1 Catholic Schools in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Light Signals Quest for Auxiliary

Lord, Let Glasgow Flourish by the preaching of Thy Word and the praising of Thy Name JULY 2015 JOURNAL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF GLASGOW 70p Joie de vivre! A SPIRIT of joy filled St Andrew’s Cathedral as children and young people with additional support needs joined Archbishop Philip Tartaglia for Mass. The theme ‘Rejoice’ reflected the Gospel passage of Mary’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth – whose child in her womb leapt for joy. The Archbishop spoke of the gifts of life and love and the great joy which the births of John the Baptist and Jesus brought to the world. He encouraged the young people to rejoice and reflect that joy in caring for others and looking after the world. Glasgow Lord Provost Sadie Docherty joined in the celebrations. Picture by Paul McSherry Green light Caritas Glasgow to get signals quest Award another bishop for auxiliary Pope Francis has agreed diocesan bishop’s closest col - with Bishop Joseph Devine the green light to his request, By Vincent Toal laborator, he is expected to be who moved to Motherwell in Archbishop Tartaglia has in - to provide an auxiliary involved in all pastoral proj - 1983. Bishop John Mone then vited people to write to him by bishop for the Arch- an auxiliary following his ects, decisions and diocesan served as auxiliary for four 15 August with preferred pages diocese of Glasgow fol - health scare at the beginning initiatives. years before his appointment names. lowing a request from of the year. With Glasgow embarked on to Paisley in 1988. He will then make a formal 6,7,10,11 Archbishop Philip In an ad clerum letter, sent a wide-ranging review of Although usually chosen submission to the Apostolic out this week, he stated: “I am parish pastoral provision, the from among the diocesan Nuncio who conducts a Tartaglia. -

Bauchi's New Bishop Is 'Home-Made'

DONATE AN SCO SUBSCRIPTION TO A MISSIONARY PRIEST OR SISTER SEE PAGE 9 FOR DETAILS No 5289 Laying down the law on sectarianism Pages Government cracks down on sentencing; police role questioned 3 & 13 No 5417 www.sconews.co.uk Friday May 27 2011 | 90p Bauchi’s new bishop is ‘home-made’ I Cardinal O’Brien installs son of mission’s cook, Malachy John Goltok, to lead Nigerian diocese adopted by Scots By Liz Leydon CARDINAL Keith O’Brien had a very special reason to feel proud at the Episcopal Ordination of Bishop Malachy John Goltok of Bauchi, Nigeria. Cardinal O’Brien traveled to Nigeria to be the principal concelebrating bishop at the Episcopal Ordination last Thursday, to represent both the Holy Father and St Andrews and Edinburgh Archdiocese, which ‘adopted’ Bauchi in the 1950s and sent priests to work there. “It gives me great joy being at this wonderful ordination of the first African bishop of Bauchi to realise I am in a long line of wonderful people forging and strengthening those links which have been of so much benefit both to Africa and to Scotland,” the cardinal said. New bishop Bishop Goltok is the second eldest of a family of ten and his father John was the mission cook in St John’s, Bauchi for more than 20 years, until hi death last year. The newly appointed bishop was parish priest of St Finbarr’s and treasurer of Jos Archdiocese from 2004 before Pope Benedict XVI appointed him as the first Nigerian bishop of Bauchi this February. During the Episcopal ordination, held at the grounds of the Immaculate Conception Secondary School on the outskirts of town, Cardinal O’Brien read the appointment letter from the Vatican and installed the new bishop with a charge for him to lead the Church well and to ensure that justice is done for all. -

