Martí Tomàs2016.Pdf (1.792Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claiming Independence in 140 Characters. Uses of Metaphor in the Construction of Scottish and Catalan Political Discourses on Twitter

CLAIMING INDEPENDENCE IN 140 CHARACTERS. USES OF METAPHOR IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF SCOTTISH AND CATALAN POLITICAL DISCOURSES ON TWITTER Carlota Maria Moragas Fernández ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. -

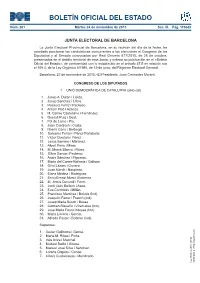

Boletín Oficial Del Estado

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 281 Martes 24 de noviembre de 2015 Sec. III. Pág. 110643 JUNTA ELECTORAL DE BARCELONA La Junta Electoral Provincial de Barcelona, en su reunión del día de la fecha, ha acordado proclamar las candidaturas concurrentes a las elecciones al Congreso de los Diputados y al Senado convocadas por Real Decreto 977/2015, de 26 de octubre, presentadas en el ámbito territorial de esta Junta, y ordena su publicación en el «Boletín Oficial del Estado», de conformidad con lo establecido en el artículo 47.5 en relación con el 169.4, de la Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General. Barcelona, 23 de noviembre de 2015.–El Presidente, Joan Cremades Morant. CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS 1. UNIÓ DEMOCRÀTICA DE CATALUNYA (unio.cat) 1. Josep A. Duran i Lleida. 2. Josep Sanchez i Llibre. 3. Rosaura Ferriz i Pacheco. 4. Antoni Picó i Azanza. 5. M. Carme Castellano i Fernández. 6. Queralt Puig i Gual. 7. Pol de Lamo i Pla. 8. Joan Contijoch i Costa. 9. Noemi Cano i Berbegal. 10. Salvador Ferran i Pérez-Portabella. 11. Víctor Gonzalo i Pérez. 12. Jesús Serrano i Martínez. 13. Albert Peris i Miras. 14. M. Mercè Blanco i Ribas. 15. Sílvia Garcia i Pacheco. 16. Anaïs Sánchez i Figueras. 17. Maria del Carme Ballesta i Galiana. 18. Oriol Lázaro i Llovera. 19. Joan March i Naspleda. 20. Elena Medina i Rodríguez. 21. Enric-Ernest Munt i Gutierrez. 22. M. Jesús Cucurull i Farré. 23. Jordi Lluís Bailach i Aspa. 24. Eva Cordobés i Millán. -

ERC Llista Sencera

Membres de la Llista electoral d’Esquerra Republicana-Moviment d’Esquerres-BCN Ciutat Oberta- Avancem-Catalunya Sí a Barcelona • Alfred Bosch (Catalunya Sí) • Juanjo Puigcorbé (Catalunya Sí) • Montserrat Benedí (ERC) • Trini Capdevila (ERC) • Jordi Coronas (ERC) • Gemma Sendra (MES) • Jordi Castellana (ERC) • Carles Manel Macian (ERC) • Miquel Pagès (ERC) • Maria Buhigas (BCN Ciutat Oberta) • Carles Julbe (ERC) • Marta Alonso (ERC) • Mercè Amat (ERC) • Oriol Illa (ERC) • Xavier Garriga (ERC) • Jordi Angusto (MES) • Ana Isabel Alcocer (CAT SÍ) • Robert Masih (ERC) • Anna Casas (ERC) • Maria Josep López (ERC) • Guillem Casals (ERC) • Sandra Rodríguez (Catalunya Sí) • Albert Delgado (ERC) • Maria Àngels Oró (MES) • Josep Maria Martí (ERC) • Alba Metge (ERC) • Laia Nebot (ERC) • Carles Manjón (MES) • Mireia Sabaté (ERC) • Jordi Balsells (ERC) • Maria Dolors Escriche (ERC) • Carlos Rodríguez (ERC) • Daniel Gómez (ERC) • Pau de Solà-Morales (BCN Ciutat Oberta) • Isaura Gonzàlez (ERC) • Antoni Serrano (ERC) • Olga Hiraldo (ERC) • Núria Pi (ERC) • Santiago Lapeira (AVANCEM) • Ernest Maragall (MES) • Santiago Vidal (Catalunya Sí) Suplents: S.1. Josep González-Cambray (ERC) S.2. Ramon Fort (ERC) S.3. Marc Alegre (ERC) S.4. Judit Pellicer (ERC) S.5. Gemma Domínguez (ERC) S.6. Eduard Cuscó (ERC) S.7. Joan Rial (ERC) S.8. Joaquim Asensio (ERC) S.9. Dolors Martínez (ERC) S.10. Montserrat Bartomeus (ERC) 1. ALFRED BOSCH 54 anys. Escriptor, historiador i diputat d’ERC al Congrés espanyol. 2. JUANJO PUIGCORBÉ 59 anys. Actor de cinema, teatre i televisió. Ha participat en més d’un centenar de projectes com a actor i també com a director de teatre. Acumula més d’una desena de guardons. -

