected] [email protected] Mobile: +91-9435381043 A Brief Profile Dr. P. Anbarasan is Associate Professor in the Dept. of Mass Communication and Journalism of Tezpur Central University. He has been teaching media and communication for the last 15 years. He specializes in film studies, culture & communication studies, and international communication. He has done his doctorate from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Earlier he had studied in University Madras and Bangalore University. Before becoming teacher he worked in All India Radio and some newspapers. He has published books on Gulf war and European Radio European identity and Culture in addition to other culture and communication research works. His interest area is media and the marginalized. 1 Work Presently Associate Professor in Mass Communication and Experience Journalism, at Tezpur central University since March 2005. Earlier worked as Lecturer in the Department of Mass communication & Journalism, Assam University, Silchar, Assam from September 2000 to March 2005. Prior to that worked as Junior officer of the Indian Information Service, from 1995 to 2000 and was posted at the Central Monitoring Service, New Delhi ( March 1995 to Sept. 2000). 2 Education Obtained PhD from at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi on the topic: “The European Union’s Cultural and Audiovisual Policy: A Discourse towards Integration beyond Borders” in 2012. Earlier completed M Phil in 1997 at Jawaharlal Nehru University on a topic, “Gulf Crisis and European Media: A study of Radio coverage and Its Impact”. -

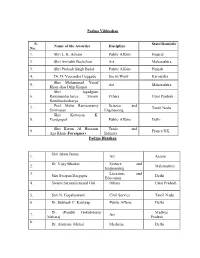

Padma Vibhushan S. No. Name of the Awardee Discipline State/Domicile

Padma Vibhushan S. State/Domicile Name of the Awardee Discipline No. 1. Shri L. K. Advani Public Affairs Gujarat 2. Shri Amitabh Bachchan Art Maharashtra 3. Shri Prakash Singh Badal Public Affairs Punjab 4. Dr. D. Veerendra Heggade Social Work Karnataka Shri Mohammad Yusuf 5. Art Maharashtra Khan alias Dilip Kumar Shri Jagadguru 6. Ramanandacharya Swami Others Uttar Pradesh Rambhadracharya Prof. Malur Ramaswamy Science and 7. Tamil Nadu Srinivasan Engineering Shri Kottayan K. 8. Venugopal Public Affairs Delhi Shri Karim Al Hussaini Trade and 9. France/UK Aga Khan ( Foreigner) Industry Padma Bhushan Shri Jahnu Barua 1. Art Assam Dr. Vijay Bhatkar Science and 2. Maharashtra Engineering 3. Literature and Shri Swapan Dasgupta Delhi Education 4. Swami Satyamitranand Giri Others Uttar Pradesh 5. Shri N. Gopalaswami Civil Service Tamil Nadu 6. Dr. Subhash C. Kashyap Public Affairs Delhi Dr. (Pandit) Gokulotsavji Madhya 7. Art Maharaj Pradesh 8. Dr. Ambrish Mithal Medicine Delhi 9. Smt. Sudha Ragunathan Art Tamil Nadu 10. Shri Harish Salve Public Affairs Delhi 11. Dr. Ashok Seth Medicine Delhi 12. Literature and Shri Rajat Sharma Delhi Education 13. Shri Satpal Sports Delhi 14. Shri Shivakumara Swami Others Karnataka Science and 15. Dr. Kharag Singh Valdiya Karnataka Engineering Prof. Manjul Bhargava Science and 16. USA (NRI/PIO) Engineering 17. Shri David Frawley Others USA (Vamadeva) (Foreigner) 18. Shri Bill Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 19. Ms. Melinda Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 20. Shri Saichiro Misumi Others Japan (Foreigner) Padma Shri 1. Dr. Manjula Anagani Medicine Telangana Science and 2. Shri S. Arunan Karnataka Engineering 3. Ms. Kanyakumari Avasarala Art Tamil Nadu Literature and Jammu and 4. -

Marginalisation, Revolt and Adaptation: on Changing the Mayamara Tradition*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 15 (1): 85–102 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2021-0006 MARGINALISATION, REVOLT AND ADAPTATION: ON CHANGING THE MAYAMARA TRADITION* BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003, Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Assam is a land of complex history and folklore situated in North East India where religious beliefs, both institutional and vernacular, are part and parcel of lived folk cultures. Amid the domination and growth of Goddess worshiping cults (sakta) in Assam, the sattra unit of religious and socio-cultural institutions came into being as a result of the neo-Vaishnava movement led by Sankaradeva (1449–1568) and his chief disciple Madhavadeva (1489–1596). Kalasamhati is one among the four basic religious sects of the sattras, spread mainly among the subdued communi- ties in Assam. Mayamara could be considered a subsect under Kalasamhati. Ani- ruddhadeva (1553–1626) preached the Mayamara doctrine among his devotees on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river. Later his inclusive religious behaviour and magical skill influenced many locals to convert to the Mayamara faith. Ritu- alistic features are a very significant part of Mayamara devotee’s lives. Among the locals there are some narrative variations and disputes about stories and terminol- ogies of the tradition. Adaptations of religious elements in their faith from Indig- enous sources have led to the question of their recognition in the mainstream neo- Vaishnava order. In the context of Mayamara tradition, the connection between folklore and history is very much intertwined. Therefore, this paper focuses on marginalisation, revolt in the community and narrative interpretation on the basis of folkloristic and historical groundings. -

