Download the Concert Programme (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8D09d17db6e0f577e57756d021

rus «Как дуб вырастает из желудя, так и вся русская симфоническая музыка повела свое начало из “Камаринской” Глинки», – писал П.И. Чайковский. Основоположник русской национальной композиторской школы Михаил Иванович Глинка с детства любил оркестр и предпочитал сим- фоническую музыку всякой другой (оркестром из крепостных музы- кантов владел дядя будущего композитора, живший неподалеку от его родового имения Новоспасское). Первые пробы пера в оркестро- вой музыке относятся к первой половине 1820-х гг.; уже в них юный композитор уходит от инструментального озвучивания популярных песен и танцев в духе «бальной музыки» того времени, но ориентируясь на образцы высокого классицизма, стремится освоить форму увертюры и симфонии с использованием народно-песенного материала. Эти опыты, многие из которых остались незаконченными, были для Глинки лишь учебными «эскизами», но они сыграли важную роль в формирова- нии его композиторского стиля. 7 rus rus Уже в увертюрах и балетных фрагментах опер «Жизнь за царя» (1836) Александр Сергеевич Даргомыжский был младшим современником и «Руслан и Людмила» (1842) Глинка демонстрирует блестящее вла- и последователем Глинки в деле становления и развития русской про- дение оркестровым письмом. Особенно характерна в этом отноше- фессиональной музыкальной культуры. На репетициях «Жизни за царя» нии увертюра к «Руслану»: поистине моцартовская динамичность, он познакомился с автором оперы; сам Глинка, отметив выдающиеся «солнечный» жизнерадостный тонус (по словам автора, она «летит музыкальные способности юноши, передал ему свои тетради музыкаль- на всех парусах») сочетается в ней с интенсивнейшим мотивно- ных упражнений, над которыми работал вместе с немецким теоретиком тематическим развитием. Как и «Восточные танцы» из IV действия, Зигфридом Деном. Даргомыжский известен, прежде всего, как оперный она превратилась в яркий концертный номер. Но к подлинному сим- и вокальный композитор; между тем оркестровое творчество по-своему фоническому творчеству Глинка обратился лишь в последнее десяти- отражает его композиторскую индивидуальность. -

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio's

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia Richard Lee-Thai 30024611 MUSI 333: Late Romantic and Modern Music Dr. Freidemann Sallis Due Date: Friday, April 6th 1 | P a g e Luciano Berio (1925-2003) is an Italian composer whose works have explored serialism, extended vocal and instrumental techniques, electronic compositions, and quotation music. It is this latter aspect of quotation music that forms the focus of this essay. To illustrate how Berio approaches using musical and literary quotations, the third movement of Berio’s Sinfonia will be the central piece analyzed in this essay. However, it is first necessary to discuss notable developments in Berio’s compositional style that led up to the premiere of Sinfonia in 1968. Berio’s earliest explorations into musical quotation come from his studies at the Milan Conservatory which began in 1945. In particular, he composed a Petite Suite for piano in 1947, which demonstrates an active imitation of a range of styles, including Maurice Ravel, Sergei Prokofiev and the neoclassical language of an older generation of Italian composers.1 Berio also came to grips with the serial techniques of the Second Viennese School through studying with Luigi Dallapiccola at the Tanglewood Music Festival in 1952 and analyzing his music.2 The result was an ambivalence towards the restrictive rules of serial orthodoxy. Berio’s approach was to establish a reservoir of pre-compositional resources through pitch-series and then letting his imagination guide his compositional process, whether that means transgressing or observing his pre-compositional resources. This illustrates the importance that Berio’s places on personal creativity and self-expression guiding the creation of music. -

