Parochial Vicarages in Lincgln Diocese During the Thirteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholics and Jews: and for the Sentiments Expressed

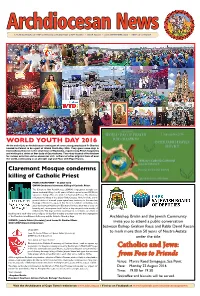

Archdiocesan News A PUBLICATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH OF CAPE TOWN • ISSUE NO 81 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2016 • FREE OF CHARGE WORLD YOUTH DAY 2016 At the end of July an Archdiocesan contingent of seven young people (and Fr Charles) headed to Poland to be a part of World Youth Day 2016. They spent some days in Czestochowa Diocese in the small town of Radonsko, experiencing Polish hospitality and visiting the shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa. Then they headed off to Krakow for various activities and an encounter with millions of other pilgrims from all over the world, culminating in an all-night vigil and Mass with Pope Francis. Claremont Mosque condemns killing of Catholic Priest PRESS STATEMENT – 26 JULY 2016 CMRM Condemns Inhumane Killing of Catholic Priest The Claremont Main Road Mosque (CMRM) congregation strongly con- demns the brutal killing of an 85 year-old Catholic priest by two ISIS/Da`ish supporters during a Mass at a Church in Normandy, France. The inhumane and gruesome killing of the elderly Father Jacques Hamel and the sacrili- geous violation of a sacred prayer space bears testimony to the merciless ideology of Da`ish. It is apparent that Da`ish is hell-bent on fuelling a reli- gious war between Muslims and Christians. However, their war is a war on humanity and our response should reflect a deep respect for the sanctity of all human life. This tragic incident should spur us to redouble our efforts at reaching out to each other across religious divides. Our thoughts and prayers are with the congregation of the Church in Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray and the Catholic Church at large. -

Empingham Village Walk 23 September 2006 (Updated 2020)

Thomas Blore in The History and Antiquities of the Rutland Local History & County of Rutland (Vol. 1, Pt. 2, 1811) notes that there was a chapel of St. Botolph in what is now Chapel Spinney on Record Society Chapel Hill to the east of the village. The location is Registered Charity No. 700273 marked on some old maps. Empingham Village Walk 23 September 2006 (updated 2020) Copyright © Rutland Local History and Record Society All rights reserved INTRODUCTION Chapel of St Botolph on John Speed's map of c1610 Empingham lies in the Gwash Valley, near the eastern end of Rutland Water. When the reservoir was under Earthworks in Hall Close, to the south-west of the construction in the early 1970s archaeological excavations village, ([20] on the walk map, but not part of this walk) confirmed that this area had been occupied for many mark the moated site of a manor house, probably the hall centuries. Discoveries included: which Ralph de Normanville was building in 1221. It is • Traces of an Iron Age settlement recorded that the king, Henry III, gave instructions for • Two Romano-British farming settlements Ralph to take six oak trees from the forest to make crucks • Pagan and Christian Anglo-Saxon cemeteries for this project (Victoria County History, A History of the The most enduring legacy the Saxons left to County of Rutland, Volume 2, 1935) Empingham was its name. The ending ‘ingham’ denotes one of the earlier settlements, older than those with ‘ham’ and ‘ton’ endings. So Empingham was the home of the ‘ing’ or clan of Empa. -

XIX.—Reginald, Bishop of Bath (Hjjfugi); His Episcopate, and His Share in the Building of the Church of Wells. by the Rev. C. M

XIX.—Reginald, bishop of Bath (HJJfUgi); his episcopate, and his share in the building of the church of Wells. By the Rev. C. M. CHURCH, M.A., F.8.A., Sub-dean and Canon Residentiary of Wells. Read June 10, 1886. I VENTURE to think that bishop Eeginald Fitzjocelin deserves a place of higher honour in the history of the diocese, and of the fabric of the church of Wells, than has hitherto been accorded to him. His memory has been obscured by the traditionary fame of bishop Robert as the "author," and of bishop Jocelin as the "finisher," of the church of Wells; and the importance of his episcopate as a connecting link in the work of these two master-builders has been comparatively overlooked. The only authorities followed for the history of his episcopate have been the work of the Canon of Wells, printed by Wharton, in his Anglia Sacra, 1691, and bishop Godwin, in his Catalogue of the Bishops of England, 1601—1616. But Wharton, in his notes to the text of his author, comments on the scanty notice of bishop Reginald ;a and Archer, our local chronicler, complains of the unworthy treatment bishop Reginald had received from Godwin, also a canon of his own cathedral church.b a Reginaldi gesta historicus noster brevius quam pro viri dignitate enarravit. Wharton, Anglia Sacra, i. 871. b Historicus noster et post eum Godwinus nimis breviter gesta Reginaldi perstringunt quae pro egregii viri dignitate narrationem magis applicatam de Canonicis istis Wellensibus merita sunt. Archer, Ghronicon Wellense, sive annales Ecclesiae Cathedralis Wellensis, p. -