Final Shortlisted Hospital Administrator

Provisionally shortlisted candidates for Interview for the Post of Hospital Administrator under NHM, Assam Instruction: Candidates shall bring all relevant testimonials and experience certificates in original to produce before selection committee along with a set of self attested photo copies for submission at the time of interview. Shortlisting of candidates have been done based on the information provided by the candidates and candidature is subject to verification of documents at the time of interview. Date of Interview : 23/10/2018 Time of Interview : 11:00 AM (Reporting Time - 10:00 AM) Venue : Office of the Mission Director, NHM, Assam, Saikia Commercial Complex, Christianbasti, Guwahati-5 Sl Regd. ID Candidate Name Father Name Address No. PARTHAJIT C/o-HARANIDHI CHAKRABORTY, H.No.-27, Vill/Town- NHM/HPTLA/0 ABHISHEK 1 BHATTACHARY ARJYAPATTY NEAR DURGA BARI, P.O.-SILCHAR, P.S.- 016 BHATTACHARYA A SILCHAR, Dist.-Cachar, State-ASSAM, Pin-788001 C/o-Amit Rajpal, H.No.-1-GHA-18, Mnumarg, Al;war, NHM/HPTLA/0 Dr. Arjun Singh 2 Amit Rajpal Vill/Town-Alwar, P.O.-HPO, Alwar, P.S.-Kotwali, Alwar, 005 Rajpal Dist.-Alwar, State-Rajasthan, Pin-301001 C/o-DR. MUNINDRA MALAKAR, H.No.-56, Vill/Town-DR. NHM/HPTLA/0 NIMAICHAND ZAKIR HUSSAIN PATH, NEAR DOWN TOWN 3 ARYA THOUDAM 017 THOUDAM HOSPITAL., P.O.-DISPUR, P.S.-DISPUR, Dist.-Kamrup Metro, State-ASSAM, Pin-781006 C/o-TIRTHA KONWAR, H.No.-Rangoli bam path, Vill/Town- NHM/HPTLA/0 BHASKAR JYOTI TIRTHA 4 SIVASAGAR, P.O.-SIMALUGURI, P.S.-SIMALUGURI, 012 KONWAR KONWAR Dist.-Sivasagar, State-ASSAM, -

Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia: a Versatile Legend of Assam

PROTEUS JOURNAL ISSN/eISSN: 0889-6348 DR. BHABENDRA NATH SAIKIA: A VERSATILE LEGEND OF ASSAM NilakshiDeka1 Prarthana Dutta2 1 Research Scholar, Department of Assamese, MSSV, Nagaon. 2 Ex - student, Department of Assamese, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh. Abstract:The versatile personality is generally used to refer to individuals with multitalented with different areas. Dr. BhabendraNathSaikia was one of the greatest legends of Assam. This multi-faceted personality has given his tits and bits to both the Assamese literature, as well as, Assamese cinema. Dr. BhabendraNathSaikia was winner of Sahitya Academy award and Padma shri, student of science, researcher, physicist, editor, short story writer and film director from Assam. His gift to the Assamese society and in the fields of art, culture and literature has not yet been adequately measured.Saikia was a genius person of exceptional intellectual creative power or other natural ability or tendency. In this paper, author analyses the multi dimension of BhabendraNathSaikias and his outstanding contributions to make him a versatile legendary of Assam. Keywords: versatile, legend, cinema, literature, writer. 1. METHODOLOGY During the research it collected data through secondary sources like various Books, E-books, Articles, and Internet etc. 2. INTRODUCTION BhabendraNathSaikia was an extraordinary talented genius ever produced by Assam in centuries. Whether it is literature or cinema, researcher or academician, VOLUME 11 ISSUE 9 2020 http://www.proteusresearch.org/ Page No: 401 PROTEUS JOURNAL ISSN/eISSN: 0889-6348 BhabendraNathSaikia was unbeatable throughout his life. The one name that coinsures up a feeling of warmth in every Assamese heart is that of Dr. BhabendraNathSaikia. 3. EARLY LIFE, EDUCATION AND CAREER BhabendranathSaikia was born on February 20, 1932, in Nagaon, Assam. -

