Impact Assessment in EU Lawmaking Meuwese, A.C.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2004 2009 Session document FINAL A6-0365/2005 28.11.2005 ***I REPORT on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the retention of data processed in connection with the provision of public electronic communication services and amending Directive 2002/58/EC (COM(2005)0438 – C6-0293/2005 – 2005/0182(COD)) Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Rapporteur: Alexander Nuno Alvaro RR\591654EN.doc PE 364.679v02-00 EN EN PR_COD_1am Symbols for procedures * Consultation procedure majority of the votes cast **I Cooperation procedure (first reading) majority of the votes cast **II Cooperation procedure (second reading) majority of the votes cast, to approve the common position majority of Parliament’s component Members, to reject or amend the common position *** Assent procedure majority of Parliament’s component Members except in cases covered by Articles 105, 107, 161 and 300 of the EC Treaty and Article 7 of the EU Treaty ***I Codecision procedure (first reading) majority of the votes cast ***II Codecision procedure (second reading) majority of the votes cast, to approve the common position majority of Parliament’s component Members, to reject or amend the common position ***III Codecision procedure (third reading) majority of the votes cast, to approve the joint text (The type of procedure depends on the legal basis proposed by the Commission.) Amendments to a legislative text In amendments by Parliament, amended text is highlighted in bold italics. Highlighting in normal italics is an indication for the relevant departments showing parts of the legislative text for which a correction is proposed, to assist preparation of the final text (for instance, obvious errors or omissions in a given language version). -

European Parliament: 7Th February 2017 Redistribution of Political Balance

POLICY PAPER European issues n°420 European Parliament: 7th February 2017 redistribution of political balance Charles de Marcilly François Frigot At the mid-term of the 8th legislature, the European Parliament, in office since the elections of May 2014, is implementing a traditional “distribution” of posts of responsibility. Article 19 of the internal regulation stipulates that the Chairs of the parliamentary committees, the Deputy-Chairs, as well as the questeurs, hold their mandates for a renewable 2 and a-half year period. Moreover, internal elections within the political groups have supported their Chairs, whilst we note that there has been some slight rebalancing in terms of the coordinators’ posts. Although Italian citizens draw specific attention with the two main candidates in the battle for the top post, we should note other appointments if we are to understand the careful balance between nationalities, political groups and individual experience of the European members of Parliament. A TUMULTUOUS PRESIDENTIAL provide collective impetus to potential hesitations on the part of the Member States. In spite of the victory of the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European elections, it supported Martin As a result the election of the new President of Schulz in July 2104 who stood for a second mandate as Parliament was a lively[1] affair: the EPP candidate – President of the Parliament. In all, with the support of the Antonio Tajani – and S&D Gianni Pittella were running Liberals (ADLE), Martin Schulz won 409 votes following neck and neck in the fourth round of the relative an agreement concluded by the “grand coalition” after majority of the votes cast[2]. -

Association of Accredited Lobbyists to the European Parliament

ASSOCIATION OF ACCREDITED LOBBYISTS TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT OVERVIEW OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT FORUMS AALEP Secretariat Date: October 2007 Avenue Milcamps 19 B-1030 Brussels Tel: 32 2 735 93 39 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.lobby-network.eu TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………..3 Executive Summary……………………………………………………….4-7 1. European Energy Forum (EEF)………………………………………..8-16 2. European Internet Forum (EIF)………………………………………..17-27 3. European Parliament Ceramics Forum (EPCF………………………...28-29 4. European Parliamentary Financial Services Forum (EPFSF)…………30-36 5. European Parliament Life Sciences Circle (ELSC)……………………37 6. Forum for Automobile and Society (FAS)…………………………….38-43 7. Forum for the Future of Nuclear Energy (FFNE)……………………..44 8. Forum in the European Parliament for Construction (FOCOPE)……..45-46 9. Pharmaceutical Forum…………………………………………………48-60 10.The Kangaroo Group…………………………………………………..61-70 11.Transatlantic Policy Network (TPN)…………………………………..71-79 Conclusions………………………………………………………………..80 Index of Listed Companies………………………………………………..81-90 Index of Listed MEPs……………………………………………………..91-96 Most Active MEPs participating in Business Forums…………………….97 2 INTRODUCTION Businessmen long for certainty. They long to know what the decision-makers are thinking, so they can plan ahead. They yearn to be in the loop, to have the drop on things. It is the genius of the lobbyists and the consultants to understand this need, and to satisfy it in the most imaginative way. Business forums are vehicles for forging links and maintain a dialogue with business, industrial and trade organisations. They allow the discussions of general and pre-legislative issues in a different context from lobbying contacts about specific matters. They provide an opportunity to get Members of the European Parliament and other decision-makers from the European institutions together with various business sectors. -