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

10751 WLDC Saxilby.Fh11

ROUND AND ABOUT West Lindsey District SAXILBY STREET MAP SAXILBY with INGLEBY ...the highpoint of Lincolnshire Bransby Home of Rest for Horses WHERE TO EAT The Bransby Home cares for AD IN SAXILBY RO over 250 rescued horses, H RC U ponies and donkeys. In CH The Bridge Inn addition, the Bransby Home Tel: 01522 702266 has over 140 animals which www.thebridgeinnsaxilby.co.uk are placed with private MANOR ROAD Inset L/R St. Botolph Church | Saxilby Post Office / High Street families. Open to visitors Harbour City Chinese Restaurant Sun Inn Public House every day of the year from Burton Waters Marina MILL LANE 8am to 4pm. Tel: 01522 575031 Tel: 01427 788464 www.harbourcitylincs.co.uk Village HIGHFIELD ROAD iable for any inaccuracy contained herein. Hall H www.bransbyhorses.co.uk SY Lemon Tree Café KE IG S L H ANE S Living Gardens, T School HISTORY R Saxilby Riding School EE Skellingthorpe Road, T Children can learn more about Recreation Tel: 01522 702405 Ground horses and how to care for Saxilby Station them. Expert tuition is Madarin Chinese Takeaway BRI DGE STREET provided for the children by Tel: 01522 702888 ANK ST B Turn left down Church Lane and you will see the Church of St Retrace your steps to the centre of the village. Passing St. Andrew’s Turn right into West Bank, pass over the level crossing and qualified staff, both in the WE indoor and the outdoor school. Pyewipe Inn A57 Botolph on your right. The church is open all day, and a visit is highly Mission Church at the corner of Station Approach on the right. -

John Spence Pembroke College, Cambridge

The Identity of Rauf de Boun, Author of the Petit Bruit John Spence Pembroke College, Cambridge The chronicle called the Petit Bruit was written by meistre Rauf de Boun in 1309. 1 The Petit Bruit is preserved in full in only one manuscript: London, British Library, MS Harley 902, ff. I' - II '.' It recounts the history of England from the arrival oflegendary Trojan founder Brutus down to Edward I, interspersed with legendary characters such as King Arthur, Havelok and Guy of Warwick. This might sound like a familiar pattern for a late medieval chronicle of England, but despite this the identity of the Petit Bruit's sources have remained unclear.' Many details of Rauf de Boun's account differ greatly from the legendary history familiar from Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae and its descendants, and the Petit Bruit sometimes also distorts more factual material, as when Edward the Confessor is succeeded by his brother, the imaginary Miles, who in turn is murdered by Harold, who has also become Edward the Confessor's (and Miles's) brother.' It has to be said that Raurs grasp of the span of English history does not seem very firm, and he has been much criticised for this, most memorably by Sir Frederic Madden who ;n 1828 referred to him as a 'miserable History-monger'.' The anomalous nature of the Petit Bruit has perhaps led historians to undervalue the work, however. After all, playing fast and loose with Geoffrey of Monmouth's confection of British legends hardly disqualifies Rauf de Boun from being a capable chronicler of more recent history. -