Aires Nous a ERC?

Aires nous a ERC? A fi d’acarar amb un mínim de garanties les eleccions espanyoles, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya sembla voler recobrar aquell “aire nou” impulsat per “mans netes” que tants bons resultats li va donar en el seu moment. No tan sols ha canviat el seu president, substituint Joan Puigcercós per Oriol Junqueras, sinó que —després d’una més que lamentable lluita intestina fratricida— ha tingut la bona idea d’escollir un independent amb empenta, Alfred Bosch, com a cap de llista per la demarcació de Barcelona. Convidant, a més a més, a les altres forces independentistes a afegir-se al seu projecte. Crida que desoí Solidaritat Catalana, però que acollí amb els braços esbatanats Reagrupament, aquella fracassada formació política on s’havien reunit les seves ovelles negres esgarriades. Talment com si, després de la seva espectacular esfondrada electoral, Joan Carretero i els seus n’haguessin tingut prou amb un estentori i temptador xiulet del seu vell pastor per a retornar, amb la cua entre cames, a la cleda que fins fa tot just quatre dies tant els engavanyava. Fa la impressió que per a dedicar-se a la política sigui necessari comptar amb un cert component de desmemòria adaptativa, que permeti patir sobtats atacs d’amnèsia quan més convé. Ataca d’amnèsia que, si és possible, s’haurien d’encomanar als electors... Hem de recórrer a les hemeroteques a fi de recordar que, encara no fa un any i mig, el llavors Conseller d'Innovació, Universitats i Empresa, Josep Huguet, definia al líder de Reagrupament com un independentista “de dreta” —“digues-li dreta, digues-li populista”? O que l’incombustible Puigcercós, que segueix aferrat contumaçment a l’executiva nacional d’ERC, el convidava a abandonar Esquerra per a “omplir l’espai de centredreta independentista”. -

EL PROCÉS SOBIRANISTA I L'esquerra INDEPENDENTISTA Publicació D’EndavantOSAN: La Barraqueta C