The Lockdown to Contain the Coronavirus Outbreak Has Disrupted Supply Chains. One Crucial Chain Is Delivery of Information and I

JOURNALISM OF COURAGE SINCE 1932 The lockdown to contain the coronavirus outbreak has disrupted supply chains. One crucial chain is delivery of information and insight — news and analysis that is fair and accurate and reliably reported from across a nation in quarantine. A voice you can trust amid the clanging of alarm bells. Vajiram & Ravi and The Indian Express are proud to deliver the electronic version of this morning’s edition of The Indian Express to your Inbox. You may follow The Indian Express’s news and analysis through the day on indianexpress.com DAILY FROM: AHMEDABAD, CHANDIGARH, DELHI, JAIPUR, KOLKATA, LUCKNOW, MUMBAI, NAGPUR, PUNE, VADODARA JOURNALISM OF COURAGE THURSDAY, AUGUST 20, 2020, NEW DELHI, LATE CITY, 18 PAGES SINCE 1932 `6.00 (`8 PATNA &RAIPUR, `12 SRINAGAR) WWW.INDIANEXPRESS.COM Constitution STATE OF THE PANDEMIC TRACKING INDIA’S COVID CURVE Bench must Hopeinnumbers:Dailycasesstablefor 170 CASES: RECOVERED:20,37,870 DAYSSINCE 27,67,273 DEATHS:52,889 hear Bhushan PANDEMIC case: ex-SC BEGAN TESTS: 3,17,42,782 | DOUBLING RATE: 28.92** judge Joseph twoweeks,testsshowfewerpositives Newcases rangearound 60,000; R-value at all-timelow NEARFLATGROWTHINNEW OVERALLPOSITIVITYRATE CASESINLASTTWOWEEKS TotalPositive/Total Tested Forthe firsttime since May, fallen to 8.72per cent. KEYSTATES TOTAL SURGEIN 7-DAYAVG DOUBLING AMITABHSINHA the overall positivity rate in the Simultaneously—and not TOWATCH CASES 24HOURS GROWTH* TIME** ‘If justiceis 80000 10 PUNE,AUGUST19 countryhas begun to decline. unrelatedly —there is arelative notdone 70000 Whichmeans,for thesame stagnation in the numbers of ■ Maharashtra 6,15,477 11,119 2.01% 35.90 60000 8 heavens will SIX MONTHS afterthe outbreak number of tests,fewer people newpositive cases being de- ■ Tamil Nadu 3,49,654 5,709 1.80% 40.05 certainly fall’ 50000 of the novelcoronavirus epi- arenow beingfound infected tected everyday.This number CENT ■ Andhra 3,06,261 9,652 3.27% 22.04 40000 6 demic —and over 27 lakh cases with the virus. -

A Study of Neorealism in Assamese Cinema

A Study of Neorealism in Assamese Cinema INDRANI BHARADWAJ Registered Number: 1424030 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication and Media Studies CHRIST UNIVERSITY Bengaluru 2016 Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Media Studies ii CHRIST UNIVERSITY Department of Media Studies This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a master’s thesis by Indrani Bharadwaj Registered Number: 1424030 and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Committee Members: _____________________________________________________ [AASITA BALI] _____________________________________________________ Date: __________________________________ iii iv I, Indrani Bharadwaj, confirm that this dissertation and the work presented in it are original. 1. Where I have consulted the published work of others this is always clearly attributed. 2. Where I have quoted from the work of others the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations this dissertation is entirely my own work. 3. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. 4. If my research follows on from previous work or is part of a larger collaborative research project I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. 5. I am aware and accept the penalties associated with plagiarism. Date: v vi CHRIST UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT A Study of Neorealism in Assamese Cinema Indrani Bharadwaj The following study deals with the relationship between Assamese Cinema and its connection to Italian Neorealism. Assamese Cinema was founded in 1935 when Jyoti Prasad Agarwala released his first film “Joymoti”. -

District-Wise Number of Present Incumbents of Home Guards Name of Name of Name of the Home Gender Male/ Sl

