Wired 14.02: Geeks in Toyland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan Brickfest 2018

Japan BrickFest 2018 By Richard Jones Last June I visited Japan BrickFest 2018. The fourth Kobe Fan Weekend took place on Rokko Island, in the port city of Kobe, near Osaka and Kyoto. Organised by Edwin Knight and members of the Kansai LEGO® Users Group (KLUG), this event is a LEGO® hub event for Asia. Exhibitors attended from all over the world – predominantly countries from around Asia, but the USA and Australia were also represented. I arrived on Friday afternoon and set up in one of the two gymnasiums used for the display, accompanied by the majority of builders visiting from overseas. We shared the space with the Great Ball Contraption, a brick built monorail and a train layout. NEXO Classic Space by Richard Jones LEGOLAND Japan had a display, and there was also an area to get your hands on some bricks and just build! The other gymnasium had many exhibitors from around Japan, and a theatre had larger scale models from members of the Kansai LEGO® Users Group. I had taken my NEXO Classic Spaceships. (Imagine the 1978-79 Classic Space sets built with NEXO Knights elements and colours.) This was the third time I had displayed them this year, but the frst time they had travelled more than 1000 km from home. I set about the task of discovering how my models had survived at the hands of international baggage handlers, as well as with myself bouncing between multiple railway stations. I set up my terrain and installed the lighting. Everyone I met was extremely friendly, offering words of encouragement as my various models were unwrapped in more pieces than I remembered them being in when I wrapped them up. -

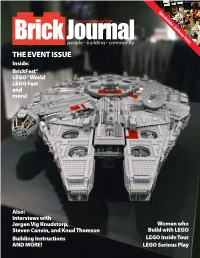

THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: Brickfest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and More!

Epic Builder: Anthony Sava THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: BrickFest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and more! Also: Interviews with Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, Women who Steven Canvin, and Knud Thomson Build with LEGO Building Instructions LEGO Inside Tour AND MORE! LEGO Serious Play Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 4th ® Printing! for Your LEGO Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: Brickfest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and More!

Epic Builder: Anthony Sava THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: BrickFest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and more! Also: Interviews with Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, Women who Steven Canvin, and Knud Thomson Build with LEGO Building Instructions LEGO Inside Tour AND MORE! LEGO Serious Play Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 4th ® Printing! for Your LEGO Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

LEGO® Instructions!

LEGO Publications #50 is a special double- THE MAGAZINE FOR LEGO® size book! ENTHUSIASTS OF ALL AGES! BRICKJOURNAL magazine (edited by JOE MENO) spotlights all aspects of the LEGO® Community, showcasing events, people, and A landmark edition, models every issue, with contributions and celebrating over a how-to articles by top builders worldwide, new decade as the premier product intros, and more. Available in both ® FULL-COLOR print and digital editions. publication for LEGO fans! LEGO®, the Minifigure, and the Brick and Knob configurations (144-page FULL-COLOR paperback) $17.95 are trademarks of the LEGO Group of Companies. BrickJournal is not affiliated with The LEGO Group. ISBN: 9781605490823 • (Digital Edition) $8.99 LEGO® Instructions! YOU CAN BUILD IT is a series of instruction books on the art of LEGO® custom building, from the producers of BRICKJOURNAL magazine! These FULL-COLOR books are loaded with nothing but STEP-BY-STEP INSTRUCTIONS by some of the top custom builders in the LEGO fan community. BOOK ONE is for beginning-to-intermediate builders, with instructions for custom creations including Miniland figures, a fire engine, a tulip, a spacefighter, a street vignette, plus miniscale models from “a galaxy far, far away,” and more! BOOK TWO has even more detailed projects to tackle, including advanced Miniland figures, a mini- scale yellow castle, a deep sea scene, a mini USS Constitution, and more! So if you’re ready to go beyond the standard LEGO sets available in stores and move into custom building with the bricks you already own, this ongoing series will quickly take you from novice to expert builder, teaching you key building techniques along the way! (84-page FULL-COLOR Trade Paperbacks) $9.95 (Digital Editions) $4.99 Customize Minifigures! BrickJournal columnist JARED K. -

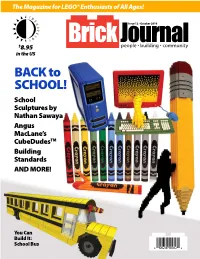

Angus Maclane’S Cubedudestm Building Standards and MORE!