ENDAVANT OSAN endavant.org EL PROCÉS SOBIRANISTA I L'ESQUERRA INDEPENDENTISTA PublicaciÓ d’EndavantOSAN: La Barraqueta C. Tordera, 30 (08012 Barcelona) RacÓ de la Corbella C. Maldonado, 46 (46001 ValÈncia) Ateneu Popular de Palma C. MissiÓ, 19 (07011 Palma) Contacte: [email protected] 1 EL PROCÉS SOBIRANISTA I L'ESQUERRA INDEPENDENTISTA El procÉs sobiranista i l'esquerra independentista Els objectius fonamentals de l'esquerra independentista 3 D'on ve l'actual procÉs sobiranista? 4 Quines sÓn les caracterÍstiques de l'independentisme majoritari avui en dia? 7 El paper de les elits econÒmiques 9 Perspectives de canvi social 12 El procÉs sobiranista i els PaÏsos Catalans 14 Objectius, etapes i lÍnies d'actuaciÓ en els propers mesos 17 endavant.org 2 Els objectius fonamentals de l'esquerra independentista L'objectiu final de l'esquerra independentista És la independÈncia, el socialisme i el feminisme als PaÏsos Catalans. És a dir, la constituciÓ d'un estat independent que englobi el conjunt de la naciÓ catalana i la construcciÓ d'una societat socialista i fe minista. Qualsevol actuaciÓ polÍtica, des de la intervenciÓ en una lluita conjuntural fins a les estratÈgies polÍtiques nacionals o territorials, ha d'anar encaminada a l'acumulaciÓ de forces per a poder assolir aquest objectiu final que És la raÓ de ser del nostre moviment. Per tant, la mobilitzaciÓ independentista que actualment viu el Principat de Catalu nya, tambÉ cal que la inserim en aquesta mateixa lÒgica d'analitzarla i intervenirhi polÍticament amb l'objectiu d'acumular forces i avanÇar cap a la consecuciÓ del nos tre projecte polÍtic. -

Torra Encarrega a Bosch Actuar Com a «Ministre D'afers Exteriors» Català

Política | | Actualitzat el 23/11/2018 a les 09:15 Torra encarrega a Bosch actuar com a «ministre d'Afers Exteriors» català El nou conseller promet el càrrec i el president li encomana que Catalunya sigui "coneguda i reconeguda" Quim Torra i Alfred Bosch, en el moment de la presa de possessió | ND Alfred Bosch ja és, oficialment, conseller d'Acció Exterior, Relacions Institucionals i Transparència. Ha pres possessió del càrrec al Saló Sant Jordi del Palau de la Generalitat i, després, ha fet efectiu el traspàs de carteres amb el seu antecessor en el càrrec, Ernest Maragall. Es tracta del primer relleu en el Govern de Quim Torra, que ha presidit l'acte i l'ha tancat amb un breu discurs en el qual ha demanat a Bosch que actuï com a "ministre d'Afers Exteriors" per tal que Catalunya sigui "coneguda i reconeguda", així com també el seu dret a l'autodeterminació. "Toca explicar l'amenaça als drets civils", ha assenyalat el president de la Generalitat. Torra ha agraït la feina de Maragall, basada en la reobertura de les delegacions exteriors i del Diplocat. "La restitució era imprescindible per avançar cap a la República", ha apuntat el president, que ha desitjat sort en la cursa electoral a Barcelona. Cal "explicar Catalunya al món", que sigui "coneguda i reconeguda". Ha recordat un llibre de Bosch sobre Nelson Mandela, de qui en va destacar la capacitat de negociar sense renunciar a "allò que és just". "Us demano que actueu com a ministre d'Afers Exteriors del país, amb la mirada posada en els objectius. -

Acts of Dissent Against 'Mass Tourism' in Barcelona[Version 1; Peer

Open Research Europe Open Research Europe 2021, 1:66 Last updated: 30 SEP 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE A summer of phobias: media discourses on ‘radical’ acts of dissent against ‘mass tourism’ in Barcelona [version 1; peer review: 2 approved, 1 approved with reservations] Alexander Araya López Department of Linguistics and Comparative Cultural Studies, Ca' Foscari University of Venice, Venezia, Venezia, 30123, Italy v1 First published: 10 Jun 2021, 1:66 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.13253.1 Latest published: 10 Jun 2021, 1:66 https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.13253.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract In the summer of 2017, the young group Arran coordinated a series of 1 2 3 protests in Barcelona and other Spanish cities to denounce the negative effects of global mass tourism. These acts of dissent fueled a version 1 heated public debate in both Spanish and international press, mainly 10 Jun 2021 report report report due to the ‘radical’ tactics employed by the demonstrators. Following the narratives about these protest acts across a diversity of media 1. Freya Higgins-Desbiolles , University of outlets, this article identifies the complex power struggles between the different actors involved in the discussion on the benefits and South Australia, Adelaide, Australia externalities of global mass tourism, offering an extensive analysis of the political uses of the term ‘turismofobia’ (tourismphobia) and a 2. Neil Hughes , University of Nottingham, revisited interpretation of the notion of the ‘protest paradigm’. This Nottingham, UK qualitative analysis was based on more than 700 media texts (including news articles, op eds and editorials) collected through the 3. -