The Russian Five Austin M

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2019 yS mposium Apr 3rd, 1:30 PM - 2:00 PM The Russian Five Austin M. Doub Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Art Practice Commons, Audio Arts and Acoustics Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Doub, Austin M., "The Russian Five" (2019). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 7. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2019/podium_presentations/7 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Austin Doub December 11, 2018 Senior Seminar Dr. Yang Abstract: This paper will explore Russian culture beginning in the mid nineteenth-century as the leading group of composers and musicians known as the Moguchaya Kuchka, or The Russian Five, sought to influence Russian culture and develop a pure school of Russian music. Comprised of César Cui, Aleksandr Borodin, Mily Balakirev, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolay Rimksy-Korsakov, this group of inspired musicians, steeped in Russian society, worked to remove outside cultural influences and create a uniquely Russian sound in their compositions. As their nation became saturated with French and German cultures and other outside musical influences, these musicians composed with the intent of eradicating ideologies outside of Russia. In particular, German music, under the influence of Richard Wagner, Robert Schumann, and Johannes Brahms, reflected the pan-Western-European style and revolutionized the genre of opera. -

Songs of the Mighty Five: a Guide for Teachers and Performers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks SONGS OF THE MIGHTY FIVE: A GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND PERFORMERS BY SARAH STANKIEWICZ DAILEY Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University July, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Ayana Smith, Research Director __________________________________ Mary Ann Hart, Chairperson __________________________________ Marietta Simpson __________________________________ Patricia Stiles ii Copyright © 2013 Sarah Stankiewicz Dailey iii To Nathaniel iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express many thanks and appreciation to the members of my committee—Dr. Ayana Smith, Professor Mary Ann Hart, Professor Marietta Simpson, and Professor Patricia Stiles—for their support, patience, and generous assistance throughout the course of this project. My special appreciation goes to Professor Hart for her instruction and guidance throughout my years of private study and for endowing me with a love of song literature. I will always be grateful to Dr. Estelle Jorgensen for her role as a mentor in my educational development and her constant encouragement in the early years of my doctoral work. Thanks also to my longtime collaborator, Karina Avanesian, for first suggesting the idea for the project and my fellow doctoral students for ideas, advice, and inspiration. I am also extremely indebted to Dr. Craig M. Grayson, who graciously lent me sections of his dissertation before it was publically available. Finally, my deepest gratitude goes to my family for love and support over the years and especially my husband, Nathaniel, who has always believed in me. -

A Tribute to the Mighty Handful the Russian Guitar Quartet

A Tribute to the Mighty Handful The Russian Guitar Quartet DE 3518 1 DELOS DE DELOS DE A Tribute to the Mighty Handful The Russian Guitar Quartet 3518 A TRIBUTE TO THE MIGHTY HANDFUL 3518 A TRIBUTE TO THE MIGHTY HANDFUL 3518 A TRIBUTE TO César Cui: Cherkess Dances ♦ Cossack Dances Modest Mussorgsky: Potpourri from Boris Godunov Mily Balakirev: Mazurka No. 3 ♦ Polka ♦ “Balakireviana” Alexander Borodin: Polovtsian Dances Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade in Spain Total playing time: 64:38 ORIGINAL ORIGINAL DIGITAL DIGITAL A Tribute to the Mighty Handful The Russian Guitar Quartet Dan Caraway, Alexei Stepanov, Vladimir Sumin, Oleg Timofeyev CÉSAR CUI (arr. Oleg Timofeyev): 1. Cherkess Dances (5:53) 2. Cossack Dances (5:24) 3. MODEST MUSSORGSKY (arr. Timofeyev): Potpourri from Boris Godunov (13:25) MILY BALAKIREV (arr. Viktor Sobolenko): 4. Mazurka No. 3 (4:54) 5. Polka (3:17) 6. ALEXANDER BORODIN (arr. Timofeyev): Polovtsian Dances (14:02) MILY BALAKIREV (arr. Alexei Stepanov): “Balakireviana” 7. I – Along the meadow (1:19) 8. II – By my father’s gate (1:49) 9. III – I am tired of those nights (2:54) 10. IV – Under the green apple tree (1:24) 11. NIKOLAY RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (arr. Sobolenko): Scheherazade in Spain (10:12) Total playing time: 64:38 2 NOTES ON THE PROGRAM In a certain way, this album is an attempt to reinvent history. We took the alliance of clas- erious connoisseurs of classical music as sical Russian composers known as “The Mighty well as more superficial listeners usually Handful “ or “The Five” and built a musical trib- Shave a certain image of (if not a prejudice ute to them with our quartet of four Russian about) Russian music. -