The Magazine for LEGO® Enthusiasts of All Ages! Issue 12 • October 2010 $8.95 in the US BACK to SCHOOL! School Sculptures by Nathan Sawaya Angus MacLane’s CubeDudesTM Building Standards AND MORE! You Can Build It: School Bus 1 82658 00017 2 ® DIGITAL THE MAGAZINE FOR LEGO EDITIONS 6-ISSUE AVAILABLEY ENTHUSIASTS OF ALL AGES! FOR ONL SUBSCRIPTIONS: $3.95 BRICKJOURNAL magazine (edited by Joe Meno) spotlights $57 Postpaid in the US all aspects of the LEGO® Community, showcasing events, ($75 Canada, BRICKJOURNAL #11 BRICKJOURNAL #13 people, and models every issue, with contributions and $86 Elsewhere) “Racers” theme issue, with building tips Special EVENT ISSUE with reports from on race cars by the ARVO BROTHERS, BRICKMAGIC (the newest US LEGO fan how-to articles by top builders worldwide, new product DIGITAL interviews with the LEGO Group on TOP festival, organized by BrickJournal), BRICK- intros, and more. Available in both print ($8.95) and digital SUBSCRIPTIONS: SECRET UPCOMING SETS, photos from WORLD (one of the oldest US LEGO fan $23.70 for six NEW YORK TOY FAIR 2010 and other events), and others! Plus: STEP-BY-STEP form ($3.95). Print subscribers event reports, instructions and columns on INSTRUCTIONS, spotlights on builders and get the digital version FREE! digital issues MINIFIGURE CUSTOMIZATION and minifigure customization, a look at 3-D MICRO BUILDING, builder spotlights, PHOTOGRAPHY with LEGO models, & more! LEGO, the Minifigure, and the Brick and Knob configurations are trademarks of the LEGO Group of Companies. LEGO HISTORY, and -

Automated Brick Sculpture Construction

Automated Brick Sculpture Construction By Eugene Smal A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at Stellenbosch University Supervised by: Dr. Lynette van Zijl December 2008 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: December 2008 Copyright © 2008 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Summary In this thesis we consider the modelling of a particular layout optimisation problem, namely, the LEGO construction problem. The LEGO construction problem, in short, concerns the optimal layout of a set of LEGO bricks to represent a given object. Our goal is to develop a software package which LEGO enthusiasts can use to construct LEGO sculptures for any real-world object. We therefore not only consider the layout optimisation problem, but also the generation of the input data required by the LEGO construction problem. We show that by using 3D geometric models to represent the real-world object, our implemented voxelisation technique delivers accurate input data for the LEGO construction problem. The LEGO construction problem has previously been solved with optimisation tech- niques based on simulated annealing, evolutionary algorithms, and a beam search ap- proach. These techniques all indicate that it is possible to generate LEGO building instructions for real-world objects, albeit not necessarily in reasonable time. We show that the LEGO construction problem can be modelled easily with cellular automata, provided that cells are considered as clusters which can merge or split during each time step of the evolution of the cellular automaton. -

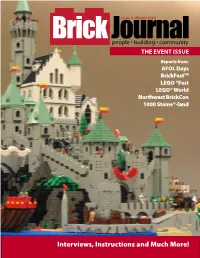

Interviews, Instructions and Much More!

What’s NXT? Brick Journal�������������������� ����������������������������� THE EVENT ISSUE Reports from: AFOL Days BrickFestTM LEGO ®Fest LEGO® World Northwest BrickCon 1000 Steine®-land Interviews, Instructions and Much More! Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 3rd Printing! for Your LEGO® Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

All About the Market Street: Reviews Alternate Builds Modular Building

BrickFest 2007 Report! All About the Market Street: Reviews Alternate Builds Modular Building Models: HMS Edinburgh Pokemon Also: Instructions AND MORE! Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 4th ® Printing! for Your LEGO Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

Returning to Mecha

The Magazine for LEGO® Enthusiasts of All Ages! Issue 48 • November 2017 $8.95 in the US Interviews with Benjamin Cheh, Kelvin Low, Returning Lu Sim, Freddy Tan, to Mecha David Liu and Secrets and Sam Cheng Tricks of LEGO Mecha Building Instructions and MORE! 1 82658 00109 4 Issue 48 • November 2017 Contents From the Editor ..........................................................2 People Mech Builder Spotlight: Benjamin Cheh Ming Hann .............................4 Mech Builder Spotlight: David Liu ..................................................................11 Stand By for Titanfall! ............................................16 Mech Builder Spotlight: Freddy Tan ...............................................................22 Grimlock ......................................................................28 Mech Builder Spotlight: Lu Sim ........................................................................34 Mech Builder Spotlight: Sam Cheng .............................................................38 Noel Encarnacion’s Gundam Papa Bee .....43 Building You Can Build It: Strider Mech ...........................................................48 You Can Build It: MINI Hammerhead Corvette .......................52 If you’re viewing a Digital Edition of this publication, BrickNerd’s DIY Fan Art: PLEASE READ THIS: Guardian ..................................................................56 This is copyrighted material, NOT intended Minifigure Customization 101: for downloading anywhere except our Large Figure Conversion, Part -