The Catalan Struggle for Independence

THE CATALAN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE An analysis of the popular support for Catalonia’s secession from Spain Master Thesis Political Science Specialization: International Relations Date: 24.06.2019 Name: Miquel Caruezo (s1006330) Email: [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. Angela Wigger Image Source: Photo by NOTAVANDAL on Unsplash (Free for commercial or non-commercial use) Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ......................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Resource Mobilization Theory ...................................................................................................... 7 1.1.1 Causal Mechanisms ................................................................................................................ 9 1.1.2 Hypotheses........................................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Norm Life Cycle Theory ............................................................................................................... 11 1.2.1 Causal Mechanisms ............................................................................................................. -

An Ever More Divided Union?

An ever more divided Union? Contemporary separatism in the European Union: a comparative case study of Scotland, Catalonia and Flanders MA Thesis by T.M. Wencker (s1386042) European Union Studies, Leiden University [email protected] Supervisor: Prof. Dr. J.Q.T. Rood Second Marker: Dr. Mr. Anne-Isabelle Richard 2 1 Figure A: 'If all separatists had their way... 1 One Europe, If all separatists had their way…, (25-07-2013) accessed at 07-09-2014 via: http://one- europe.info/in-brief/if-all-separatists-had-their-way 3 Table of contents: - Introduction p.6 o Note on sources and methods p.9 o Note on Scottish case p.9 - Part I: An analysis of European separatism o Chapter I: Separatism as a phenomenon . Definitions p.11 . Origins p.12 . Self-determination p.14 . Unilateral Secession p.15 . Chapter review and conclusions p.18 - Part II: The cases of Scotland, Catalonia and Flanders o Chapter II: Scotland . Background p.21 . The case for Scottish independence p.23 . The imagined community of Scotland p.25 . It’s Scotland’s oil! P.28 . Scotland and the EU p.31 . EU-membership: a contested bone p.34 . Chapter review and conclusions p.37 o Chapter III: Catalonia . Background p.39 . The imagined community of Catalonia p.42 . The case for Catalonian independence p.47 . Unilateral secession and the EU? P.50 . Chapter review and conclusions p.54 o Chapter IV: Flanders . Background p.55 . The Belgian imagined communities p.56 . Understanding Flemish separatism p.59 . Flanders and the EU p.61 . Chapter review and conclusions p.62 - Part III: Connecting the dots: conclusions about separatism in the European Union o Chapter V: connecting the dots . -

