Rvw Journal 29.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choral Evensong the 18Th Sunday After Trinity

ST EDMUND HALL Choral Evensong The 18th Sunday after Trinity Speaker: The Revd Anthony Buckley Being oneself, changing the world 11 October 2020 6.30 pm What is Evensong? Evensong is one of the Church of England’s ancient services. It provides an open and generous space for quiet and reflection, for song and speech and prayer, as it draws from biblical readings, canticles, and the Church’s long tradition of hymns. All are welcome. Many have said, “Prayer is the key to the day and the lock to the night.” In the Anglican tradition, daily prayer is set at morning and evening for precisely this purpose: to give the opportunity to greet each new day as a divine gift and to prepare our hearts and minds for rest each night. It is founded in a sense of gratitude and wonder, and centred on the faith of Jesus Christ. We invite everyone to join in, as they are able, by listening attentively to the choir, readers, and ministers, and by saying together with us those prayers that are marked in bold: the Lord’s Prayer, the Grace, and the Amens. This year, we are meeting in many locations, not just in the Chapel. Space is primarily limited to the choir, readers, and speaker, but contact the chaplain to enquire about seating. Those who cannot join us in person may do so by Zoom at: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/87112377996?pwd=bm9zMWZreEl4M1RiK2to OXNvNW9aZz09 Please join us for drinks after the service. Speaker Our speaker this evening is the Revd Anthony Buckley, Vicar of St Michael at the North Gate. -

Robin in Context

Robin in context Introduction Robin produced some 115 compositions, among them a symphony, a violin concerto, a ballet, a masque, an opera, two oratorios, chamber music, pieces for piano and for organ, songs and choral works, both small- and large-scale. However, in addition to being the composer’s favourite and most personal genre, the songs for solo voice and piano are Robin’s largest and most condensed genre. These compositions will now be considered here within the context of early twentieth century English music and later through critical analysis. By the time Robin commenced song composition, a school of English song was well established through the work and compositions of such ‘main’ composers as Parry, Stanford, Vaughan Williams, Gurney, Warlock and Finzi. However, in the contextualisation of Robin’s songs, other aspects need to be considered in addition to the main composers of song. These include the existence of a twentieth century English musical renaissance and its main composers; Robin’s studies at the Royal College of Music; contemporary composition students at the RCM; the ‘organ loft’ song composers; the friendship with Balfour Gardiner; and the development of music publishing, the British Broadcasting Company (subsequently, Corporation), musical education in schools and amateur music-making (including the many local musical festivals throughout the country). 1 The twentieth-century English musical renaissance Howes (1966) and Hughes/Stradling (1993) suggest and have proven the existence of a twentieth century ‘English musical renaissance’. Having argued the necessity for such a phenomenon, these writers explain its development, including a revival in the music of the Tudors and Bach, and a systematic preservation of and belief in English folksong. -

Choral Evensong with Carols

THE CATHEDRAL AND METROPOLITICAL CHURCH OF CHRIST, CANTERBURY Choral Evensong with Carols Christmas Eve Thursday 24th December 2020 5.30pm Welcome to Canterbury Cathedral for this Service For your safety Please keep social distance at all times Please stay in your seat as much as possible Please use hand sanitiser on the way in and out Please avoid touching your face and touching surfaces Cover Image: The Nativity (Christopher Whall) South West Transept, Canterbury Cathedral Transept As part of our commitment to the care of the environment in our world, this Order of Service is printed on unbleached 100% recycled paper Please ensure that mobile phones are switched off. No form of visual or sound recording, or any form of photography, is permitted during Services. Thank you for your co-operation. An induction loop system for the hard of hearing is installed in the Cathedral. Hearing aid users should adjust their aid to T. Large print orders of service are available from the stewards and virgers. Please ask. Some material included in this service is copyright: © The Archbishops' Council 2000 © The Crown/Cambridge University Press: The Book of Common Prayer (1662) Hymns and songs reproduced under CCLI number: 1031280 Produced by the Music & Liturgy Department: [email protected] 01227 865281 www.canterbury-cathedral.org ORDER OF SERVICE All stand as the choir and clergy enter the Nave Welcome The Dean Please remain standing Introit O little one sweet, O little one sweet, O little one mild, O little one mild, thy Father’s purpose thou hast fulfilled; with joy thou hast the whole world filled; thou cam’st from heav’n to mortal ken thou camest here from heaven’s domain equal to be with us poor men, to bring men comfort in their pain, O little one sweet, O little one sweet, O little one mild. -