Greens Coloured by Anti-Faith Agenda

Concert in honour of Archbishop The call for support by ACN priest for the Emeritus Conti to launch AGAP ART S IN Faithful IN THE CRADLE OF CHRISTIANITY is AUTUMN. New SCO monthly arts section heard by Catholics from the Middle East begins this week. Pages 3, 12-13 and Scotland. Pages 7, 14 No 5486 www.sconews.co.uk Friday September 28 2012 | £1 JOY OF THE RED MASS Cardinal Keith O’Brien pictured alongside Archbishop Philip Tartaglia, Bishop Joseph Toal, Bishop Emeritus Ian Murray, Mgr Peter Magee, Mgr Henry Docherty, Mgr Michael Regan, Lord Gill, Lord Hardie, Lord Drummond and Lord Matthews after Sunday’s Red Mass at St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh I For full story and pics, see page 2 PIC: PAUL McSHERRY Greens coloured by anti-faith agenda I Bishop Joseph Devine accuses political party of taking an anti-religious and anti-democratic stance By Ian Dunn “It would appear that the Green Party has its own graphic images of abortion outside an abortion clinic. officer, said the Green Party here had long been special interpretation of equality that does not extend “All who value freedom of speech and expres- possessed ‘by a radical secularism’ that was hostile BISHOP Joseph Devine of Motherwell has to include any notion of religious freedom,” he said. sion will welcome the dismissal of this case by the to religious freedom and could also be seen in the issued a grave warning about the dangers of the “Prejudice and discrimination against Christians are courts,” the bishop said. “As the two young cam- coverage of the bishop’s comments. -

In Defence of Our Schools

WIN A TRIP TO JOIN THE GRANDPARENTS’ PILGRIMAGE AT KNOCK SEE PAGE 2 No 5289 New national director appointed by MISSIO Pages Fr Tom Welsh speaks about his new role and we look at modern day missions 8, 16 No 5422 www.sconews.co.uk Friday July 1 2011 | 90p In defence of our schools POPE’S DIAMOND JUBILEE I Church criticises Conservative MSP for claiming faith education fuels sectarianism By Martin Dunlop THE Scottish Church this week rallied to defend Catholic educa- tion after a Conservative MSP claimed denominational education fuelled the problem of sectarianism in Scotland. At last Thursday’s Holyrood debate on the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications Bill, John Lamont, the Conservative Party’s CARDINAL O’BRIEN justice spokesman in Scotland, accused the education system in the west of leads the Scottish Scotland of overseeing ‘state-sponsored tributes on the 60th conditioning of sectarian attitudes.’ anniversary of Pope Offensive Benedict XVI’s priestly Bishop Joseph Devine of Motherwell, ordination the president of the Catholic Education Commission, said ‘the claim that Page 9 Catholic schools are the cause of sec- tarianism is offensive and untenable.’ “There has never been any evidence SCOTTISH ORDINATIONS produced by those hostile to Catholicism to support such a malicious misrepresen- tation,” the bishop said. He added that NEW PRIESTS Mr Lamont should ‘either produce the hard evidence to support such irre- Fr Domenico Zanre sponsible claims or withdraw them.’ and Fr Michael Kane The bishop noted that ‘40 million students are taught in Catholic schools ordained for Aberdeen in the UK, Europe, Australia, New and Motherwell Zealand, Canada and the US.’ “If Catholic schools do breed sectari- Page 4 anism, why is there no sectarian prob- lem in all of these other countries around the world?” Bishop Devine said. -