Bulls and Donkeys. National Identity and Symbols in Catalonia and Spain

9TH ANNUAL JOAN GILI MEMORIAL LECTURE Miquel Strubell i Trueta Bulls and donkeys. National identity and symbols in Catalonia and Spain The Anglo-Catalan Society 2008 2 Bulls and donkeys. National identity and symbols in Catalonia and Spain 9TH ANNUAL JOAN GILI MEMORIAL LECTURE Miquel Strubell i Trueta Bulls and donkeys. National identity and symbols in Catalonia and Spain The Anglo-Catalan Society 2008 2 3 The Annual Joan Gili Memorial Lecture Bulls and donkeys. National identity and symbols in Catalonia and 1 Spain In this paper, after an initial discussion about what identity means and how to measure it, I intend to review some studies and events in Spain in which identity issues arise. The conclusion will be reached that identities in Spain, in regard to people’s relationship with Spain itself and with Catalonia, are by no means shared, and the level of both stereotyping and prejudice, on the one hand, and of collective insecurity (even “self-hatred”) on the other, are, I claim, higher than in consolidated nation-states of western Europe, with the partial exceptions of the United Kingdom and Belgium. Let me from the outset say how honoured I am, in having been invited to deliver this paper, to follow in the footsteps of such outstanding Catalan academics as Mercè Ibarz, Antoni Segura, Joan F. Mira, Marta Pessarrodona, Miquel Berga … and those before them. The idea of dedicating what up till then had been the Fundació Congrés de Cultura lectures to the memory of Joan Gili (Barcelona 1907 - Oxford 1998) was an inspiration. Unlike some earlier Memorial lecturers, however, I was fortunate enough to have a special personal relationship with him and, of course, with his wife Elizabeth. -

The Regions of Spain

© 2017 American University Model United Nations Conference All rights reserved. No part of this background guide may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means whatsoever without express written permission from the American University Model United Nations Conference Secretariat. Please direct all questions to [email protected] A NOTE Julia Clark Chair Estimats Diputats del Parlament de Catalunya, Dear Diputats of the Parliament of Catalonia, My name is Julia Clark and I’ll be serving as your Chair for the Parliament of Catalonia. I cannot wait to meet all of you in February. Time is of the essence and the Catalan Republic needs creating! As for a little bit about myself: MUN is my life! Last year, I served on the AmeriMUNC Secretariat as the Charges D’Affaires and currently I am an Assistant Head Delegate of the AU Model United Nations competitive travel team. I have done MUN for seven years, competing at 24 conferences across the US and Canada, and I once chaired a conference in the Netherlands! I’m proud to say that AmeriMUNC will be my eighth time chairing. Outside of MUN, I am also the President of my sorority, Phi Mu. If you have any questions about greek life or collegiate MUN, I’d love to chat via email or at the conference. I’m personally very excited to be forming our own new nation, the Catalan Republic. I just studied abroad for four months in Madrid, Spain and was at the center of the real life action surrounding the Catalan independence movement. -

Europa L’Entrevista Ja Som a L’Estiu I Moltes De De La Nostra Voluntat

La Veu Butlletí de Reagrupament Independentista Europa L’entrevista Ja som a l’estiu i moltes de de la nostra voluntat. Europa les esperances de la primavera ens espera com un estat més i Dr. Moisès Broggi: ja no les tenim... només depèn de nosaltres de Una esperança: que el voler-ne ser protagonistes. “Cada vegada hi ha Parlament Europeu fos El company Jordi Gomis ho menys arguments competent per regular el tenia molt clar, i com ell va dret de ciutadania de la UE; deixar escrit: «És una obvietat per continuar sent una altra: que la situació que si Catalunya fos un Estat, part d’un estat que econòmica no ens endinsés no tindríem espoli fiscal, i en un pou de la mà de la per tant, els recursos dels que ens ofega” incompetència espanyola. disposem es multiplicarien PÀGINA 4 La Comissió Europea ens automàticament. Més enllà de ha dit que el Parlament no desempallegar-nos d’un Estat és competent per regular que xucla els nostres recursos Recordem Jordi Gomis sobre la ciutadania europea, i ens ofega econòmicament, Un altre Franco però ens ha indicat dos fets les dades també demostren molt importants: admet la que els estats petits de la UE Dèficits i balances possibilitat de secessió d’una han crescut molt per sobre fiscals part d’un Estat membre i que els grans, prenent les considera la solució en la dades que van des del 1979 /&(- negociació dins l’ordenament fins els nostres dies... En jurídic internacional. definitiva, tenim dues opcions: D’aquesta forma la Comissió esperar que després de 23 Resultats de 30 anys Europea desmenteix les anys