2015 Regional Music Scholars Conference Abstracts Friday, March 27 Paper Session 1 1:00-3:05

2015 REGIONAL MUSIC SCHOLARS CONFERENCE A Joint Meeting of the Rocky Mountain Society for Music Theory (RMSMT), Society for Ethnomusicology, Southwest Chapter (SEMSW), and Rocky Mountain Chapter of the American Musicological Society (AMS-RMC) School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, Colorado State University March 27 and 28, 2015 ABSTRACTS FRIDAY, MARCH 27 PAPER SESSION 1 1:00-3:05— NEW APPROACHES TO FORM (RMSMT) Peter M. Mueller (University of Arizona) Connecting the Blocks: Formal Continuity in Stravinsky’s Sérénade en La Phrase structure and cadences did not expire with the suppression of common practice tonality. Joseph Straus points out the increased importance of thematic contrast to delineate sections of the sonata form in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Igor Stravinsky exploited other musical elements (texture, range, counterpoint, dynamics, etc.) to delineate sections in his neoclassical works. While theorists have introduced large-scale formal approaches to Stravinsky’s works (block juxtaposition, stratification, etc.), this paper presents an examination of smaller units to determine how they combine to form coherence within and between blocks. The four movements of the Sérénade present unique variations of phrase construction and continuity between sections. The absence of clear tonic/dominant relationships calls for alternative formal approaches to this piece. Techniques of encirclement, enharmonic ties, and rebarring reveal methods of closure. Staggering of phrases, cadences, and contrapuntal lines aid coherence to formal segments. By reversing the order of phrases in outer sections, Stravinsky provides symmetrical “bookends” to frame an entire movement. Many of these techniques help to identify traditional formal units, such as phrases, periods, and small ternary forms. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Dear Music Lover, Welcome to the 23Rd Year of Music at the National

Dear Music Lover, Welcome to the 23rd year of music at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. We are delighted to have been able to reschedule two of the concerts cancelled last season due to COVID-19 and to have added a third. This season, concerts will begin in the spring of 2021. Our concern for audience and artist safety led us to delay the season with the hope that it will be safer to congregate in person at that time. However we anticipate at this time that the concerts will be virtual. If things do change, we will certainly notify you. Our season kicks off on March 31 with the acclaimed McDermott Trio, featuring Anne-Marie, Kerry, and Maureen McDermott, with master violist Paul Neubauer. The McDermott Trio has been recognized as one of the most exciting trios of their generation and Neubauer has been called "a master musician" by the New York Times due to his exceptional musicality and effortless playing. On May 12, we welcome the talented Stefania Dovhan, who has performed at many opera houses including the Royal Opera House, the New York City Opera, and the Baltimore Lyric Opera. We will close out the season on June 2 with the amazing violinist Jennifer Koh, who is known for her intense, commanding performances delivered with dazzling virtuosity and technical assurance. Since 1998, we have presented more than sixty-nine free concerts featuring emerging and established women musicians who have brought to life the halls of this great museum with their artistry and talent. Thank you for your continued support of the Shenson Chamber Music Concert Series. -

October 17, 2018: (Full-Page Version) Close Window “The Only Love Affair I Have Ever Had Was with Music.” —Maurice Ravel

October 17, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “The only love affair I have ever had was with music.” —Maurice Ravel Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Fernandez/English Chamber 00:01 Buy Now! Vivaldi Lute Concerto in D, RV 93 London 289 455 364 028945536422 Awake! Orchestra/Malcolm 00:13 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 059 in A, "Fire" English Concert/Pinnock Archiv 427 661 028942766129 00:32 Buy Now! Fauré Violin Sonata No. 1 in A, Op. 13 Mintz/Bronfman DG 423 065 028942306523 01:01 Buy Now! Suppe Overture ~ Poet and Peasant Philharmonia/Boughton Nimbus 5120 083603512026 01:11 Buy Now! Gabrieli, D. Ricercar II in A minor Anner Bylsma DHM 7978 054727797828 01:22 Buy Now! Howells Rhapsody in D flat, Op. 17 No. 1 Christopher Jacobson Pentatone 5186 577 827949057762 Hoffmann, German Chamber Academy of 01:28 Buy Now! Harlequin Ballet cpo 999 606 761203960620 E.T.A. Neuss/Goritzki 02:01 Buy Now! Brahms Cello Sonata No. 2 in F, Op. 99 Harrell/Kovacevich EMI 56440 724355644022 02:29 Buy Now! Bach Prelude in E flat, BWV 552 Läubin Brass Ensemble DG 423 988 028942398825 Rimsky- 02:39 Buy Now! Suite ~ The Tale of Tsar Saltan, Op. 57 Suisse Romande Orchestra/Ansermet London 443 464 02894434642 Korsakov 02:59 Buy Now! Chopin Polonaise in A flat, Op. 53 "Heroic" Biret Naxos www.theclassicalstation.org n/a 03:08 Buy Now! Dvorak Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 Vienna Philharmonic/Kubelik Decca 289 466 994 028946699423 03:45 Buy Now! Strauss, R. -