Gay Conspiracy� to Destroy Values Preached by Christianity

T H U R S DAY 13 MARCH 20 0 8 THE SCOTSMAN NEWS 7 Catholic bishop hits out at gay conspiracy to destroy values preached by Christianity ONE of Scotlands most senior TRISTAN STEWART-ROBERTSON Catholics has launched an attack on the “gay lobby” in Scotland, O U T S P O K E N claiming there is a “huge and orchestrated conspiracy taking C H U R C H M A N well-orchestrated conspiracy” place, which the Catholic com- against Christian values. munity missed.” THE Rt Rev Joseph Devine The Rt Rev Joseph Devine, He went on: “In this New Years is no stranger to Bishop of Motherwell and pre- honours list, I saw actor Ian Mc- controversy. sident of the Catholic Education Kellen being honoured for his Last year, he dealt a blow Commission, said gay rights or- work on behalf of homosexuals, to Labour’s hopes in the ganisations aligned themselves when a century ago Oscar Wilde Holyrood elections by saying with minority groups, such as was locked up and put in jail. “Its he would not be voting for Holocaust survivors, to project a very small group of people, but the party on religious an “image of a group of people very active and organised – and grounds, as it had a “morality under persecution”. extremely indulgent. The oppo- devoid of any Christian He warned that the gay lobby sition know exactly what theyre principles”. – which he labelled “the opposi- doing. We dont.” He had previously branded tion” – had mounted “a giant con- Calum Irving, the director of the Labour administration spiracy” to shape public policy. -

Door Opens to God's Mercy For

Looking ahead to Powerful calls to events as the examine voca- Extraordinary Jubilee tions in Glasgow Year of Mercy begins. and beyond. Pages 2, 6-7, 10-11 SUPPORTING 50 YEARS OF SCIAF, 1965-2015 Pages 2, 22 No 5650 VISIT YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER ONLINE AT WWW.SCONEWS.CO.UK Friday December 11 2015 | £1 I As Pope Francis opens the Extraordinary Jubilee Year of Mercy, Scotland prepares to follow his example Door opens to God’s mercy for all By Ian Dunn POPE Francis has said the Church must put mercy first as he opened a Holy Door at St Peter’s Basilica and launched the Extraordinary Jubilee Year of Mercy. The Pope was joined by Pope Emeri- tus Benedict XVI on Tuesday as he pushed open the doors and prayed on the threshold of the Basilica on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. The year, from December 8 to the Feast of Christ the King next November, has been declared a jubilee year during which the faithful can receive blessing and pardon from God and remission of sins. Across the world Holy Doors will be opened in cathedrals and churches with St Andrew’s Cathedral in Glasgow and St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh set to open their Holy Doors on Sunday. vinced of God’s mercy.” Archbishop Leo Cushley of St “But that is the truth,” he went on. Andrews and Edinburgh has said he “We have to put mercy before judge- hopes Catholics will re-embrace the ment, and in any event God’s judgement Sacrament of Confession in the Year will always be in the light of His mercy. -

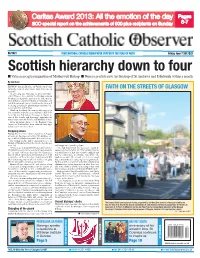

Scottish Hierarchy Down to Four

Caritas Award 2013: All the emotion of the day Pages SCO special report on the achievements of 900 plus recipients on Sunday 6-7 No 5521 YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLICwww.sconews.co.uk NEWSPAPER SUPPORTS THE YEAR OF FAITH Friday June 7 2013 | £1 Scottish hierarchy down to four I Vatican accepts resignation of Motherwell Bishop I Nuncio predicts new Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh within a month By Ian Dunn BISHOP Joseph Devine of Motherwell has FAITH ON THE STREETS OF GLASGOW formally retired, after more than 30 years in the role. At a meeting last Thursday, the priests of Moth- erwell Diocese were told by Archbishop Antonio Mennini, the Apostolic nuncio to the UK, that the Vatican had accepted the bishop’s resignation and that Bishop Joseph Toal of Argyll and the Isles will be acting as Apostolic administrator until the Vat- ican appoints a new bishop. While in Scotland, the nuncio also suggested that a candidate for the vacant bishop’s chair in St Andrews and Edinburgh Archdiocese would be named this month and Episcopal appointments would soon come for Paisley and Dunkeld as well. In the meantime, however, the Bishops’ Con- ference of Scotland has been reduced from eight to four non-retired members. Stepping down Bishop Devine tendered his resignation in August of last year, having reached his 75th birthday, the age at which bishops must offer their retirement. The bishop said he had been proud to serve as Bishop of Motherwell but his time in the role was at an end. and happy’ to be standing down. -