Appendix to Memorandum of Law on Behalf of United

APPENDIX TO MEMORANDUM OF LAW ON BEHALF OF UNITED KINGDOM AND EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARIANS AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER’S MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION LIST OF AMICI HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT OF THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND AND MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT House of Lords The Lord Ahmed The Lord Alderdice The Lord Alton of Liverpool, CB The Rt Hon the Lord Archer of Sandwell, QC PC The Lord Avebury The Lord Berkeley, OBE The Lord Bhatia, OBE The Viscount Bledisloe, QC The Baroness Bonham-Carter of Yarnbury The Rt Hon the Baroness Boothroyd, OM PC The Lord Borrie, QC The Rt Hon the Baroness Bottomley of Nettlestone, DL PC The Lord Bowness, CBE DL The Lord Brennan, QC The Lord Bridges, GCMG The Rt Hon the Lord Brittan of Spennithorne, QC DL PC The Rt Hon the Lord Brooke of Sutton Mandeville, CH PC The Viscount Brookeborough, DL The Rt Hon the Lord Browne-Wilkinson, PC The Lord Campbell of Alloway, ERD QC The Lord Cameron of Dillington The Rt Hon the Lord Cameron of Lochbroom, QC The Rt Rev and Rt Hon the Lord Carey of Clifton, PC The Lord Carlile of Berriew, QC The Baroness Chapman The Lord Chidgey The Lord Clarke of Hampstead, CBE The Lord Clement-Jones, CBE The Rt Hon the Lord Clinton-Davis, PC The Lord Cobbold, DL The Lord Corbett of Castle Vale The Rt Hon the Baroness Corston, PC The Lord Dahrendorf, KBE The Lord Dholakia, OBE DL The Lord Donoughue The Baroness D’Souza, CMG The Lord Dykes The Viscount Falkland The Baroness Falkner of Margravine The Lord Faulkner of Worcester The Rt Hon the -

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ««« « « « « 1999 « « 2004 ««« Session document FINAL A5-0332/2001 11 October 2001 REPORT on the progress achieved in the implementation of the common foreign and security policy (C5-0194/2001 – 2001/2007(INI)) Committee on Foreign Affairs, Human Rights, Common Security and Defence Policy Rapporteur: Elmar Brok RR\451563EN.doc PE 302.047 EN EN PE 302.047 2/18 RR\451563EN.doc EN CONTENTS Page PROCEDURAL PAGE ..............................................................................................................4 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION .............................................................................................5 EXPLANATORY STATEMENT............................................................................................11 RR\451563EN.doc 3/18 PE 302.047 EN PROCEDURAL PAGE At the sitting of 18 January 2001 the President of Parliament announced that the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Human Rights, Common Security and Defence Policy had been authorised to draw up an own-initiative report, pursuant to Rule 163 of the Rules of Procedure and with a view to the annual debate pursuant to Article 21 of the EU Treaty, on the progress achieved in the implementation of the common foreign and security policy). By letter of 4 May 2001 the Council forwarded to Parliament its annual report on the main aspects and basic choices of the CFSP, including the financial implications for the general budget of the European Communities; this document was submitted to Parliament pursuant to point H, paragraph 40, of the Interinstitutional Agreement of 6 May 1999 (7853/2001 – 2001/2007(INI)). At the sitting of 14 May 2001 the President of Parliament announced that she had referred this document to the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Human Rights, Common Security and Defence Policy as the committee responsible (C5-0194/2001). -