King John and Rouen: Royal Itineration, Kingship, and the Norman ‘Capital’, C

Cardiff Historical Papers King John and Rouen: Royal itineration, kingship, and the Norman ‘capital’, c. 1199 c. 1204 Paul Webster 2008/3 Cardiff Historical Papers King John and Rouen: Royal itineration, kingship, and the Norman ‘capital’, c. 1199 c. 1204 Paul Webster 2008/3 Cardiff Historical Papers Published by the Cardiff School of History and Archaeology, Cardiff University, Humanities Building, Colum Road, Cardiff CF10 3EU, UK General Editor: Dr Jessica Horsley Cardiff Editorial Advisory Board Prof. Gregor Benton Dr Guy Bradley Dr Helen Nicholson Dr Kevin Passmore External Editorial Advisory Board Prof. Norman Housley (University of Leicester) Prof. Roger Middleton (University of Bristol) Prof. Geoffrey Swain (University of Glasgow) Prof. Hans van Wees (University College London) Prof. Andy Wood (University of East Anglia) ISSN 1754‐2472 (Print) ISSN 1754‐2480 (Online) Text copyright: the author Cover: detail from a plan of Cardiff by John Speed, dated 1610, used by kind permission of Glamorgan Record Office, Ref. 2008/1273 Cover design and production: Mr John Morgan All titles in the series are obtainable from Mr John Morgan at the above address or via email: [email protected] These publications are issued simultaneously in an electronic version at http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/hisar/research/projectreports/historicalpapers/index.html King John and Rouen: Royal itineration, kingship, and the Norman ‘capital’, c. 1199–c. 12041 On Sunday 25 April 1199, before he became king of England, John was acclaimed Duke of Normandy in Rouen Cathedral and invested with a coronet of golden roses.2 The Life of St Hugh of Lincoln, written with the considerable benefit of hindsight later in the reign, claimed that John was ‘little absorbed by the rite’, adding that he carelessly dropped the ducal lance placed ‘reverently in his hand’ by the archbishop of Rouen, Walter of Coutances. -

David Hugh Farmer . an Appreciation

David Hugh Farmer . An Appreciation Anne E. Curry University of Reading On 29 June 1988, over 80 past and present members and supporters of the Graduate Centre for Medieval Studies gathered for its annual summer sy mposium, on this occasion dedicated to the theme of 'Saints' to mark the retirement of David Hugh Farmer. It may seem odd to begin an appreciation of David with a remembrance of the end of his time at Reading, but that June day (by happy coincidence the double feast of Saints Peter and Paul) very much summed up David's important contribution to Medieval Studies in this University. The large audience present testified to the affection and respect in which he was, and is, held by the many staff and students who have known him. Several unable to attend sent their greetings. The theme of 'Saints', which David has made very much hi s own, with such memorable consequences, proved as stimulating as it was appropriate to the occasion. The 1988 summer symposium was one of the most successful, enjoyable and uplifting meetings that the GCMS has ever staged. The spirit of good humour, combined with academic stimulation, permeated the assembly and David himself spoke with his customary sensitivity and commitment. It seemed only natural to publish a volume of essays on 'Saints' based on the proceedings of June 1988 (the papers by Drs Kemp and Millett), and we are extremely pleased that others who knew David eilher as fellow academics, in the case of Professors Holdsworth and Morris, or research students, in the case of Margaret Harris and Nigel Berry, have been able to add their contributions. -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-78218-0 - The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Volume II 1100-1400 Edited by Nigel Morgan and Rodney M. Thomson Index More information General index A Description of England 371 A¨eliz de Cund´e 372 A talking of the love of God 365 Aelred of Rievaulx xviii, 6, 206, 322n17, 341, Abbey of the Holy Ghost 365 403n32 Abbo of Saint-Germain 199 Agnes (wife of Reginald, illuminator of Abel, parchmenter 184 Oxford) 178 Aberconwy (Wales) 393 Agnes La Luminore 178 Aberdeen 256 agrimensores 378, 448 University 42 Alan (stationer of Oxford) 177 Abingdon (Berks.), Benedictine abbey 111, Alan de Chirden 180–1 143, 200, 377, 427 Alan of Lille, Anticlaudianus 236 abbot of, see Faricius Proverbs 235 Chronicle 181, 414 Alan Strayler (illuminator) 166, 410 and n65 Accedence 33–4 Albion 403 Accursius 260 Albucasis 449 Achard of St Victor 205 Alcabitius 449 Adalbert Ranconis 229 ‘Alchandreus’, works on astronomy 47 Adam Bradfot 176 alchemy 86–8, 472 Adam de Brus 440 Alcuin 198, 206 Adam of Buckfield 62, 224, 453–4 Aldhelm 205 Adam Easton, Cardinal 208, 329 Aldreda of Acle 189 Adam Fraunceys (mayor of London) 437 Alexander, Romance of 380 Adam Marsh OFM 225 Alexander III, Pope 255, 372 Adam of Orleton (bishop of Hereford) 387 Alexander Barclay, Ship of Fools 19 Adam de Ros, Visio S. Pauli 128n104, 370 Alexander Nequam (abbot of Cirencester) 6, Adam Scot 180 34–5, 128n106, 220, 234, 238, 246, Adam of Usk 408 451–2 Adelard of Bath 163, 164n137, 447–8, De naturis rerum 246 450–2 De nominibus utensilium 33, 78–9 Naturales -