Brickjournal - and I Apologize

Finding the Builders of Tomorrow USS Harry S. Truman by Malle Hawking THE ISSUE Big Boys Toys BIG by Mark Stafford Event Reports The Real LEGO Factory BrickStructures AND MORE! by Adam Tucker Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 4th ® Printing! for Your LEGO Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

Moonbots Contest Winners NXT-G Blocks for Hitechnic SMUX Are

Moonbots Contest Winners by Xander 1 person liked this The winners for the Moonbots Contest have been announced! 1. Landroids 2. The Shadowed Craters 3. Moonwalk Congratulations to all teams who took part. All teams got a special recognition award for their efforts, some of which are very funny! Anyway, be sure to check out the teams‘ web sites for more information on what they did and how they did it. Add starLikeShareShare with noteEmailEdit tags: Lego and Robotics Aug 3, 2010 2:23 PM NXT-G Blocks For HiTechnic SMUX Are Here! by Xander 3 people liked this At last, the long anticipated NXT-G blocks for the HiTechnic Sensor MUX have arrived. Gus from HiTechnic has written a nice in-depth article about them on the HiTechnic blog which you can find here: [LINK]. It looks like using them is not a whole lot different from using them without the SMUX. Hurray for transparency. Anyway, hurry on down to the HiTechnic website and start downloading the new blocks right here: [LINK] or here [LINK]. Add starLikeShareShare with noteEmailEdit tags: Lego and Robotics Jul 30, 2010 11:14 AM Hispabrick Magazine 008 is out! by Xander Hispabrick Magazine 008 is out now! The Mindstorms NXT is featured quite a bit in this issue. Some of the highlights: Article about what the Mindstorms Community Partner programme (MCP) is all about; Interviews with some of the people in the MCP programme; A great tutorial on PID and how to apply that to line following; Actuators for the NXT (motors, things that move). -

LEGO MINDSTORMS TUTORIAL ESWEEK [DRAFT: Final PDF Is Uploaded After Module NXT Sunday] 2009 LEGO MINDSTORMS TUTORIAL

LEGO MINDSTORMS TUTORIAL ESWEEK [DRAFT: Final PDF is uploaded after Module NXT Sunday] 2009 http://nxtgcc.sf.net LEGO MINDSTORMS TUTORIAL Outline ESWEEK [DRAFT: Final PDF is uploaded after Sunday] 2009 http://nxtgcc.sf.net Rasmus Ulslev Pedersen [email protected] NXT.1 LEGO MINDSTORMS The presentation overview. TUTORIAL ESWEEK [DRAFT: Final PDF is uploaded after Sunday] 2009 http://nxtgcc.sf.net Overview LEGO c MINDSTORMS c NXT from a community and user standpoint Hardware Description of NXT hardware from a developer perspective Outline Software Description of NXT software with the aim of performing a firmware replacement Note 1: LEGO has sponsored a NXT 2.0 kit, which we will make a draw for at the end of the tutorial. Note 2: LEGOr, MINDSTORMSrare trademarks of LEGOr. The tutorial contains pictures from Atmel ARM7 documentation, and from LEGO documentation. Note 3: There is additional material included: Many slides are supplementary and included for future reference. NXT.2 LEGO MINDSTORMS ESWEEK [DRAFT: Final PDF is uploaded after Sunday] 2009 Module NXT http://nxtgcc.sf.net LEGO MINDSTORMS ESWEEK [DRAFT: Final PDF is uploaded after Sunday] 2009 http://nxtgcc.sf.net Rasmus Ulslev Pedersen [email protected] NXT.1 Outline LEGO MINDSTORMS ESWEEK [DRAFT: Final PDF is uploaded after Sunday] 2009 http://nxtgcc.sf.net NXT.2 Aim LEGO MINDSTORMS ESWEEK [DRAFT: Final PDF is uploaded after Sunday] 2009 http://nxtgcc.sf.net • Includes as USB, SPI, and I2C • How the open source universe around Lego Mindstorms NXT is structured • Talk about a world that