Evaluation of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit - Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remarks on Henry Friendly

REMARKS ON HENRY FRIENDLY ON THE AWARD OF THE HENRY FRIENDLY MEDAL TO JUSTICE SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR Pierre N. Leval † RESIDENT RAMO CALLED ME a couple of days ago with a problem. Young people today (and this includes young- sters up to the age of 50) apparently do not know who Henry Friendly was or why the American Law Institute Pawards a medal in his name. Would I address those questions to- night? At first I was astonished by Roberta’s proposition. Friendly was revered as a god in the federal courts from 1958 to his death in 1986. In every area of the law on which he wrote, during a quarter century on the Second Circuit, his were the seminal and clarifying opinions to which everyone looked as providing and explaining the standards. Most of us who earn our keep by judging can expect to be de- servedly forgotten within weeks after we kick the bucket or hang up the robe and move to Florida. But for one whose judgments played † Pierre Leval is a Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. He delivered these remarks on October 20, 2011, at a dinner of the Council of the American Law Insti- tute. Copyright © 2012 Pierre N. Leval. 15 GREEN BAG 2D 257 Pierre N. Leval such a huge role, it is quite surprising – and depressing – that the memory of him has so rapidly faded. Later, a brief exploration why this might be so. I begin by recounting, for any who don’t know, what some pur- ple-robed eminences of the law have said about Friendly. -

The Seventh Circuit As a Criminal Court: the Role of a Federal Appellate Court in the Nineties

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 67 Issue 1 Symposium on the Seventh Circuit as a Article 2 Criminal Court April 1991 Foreword: The Seventh Circuit as a Criminal Court: The Role of a Federal Appellate Court in the Nineties Adam H. Kurland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Adam H. Kurland, Foreword: The Seventh Circuit as a Criminal Court: The Role of a Federal Appellate Court in the Nineties, 67 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 3 (1991). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol67/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. FOREWORD: THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT AS A CRIMINAL COURT: THE ROLE OF A FEDERAL APPELLATE COURT IN THE NINETIES ADAM H. KURLAND* I. INTRODUCTION In the spring of 1991, a highly publicized debate ensued over whether United States District Court Judge Kenneth Ryskamp should be elevated to sit on the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. The nomination was defeated in the Senate Judiciary Committee amidst echoes of partisan recrimination.' Some Republican Senators protested loudly that Ryskamp's rejection was grounded in the most base form of partisan politics-that the Eleventh Circuit was perhaps the last federal court that, despite a steady infusion over the last decade of con- servative appointments, had not yet obtained a solid conservative major- ity, and that Ryskamp's rejection was designed solely to delay that 2 eventuality. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Aviation Law Mark A

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 48 | Issue 2 Article 13 1983 Aviation Law Mark A. Dombroff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Mark A. Dombroff, Aviation Law, 48 J. Air L. & Com. 453 (1983) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol48/iss2/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. Book Reviews AVIATION LAW by Andreas F. Lowenfeld. New York: Matthew Bender & Co., 1981 Edition. pp. 1411. In 1972, Andreas Lowenfeld published the first edition of AVIATION LAW.' In the introduction to that book, Professor Lowenfeld related the challenge presented by Judge Henry Friendly: Some years ago, Judge Henry Friendly, who made his career in large part as a brilliant and imaginative general counsel for Pan American World Airways, reviewed an earlier attempt to collect materials on aviation law by asking whether it made sense to treat this subject at all. "In order to make out a case for separate treatment," he wrote, "it must be shown that the heads of a given subject can be examined in a more illuminating fashion with reference to each other than with references to other branches of law." With respect to the book under review, Judge Friendly's answer was "a resounding no."' Professor Lowenfeld went on to accept the challenge and in the seven chapters of the first edition of AVIATION LAW presented the reader with an overview of the economic, regulatory, tort, and social considerations that have grown up in the law relating to the aviation industry. -