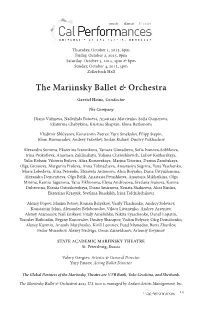

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

Link to Article

San Diego Symphony News Release www.sandiegosymphony.org Contact: April 15, 2016 Stephen Kougias Director of Public Relations 619.615.3951 [email protected] To coincide with Comic-Con, San Diego Symphony Presents: Final Symphony: The Ultimate Final Fantasy Concert Experience; Thurs July 21; 8PM The Legend of Zelda: Symphony of the Goddesses – Master Quest; Friday, July 22; 8PM Concerts to be performed at Downtown’s Jacobs Music Center – Copley Symphony Hall; tickets on sales now. Final Symphony: The Ultimate Final Fantasy Concert Experience, the concert tour featuring the music of Final Fantasy VI, VII and X will make its debut this summer stopping in San Diego on Thursday, July 21 with the San Diego Symphony performing the musical score live on stage. Following sell-out concerts and rave reviews across Europe and Japan, Final Symphony takes the celebrated music of composers Nobuo Uematsu and Masashi Hamauzu and reimagines it as a fully realized, orchestral suites including a heart-stirring piano concerto based on Final Fantasy X arranged by composer Hamauzu himself, and a full, 45-minute symphony based on the music of Final Fantasy VII. “We’ve been working hard to bring Final Symphony to the U.S. and I’m absolutely delighted that fans there will now be able to see fantastic orchestras perform truly symphonic arrangements of some of Nobuo Uematsu and Masashi Hamauzu’s most beloved themes,” said producer Thomas Böcker. “I’m very excited to see how fans here react to these unique and breathtaking performances. This is the music of Final Fantasy as you’ve never heard it before.” Also joining will be regular Final Symphony conductor Eckehard Stier and talented pianist Katharina Treutler, who previously stunned listeners with her virtuoso performance on the Final Symphony album, recorded by the world famous London Symphony Orchestra at London’s Abbey Road Studios, and released to huge critical acclaim in February 2015. -

Musical Notations 3

F.A.P. May/June 1971 Musical Notations on Stamps: Part 3 By J. Posell Since my last article on this subject which appeared in FAP Journals (Vol. 14, 4 and 5), a number of stamps have been issued with musical notation which have aroused considerable interest and curiosity. Rather than waiting the five year period which I promised our readers, I have been prevailed upon to compile a listing of these issues now. Some of the information contained here has already been sent to different collectors who made inquiries of me; some of it has already appeared in print. However, it seems appropriate to include it all under one roof again and so I beg the indulgence of my friends who may find some of this reading repetitious. AJMAN Scott ??? Michel 427 A This issue was described in detail by this writer in the Western Stamp Collector for 16 May 1970. The issue consists of four stamps and a souvenir sheet all issued both perforated and imperforate. The imperforate stamps include the musical quotation both at top and bottom plus a picture of a violin in the border at right. The notation is strangely incorrect on all issues. The following information is extracted from the above article. The music on the Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) stamp is the opening chorale from the St. Matthew Passion (Ah dearest Jesu), Bach's most famous oratorio. This is originally written in the key of B minor but on the stamp it has been transposed down to the key of G minor.