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT LIBE(2005)0620_1 COMMITTEE ON CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS Meeting Monday, 20 June 2005 from 15:00 to 18:30, Brussels Tuesday, 21 June 2005 from 9:00 to 12:30, Brussels Tuesday, 21 June 2005 from 15:00 to 18:30, Brussels PUBLISHED DRAFT AGENDA 1. Adoption of draft agenda 2. Chairperson's announcements 3. Approval of minutes of meetings of: Minutes of meeting of 16 and 17 March 2005 PE355.699 v01-00 Minutes of the meeting of 12 April 2005 PE357.660 v01-00 Monday, 20 June 2005, from 15:00 to 17:00 4. In the presence of the Luxembourg Presidency, M. Luc FRIEDEN, Minister of Justice and M. Nicolas SCHMIT, Minister delegate of Foreign Affairs and Immigration : Achievements of the Luxembourg Presidency in the area of Justice and Home Affairs Monday, 20 June 2005, from 17:00 to 18:00 5. Retention of data on public communications networks, for the purpose of combating crime, including terrorism LIBE/6/25028 570538EN - 1 - LIBE_OJ(2005)0620_1 v01-00 EN EN DT - PE353.467v01-00 DT - PE353.459v02-00 RR - PE357.618v03-00 Rapporteur: Alexander Nuno Alvaro (ALDE) - Notice to Members: Follow-up of referral back from the Plenary * 2004/0813(CNS) 08958/2004 - C6-0198/2004 Main: LIBE F - Alexander Nuno Alvaro (ALDE) PE357.618 v03-00 Opinion: ITRE A - Angelika Niebler (EPP-ED) JURI AL - Manuel Medina Ortega (PSE) PE355.785 v01-00 First exchange of views on the SIS II proposals 6. Access to the Second Generation Schengen Information System (SIS II) by the services in the Member States responsible for issuing vehicle registration certificates LIBE/6/28579 Rapporteur: Carlos Coelho (EPP-ED) ***III 2005/0104(COD) COM(2005)0237 - C6-0175/2005 Main: LIBE F - Carlos Coelho (EPP-ED) Opinion: TRAN A 7. -

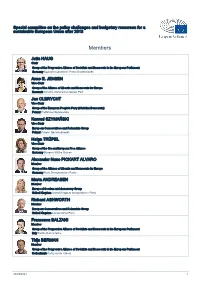

List of Members

Special committee on the policy challenges and budgetary resources for a sustainable European Union after 2013 Members Jutta HAUG Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Germany Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands Anne E. JENSEN Vice-Chair Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Denmark Venstre, Danmarks Liberale Parti Jan OLBRYCHT Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska Konrad SZYMAŃSKI Vice-Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Helga TRÜPEL Vice-Chair Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Alexander Nuno PICKART ALVARO Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Germany Freie Demokratische Partei Marta ANDREASEN Member Europe of freedom and democracy Group United Kingdom United Kingdom Independence Party Richard ASHWORTH Member European Conservatives and Reformists Group United Kingdom Conservative Party Francesca BALZANI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Thijs BERMAN Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Netherlands Partij van de Arbeid 26/09/2021 1 Reimer BÖGE Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands José BOVÉ Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance France Europe Écologie Michel DANTIN Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) France Union pour un Mouvement Populaire Jean-Luc DEHAENE Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Belgium Christen-Democratisch & Vlaams Albert DESS Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern e.V. -