Potential Effects of a Flat Federal Income Tax in the District of Columbia

S. HRG. 109–785 POTENTIAL EFFECTS OF A FLAT FEDERAL INCOME TAX IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SPECIAL HEARINGS MARCH 8, 2006—WASHINGTON, DC MARCH 30, 2006—WASHINGTON, DC Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27–532 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri TOM HARKIN, Iowa MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland CONRAD BURNS, Montana HARRY REID, Nevada RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HERB KOHL, Wisconsin JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire PATTY MURRAY, Washington ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois MIKE DEWINE, Ohio TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana WAYNE ALLARD, Colorado J. KEITH KENNEDY, Staff Director TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas, Chairman MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana WAYNE ALLARD, Colorado RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi (ex officio) ROBERT C. -

Judical Stratification and the Reputations of the United States Courts of Appeals

Florida State University Law Review Volume 32 Issue 4 Article 14 2005 Judical Stratification and the Reputations of the United States Courts of Appeals Michael E. Solimine [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael E. Solimine, Judical Stratification and the Reputations of the United States Courts of Appeals, 32 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. (2006) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol32/iss4/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW JUDICAL STRATIFICATION AND THE REPUTATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS Michael E. Solimine VOLUME 32 SUMMER 2005 NUMBER 4 Recommended citation: Michael E. Solimine, Judical Stratification and the Reputations of the United States Courts of Appeals, 32 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 1331 (2005). JUDICIAL STRATIFICATION AND THE REPUTATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS MICHAEL E. SOLIMINE* I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................. 1331 II. MEASURING JUDICIAL REPUTATION, PRESTIGE, AND INFLUENCE: INDIVIDUAL JUDGES AND MULTIMEMBER COURTS ............................................................... 1333 III. MEASURING THE REPUTATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS . 1339 IV. THE RISE AND FALL OF -

Judicial Genealogy (And Mythology) of John Roberts: Clerkships from Gray to Brandeis to Friendly to Roberts

The Judicial Genealogy (and Mythology) of John Roberts: Clerkships from Gray to Brandeis to Friendly to Roberts BRAD SNYDER* During his Supreme Court nomination hearings, John Roberts idealized and mythologized the first judge he clerkedfor, Second Circuit Judge Henry Friendly, as the sophisticated judge-as-umpire. Thus far on the Court, Roberts has found it difficult to live up to his Friendly ideal, particularlyin several high-profile cases. This Article addresses the influence of Friendly on Roberts and judges on law clerks by examining the roots of Roberts's distinguishedyet unrecognized lineage of former clerks: Louis Brandeis 's clerkship with Horace Gray, Friendly's clerkship with Brandeis, and Roberts's clerkships with Friendly and Rehnquist. Labeling this lineage a judicial genealogy, this Article reorients clerkship scholarship away from clerks' influences on judges to judges' influences on clerks. It also shows how Brandeis, Friendly, and Roberts were influenced by their clerkship experiences and how they idealized their judges. By laying the clerkship experiences and career paths of Brandeis, Friendly, and Roberts side-by- side in detailed primary source accounts, this Article argues that judicial influence on clerks is more professional than ideological and that the idealization ofjudges and emergence of clerks hips as must-have credentials contribute to a culture ofjudicial supremacy. * Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School. Thanks to Eleanor Brown, Dan Ernst, David Fontana, Abbe Gluck, Dirk Hartog, Dan -