CHORAL EVENSONG World Without End

Then shall the earth bring forth her increase: and God, even our own God, shall give us his blessing. God shall bless us: and all the ends of the world shall fear him. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son: and to the Holy Ghost; As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be: CHORAL EVENSONG world without end. Amen. Tuesday 29 May 2018 The FIRST LESSON is read Exodus 2: 11–end (NRSV p. 47) Welcome to this service of Choral Evensong All stand for the MAGNIFICAT sung by The Choir of Trinity College Cambridge Tonus peregrinus Plainsong Please ensure that all electronic devices, My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced including cameras, are switched off in God my Saviour. For he hath regarded the lowliness of his handmaiden. For behold, from henceforth all generations VOLUNTARY shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath magnified me: and holy is his Name. And his mercy is on them that Flûtes, Op. 91/4 Langlais fear him throughout all generations. He hath shewed strength with his arm; he hath scattered the proud in the INTROIT sung from the Ante-Chapel imagination of their hearts. He hath put down the mighty Benedicta sit from their seat, and hath exalted the humble and meek. Blessed be the Holy Trinity and the undivided Unity: He hath filled the hungry with good things; and the rich we will praise and glorify him, because he hath showed he hath sent empty away. He remembering his mercy hath his mercy upon us. -

Sibelius Society

UNITED KINGDOM SIBELIUS SOCIETY www.sibeliussociety.info NEWSLETTER No. 84 ISSN 1-473-4206 United Kingdom Sibelius Society Newsletter - Issue 84 (January 2019) - CONTENTS - Page 1. Editorial ........................................................................................... 4 2. An Honour for our President by S H P Steadman ..................... 5 3. The Music of What isby Angela Burton ...................................... 7 4. The Seventh Symphonyby Edward Clark ................................... 11 5. Two forthcoming Society concerts by Edward Clark ............... 12 6. Delights and Revelations from Maestro Records by Edward Clark ............................................................................ 13 7. Music You Might Like by Simon Coombs .................................... 20 8. Desert Island Sibelius by Peter Frankland .................................. 25 9. Eugene Ormandy by David Lowe ................................................. 34 10. The Third Symphony and an enduring friendship by Edward Clark ............................................................................. 38 11. Interesting Sibelians on Record by Edward Clark ...................... 42 12. Concert Reviews ............................................................................. 47 13. The Power and the Gloryby Edward Clark ................................ 47 14. A debut Concert by Edward Clark ............................................... 51 15. Music from WW1 by Edward Clark ............................................ 53 16. A -

Spring 2018/2 by Brian Wilson and Dan Morgan

Second Thoughts and Short Reviews - Spring 2018/2 By Brian Wilson and Dan Morgan Reviews are by Brian Wilson unless signed [DM]. Spring 2018/1 is here. Links there to earlier editions. Index: ADAMS Absolute Jest; Naïve and Sentimental Music_Chandos BACH Keyboard Music: Volume 2_Nimbus - Complete Organ Works Volume 7_Signum BEETHOVEN Triple Concerto_DG (+ BRAHMS) BORENSTEIN Violin Concerto, etc._Chandos BRAHMS Double Concerto_DG (+ BEETHOVEN) BRUCKNER Symphony No. 3_Profil - Symphony No. 4 in E-flat ‘Romantic’_LSO Live BUSONI Orchestral Works_Chandos ELGAR Violin Sonata, etc._Naxos_Chandos GERSHWIN Rhapsody in Blue_Beulah GUILMANT Organ Works_Chandos (+ WIDOR, FRANCK, SAINT-SAËNS) IRELAND Downland Suite, etc._Chandos - Mai Dun, Overlanders Suite, etc._Hallé JANITSCH Rediscoveries from the Sara Levy Collection_Chandos KARAYEV Symphony No.1; Violin Concerto_Naxos - Seven Beauties Suite, etc._Chandos LIDSTRÖM Rigoletto Fantasy_BIS (+ SHOSTAKOVICH Cello Concerto) LISZT A Faust Symphony_Alpha LUDFORD Missa Videte miraculum, etc._Hyperion MAHLER Symphony No.1_CAvi - Symphonies Nos. 4-6_Signum - Symphony No. 6_BIS MONTEVERDI Lettera Amorosa_Ricercar - Clorinda e Tancredi: Love scenes_Glossa - Night - Stories of Lovers and Warriors_Naïve PALUMBO Three Concertos_BIS RACHMANINOV The Bells, Symphonic Dances_BRKlassik ROSSINI Overtures – Gazza Ladra, Guillaume Tell_Beulah SAUER Piano Concerto No.1_Hyperion (+ SCHARWENKA) SCHARWENKA Piano Concerto No.4_Hyperion (+ SAUER) SHOSTAKOVICH Cello Concerto No.1_BIS (+ LIDSTRÖM) TALLIS Lamentations and Medieval Chant_Signum TIPPETT Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2_Hyperion VIVALDI Concertos Op.8/1-12_Chandos - Double Concertos_Chandos WESLEY, Samuel Symphonies_Chandos WESLEY, Samuel Sebastian Ascribe unto the Lord - Sacred choral works_Chandos WIDOR Organ Works_Chandos (see GUILMANT) Electric Django (Reinhardt)_Beulah *** MusicWeb International April 2018 Second Thoughts and Short Reviews - Spring 2018/2 Nicholas LUDFORD (c.1490-1557) Ninefold Kyrie (at Ladymass on Tuesday, Feria iii) [4:45] Alleluia. -