Special Report

SPECIAL REPORT Key points for the 8th term of the European Parliament (2014-2019) Madrid, November 2014 BARCELONA BOGOTÁ BUENOS AIRES LIMA LISBOA MADRID MÉXICO PANAMÁ QUITO RIO J SÃO PAULO SANTIAGO STO DOMINGO KEY POINTS FOR THE 8TH TERM OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT (2014-2019) 1. THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 1. THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2. THE LATEST ELECTION The European Parliament has, since its creation in 1962 in the 3. MAIN ISSUES IN THE context of the evolution of European integration, become the LEGISLATIVE AGENDA European Union (EU) Institution to have gained more power and 4. SPANISH DELEGATION relevance in the decision-making process of the Union. Indeed, over the years, it has gained increasingly important powers, legitimized 5. CONCLUSIONS and differentiated by the fact that it is the only EU Institution to be 6. APPENDIX 1: COMPETENCES elected by universal suffrage. 7. APPENDIX 2: CURRENT COMPOSITION OF THE It has evolved from being a mere advisory body to having the COMMITTEES power to co-legislate, together with the Council, in more than 85 legislative areas, exercising legislative powers as well as powers 8. APPENDIX 3: THE CURRENT of budgetary and political control. It also wields a considerable BUREAU OF THE EUROPEAN amount of political influence, and its competences include those PARLIAMENT of electing the President of the European Commission, vetoing the 9. APPENDIX 4: EUROPEAN appointment of the College, and even forcing the resignation of the PARLIAMENT DELEGATIONS entire Commission after a motion of no confidence. AUTHORS The official headquarters of the Parliament are in Strasbourg, where the main plenary sessions are held. -

Minutes of the Sitting of 10 March 2009 (2009/C 234 E/02)

29.9.2009 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 234 E/25 Tuesday 10 March 2009 2009-2010 SESSION Sitting of 10 to 12 March 2009 STRASBOURG MINUTES OF THE SITTING OF 10 MARCH 2009 (2009/C 234 E/02) Contents Page PROCEEDINGS OF THE SITTING . 29 1. Opening of the session . 29 2. Opening of the sitting . 29 3. Debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law (announcement of motions for resolution tabled) . 29 4. Decision on urgent procedure . 30 5. Type-approval requirements for the general safety of motor vehicles ***I (debate) . 30 6. Integrated pollution prevention and control: industrial emissions, titanium dioxide industry, use of organic solvents, incineration of waste, large combustion plants ***I (debate) . 31 7. Public access to European Parliament, Council and Commission documents ***I (debate) . 31 8. Voting time . 31 8.1. EC-Armenia agreement: air services * (Rule 131) (vote) . 32 8.2. Agreement between the EC and Israel on certain aspects of air services * (Rule 131) (vote) 32 8.3. Additional protocol to the Agreement between the EC and South Africa, to take account of the accession of Bulgaria and Romania to the EU *** (Rule 131) (vote) . 32 8.4. Next steps in border management in the EU (Rule 131) (vote) . 33 8.5. Cross-border transfers of companies’ registered offices (Rule 131) (vote) . 33 8.6. Future of the European Common Asylum System (Rule 131) (vote) . 33 8.7. Commission action plan towards an integrated internal control framework (Rule 131) (vote) . 33 8.8. -

European Parliament Minutes En En

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2005 - 2006 MINUTES of the sitting of Wednesday 9 March 2005 P6_PV(2005)03-09 PROVISIONAL VERSION PE 356.319 EN EN KEYS TO SYMBOLS USED * Consultation procedure ** I Cooperation procedure: first reading ** II Cooperation procedure: second reading *** Assent procedure ***I Codecision procedure: first reading ***II Codecision procedure: second reading ***III Codecision procedure: third reading (The type of procedure is determined by the legal basis proposed by the Commission) INFORMATION RELATING TO VOTING TIME Unless stated otherwise, the rapporteurs informed the Chair in writing, before the vote, of their position on the amendments. ABBREVIATIONS USED FOR PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES AFET Committee on Foreign Affairs DEVE Committee on Development INTA Committee on International Trade BUDG Committee on Budgets CONT Committee on Budgetary Control ECON Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs EMPL Committee on Employment and Social Affairs ENVI Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety ITRE Committee on Industry, Research and Energy IMCO Committee on the Internal Market and Consumer Protection TRAN Committee on Transport and Tourism REGI Committee on Regional Development AGRI Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development PECH Committee on Fisheries CULT Committee on Culture and Education JURI Committee on Legal Affairs LIBE Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs AFCO Committee on Constitutional Affairs FEMM Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality PETI Committee on Petitions ABBREVIATIONS USED FOR POLITICAL GROUPS PPE-DE Group of the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats) and European Democrats PSE Socialist Group in the European Parliament ALDE Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Verts/ALE Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance GUE/NGL Confederal Group of the European United Left – Nordic Green Left IND/DEM Independence and Democracy Group UEN Union for Europe of the Nations Group NI Non-attached Members Contents 1. -