Seventh Circuit Review

SEVENTH CIRCUIT REVIEW www.kentlaw.edu/7cr Volume 3, Issue 1 Fall 2007 CONTENTS Masthead iv About the SEVENTH CIRCUIT REVIEW v Bankruptcy Who’s Left Suspended on the Line?: The Ominous Hanging Paragraph and the Seventh Circuit’s Interpretation in In re Wright Simone Jones 1 Civil Procedure Outer Marker Beacon: The Seventh Circuit Confirms the Contours of Federal Question Jurisdiction in Bennett v. Southwest Airlines Co. William K. Hadler 22 Civil Rights Determining Whether Plaintiff Prevailed is a “Close Question”—But Should It Be? Nikolai G. Guerra 58 Criminal Law Missing the Forest for the Trees: The Seventh Circuit’s Refinement of Bloom’s Private Gain Test for Honest Services Fraud in United States v. Thompson Robert J. Lapointe 86 i Due Process – Familial Rights Familia Interruptus: The Seventh Circuit’s Application of the Substantive Due Process Right of Familial Relations Scott J. Richard 140 Employment Discrimination The Politics of Reversal: The Seventh Circuit Reins in a District Court Judge’s Wayward Employment Discrimination Decisions Timothy Wright 168 FDA Regulations No More Imports: Seventh Circuit Decision in United States v. Genendo is an Expensive Pill for American Consumers to Swallow Nicole L. Little 209 Federal False Claims Act “Based Upon” and the False Claims Act’s Qui Tam Provision: Reevaluating the Seventh Circuit’s Method of Statutory Interpretation Antonio J. Senagore 244 Federal Thrift Regulation Cracking the Door to State Recovery from Federal Thrifts Daniel M. Attaway 275 ii Fourth Amendment Probationers, Parolees and DNA Collection: Is This “Justice for All”? Jessica K. Fender 312 Krieg v. Seybold: The Seventh Circuit Adopts a Bright Line in Favor of Random Drug Testing Dana E. -

Oral History of Distinguished American Judges: HON. DIANE P

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW – INSTITUTE OF JUDICIAL ADMINISTRATION (IJA) Oral History of Distinguished American Judges HON. DIANE P. WOOD U.S. COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT An Interview with Steven Art, Loevy & Loevy Katherine Minarik, cleverbridge September 27, 2018 All rights in this oral history interview belong to New York University. Quoting or excerpting of this oral history interview is permitted as long as the quotation or excerpt is limited to fair use as defined by law. For quotations or excerpts that exceed fair use, permission must be obtained from the Institute of Judicial Administration (IJA) at, Wilf Hall, 139 Macdougal Street, Room 420, New York 10012, or to [email protected], and should identify the specific passages to be quoted, intended use, and identification of the user. Any permission granted will comply with agreements made with the interviewees and/or interviewers who participated in this ora l history. All permitted uses must cite and give proper credit to: IJA Oral History of Distinguished American Judges, Institute of Judicial Administration, NYU School of Law, Judge Diane P. Wood: An Interview with Steven Art and Katherine Minarik, 2018. *The transcript shall control over the video for any permitted use in accordance with the above paragraph. Any differences in the transcript from the video reflect post-interview clarifications made by the participants and IJA. The footnotes were added by IJA solely for the reader’s information; no representation is made as to the accuracy or completeness of any of such footnote s. Transcribed by Ubiqus www.ubiqus.com NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW – INSTITUTE OF JUDICIAL ADMINISTRATION (IJA) Oral History of Distinguished American Judges [START RECORDING] MS. -

Circuit Circuit

April 2011 Featured In This Issue Jerold S. Solovy: In Memoriam, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole TheThe A Celebration of 35 Years of Judicial Service: Collins Fitzpatrick’s Interview of Judge John Grady, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole Great Expectations Meet Painful Realities (Part I), By Steven J. Harper The 2010 Amendments to Rule 26: Limitations on Discovery of Communications Between CirCircuitcuit Lawyers and Experts, By Jeffrey Cole The 2009 Amendments to Rule 15(a)- Fundamental Changes and Potential Pitfalls for Federal Practitioners, By Katherine A. Winchester and Jessica Benson Cox Object Now or Forever Hold Your Peace or The Unhappy Consequences on Appeal of Not Objecting in the District Court to a Magistrate Judge’s Decision, By Jeffrey Cole RiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH Some Advice on How Not to Argue a Case in the Seventh Circuit — Unless . You’re My Rider Adversary, By Brian J. Paul C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Certification and Its Discontents: Rule 23 and the Role of Daubert, By Catherine A. Bernard Recent Changes to Rules Governing Amicus Curiae Disclosures, By Jeff Bowen C h a n g e s The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . .1 Jerold S. Solovy: In Memoriam, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole . ... 2-5 A Celebration of 35 Years of Judicial Service: Collins Fitzpatrick’s Interview of Judge John Grady, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole . 6-23 Great Expectations Meet Painful Realities (Part I), By Steven J. Harper . 24-29 The 2010 Amendments to Rule 26: Limitations on Discovery of Communications Between Lawyers and Experts, By Jeffrey Cole . -