16-12 Prog.Pdf

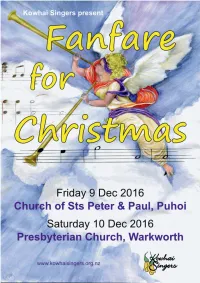

Fanfare for Christmas The title of our concert is taken from our opening song for the full choir - Fanfare for Christmas Day: Gloria in Excelsis Deo, an anthem, by Martin Shaw. Martin Edward Fallas Shaw OBE FRCM (1875 – 1958) was an English composer, conductor and (in his early life) theatre producer. His over 300 published works include songs, hymns, carols, oratorios, several instrumental works, a congregational mass setting (the Anglican Folk Mass) and four operas including a ballad opera With a voice of Singing is another of his anthems in our repertoire, performed several times in the past at Kowhai Singers concerts. Conductor Peter Cammell (BA, Post Grad. Dip. Mus.) studied music at Auckland and Otago Universities and then taught in secondary schools in both Auckland and London. He has sung in the Dorian Choir, Auckland Anglican Cathedral Choir, Cantus Firmus, The Graduate Choir, Musica Sacra, Viva Voce, and is currently with Calico Jam. As director of the Kowhai Singers for 21 years Peter has worked hard to extend the choir's repertoire and singing skills and thereby their musical understanding. Accompanist Riette Ferreira (PhD) has been the choir's pianist for most of the time since August 2003 except when personal commitments such as study towards her PhD degree in Music has taken her away from us. She has wide experience teaching music in both South African and New Zealand schools and is frequently engaged as director and/or keyboard player for musical theatre productions at Centrestage Theatre, Orewa. Introit - Beata Viscera Marie Virginis† (words 12th C) Pontin Fanfare for Christmas Day: Gloria in Excelsis Deo Martin Shaw While shepherds watched their flocks (with the congregation) Welcome, Yule! (Anon. -

Bristol Waste's First Ever Reuse Shop Opens

Your local community newspaper with news and views from the Shirehampton area Poppies No. 586 - November 2020 www.shire.org.uk 5,000 copies monthly on the Green Shire See Pages 2 & 12 Have you got a job that needs doing? Go to YOUR LOCAL EXPERTS section on pages 16-18 to find a local business who can help. BOPF Community Fund Bids TRASH TO TREASURE: See Page 6 Bristol Waste’s First Ever Reuse Shop Opens In June 2020, Avonmouth Reuse and Recycling Centre opened a shop for items which would otherwise be going to waste. These items include low cost goods, such as CDs, vinyl records, books and toys, but also TVs, furniture and a large selection of tiles and paint. Any income generated is used to fund further reuse work by the Company and a percentage donated to local charities. This spacious new building is situated alongside the Recycling Centre with its own entrance. There is no need to queue on the road with those wanting to use the Recycling Centre only, nor to adhere to the ODD or EVEN rule; simply inform a staff member at the gate that you want to visit the shop only and he/she will direct you straight there and show you where to park. The shop hours are from 10am to 3pm on Monday to Friday and the telephone number is 0117 304 9590. The shop is well set up to cater for its visitors, with delightful staff, Manager Joanna Dainton, Assistant Callum Stilwell and Volunteer Juliet Le Fevre on hand. -