Official Journal C 268 E Volume 46 of the European Union 7 November 2003

ISSN 1725-2423 Official Journal C 268 E Volume 46 of the European Union 7 November 2003 English edition Information and Notices Notice No Contents Page I (Information) EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT WRITTEN QUESTIONS WITH ANSWER (2003/C 268 E/001) E-1193/02 by Erik Meijer to the Commission Subject: Consequences of introduction of the euro: measures to protect people against price increases and a decline in purchasing power ..................................................... 1 (2003/C 268 E/002) E-1906/02 by Graham Watson to the Commission Subject: ‘Settled status’ test for student loans in the UK (Supplementary answer) .................... 3 (2003/C 268 E/003) E-2407/02 by Charles Tannock to the Commission Subject: Human rights violations in Guatemala ...................................... 3 (2003/C 268 E/004) E-2415/02 by Jillian Evans to the Commission Subject: Persecution of aid workers in Guatemala ..................................... 4 Joint answer to Written Questions E-2407/02 and E-2415/02 . 4 (2003/C 268 E/005) E-2417/02 by Margrietus van den Berg to the Commission Subject: Blocking by President Robert Mugabe of international food aid to some sections of the population in Zimbabwe ........................................................... 5 (2003/C 268 E/006) E-2440/02 by Erik Meijer to the Commission Subject: Discrimination against Kurdish northern Iraq in relation to the Baghdad regime in the implementation of the UN oil-for-food programme ............................................... 5 (2003/C 268 E/007) E-2443/02 by Marco Cappato to the Commission Subject: Report by the Contraloría de la República on the Plan Colombia ....................... 7 (2003/C 268 E/008) E-2451/02 by Erik Meijer to the Commission Subject: Measures to tackle present and future increases in consumer prices as a result of the introduction of the euro ............................................................. -

The Revolving Door: Greasing the Wheels of the TTIP Lobby

Published on Corporate Europe Observatory (http://corporateeurope.org) Home > The revolving door: greasing the wheels of the TTIP lobby The prospective EU-US trade deal TTIP (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership) could be the world's biggest such treaty. While there are disagreements and divergences, in many areas of the negotiations the European Commission is singing from the corporate hymn-sheet. The revolving door between the public and private sectors is helping to grease the wheels of the TTIP corporate lobby. Some of the EU's most senior decision-makers and officials, alongside those from the member state levels, spin through the revolving door into corporate advisor roles; others go in the other direction, from corporate jobs into the public sector. These revolving door cases cover some of the biggest EU corporate lobby sectors, including telecoms and IT issues; food and agriculture; finance; investor-state dispute settlement; pharmaceuticals; regulatory cooperation; and others. This phenomenon creates great potential for conflicts of interest, and demonstrates the synergies between business interests and the European Commission, the UK government, and others when it comes to TTIP and trade negotiations. Revolving door cases featured in this report Name From To Karl De Gucht Trade Commissioner Board of Belgacom? John Clancy Spokesman to Trade Commissioner FTI Consulting Maria Trallero DG Trade European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) Tobias McKenney DG Internal Market Google Joao Pacheco DG