District-wise number of present Incumbents of Home Guards Name of Name of Name of the Home Gender Male/ Sl. No. Father's Name Date of Birth Remarks if any the State the Dist. Guards Female [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] 5544 Assam Sivasagar Hema Gogoi Lt.Tankeswar Gogoi 20-10-1976 Male 5545 Assam Sivasagar Bikash Nath Khogeswar Nath 01-02-1976 Male 5546 Assam Sivasagar Jatin Baruah Prabhat Baruah 01-10-1983 Male 5547 Assam Sivasagar Bhupen Baruah Noreswar Baruah 15-03-1976 Male 5548 Assam Sivasagar Horen Gogoi Lt.Mohan Gogoi 30-12-1981 Male 5549 Assam Sivasagar Ananta Saikia Lt.Jugen Saikia 26-05-1970 Male 5550 Assam Sivasagar Ranjit Phukan Lt.Mohendra Phukan 01-11-1976 Male 5551 Assam Sivasagar Horen gogoi Lt.Jiten Gogoi 01-05-1981 Male 5552 Assam Sivasagar Ananda Dutta Minik Dutta 01-03-1987 Male 5553 Assam Sivasagar Bijit Chutia Ganesh Chutia 01-01-1984 Male 5554 Assam Sivasagar Naba Jyoti Nath Radhika Nath 30-09-1982 Male 5555 Assam Sivasagar Krishna Das Belat Das 31-12-1979 Male 5556 Assam Sivasagar Pranab Nath Dimbeswar Nath 30-10-1982 Male 5557 Assam Sivasagar Horen Borah Lt.Sonai Borah 01-10-1976 Male 5558 Assam Sivasagar Ramen Bhuyan Lt.Jugai Bhuyan 01-10-1985 Male 5559 Assam Sivasagar Durlav Saikia Biren Saikia 28-10-1989 Male 5560 Assam Sivasagar Prabhat Dutta Lt.Jatiram Dutta 01-03-1974 Male 5561 Assam Sivasagar Nitu Borah Thankeswar Borah 30-11-1983 Male 5562 Assam Sivasagar Bidyut Bikash Nath Prmod Ch Nath 30-06-1986 Male 5563 Assam Sivasagar Robin Das Pradip Das 05-03-1983 Male 5564 Assam Sivasagar Monoj Gogoi Lt. -

An Introduction to the Sattra Culture of Assam: Belief, Change in Tradition

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 12 (2): 21–47 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2018-0009 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SATTRA CULT URE OF ASSAM: BELIEF, CHANGE IN TRADITION AND CURRENT ENTANGLEMENT BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In 16th-century Assam, Srimanta Sankaradeva (1449–1568) introduced a move- ment known as eka sarana nama dharma – a religion devoted to one God (Vishnu or Krishna). The focus of the movement was to introduce a new form of Vaishnava doctrine, dedicated to the reformation of society and to the abolition of practices such as animal sacrifice, goddess worship, and discrimination based on caste or religion. A new institutional order was conceptualised by Sankaradeva at that time for the betterment of human wellbeing, which was given shape by his chief dis- ciple Madhavadeva. This came to be known as Sattra, a monastery-like religious and socio-cultural institution. Several Sattras were established by the disciples of Sankaradeva following his demise. Even though all Sattras derive from the broad tradition of Sankaradeva’s ideology, there is nevertheless some theological seg- mentation among different sects, and the manner of performing rituals differs from Sattra to Sattra. In this paper, my aim is to discuss the origin and subsequent transformations of Sattra as an institution. The article will also reflect upon the implication of traditions and of the process of traditionalisation in the context of Sattra culture. I will examine the power relations in Sattras: the influence of exter- nal forces and the support of locals to the Sattra authorities. -

Actual and Ideal Fertility Differential Among Natives, Immigrants, and Descendants of Immigrants in a Northeastern State of India

Accepted: 24 January 2019 DOI: 10.1002/psp.2238 RESEARCH ARTICLE Actual and ideal fertility differential among natives, immigrants, and descendants of immigrants in a northeastern state of India Nandita Saikia1,2 | Moradhvaj2 | Apala Saha2,3 | Utpal Chutia4 1 World Population Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Abstract Laxenburg, Austria Little research has been conducted on the native‐immigrant fertility differential in 2 Centre for the Study of Regional low‐income settings. The objective of our paper is to examine the actual and ideal fer- Development, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi, India tility differential of native and immigrant families in Assam. We used the data from a 3 Department of Geography, Institute of primary quantitative survey carried out in 52 villages in five districts of Assam during Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, 2014–2015. We performed bivariate analysis and used a multilevel mixed‐effects lin- India 4 Department of Anthropology, Delhi ear regression model to analyse the actual and ideal fertility differential by type of vil- University, Delhi, India lage. The average number of children ever‐born is the lowest in native villages in Correspondence contrast to the highest average number of children ever‐born in immigrant villages. Dr. Nandita Saikia, Post Doc Scholar, The likelihood of having more children is also the highest among women in immigrant International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Schlossplatz 1, 2361 Laxenburg, villages. However, the effect of religion surpasses the effect of the type of village the Austria. women reside in. Email: [email protected] Funding information KEYWORDS Indian Council of Social Science Research, Assam, fertility, immigrants, India, native, religion Grant/Award Number: RESPRO/58/2013‐14/ ICSSR/RPS 1 | INTRODUCTION fertility of immigrants and their descendants can be an important indi- cator of social integration over time (Dubuc, 2012).