Sunday 1 November 2020 Choral Evensong All Saints Day Online Evensong from University College, Oxford

Sunday 1 November 2020 Choral Evensong All Saints Day Online Evensong from University College, Oxford A warm welcome to our service this week. Thank you for joining us from wherever you may be. The full text of the service is found in this pdf file that you have downloaded from our Online Evensong page. An audio-recording of the full service is on the page where you found the link to this text. Our preacher this week is the Rt Revd Christopher Chessun, the Bishop of Southwark. 1 WORDS OF WELCOME INTROIT ‘With prayer and supplication’ With prayer and supplication, let your requests be known unto God. And the peace of God which passeth all understanding, shall keep your hearts and minds, through Jesus Christ, our Lord. Words: Philippians 4.6-7 Music: Amy Beach (1867-1944) 2 HYMN ‘Jerusalem the Golden’ Jerusalem the golden, with milk and honey blest, beneath thy contemplation sink heart and voice oppressed. I know not, O I know not, what social joys are there; what radiancy of glory, what light beyond compare. They stand, those halls of Zion, conjubilant with song, and bright with many an angel, and all the martyr throng. The Prince is ever in them, the daylight is serene; the pastures of the blessed are decked in glorious sheen. There is the throne of David; and there, from care released, the song of them that triumph, the shout of them that feast; and they who, with their Leader, have conquered in the fight, forever and forever are clad in robes of white. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Seventh Sunday After Pentecost

Seventh Sunday after Pentecost Holy Eucharist July 11th, 2021 10:00AM Service The Gathering Organ Voluntary Ceremonial Suite for Organ, No 2, Aria Music: Carson Cooman (b. 1982 ) Welcome Abel E. Lopez, Rector Prayer of Meditation The Rev. Jim Lee Imaginative God, creator of all that is, inspire us who are overwhelmed by the complexities of life. Send through us the great rushing wind of your spirit to stir our hopes and breathe into us new life. Rekindle in us the flame of your spirit, that with energy and enthusiasm we may rise to meet the challenges of our life, and work to bring heaven on earth, today and every day of our lives. Amen. All stand and sing, as able. Hymn in Procession The Hymnal 1982 #365 Come, Thou Almighty King Opening Acclamation Abel E. Lopez, Rector Priest Blessed be God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. People And blessed be God’s kingdom, now and for ever. Amen. Remain standing. Collect for Purity All together. Almighty God, to you all hearts are open, all desires known, and from you no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of your Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love you, and worthily magnify your holy Name; through Christ our Lord. Amen. 2 All sing, remain standing, as able. Song of Praise The Hymnal 1982 #S-236 (found in very front of hymnal) Glory to you, Lord God of our fathers; you are worthy of praise; glory to you. Glory to you for the radiance of your holy Name; we will praise you and highly exalt you for ever. -

Come, Thou Holy Spirit Anthem for Whitsuntide by Alan Gray VOCAL / ORGAN SCORE 2

1 Come, thou holy spirit Anthem for Whitsuntide By Alan Gray VOCAL / ORGAN SCORE 2 This score is in the Public Domain and has No Copyright under United States law. Anyone is welcome to make use of it for any purpose. Decorative images on this score are also in the Public Domain and have No Copyright under United States law. No determination was made as to the copyright status of these materials under the copyright laws of other countries. They may not be in the Public Domain under the laws of other countries. EHMS makes no warranties about the materials and cannot guarantee the accuracy of this Rights Statement. You may need to obtain other permissions for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy or moral rights may limit how you may use the material. You are responsible for your own use. http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-US/1.0/ Text written for this score, including project information and descriptions of individual works does have a new copyright, but is shared for public reuse under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0 International) license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Cover Image: “Pentecostés” by Juan Bautista Mayno, 1615/1620 (Museo del Prado) 3 The “renaissance” in English music is generally agreed to have started in the late Victorian period, beginning roughly in 1880. Public demand for major works in support of the annual choral festivals held throughout England at that time was considerable which led to the creation of many large scale works for orchestra with soloists and chorus.