Previously Released Merrick Garland Docs

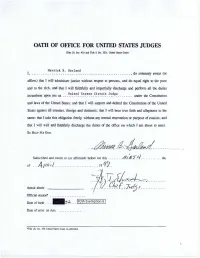

OATH OF OFFICE FOR UNITED STATES JUDGES (ritlc 28, Sec. 453 and Title 5. Sec. 3331. Unltr.d St.aleS Code) Merrick B. Garland I, ...... ............. .. .............. ....... .......... , do solemnly swear (or affinn) that I will administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich, and that I will faithfully and impartially discharge and perfonn all the duties . United States Circuit Judge . incumbent upon me as . under the Consucuuon and laws of the United States: and that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic: that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same: that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion: and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So HELP ME Goo. ... ..... u ~~- UL ... .·------_ Subscribed and swo ~ to (or affinned) before me this ....... Al.I. R '.T ~f.. ..... ... ... day of .. 4,pJ? .; ) .. ..................... 19 f.7 . -~ - ~~dL~-~~i ··· .. ..... Actual abode .... .. .< .~'- ~ { :- ~ 11J .~ ...... ..... ... Official station* ........... ...... Date of binh ... · · ·~?:- ... I~<?!~ Exemption 6 I Date of entry on duty .. ... ........ "'Titk lll S<?c. -1~6 u nited St.ate~ Code. as amended. v .o. \.JI·~ Of r"9'110tW'191 Menagemef'W FPM CMplllr IZle et-toe APPOINTMENT AFFIDAVITS United States Circuit Judge March 20, 1997 (POfition to wlticl appoif!Ud) (Dau o/ appoin~ U. S. Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit, Washington, DC (BuNau or Divilion) (Plau of tmp~t) Merrick B. Garland I, ----------------------• do solemnly swear (or affirm) that- A. -

Choosing the Next Supreme Court Justice: an Empirical Ranking of Judicial Performance†

Choosing the Next Supreme Court Justice: † An Empirical Ranking of Judicial Performance Stephen Choi* ** Mitu Gulati † © 2004 Stephen Choi and Mitu Gulati. * Roger J. Traynor Professor, U.C. Berkeley Law School (Boalt Hall). ** Professor of Law, Georgetown University. Kindly e-mail comments to [email protected] and [email protected]. Erin Dengan, Édeanna Johnson-Chebbi, Margaret Rodgers, Rishi Sharma, Jennifer Dukart, and Alice Kuo provided research assistance. Kimberly Brickell deserves special thanks for her work. Aspects of this draft benefited from discussions with Alex Aleinikoff, Scott Baker, Lee Epstein, Tracey George, Prea Gulati, Vicki Jackson, Mike Klarman, Kim Krawiec, Kaleb Michaud, Un Kyung Park, Greg Mitchell, Jim Rossi, Ed Kitch, Paul Mahoney, Jim Ryan, Paul Stefan, George Triantis, Mark Seidenfeld, and Eric Talley. For comments on the draft itself, we are grateful to Michael Bailey, Suzette Baker, Bill Bratton, James Brudney, Steve Bundy, Brannon Denning, Phil Frickey, Michael Gerhardt, Steve Goldberg, Pauline Kim, Bill Marshall, Don Langevoort, Judith Resnik, Keith Sharfman, Steve Salop, Michael Seidman, Michael Solimine, Gerry Spann, Mark Tushnet, David Vladeck, Robin West, Arnold Zellner, Kathy Zeiler, Todd Zywicki and participants at workshops at Berkeley, Georgetown, Virginia, FSU, and UNC - Chapel Hill. Given the unusually large number of people who have e-mailed us with comments on this project, it is likely that there are some who we have inadvertently failed to thank. Our sincerest apologies to them. Disclosure: Funding for this project was provided entirely by our respective law schools. One of us was a law clerk to two of the judges in the sample: Samuel Alito of the Third Circuit and Sandra Lynch of the First Circuit.