9 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

9 bus time schedule & line map 9 Oakham - Stamford View In Website Mode The 9 bus line (Oakham - Stamford) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Oakham: 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM (2) Stamford: 7:53 AM - 3:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 9 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 9 bus arriving. Direction: Oakham 9 bus Time Schedule 22 stops Oakham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM Bus Station, Stamford 12 All Saints Street, Stamford Tuesday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM All Saints' Church, Stamford Wednesday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM 12 All Saints Place, Stamford Thursday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM Beverley Gardens, Stamford Friday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM Casterton Road, Stamford Saturday Not Operational Waverley Gardens, Stamford Caledonian Road, Stamford Ayr Close, Stamford 9 bus Info Casterton Road, Stamford Civil Parish Direction: Oakham Stops: 22 Belvoir Close, Stamford Trip Duration: 27 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Stamford, All Saints' Arran Road (North End), Stamford Church, Stamford, Beverley Gardens, Stamford, Waverley Gardens, Stamford, Caledonian Road, Sidney Farm Lane, Stamford Stamford, Ayr Close, Stamford, Belvoir Close, Stamford, Arran Road (North End), Stamford, Sidney Tolethorpe, Great Casterton Farm Lane, Stamford, Tolethorpe, Great Casterton, Church, Great Casterton, The Plough, Great Church, Great Casterton Casterton, Bus Shelter, Tickencote, School Lane, Empingham, Wiloughby Drive, Empingham, Exton The Plough, Great Casterton Road, Empingham, Rutland Water -

Information on Historical Epwell

Topology and History of Epwell Village in the 13th century This note attempts to provide some background to the discovery location of the recent Museum acquisition. It in no way implies any tangible connection between the Seal and Epwell. Various sources are used mainly Victoria County History Volume X. A complete gold medieval seal matrix of 13th century date and in exceptional condition. The seal matrix is oval in plan with an applied gold spine and suspension loop on the reverse. In the centre of the front of the matrix is an oval dark green jasper intaglio, intricately engraved to depict a female in profile. The female wears a long veil about her head with either hair, or possibly pearls, visible above the forehead. The matrix has a personal legend in Latin around the outer edge beginning with a six-pointed star and reads '*SIGILVM : SECRETI : hEN :', translated as the 'Secret sea… Topology As the crow flies, Epwell is situated half-way between the towns of Banbury and Shipston-on-Stour, on the Oxfordshire-Warwickshire boundary. Its companion villages are Swalcliffe, Sibfords Gower and Feris, Tadmarton, Shutford and Shennington. Its nearest town is Banbury, 6.5 miles away, but Epwell was always the most remote of its villages, in some periods over 4 hours by cart from Banbury. The village of 1140 acres lies 180 m. (600 ft.) above sea level with a sheltering ring of low hills reaching up to 220 m. (743 ft). The land is of a sandy brown, oolitic limestone which has formed layers of clay at the foots of the slopes. -

The Heritage of Rutland Water

Extra.Extra pages 7/10/07 15:28 Page 1 Chapter 30 Extra, Extra, Read all about it! Sheila Sleath and Robert Ovens The area in and around the Gwash Valley is not short of stories and curiosities which make interesting reading. This chapter brings together a representative sample of notable personalities, place names, extraordinary events, both natural and supernatural, and tragedies including murder most foul! The selected items cover a period of eight hundred years and are supported by extracts and images from antiquarian sources, documentary records, contemporary reports and memorials. A Meeting Place for Witches? The name Witchley originates from the East and West Witchley Hundreds which, in 1086, were part of north Northamptonshire. However, following a boundary change a few years later, they became East Hundred and Wrangdike Hundred in the south-east part of Rutland. Witchley Heath, land lying within an area approximately bounded by Normanton, Empingham and Ketton, was named as a result of this historical association. It is shown on Morden’s 1684 map and other seventeenth and eighteenth century maps of Rutland. Witches Heath, a cor- ruption of Witchley Heath, is shown on Kitchin and Jeffery’s map of 1751. The area of heathland adjacent to the villages of Normanton, Ketton and Empingham became known locally as Normanton Heath, Ketton Heath and Empingham Heath. By the nine- teenth century the whole area was Kitchin and better known as Empingham Heath. The name Witchley was, however, Jeffery’s map of retained in Witchley Warren, a small area to the south-east of Normanton 1751 showing Park, and shown on Smith’s map of 1801.