Scotland Braced for a Spiritual Samba

CARNOUSTIE PARISHIONER, 95, Archbishop Emeritus Conti leads his last whom Sir Chris Hoy calls GLAS GOW ARCHDIOCESAN Lourdes ‘Uncle Andy,’ inspires the next pilgrimage. St Aloysius pupils time grotto generation at St Anne’s parish. Page 7 visit to coincide. Pages 22-23 No 5480 www.sconews.co.uk Friday August 17 2012 | £1 POOR CLARES’ RICH HISTORY OF SERVING THE CHURCH Cardinal Keith O’Brien says a few words in the grounds of the Poor Clare Monastery in Bothwell after celebrating a Mass to mark the religious order’s 800th anniversary. For more on the celebrations, see page 5 PIC: PAUL McSHERRY Scotland braced for a spiritual samba I Young Catholics throughout the country prepare to stage their own World Youth Day next summer By Martin Dunlop will be a fantastic event for young Catholics to the football World Cup in the summer of 2014. are part of the universal Church and it is a life-long participate in. Bishop Hugh Gilbert of Aberdeen intends to lead experience for young people. We want to bring a YOUNG Catholics from across the country “For hundreds of thousands of young Catholics a WYD pilgrimage to Brazil from his own diocese bit of that to the young people of Scotland.” have been invited to their own World Youth called together from all over the world by the Holy next summer and some smaller Scottish groups are Ms Riddoch added that she hopes Scotland’s Day in Scotland next summer. Father, World Youth Day is a youthful festival of also expected to attend the event in Rio de Janeiro. -

Historic News on Archives

BISHOP EMERITUS LOGAN leads what is SCIAF reports that Scots saved likely to be his last diocesan pilgrimage thousands of lives after the Horn to Lourdes following his early retirement of Africa drought by making as Bishop of Dunkeld. Pages 22-23 £1 million in donations. Pag e 3 No 5479 www.sconews.co.uk Friday August 10 2012 | £1 WINDOW SNP Marriage bill poses a threat to ON 100TH religious freedom EVENTS AT By Ian Dunn PARISH CARDINAL Keith O’Brien has written to Deputy First Minister Nicola Young St Joseph’s, Helensburgh, Sturgeon warning her that she risks parishioners Hannah Thomson destroying religious liberty in Scotland 10, Amy Gough 13, Connor Press by insisting upon legalising same-sex and Catechist Jenny Gallagher ‘marriage.’ are seen here with Cardinal The cardinal’s letter notes the bishops of Keith O’Brien, Archbishop Scotland are ‘deeply disappointed’ that the Emeritus Mario Conti and parish Scottish Government decided to proceed priest Fr Peter Lennon standing with its plans to re-define marriage two beside the stained glass window weeks ago ‘especially because the govern- designed for the parish ment simply ignored its own consultation.’ centenary. They were joined by That consultation ‘returned a result of Bishop Joseph Devine of two to one against the redefinition of mar- Motherwell, who turned 75 on riage, showing quite emphatically that there Tuesday (see page 3), Scottish was little will for the legalisation of same- clergy and representatives from sex ‘marriage’ among those who responded other churches for the parish’s to the consultation,” the cardinal writes. -

Flourish July 2014

Lord, Let Glasgow Flourish by the preaching of Thy Word and the praising of Thy Name JULY 2014 JOURNAL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF GLASGOW 70p INSIDE Church going out onto street IN response to Pope Francis’ into the lives of all people. call for the Church to go out Archbishop Philip Tartaglia onto the street, Glasgow said: “In the spirit of the new faithful have taken part in the evangelisation, I couldn’t help Corpus Christi procession in thinking that it was also a the city’s West End. loving and respectful Deacon Joe Along streets decked out assurance to the people of with banners welcoming the Glasgow that Jesus offers ordained arrival of the Commonwealth himself as spiritual Games, they carried the nourishment to everyone who page 3 Blessed Sacrament – a wishes to receive from him.” distinct expression of the Picture by Paul McSherry Church’s desire to bring Christ Full story – page 2 Welcome friends! Archbishop Philip Tartaglia greets visitors to Glasgow for Commonwealth Games IF the Commonwealth hosts and the most welcoming of This will explore the vital part Games are known as the human beings. sport can play in proclaiming the Maryhill friendly games then it is only Sport is a gift of God and the dignity and purpose of each per - right that they should come Glasgow Games is an ideal oppor - son, engaging people of all abili - tunity for us to celebrate that gift ties in teamwork and friendly Magyars and to the friendly city of and proclaim the dignity, respect competition, as well as building up Glasgow! and purpose that God bestows on communities with shared goals more nations all people, no matter their ability and ambitions. -

Newmainsbrigid’S

StNEWMAINSBrigid’s 140 1871years 2011 1 PAGE 23 140 YEARS 1871 - 2011 ST BRIGID’S 140 YEARS 1871 - 2011 A Parish consists of the people of God in their community. Ve story of a parish is the story of that community. Vis story deals with the people themselves, working and making sacriRces in their everyday lives, grasping the knowledge that only God’s love can bring meaning to lives which were often brutally hard. Ve story will touch upon the priests who led the people. It will tell of the buildings and other objects which were lovingly constructed by the people and it will describe the civil community in which they lived and earned their living “by the sweat of their brow”. It will, above all, show the continuity of the people. It will show that the impulse to live as God’s people, which drove the founders, remains alive and thriving a century later. Ve wish to celebrate the achievements of our forebears is evidence for that but a stronger indication is the willingness to participate in the life of our community today as we reach the end of the Rrst Chapter of the story of St. Brigid’s. 114400 YYEARSEARS 11871871 - 20112011 PAGEPAGE 1 Right Rev. Joseph Devine Bishop of Motherwell PAGE 2 140 YEARS 11871871 - 20112011 New Letter to follow 140 YEARS 11871871 - 20112011 PAGEPAGE 3 PIC to follow Parish Priest - Rev Hugh Kelly PAGE 4 140 YEARS 11871871 - 20112011 St Brigid’s Church Newmains (Scottish Charities Reg. No. 011041) 5 Westwood Road, Newmains, Wishaw, North Lanarkshire ML2 9DA Tel. -

Comment and Debate on Faith Issues in Scotland August/September 2019 Issue No 283 £2.50 Editorial the Next Steps

Comment and debate on faith issues in Scotland August/September 2019 www.openhousescotland.co.uk Issue No 283 £2.50 Editorial The next steps What next for the conversation on new directions for the ecclesial structures and suggested the need for a new focus Catholic Church in Scotland which began at the Open on process and dialogue. Many people want a regular House conference in June? Reflections from participants on gathering to become part of the ongoing conversation, the lessons they learned (see Letters Special pp 14-17) offer echoing Pope Francis’ call for a synodal church at all levels. some pointers. Participants were inspired by local initiatives (‘nothing at The first is context. We are living at time of transition from all will change unless we individuals make it happen’) and a dying model of church. There are no easy answers to by the way in which people adapted tools to meet local changing an institution with deeply embedded structures of needs. These experiences have already prompted further power. This was reflected by those who felt that the conversations. conversation about new directions has been going on for a Then there is the suggestion that we need to develop a way long time, that clergy are still able to block progress at local of turning the thoughts and ideas generated by the level, and that opposition to Pope Francis’ reforms is deeply conference into practical possibilities for change. The damaging. The importance of leadership was raised by conference organisers and facilitators plan to meet soon to several people. Bishop Leahy was commended for his discuss how this part of the process might be taken forward.